Populism, Freedom, Democracy and Iran

Populismo, libertad, democracia e Irán

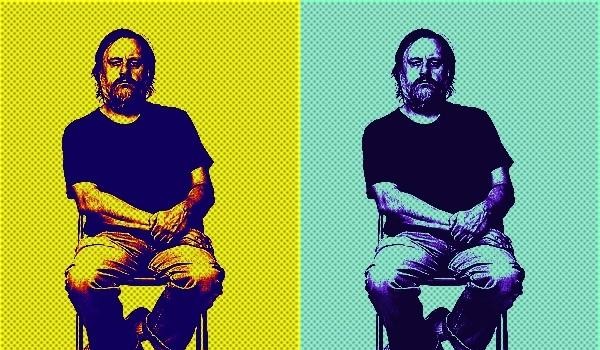

Slavoj Zizek

Populism

I would like to begin with a theoretical yet obscene point. I consider this to be a wonderful anecdote because it tells how democracy works: During a crucial battle between Prussian and Austrian armies in the XIX Century, the Prussian king was worriedly observing the battle as he didn’t know who was winning. At his side was the mastermind of the battle, a General who was a great strategist. Gazing at what appeared to be a total confusion on the battlefield, he turned to the king and said: “May I be the first to congratulate His majesty for a brilliant victory.” This is the gap between masters dignified and knowledge. The king was the master and formal commander, totally ignorant of the significance of what happened at the battlefield. The victory was for the mastermind General who helped and congratulated the king on behalf of whom he was acting. This idea of not knowing how brilliant one can be until someone else has to inform you of your geniality, is the same metaphor as if we replaced the king with people. This is exactly how democracy works. We, the people, are informed in the elections that we won a brilliant victory.

With this example, I do not mean to denigrate the people, on the contrary. I don’t buy the standard liberal critic. My problem is that I believe that truth does not lie in the extremes. In order to be authentic, I do not need to go to the extremes. When I was young, going to an extreme had the underlying idea that it had something authentic in it. I don’t accept that. I’m almost on the side of ordinary people.

Now, you can say that the problem with people is populism, and yes, I agree for reasons that I won’t discuss here. I still don’t agree with Ernesto Laclau; I’m more convinced that populism needs to be carefully reflected upon. I’m trying to prove that from democracy to populism something more is needed. An this is where the problem lies in the beautiful train of thought of Laclau’s reasoning. Do you see how in his books he counts Tito and Mao Tze Tung as populists? Well I simply trust my spontaneous intuitive notion that if they are populists, then the notion is misused. I claim that it is a crucial part of populism, to put it in Ernesto’s own terms, to mystify and displace antagonisms. His reaction would be to say that antagonisms are displayed, and that there are no authentic antagonisms. I think we can still show antagonism, but not in the sense of class struggle. Antagonism and populism, as I try to develop in defense of Laclau, are mystified in a formal way, and in order to be populist, using Ernesto’s own terms, one must recognize that people do exist and that they are a threat from the outside. That’s the zero level of populism. To put it in old Marxist terms, there are radical antagonisms that are constitutive of communities. The minimum tenet of populism is that there must be a minimal amount of order, and some external intruder (it can be imperialism, communism). The cause comes from the outside destroying the organic order. In other words, I claim that populism is always sustained by a kind of frustrated despair. I do not know what is going on, but it must stop. Populism believes in the insuring conviction that there must be somebody responsible for all the mess which is why an agent behind the scenes is needed . In this refusal to know resides the proper fetishist that names no populism. Although, at the purely formal level, fetishism involves a gesture of transference upon the subject of the fetish, it functions as an exact inversion of the standard formula of transference with the subject it is supposed to know. What fetish gives body to is precisely my refusal to subjectively assume what I know. So you see my point? I don’t think people are stupid, or with a minimal amount of will, but they voluntarily choose stupidity. Behind populism there’s always a minimum of I don’t want to know. Even if it’s not acknowledged, it is implicit. In Nietzschean terms, populism is reactive strategy.

