Three Travellers in Mexico

Tres destinos en México

Rosemary Sullivan

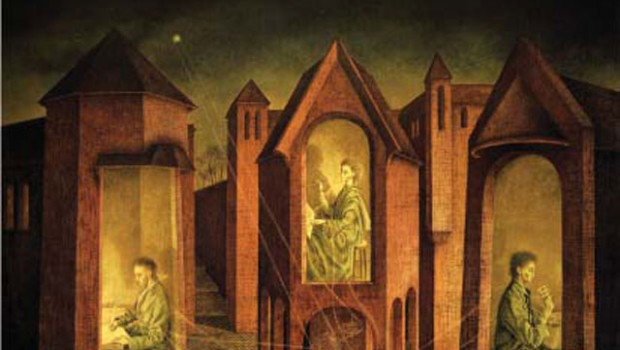

Three monk-like, sexually ambiguous figures sit in castellated towers. A soft light shines in each room, focused from a different interior source. One figure is a painter, one a writer, and one sits drinking from a cup of wine. Each is independent, each unaware of the other. Yet, hovering in the air, a barely visible spindle connects the three figures to a distant star. The artist described this as “a complicated machine from which come pulleys that wind around them and make them move (they think they move freely) … [but] the destiny of these people…unbeknownst to them, is intertwined and one day their lives will cross.”

The artist is the great Spanish-Mexican painter Remedios Varo, and three lives did eventually cross, pulled as if by synchronicity to act out the narrative of her painting, three women who, independently, had carved the same artistic vision. It was a magic meeting, the meeting of P.K. Page, Remedios Varo, and Leonora Carrington in Mexico in 1960. They were antic, hilarious, and deeply committed to their art.

What was that friendship like? We are so used to the traditional scenario of the young woman artist taken under the mentorship of the older male artist. Each of these women had had that kind of experience in their youth, when they played the muse at the centre of an artistic circle–Carrington and Varo for the surrealist circles in France; Page for the Preview poets in Montreal. What would it be like to glimpse inside the process of imaginative cross-fertilization when it is taking place entirely in the context of female friendship?

Page is among Canada’s foremost writers: author of over a dozen books of poetry; a novel The Sun and The Moon; short stories, one of which, “Unless the Eye Catch Fire,” has been made into a play and a film; a travelogue, Brazilian Journal; and half a dozen books for children. But under the name of P.K. Irwin, she is also a painter. A number of her works can be seen in the National Gallery of Canada.

I first met P.K. in 1974. She had just published an article called “Traveler, Conjuror, Journeyman,” in which she described art as magicianship; the point of art is to alter our way of seeing. I liked this, but it was her voice, so candid and playful, that made me want to seek her out. I still remember that first visit. Her suburban home in Victoria, British Columbia, looked ordinary on the outside, but entering it was like walking into an exotic mind: on the shelves of her living room there were Mexican candied skulls and gaudily painted trees of life, Mexican paper flowers and Australian bull roarers, and her walls were filled with her own paintings–one was of strange strings of dancing vegetation reaching towards the sun through scarlet air; another of stippled silver moons. We became friends after that visit. We used to trade our dreams. I recall her telling me of her dream about two dogs–they were Irish setters, but golden in colour. Above their eyes as they stared up at her was a third blue eye which was human. The thought of the dream was: if their third eye is human, what is our third eye? She could play wonderful linguistic games: “There is no difference between there and here except for an irrelevant, inconsequential ‘t.’” Once she said to me: “If the world is a plant, perhaps you are a nodule of growth.” For me P.K. is one of the searchers, ahead of the rest of us, throwing back clues. She encouraged me to believe I might one day become a writer.

She also introduced me to the paintings of Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo and spoke of their time together in Mexico. Intrigued by that friendship, I decided to go to Mexico in search of them.

