Minerva Cuevas: The Construction of Reality

La construcción de la realidad

Carmen Cebreros Urzaiz

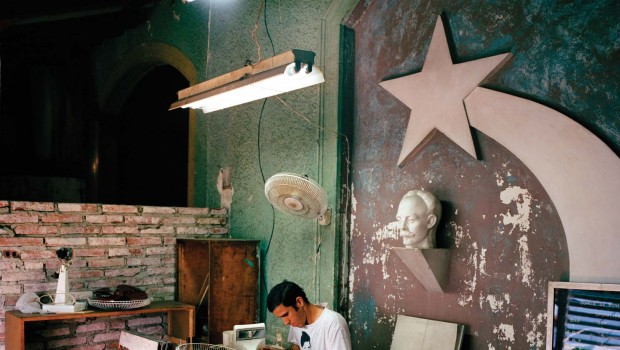

Minerva Cuevas thoroughly exemplifies what it means to be a “citizen of the world” in the contemporary moment. Constantly on the move from city to city, her work processes arise out of temporary residencies in specific locations, during which she delves into collective histories, marginalized or hidden by official narratives. Her practice is born out of two fundamental lines of questioning: the first has to do with the mechanisms for the distribution of images and their epistemological function; the second with the configurations—both collective and organic—of community in the broadest sense. This goes beyond mere geographic coincidence and even transcends it; in addition, the forms of representation she selects play a fundamental role. Communities of animals constantly appear in the work of this artist as allegories for models of connection in human societies.

Her first experimental interventions began with the project Mejor Vida Corp. (Better Life Corp.), starting in 1999 in Mexico City; an ironic simulacrum of a corporation which offered services—anti-profit and quite generously—that consisted of an array of products to endure the dynamics of life imposed by capitalism, especially for those without any capital: student photo ID’s to get discounts in movie theaters and museums, letters of recommendation for jobs with the name of the corporation to whomever requests one, bar codes to replace the labels at grocery stores to get discounts on food, metro tickets handed out at rush hours. With all services, it is always very clear, of course, that the corporation is the one offering the services and thus ensures their “market presence.”

Minerva Cuevas’ work questions the role images play in the construction of reality…

Cuevas grounds her work in this logic, uncovered through her research on different North American agricultural corporations operating in Latin America—whose history of imposing exploitation and consumption in several of these countries has been kept more or less hidden. Cuevas begins to co-opt the logos, labels and publicity posters from important multinational companies’ products, using their potential for expedited communication and conserving their recognizable elements, although she does minimally modify their contents. In this way, she is able to synthesize and use disguises in order to make clear a series of historical events that have favored the expansion of these corporations, but which would never be mentioned in a media campaign. An example of this work can be found in the mural Del Montte, 2003, which refers to the United States involvement in the coup against Guatemalan president Jacobo Árbenz. It also references the relationship between several North American politicians and the United Fruit Company which was able to establish a monopoly on bananas—just to mention one such monopoly—in several Central American countries, thanks to CIA participation. Terra Primitiva, a mural presented at the Sao Paulo biennial in 2006, describes an episode in the fierce struggle of companies like Cargill and Monsanto to acquire the patents to vernacular species developed in the Amazon.

In addition, Cuevas attempts to highlight the affinities between different collectivities that go unnoticed and invest them with a sense of community by means of exercises calling for these linkages to be recognized. Concierto para Lavapiés (Concert for Lavapiés), 2003, is the result of a newspaper ad directed at street musicians interested in participating in a spontaneous jam/concert in the Lavapiés neighborhood in Madrid; its population is presumably fifty percent immigrant. Although at first it was scheduled to last thirty minutes, the influx of musicians and the enthusiasm unleashed caused it to go on for more than an hour. The event was documented in a series of photographs and a video. Her most recent intervention consisted of putting a coin into circulation— S·COOP, 2009—among the merchants of Petticoat Lane in East London. This currency is only accepted at Monochrome, an ice cream shop and temporary documentation center exhibiting the history of the neighborhood, which was a center of textile production and where an immigrant population—first Jews, then Bengalis—has lived and worked.