Freedom

The refusal to know confronts us with the deadlock of our, as we put it, society of choice. There are multiple ideological investments in the topic of choice. As you probably know, brain scientists point out that freedom of choice is an illusion. We experience ourselves as free when we are able to act the way our organism determines us to act. This is the soft cognition of the redefinition of freedom. It doesn’t deny freedom, it just says freedom is not what you think it is. Freedom simply means you’re still determined by your own immanent nature when no obstacles prevent you to realize what you spontaneously want. However, Benjamin Libet defends human freedom. The zero level of freedom is not used to choose but to block or say no to your decision.

Liberal economists emphasize freedom of choice as the key ingredient of marketing economy. By buying things, we are in a way continuously voting with our mind. Deeper existential thinkers, like to deploy variations on the theme of the authentic existential choice, where the very core of our being is at stake; a choice which involves a full existential engagement opposed to the superficial choices of these or those commodities.

In the Marxist version of this theme, the multiplicity of choices the market bombards us with obfuscates the absence of real radical choices concerning the fundamental structure of our society. That is the standard Marxist criticism, you can choose Coke over Pepsi and so on, but you cannot make a more radical choice. There is however, a feature that is, I think, all too often missed: the injunction to choose when we let even the basic cognitive coordinates to make a choice. Leonardo Padura (the Cuban writer and author of Havana tetralogy) wrote in one of his novels “It is horrific not to know the past and yet be able to impact the future”. So being compelled to make decisions in a situation that remains opaque is our basic condition. In the standard choice of the first situation, the only thing left for us to do is the empty gesture of pretending to accomplish freely what knowledge the expert imposes. But, what if the choice is really free and it is for this very reason that experience is all the more frustrating? We thus find ourselves in the position of having constantly to decide on matters that will fundamentally affect our lives, but are lacking a proper foundation in knowledge. To quote John Gray, “we have been thrown into a time in which everything is provisionary. New technologies alter our lives daily. The traditions of the past cannot be retrieved. At the same time, we have little idea what the future will bring. We are forced to live as if we were free.”

This pressure to choose involves not only the ignorance about the object of choice. We are bombarded by calls to choose without being qualified to actually make the appropriate choice. Even worse, we are showered by the impossibility to answer the question of desire. When Lacan defines the object of desire as lost, his point is not simply that we never know what we desire and are condemned to the eternal search for the true object, Lacan’s point is a much more radical one. The lost object is ultimately the subject itself. The subject as an object implies that the question of desire, its original enigma, is not primarily “what do I want”, but “what do others want from me”, “what object do they see in me?” Which is why, apropos to the hysterical question “why am I that name?” “Why am I what you say that I am?” Lacan points out that the subject as such is hysterical. Lacan defines the subject as that which is not an object. The point being that the impossibility to identify yourself as an object, to know what you are for others, is constitutive of the subject. In this way, Lacan generates the entire diversity of pathological subjective positions, reading this diversity as the diversity of the answers to the hysterical question. The psychotic knows itself as the object of the other’s enjoyment, while the pervert deposits itself as the instrument of the other’s enjoyment and so on and so forth. This is why I claim there is a terrorist dimension in the pressure to choose. This terror resonates, for me at least, even in the most innocent inquiry, for example, when one reserves a hotel room. Soft or hard pillows, double or twin bed and so on… Beneath this simple questioning there is a much more radical probing, “Tell me who you are, what kind of an object do you want to be? What would fill in the depth of your desire?” This is why I think Michel Foucault’s, anti-essentialist apprehension about fixed identities, the incessant urge to practice the care of the self, to continuously re-invent, re-create oneself finds a strange echo in the dynamics of post-modern capitalism. It was, of course already the good old existentialism that claimed that a man is what he makes of himself, and existentialism linked this radical freedom to existential anxiety. But for existentialism, the anxiety of experiencing one’s freedom, the lack of one’s substantial determination, was the authentic moment when the subject saw its integration into the fixity of the given ideological universe. What existentialism wasn’t able to envisage was what Adorno tried to encapsulate with the title of his attack on Heidegger’s jargon of authenticity. How, no longer repressing it, hegemonic ideology directly mobilizes the lack of fixed identity to sustain the endless process of consumerist self-recreation. So again, to go to this eternal, already boring debate with Judy Butler, the question is not that I don’t agree with it, but I think that, precisely this eternally dynamic, nomadic self-questioning which always sustains this ambiguous anxiety “are you ready to admit who you are?”, this is the level at which consumerism makes you guilty. Not in the simple sense of “you never get the full enjoyment that you want from the commodity” however you are always supposed to freely choose what you really want, but of course, you never can.