Buzzed through by an attendant guard, I walked into the Galería Arvil in the Zona Rosa in Mexico City. For its twenty-fifth anniversary exhibition, Arvil was featuring works by Carrington and Varo. I knew these paintings from books but this was the first time I had seen them in the flesh as it were. How to describe their impact on me?

Leonora Carrington’s paintings had titles like “Monopoteosis,” “Hierophant,” “Reflections on the Oracle,” “Penelope,” and “Took My Way Down, Like a Messenger to the Deep.” They seemed to move in a vortex of light that pulled the viewer in and I had a sensation of bouleversement, being turned on my head–I was travelling into the paintings drawn by a will stronger than my own. What was she telling me about light, space, time? And beside her was this other strange myth-maker. Varo canvases were filled with complicated alchemical mechanisms, creatures of inverted heads and alembic bodies, heads emerging from walls. One painting was called “The Lovers.” A couple, holding hands, had faces of mirrors and they were lost in each other’s eyes. Their magnetic attraction was so great that it rose as a whirl of steam from their blue matching clothes, then condensed as water drowning their feet, and the space around them was mysterious, black and stippled with falling light. Another was called “Farewell.” The lovers had separated and were just visible disappearing down adjacent corridors, but their shadows, still tied to their feet, stretched back to take a last kiss. This woman was telling stories and she had lived deeply.

Varo had died in 1963 at the age of fifty-five, but I was able to meet Leonora Carrington. Her New York and Mexican galleries had tried hard to discourage me, insisting that she now refused all interviews, but the fact that I was carrying greetings from Pat (as Leonora called P.K.) meant that she kindly invited me without hesitation to visit her. The po“Traveler, Conjuror, Journeyman,” in which she described art as magicianship; the point of art is to alter our way of seeing.rtrait of their friendship was as delightful as I had expected. This is the story.

When P.K. Page arrived in Mexico City in 1960 as the wife of the Canadian Ambassador, it is not likely that the Canadian embassy had seen her kind of woman before. She was forty-four, and already a successful writer, with a novel, several books of poetry and a Governor General’s Award behind her. They had just completed a four-year posting in Brazil before they arrived in Mexico. For P. K., Brazil had been a dazzling experience, a flamboyant world of Doric palms and flowering jungles, and she had turned for the first time to painting to fix the whirl of images. In Mexico, because of her, the ambassadorial residence on Montes Carpatos was suddenly filled with artists.

One evening after a dinner party, P.K. found herself recounting a strange experience from her childhood. She and her mother were standing looking from the living room window of their home and suddenly found themselves staring into the eyes of a completely terrifying creature who was watching them. “It looked,” she says now, “like current descriptions of aliens: round dark eyes like disks, pointed chin, narrow with languorous hair, soft like a baby’s, as if it were under water almost.” The creature was not threatening, but it frightened her. She turned to her mother, who had also seen it, and her mother quietly closed the blind. Little did she know who was in her audience as she recounted her story that night. Leonora Carrington approached and said: “It sounds totally true.” Others would have dismissed the story as fantasy or eccentricity. For Leonora this was elementary stuff, but it had verisimilitude. They became immediate friends.

Carrington was by then already famous in Mexico. She had just had a one-woman show that had filled the Belles Artes national gallery and was revered as the country’s leading surrealist. P.K. remembers her as tall and narrow, with exquisite eyes. “I always used to say she could slip through a crack in the door, as if she had one finger and one toe less than the rest of us, her physical self was so narrow.” One detail of her past life that everyone knew was that she had been the lover of Max Ernst, the don of European Surrealism, but this is the least remarkable thing about her.

Carrington was born in Lancashire in 1917, the child of a wealthy industrialist. A fleet of servants ran the family residence, Crookhey Hall, and a Jesuit came Sundays to give mass in the family chapel. Her Celtic mother was a remarkable beauty; when she took Leonora to make her debut at the court of King George V in 1934, she advised her rebellious young daughter to look decorative and added, “You’d better be careful or you’ll be an old witch before you’re twenty-five.” Leonora decided she’d rather be the witch. After being sent to finishing school in Florence, followed by school in Paris where she spent her time drawing and climbing out of windows to escape, she convinced her parents to allow her to study art and enrolled at the Amédée Ozenfant Academy in London in 1936. A friend invited her to dinner with Max Ernst, a married man of forty-six. The encounter was electric. They fled to Paris.