The exhibition Phenomena, presented in 2007, took its name from the Kantian distinction between the realm of appearances, reality filtered by human perception and affected by point of observation (phenomena), and the realm of things in and of themselves, the real-real, what is knowable only through reason (noumena). The artist projects a series of film fragments onto the walls of the exhibition halls; this footage is from scientific experiments from the beginning of the Twentieth Century, as well as several slides of animals in captivity and in the process of being domesticated. A series of microscopes in the same area also function as projectors, showing lenses whose amplified images seem to have emerged from a kaleidoscope. The antiquated slides of these images seem to be an attempt to return to us to that other “point of view,” and from that different vantage point (phenomena) sketch out a notion of time.

The fundamentals of contemporary science have their origin in observations of daily transformations. Several of Minerva Cuevas’ works enact a kind of homage to those perservering observers who tried to anticipate natural phenomena in order to document them. People like the Swiss biologist Moisés Bertoni who went to the Paraná and decided to stay there to study its species for the rest of his life, or Stanislav Lem, a doctor and an academic who left a record of his concerns about the possibility of communication with another kind of civilization in several futurist and philosophical novels and stories, Solaris being the most well known.

Minerva Cuevas’ work questions the role images play in the construction of reality and her objective is to return us to a moment before the image when experience and observation could still be differentiated. And in the midst of the accelerated development of technologies designed to dominate and invent certain sections of the world at the cost of the others, and in which knowledge is a mere instrument for these ends, this artist transports us to those destinations where the act of doing science— and I would say also the act of doing art—is an attempt to understand the world in order find a better way to inhabit it.

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

Minerva Cuevas ejemplifica cabalmente lo que la “ciudadanía del mundo” significa en tiempos actuales. Moviéndose constantemente de ciudad en ciudad, sus procesos de trabajo surgen a partir de estancias temporales en una determinada localidad, durante las cuales indaga en las historias colectivas, descartadas o escondidas por las narrativas ofi ciales. Su práctica deriva de dos interrogaciones fundamentales: la primera sobre los mecanismos de distribución de las imágenes y su función epistemológica; la segunda, sobre las configuraciones —desde lo colectivo y orgánico— de comunidad en un amplio sentido, que rebasa la mera coincidencia geográfica e incluso la trasciende, y donde además las formas de representación juegan un rol fundamental. Constantemente las comunidades animales fungen en el trabajo de esta artista como alegorías de modelos de vínculo para las sociedades humanas.

Sus primeros experimentos de inserción se remontan al proyecto Mejor Vida Corp., iniciado en 1999 en la Ciudad de México; un irónico simulacro de corporación, cuya oferta de servicios —antilucrativa y más bien desprendida— consiste en una gama de productos para sobrellevar las dinámicas impuestas por el capitalismo, especialmente para quienes no cuentan con capital: credenciales de estudiante con fotografía para obtener descuentos en cines y museos, cartas de recomendación laboral expedidas a nombre de la corporación a quien sea que las solicite, códigos de barras para reemplazar las etiquetas de los supermercados y conseguir descuentos en alimentos, boletos de metro repartidos en horas pico; dejando siempre claro, eso sí, que es la corporación quien ofrece los servicios y asegurándose —así— su “presencia de mercado”.

Varias obras de Mineva Cuevas rinden homenaje a aquellos observadores que intentaron anticipar los fenómenos naturales para aprovecharlos.