Democracy

Consumerism in a way always makes you look non-authentic. And against this background of the difficulty of choice, populism and such, I want to approach the question of democracy. There is a distinction between two types, or rather, levels of corruption in democracy: The defacto empirical corruption and the corruption that pertains to the very form of democracy, which is the reduction of politics to the negotiation of private interests. This gap becomes visible in the rare, true cases of an honest democratic politician who while fighting empirical corruption nonetheless sustains the formal state of corruption.

In Walter Benjamin’s terms of the distinction between constituted and constituent violence, one could say that we are dealing here with the distinction between the constituted corruption (braking the laws, etc ) or rather, constitutive corruption of the very democratic form of government . The electoral democracy is only representative insofar as it is first the consensual representation of capitalism which is today the market economy. I think one needs to take this line in the strict transcendental sense. The empirical level, of course, is how the multi-party liberal democracy represents and mirrors the quantitative and disperse opinions of the people, what they think about the candidates, and so on. However, prior to this empirical level, in a much more radical sense, the multi-party democracy represents a certain vision of society, politics and the role of the individual in it. The multi-party democracy represents a precise vision of social life in which politics is organized into parties that compete through elections to exert control over the state legislative and executive apparatus. One must be aware that this transcendental frame of democracy is never neutral. It privileges certain values and practices. This non-neutrality becomes palpable in the moment of crisis when we experience the inability of the democratic system to register what people effectively want or think. I remember the UK elections of 2005. In spite of the growing personal dislike of Tony Blair –he was voted the most unpopular person in the UK. Something was very wrong. It was not that the people didn’t know what they wanted, but rather, it was their cynical resignation what prevented them to act upon. So the result was the weird gap between what people thought and how they voted. In this criticism the Jacobine privileging of virtue is discernible. In democracy there is not place for virtue. My conclusion is that it might be an animosity towards voting, suggesting there is no authenticity about it. There’s no reason to despise democratic elections, the point is only to insist that they are not in themselves apriori capable of truth. As a rule, they tend to reflect a predominant doxa determined by the hegemony ideology.