They had three years together, but it was a terrible time to be romantic lovers. Ernst was arrested twice–by the French in 1939 as an enemy alien and then again by the Vichy regime in 1940. Leonora fled across the Pyrenees to Spain but the psychic pressure of Ernst’s double internment was leading to disaster. In Spain she began to spiral out of control, under the pressure of fear. She was institutionalized in Santander and her experiences of shock and drug therapy were so horrendous she came to call them “death practice.” Her parents sent her nanny from England to fetch her. Convinced their intention was to ship her to hospital in South Africa she persuaded her keeper to take her shopping in Lisbon. A lady, she explained, could not travel without gloves and hat. Demanding to stop at a café to go to the bathroom, she slipped out the back door and fled to the Mexican Embassy where an acquaintance, the poet-diplomat, Renato Leduc, agreed to marry her so that she could get out of Spain. In New York, she found that Ernst had become involved with Peggy Guggenheim. In 1942, she set out with Leduc for Mexico City where many refugee artists were settling. Established in the abandoned Russian Embassy, she wrote the whole experience in a story called “Down Below,” possibly one of the most lucidly hallucinatory accounts of madness that has been written. “At least when you go mad you find out what you are made of,” she said to me laconically.

In Mexico, which offered citizenship and help to refugees the rest of the world wouldn’t take, she met the painter Remedios Varo. Varo’s escape had also been spectacular.

Born in Catalonia in 1908, Varo had joined the surrealists in Paris where she had become the lover of the noted surrealist poet Benjamin Péret. When the Nazis invaded in June 1940 and hoisted the swastika atop the Eiffel Tower, Varo fled with eight million other refugees in cars, on bicycles or pushing wheelbarrows, towards the unoccupied zone in the south. She eventually joined Péret in Marseille. A New York group called the Emergency Rescue Committee had set itself up three days after the Nazi occupation of Paris with the express purpose of saving as many of Europe’s leading intellectuals and artists as possible. A thirty-two-year-old Harvard-trained classicist, Varian Fry, was sent to Marseille in August 1940 with $3000 strapped to his leg and a list of names which had been composed in New York. He established a safe house called the Villa Air-Bel to begin the rescue mission. Péret was famous enough to earn a spot there, which required establishing one’s credentials as an intellectual worthy of attention.

The committee wrote frantically to the U.S. to raise the fare for Péret and Varo–the price of saving the life of one escapee was $350. The process moved at a snail’s pace and, while food became more and more scarce, the secret police searched the premises for signs of subversion. It took well over a year to find safe exit, but passage was finally secured for Varo and Péret from Casablanca in November 1941. Still they had to get to North Africa. Péret negotiated with a black-market operator to take them across. Luckily for them their money was stolen on the docks before they found the fishing boat, since it was discovered that the black-marketeer they had hired was a psychopathic killer who had murdered the previous refugees he was meant to save; twelve bodies were found buried in his backyard. Varo and Péret did finally reach Mexico at the end of 1941. They had thought of the U.S., but the Americans refused Péret refuge because of his political record. Mexico offered automatic citizenship to all Spanish refugees and protection to any members of the International Brigade.

From the moment of Remedios’s arrival she and Leonora became intimate friends, seeing each other nearly every day, studying alchemy together and exchanging dreams.

By 1960, Remedios too was famous. She had been commissioned to do a mural for the new Cancer Pavilion of the Medical Centre and her paintings were selling well. She still kept her surrealist roots, writing an essay in 1959 called De Homo Rodans, a pseudo-scholarly treatise on the origins of man and of the first umbrella. She and Leonora were treated with awe as two eccentric geniuses. Their antics owed something to the old surrealist sense of play. When she had a party, Remedios would search the telephone directory under psychiatrists and, finding a likely name, call doctor so-and-so, daring him to come. The meals she and Leonora put together were famous: for example, serving rice coloured with squid’s ink as caviar. Remedios’s sense of humour surfaces in paintings like “Vegetarian Vampires who keep Animals as Pets.”