Basándose en esta lógica, y a raíz de sus investigaciones sobre diversas corporaciones agrícolas norteamericanas operando en Latinoamérica —cuyo historial de imposición de modos de explotación y consumo en varios de estos países se mantiene más o menos oculto—, Cuevas empieza a parasitar los logotipos, etiquetas o carteles publicitarios de productos de importantes compañías multinacionales, utilizando su potencial de comunicación expedita, manteniendo los elementos reconocibles, aunque modifi cando mínimamente su contenido. Así consigue sintetizar y camuflar para hacer evidentes una serie de acontecimientos históricos que han propiciado la expansión de estas corporaciones, pero que jamás serían declarados en ninguna campaña de medios. Ejemplo de este trabajo puede encontrarse en el mural Del Montte, 2003, que hace referencia a la intervención de Estados Unidos en el golpe de estado al presidente guatemalteco Jacobo Árbenz y la relación de varios políticos norteamericanos con la empresa United Fruit Company que ha logrado establecer un monopolio platanero —por mencionar sólo uno— en varios países centroamericanos, gracias a la participación de la CIA. Terra Primitiva, un mural presentado en la bienal de Sao Paulo en 2006, describe un episodio en la voraz lucha de empresas como Cargill y Monsanto por adquirir las patentes de especies vernáculas desarrolladas particularmente en el Amazonas.

Cuevas además intenta destacar las afi nidades que pasan desapercibidas entre ciertas colectividades, y dotarlas de un sentido de comunidad a través de ejercicios que convocan a su reconocimiento. Concierto para Lavapiés, 2003, es el resultado de un anuncio en el periódico dirigido a músicos callejeros interesados en participar en un jam/concierto espontáneo en el barrio de Lavapiés en Madrid, cuya población se compone por inmigrantes presumiblemente en un cincuenta por ciento. Aunque al inicio estaba programado para durar treinta minutos, la afluencia de músicos y el entusiasmo que desencadenó, provocó que se extendiera por más de una hora; el acontecimiento queda documentado en una serie fotográfi ca y en un video. Su más reciente intervención consistió en poner en circulación una moneda —S·COOP, 2009— entre los comerciantes del mercado de Petticoat Lane al este de Londres. Dicho circulante fue útil exclusivamente en Monochrome, una nevería y centro de documentación temporal que exhibe la historia de este barrio, que fuese centro de producción textil donde habitaba y laboraba una población de inmigrantes —primero judíos, después bengalíes.

La exposición Phenomena, presentada en 2007, toma su nombre de la distinción kantiana entre el reino de las apariencias, la realidad filtrada por la percepción humana y afectada por el punto de observación (phenomena), y el reino de las cosas en sí mismas, lo realreal, lo cognoscible sólo a través de la razón (noumena).

Aquí una serie de fragmentos fílmicos de experimentos científicos de principios del siglo XX, así como varias diapositivas de animales en cautiverio y en proceso de domesticación son proyectadas sobre las superficies de la salas de exposición, donde también una serie de microscopios funcionan como proyectores, mostrando objetivos cuya imagen amplificada parece proceder de un caleidoscopio. Los dispositivos en desuso utilizados para defi nir estas imágenes parecieran tratar de devolvernos ese “punto de vista”, y desde ahí, desde nuestra mirada afectada (phenomena) esbozar una noción del tiempo.

Los fundamentos de la ciencia contemporánea tienen su origen en las observaciones de las transformaciones cotidianas. Varias obras de Minerva Cuevas rinden una suerte de homenaje a aquellos perseverantes observadores que intentaron anticipar los fenómenos naturales para aprovecharlos. Personajes como el biólogo suizo Moisés Bertoni que conoció el Paraná y decidió quedarse a estudiar sus especies el resto de su vida, o Stanislav Lem, médico y académico que dejó registro de sus inquietudes sobre la posibilidad de comunicación con otro tipo de civilizaciones en varias novelas y relatos futuristas y filosóficos, siendo Solaris la más conocida.

El trabajo de Minerva Cuevas se pregunta por el papel que tienen las imágenes en la construcción de realidad, y se propone llevarnos a un momento anterior donde imagen, mirada y experiencia aún podían diferenciarse. Y en medio del desarrollo acelerado de tecnologías planeadas para dominar e inventar ciertas fracciones de mundo a costa de las demás, y donde el conocimiento es un mero instrumento para tales fines, esta artista nos traslada a esos parajes donde el hacer ciencia —y diría que también hacer arte—persigue comprender el mundo para habitarlo de una mejor manera.