Iran

My claim is that this is exactly what is going on in Iran. Why? First, let’s look at this kind of event. Even when an oppressive force doesn’t lose power, at some point, there’s kind of psychological break when everybody knows it’s over. Richard Kapuchinski´s book tries to isolate this moment and claims to have found it. Three or four months before the Shah left the country, there were, in some suburbs of Teheran, demonstrations. People gathered at an intersection when a police approached them and shouted at them. A man looked at the officer and did nothing. The policeman shouted again, but the guy kept staring at him. The embarrassed police officer then turned around and left. The mystery is how, within a couple of hours, did all of Teheran know? It was a kind of mystical subversion. People kept dying but from that point, everyone, even the ones in power, knew the game was over. To me, this time of transition is the most interesting moment. I would describe the history of the decomposition of socialism in these terms. When did people know exactly communism was really over? Something similar happened after the second night after Iranian elections. It’s like falling in love: you don’t decide to fall in love; you just know you are in love. People discovered that they were not afraid. The police can beat them to death, but they keep going in hundreds and thousands. The way it happens is terrifying in a good sense, this sublime power of the people. Much more threatening than shouting is silence: Literally, hundreds and thousands just silently walking on the streets. Then they climb to the rooftops, almost as a ritual, and yell Alla wa akbar, God is great! And this is a crucial dogma- Why? Because combined with the color green, the color of Islam, it proves people are no longer afraid. This is something that Western commentators miss systematically, and if they acknowledge it, they assign it a secondary role. Here comes my first important point, this Mousavi is not the liberal, pro-western candidate that the media claims him to be. According to the media, there are two basic groups in Iran: the poor, primitive, Islamic-farmer majority that is manipulated by clerics, and the educated, secular, pro-Western middle class who just want the democracy experienced after the Shah. The other candidate, Mehdi Karroubi, is the Western candidate who wanted to play out some identity politics saying “we have women, we have Kurds, we have gays etc., support me and your identity will be recognized”. What Mousavi is doing is completely different to that. His mission is to return to the origins, to repeat the ‘79 revolution. I like the idea that he has the Khomeini authority behind him, and that Mousavi is not an incompetent idiot-architect, because he is an architect by profession. During the entire Iran-Iraq war, he was the prime minister and had organized a working economy at the time. His current idea is go back to the ‘79 roots. His slogans say he is nothing and that the people will organize themselves. With all ironic criticism set aside, I have accepted the line that the ‘79 Khomeini revolution wasn’t simply a populist, right-wing and fundamentalist uprising, but that for the first year or two there was something genuine happening. This is what Mousavi is after, whereas it is the strategy of Ahmadinejad to transform Iran into a new generation of Ayatollah-like wealth. Recent events demonstrate that the mapping of Tehran as the poor, fundamentalist, Islamic farmers in the south vs. the educated, secular Western north is proven wrong. Here we have a genuine third way in which Islam is practiced. Something has happened, a great rebellion against the regime, no doubt, but on behalf of the emancipatory dimension of the Islamic self, and one way western liberals deal with this is to dismiss it as a mosque full of Western clerics exploiting the popularity of Islam; which coincidentally is what Ahmadinejad is claiming. I feel this proves that Islam can exist politically, not only as a Turkish, pro-market Islam or a fundamentalist Islam, but also an emancipatory Islam. When Western liberals praise Islam, it is always the Islam of the 10th or 11th Century, but we needn’t look back this time, we can look at the present! People who are around it have a very ambiguous attitude towards it, which means that something new is happening here. This is not the guild that spoiled the middle class youth and the poor workers; it is a genuine emancipatory event, which blurs the line between liberals and fundamentalists.

Populismo

Me gustaría comenzar con un punto teórico y, sin embargo, obsceno. Considero que la siguiente anécdota es maravillosa porque da cuenta de cómo funciona la democracia: durante una batalla crucial entre los ejércitos de Prusia y Austria en el siglo XIX, el rey prusiano observaba la batalla con preocupación porque no sabía quién estaba ganando. A su lado estaba el genio detrás de la batalla, el general Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, un gran estratega. Sin dejar de mirar lo que parecía ser una confusión total en el campo de batalla le dijo al rey: “Permítame ser el primero en felicitar a Su Majestad por tan brillante victoria”. Esta es la distancia que hay entre los maestros solemnes y el conocimiento. El rey era el señor y el comandante formal, pero no había entendido lo que pasaba en el campo de batalla. La victoria era para el general von Moltke, el estratega, quien ayudó y felicitó al rey en nombre de lo que él mismo representaba. Esta idea de no saber lo “brillante” que uno puede ser hasta que alguien más te informe de tu genialidad sería la misma metáfora si reemplazáramos al rey con el pueblo. Así es exactamente como funciona la democracia. A nosotros, el pueblo, nos informan en las elecciones que obtuvimos una brillante victoria.

Con este ejemplo no pretendo denigrar al pueblo, al contrario. No me interesa jugar el típico papel de crítico liberal. Mi problema es que creo que la verdad no está en los extremos. Para ser auténtico no necesito irme a los extremos. Cuando era joven, el irse a los extremos traía consigo la idea de que eso era algo auténtico. Yo no estoy de acuerdo. Casi podría decir que me encuentro del lado de la gente común.

Ahora bien, se puede decir que el problema del pueblo es el populismo y sí, estoy de acuerdo, aunque no voy a hablar de ello en este momento. Sigo en desacuerdo con Ernesto Laclau; estoy convencido de que el populismo es algo sobre lo que se requiere reflexionar cuidadosamente. Intento demostrar que de la democracia al populismo se necesita algo más, y es ahí donde reside el problema en la maravillosa serie de ideas del razonamiento de Laclau.

¿Estamos de acuerdo en que Laclau, en su libro, considera a Tito y a Mao Tze Tung como populistas? Bueno, yo simplemente confío en mi intuición espontánea para decir que si ellos son populistas, entonces el concepto está utilizado de manera incorrecta. Yo coincido, para manejar los propios términos de Laclau, en que una parte crucial del populismo consiste en confundir y poner los antagonismos fuera de lugar. Su reacción sería decir que los antagonismos son exhibidos y que no hay antagonismos auténticos. Yo creo que todavía se puede mostrar que hay antagonismos, pero no en el sentido de la lucha de clases.

Tanto el antagonismo como el populismo, según intento argumentar en defensa de Laclau, son confundidos de una manera formal y para ser populista (usando los términos del propio Laclau) uno debe reconocer que la gente existe y que son una amenaza exterior. Ése es el nivel cero del populismo. Para ponerlo en términos marxistas tradicionales, existen antagonismos radicales que son constitutivos de las comunidades. Un principio elemental del populismo dice que debe haber un mínimo de orden y algún intruso externo (el imperialismo, el comunismo, etcétera). La causa viene del exterior destruyendo el orden natural. En otras palabras, afi rmo que el populismo siempre está sostenido por un tipo de desesperación frustrada: “No sé qué está pasando pero debe terminar”. El populismo tiene la fi rme creencia de que debe haber alguien responsable por todo el desastre, y por ello necesita un agente tras bambalinas. En este negarse a saber reside el verdadero fetichismo que el populismo no nombra. Aunque a nivel puramente formal el fetichismo involucra un gesto de transferencia sobre el sujeto del fetiche, funciona como una inversión exacta de la fórmula estándar de transferencia con el sujeto que supuestamente conoce. A lo que el fetiche da cuerpo es precisamente a mi rechazo por asumir subjetivamente lo que sé. ¿Queda claro cuál es mi punto? No creo que la gente sea estúpida, ni que tenga una mínima voluntad, pero escoge la estupidez voluntariamente. Detrás del populismo siempre hay algo de No quiero saber. Aun si no es algo reconocido, está implícito. En términos nietzscheanos, el populismo es una estrategia reactiva.

Libertad

El rechazo a saber nos confronta con el estancamiento, como solemos llamarlo, de nuestra sociedad de elección. Existen múltiples inversiones ideológicas en el tema de la elección. Como probablemente el lector sabe, los científi cos especializados en estudios del cerebro señalan que la libertad de elegir es una ilusión. Experimentamos que somos libres cuando somos capaces de actuar de la manera en que nuestro organismo nos determina a actuar. Esta es la suave cognición de la redefi nición de libertad. No niega la libertad, sólo nos dice que la libertad no es lo que uno cree. Libertad signifi ca que aun cuando no haya obstáculos que te impidan darte cuenta de lo que quieres de pronto, aún estás determinado por tu propia naturaleza inmanente. Sin embargo, Benjamin Libet defi ende la libertad humana. El nivel cero de la libertad no se utiliza para elegir sino para bloquear o para decir no a nuestra decisión.

Los economistas liberales enfatizan la libertad de elección como el ingrediente clave de la economía de mercado. Al comprar cosas, de alguna manera estamos votando continuamente. A los pensadores existencialistas más profundos les gusta realizar variaciones sobre el tema de la auténtica elección existencial, donde el verdadero corazón de nuestro ser está en riesgo; se trata de una elección que involucra un compromiso existencial absoluto, en contraposición con las decisiones superfi – ciales de elegir estos o aquellos productos.

En la versión marxista de este tema, la multiplicidad de opciones a elegir con las que el mercado nos bombardea obnubila la ausencia de verdaderas elecciones radicales que conciernen a la estructura fundamental de nuestra sociedad. Tal es la crítica marxista común: puedes elegir entre Coca-Cola o Pepsi y cosas parecidas, pero no puedes hacer una elección más radical. Sin embargo hay un rasgo que, a mi parecer, se pierde de vista con frecuencia: el que haya un requerimiento a escoger cuando dejamos ecuánimes las coordinaciones cognitivas básicas para tomar una decisión. Leonardo Padura (el escritor cubano autor de la tetralogía Habana) escribió en una de sus novelas: “Es terrible no conocer el pasado y aún así ser capaces de impactar el futuro”. Así que nuestra condición básica es estar obligados a tomar decisiones en una situación que permanece opaca. En la elección estándar de la primera situación, lo único que nos queda es hacer el gesto vacuo de pretender que conseguimos libremente el conocimiento que el experto impone. Pero, ¿qué sucede si la elección es realmente libre y es por esta razón que la experiencia es más frustrante? Entonces nos encontramos en la posición de tener que decidir constantemente sobre asuntos que afectarán nuestras vidas de manera fundamental, pero que carecen de una base fundamentada en el conocimiento. Cito a John Gray: “Hemos sido lanzados en una época en la que todo es provisional. Nuevas tecnologías alteran nuestra vida diariamente. Las tradiciones del pasado no pueden recuperarse. Al mismo tiempo, no tenemos ni idea de lo que traerá el futuro. Estamos obligados a vivir como si fuéramos libres”.

Esta presión por elegir no solamente involucra la ignorancia sobre el objeto de nuestra elección. Somos bombardeados por anuncios que nos piden que hagamos una elección sin estar realmente califi cados para hacer la elección adecuada. Peor aún, estamos invadidos por la imposibilidad de responder a la pregunta del deseo. Cuando Lacan defi ne el objeto del deseo como algo perdido, no se refi ere simplemente a que nunca sabemos lo que deseamos y estamos condenados a buscar por siempre el verdadero objeto. Lo que Lacan quiere decir es algo más radical: el objeto perdido es, en última instancia, el sujeto mismo. El sujeto como objeto implica que la pregunta del deseo, su enigma original, no es básicamente “¿qué quiero?”, sino “¿qué quieren los otros de mí?”, “¿qué objeto ven en mí?” Por lo cual, a propósito de la pregunta histórica de “¿por qué soy ese nombre?”, “¿por qué soy lo que dices que soy?” Lacan afi rma que el sujeto como tal es histérico. Él defi ne al sujeto como aquello que no es un objeto. El punto aquí es que la imposibilidad de identifi carse a sí mismo como un objeto, el no saber lo que uno es para los demás, es constitutivo del sujeto. De esta manera, Lacan genera la total diversidad de posturas subjetivas patológicas, leyendo esta diversidad como la diversidad de las respuestas que hay a la pregunta histérica. El psicótico se sabe el objeto de placer de los otros, mientras que el pervertido se deposita como el instrumento del placer de los otros y así sucesivamente. Es por esto que sostengo que hay una dimensión terrorista en la presión por elegir. Este terror resuena, al menos para mí, incluso en la pregunta más inocente; por ejemplo, cuando uno reserva una habitación en un hotel. ¿Almohadas suaves o duras?, ¿cama matrimonial o camas separadas?, etcétera. Debajo de este simple cuestionario hay un sondeo mucho más radical: “Dime quién eres, ¿qué tipo de objeto quieres ser?, ¿qué llenaría la profundidad de tu deseo?”. Es por esto que creo que la aprehensión anti-esencialista sobre las identidades fi jas que planteaba Michel Foucault, esa urgencia incesante por ejercitar el cuidado del ser, por reinventarse continuamente, por recrearse uno mismo, encuentra un extraño eco en las dinámicas del capitalismo posmoderno. Ya estaba, desde luego, el viejo existencialismo que afi rmaba que un hombre es lo que él hace de sí mismo, y el existencialismo unió esta libertad radical con una ansiedad existencial. Pero para el existencialismo, la ansiedad de experimentar la propia libertad, la falta de una determinación sustancial propia, era el momento auténtico cuando el sujeto veía su integración en la fi jeza del universo ideológico dado. Lo que el existencialismo no era capaz de prever fue lo que Adorno intentó condensar en el título de su ataque en contra de la palabrería de Heidegger sobre la autenticidad; cómo la ideología hegemónica moviliza directamente la falta de una identidad fi ja para sostener el proceso interminable de la auto-recreación consumista, ya sin reprimirla. Así que para volver una vez más a este eterno y ya aburrido debate con Judy Butler, la cuestión no es que yo no esté de acuerdo con el mismo, pero creo que precisamente este eterno auto-cuestionamiento dinámico y nómada que siempre sostiene esta ansiedad ambigua: “¿Estás listo para admitir quién eres?”, es el nivel en el cual el consumismo te hace culpable. No en el sentido simple de: “Nunca obtienes el gozo total que quieres del producto adquirido”. Sin embargo, se supone que siempre escoges libremente lo que quieres de verdad; aunque, desde luego, nunca puedes.

Democracia

De alguna manera el consumismo siempre te hace ver como no-auténtico. Con la difi cultad para elegir, el populismo y demás como tela de fondo, me gustaría abordar el tema de la democracia. Hay una distinción entre dos tipos o, mejor dicho, niveles de corrupción en la democracia. La corrupción empírica de facto y la corrupción que está ligada a la forma misma de la democracia, que es la reducción de la política a la negociación de intereses privados. Esta brecha se vuelve visible en los casos auténticos (y extraordinarios) en los que un político democrático y honesto, mientras lucha en contra de la corrupción empírica, sostiene, sin embargo, el estado formal de la corrupción.

Utilizando los mismos términos de Walter Bejamin acerca de la distinción entre la violencia constituida y la violencia constitutiva, uno podría decir que aquí estamos tratando con la distinción entre la corrupción constituida (romper las leyes, etcétera) o más bien, la corrupción constitutiva de la forma democrática de gobierno misma. La democracia electoral sólo es representativa en tanto que primero es la representación consensuada del capitalismo, que es hoy la economía de mercado. Creo que uno debe seguir esta línea en el sentido estricto trascendental. El nivel empírico, desde luego, es cómo la democracia liberal multipartidista representa y refleja las opiniones cuantitativas y dispersas de las personas, lo que piensan sobre los candidatos y demás. Sin embargo, antes de este nivel empírico, en un sentido mucho más radical, la democracia multipartidista representa una cierta visión de la sociedad, la política y el papel que juega el individuo en ella. La democracia multipartidista representa una visión precisa de la vida social en que la política está organizada en partidos que compiten a través de las elecciones para ejercer un control sobre los aparatos legislativo y ejecutivo del estado. Uno debe estar consciente de que este marco trascendental de la democracia nunca es neutral; privilegia ciertos valores y prácticas. Esta no-neutralidad se vuelve palpable en el momento de crisis cuando experimentamos la incapacidad del sistema democrático de registrar lo que la gente quiere o piensa verdaderamente. Recuerdo las elecciones del 2005 en el Reino Unido. A pesar de la creciente antipatía hacia Tony Blair —la gente en su momento votó por él como la persona menos popular del Reino Unido—, ganó las elecciones. Algo estaba muy mal. No era que la gente no supiera lo que quería, más bien era su cínica resignación lo que les impidió actuar en consecuencia. Por lo tanto el resultado guardaba una extraña distancia entre lo que pensaba la gente y cómo votaba. En esta crítica el privilegio jacobino de la virtud es discernible. En la democracia no hay lugar para la virtud. Mi conclusión es que podría tratarse de una animosidad hacia el acto de votar, sugiriendo que no hay autenticidad en ello.

No hay razón para despreciar las elecciones democráticas, el punto es sólo insistir en que no son capaces de expresar la verdad por sí mismas a priori. Por regla general suelen reflejar una doxa predominante, determinada por la ideología hegemónica.

Irán

Mi idea es que esto es exactamente lo que está pasando en Irán. ¿Por qué? Primero echemos un vistazo a este tipo de evento. Aún cuando una fuerza opresiva no pierde el poder, en algún punto hay un tipo de descanso psicológico cuando todos saben que algo ha terminado. El libro de Richard Kapuchinski trata de aislar este momento y asegura haberlo encontrado. Tres o cuatro meses antes de que el Shah abandonara el país hubo manifestaciones en algunos suburbios de Teherán. Las personas se juntaron en un cruce cuando la policía se les acercó y les gritó. Un hombre miró a un oficial y no hizo nada. El policía volvió a gritarle, pero el tipo se quedó mirándolo. Entonces el oficial de policía, avergonzado, dio media vuelta y se fue. El misterio es cómo, en un par de horas, todo Teherán se había enterado. Fue un tipo de subversión mística. La gente seguía muriendo, pero a partir de ese instante todos, incluso los que estaban en el poder, sabían que el juego había terminado.

Para mí, este momento de la transición es el más interesante. Yo describiría la historia de la descomposición del socialismo en estos términos. ¿Cuándo supo con exactitud la gente que el comunismo había terminado de verdad? Algo similar ocurrió después de la segunda noche después de las elecciones iraníes. Es como enamorarse: uno no decide enamorarse, uno sólo sabe que está enamorado. La gente descubrió que no tenía miedo. La policía podía golpearlos hasta matarlos, pero las personas seguían saliendo por cientos y miles. El modo en que esto sucede es aterrador en un buen sentido; el poder sublime de la gente. Mucho más amenazador que los gritos es el silencio: literalmente había cientos y miles de personas caminando en silencio por las calles. Después se subieron a los techos, casi como un ritual, y gritaron ¡Alla wa akbar!, ¡Dios es grande! Y éste es un dogma crucial, ¿por qué? Porque combinado con el color verde, el color del Islam, esto comprueba que la gente ya no tiene miedo. Es algo que los comentadores occidentales olvidan sistemáticamente y si lo reconocen, le asignan un papel secundario.

Aquí viene mi primer punto importante: este Mousavi no es el candidato liberal pro-occidental que los medios de comunicación dicen que es. Según los medios hay dos grupos básicos en Irán: la pobre y primitiva mayoría islámica, integrada por agricultores que son manipulados por los clérigos, y la educada y secular clase media pro-occidental, que sólo quiere vivir la democracia después del Shah. El otro candidato, Mehdi Karroubi, es el candidato occidental que quería probar algunas políticas de identidad diciendo: “Tenemos mujeres, kurdos, homosexuales, etcétera, apóyenme y su identidad será reconocida”. Lo que Mousavi está haciendo es completamente distinto. Su misión es volver a los orígenes, repetir la revolución de 1979. Me gusta la idea de que tenga la autoridad de Khomeini detrás, y que Mousavi no sea un estúpido arquitecto incompetente, porque es arquitecto de profesión. Durante toda la guerra Irán-Irak, él era el primer ministro y en ese entonces había organizado una economía de trabajo. Su idea actual es volver a las raíces del 79. Su eslogan dice que él no es nadie y que la gente se organizará sola. Dejando toda la crítica irónica de lado reconozco que la revolución de Khomeini del 79 no fue un simple levantamiento fundamentalista y populista de derecha; durante los primeros uno o dos años estaba sucediendo algo genuino. Esto es lo que Mousavi busca, mientras que la estrategia de Ahmadinejad es transformar Irán en una nueva generación de riqueza al estilo Ayatollah. Los hechos recientes demuestran que el trazar un mapa de Teherán con agricultores islámicos, fundamentalistas y pobres en el sur contra los occidentales, educados y seculares del norte es incorrecto. Aquí tenemos una auténtica tercera vía en la que se practica el Islam. Algo ha sucedido; una gran rebelión en contra del régimen, sin duda, pero en nombre de la dimensión emancipadora del ser islámico, y una manera en que los liberales occidentales lidian con esto es descalificando dicha rebelión como si fuera una mezquita llena de clérigos occidentales que explotan la popularidad del Islam, que casualmente es lo que Ahmadinejad está reclamando. Creo que esto comprueba que el Islam puede existir políticamente, no sólo como un Islam turco y a favor del mercado, o bien fundamentalista, sino como un Islam emancipador. Cuando los liberales occidentales elogian el Islam siempre es el Islam de los siglos X u XI, pero no necesitamos mirar hacia atrás esta vez, ¡podemos ver el presente! La gente que está alrededor tiene una actitud ambigua hacia él, lo que significa que algo nuevo está sucediendo. Este no es el gremio que echó a perder a la juventud de clase media y a los pobres trabajadores; es un evento genuino y liberador, que desdibujará la línea entre liberales y fundamentalistas.

We need more articles like this one