To me these two women offer a model of women’s friendship, rebelling against all constraining conventions and using humour as their weapon of choice. One of Varo’s most amusing paintings is called “Woman Leaving the Psychoanalyst.” A robed female, her mask sliding from her face, is shown departing from a stone building; in her hand she dangles a shrunken head. Varo explained: “The patient drops her father’s disembodied head into a small circular well … [which is the] correct thing to do when leaving the psychoanalyst … the basket she carries holds yet more psychological waste.” The psychoanalyst’s name is Dr. FJA, a reference to Freud, Jung, and Adler. They were even able to make the erotic funny. Perhaps rebounding from her Ernst encounter, Leonora could say: “If you have to, get on with your genital responsibilities, but I won’t be the Lady of Shallot.” When André Breton asked her to participate in an exhibition of eroticism in 1959, she described her intended contribution: “A Holy Ghost (albino pigeon) three meters high, real feathers (white chickens’, for example), with: nine penises erect (luminous), thirty-nine testicles to the sound of little Christmas bells, pink paws … Let me know, Dear André, and I will send you an exact drawing …” She came to dislike the heroic myth of artistic genius, the grandiose gesture: “Painting is like making strawberry jam–really carefully and well.”

When Leonora discovered that P.K. could speak her language, she immediately invited her to her studio. At that time P.K. had progressed in her painting from gouache to oil, but was finding the process unsatisfactory. Leonora insisted she try egg tempera, giving her her own private recipe. When P.K. responded that she didn’t know how to use it, Leonora replied: “Find out.” P.K. developed her own technique, putting on expansive swaths and then scraping and cutting through, loving it immediately because it dried so quickly she could touch it. “It was my idea of bliss.” They would race around Mexico in P.K.’s car, negotiating the gloriettas where the traffic merged from eight different directions, hunting gold leaf and pigment. P.K. also helped Leonora with the production of her surrealistic play Penelope, assisting in the labour of making papier-mâché sets, costumes, and masks for the characters that included a fabulous and omniscient rocking horse and an oracular nurse dressed in her true character as a cow goddess.

In her own version of surrealism, Leonora used everything to advantage for humorous or provocative purposes. When P.K. walked into her studio one day, she discovered her working on a “thing.” She had found some boards lying around and knocked them together, painting them black and boring holes in them. Over the holes were absurd little titles. She said: “You put your fingers through the holes. In one hole there was the sharp end of a thumb tack, in another face cream, in another soot,” P.K. explains. “It took courage to put your finger through those holes. You realize how vulnerable the blind finger is. Grown men refused Leonora’s experiment.”

P.K. remembers their times together as often hilarious, especially a dinner party at Leonora’s house. Leonora had phoned that morning to complain that the other couple who had been invited were insisting on bringing a Dr. Stern with them. Leonora was always uneasy with people whose imagination stopped at “too low an octave,” and a stranger at her table was disconcerting. The only Stern she knew was a Mexican urologist. The dinner was quite respectable by Leonora’s standards: the toilet paper and ketchup bottle that usually graced the table had been removed. Wringing her hands anxiously Leonora launched into a string of questions about urology over dinner, until her guest interrupted indignantly: “Leonora, do you know who you have at your table? Only the greatest violinist in the world, Isaac Stern.” The conversation then turned somewhat awkwardly to art and someone asked if Stern liked to play for himself. He responded that he could only play for an audience. Asked if he could not go into a room by himself and play for the sheer joy of it, he replied that he could not. Both P.K. and Leonora were horrified. Why do you paint, he asked, if not for an audience? P.K. remembers one of them saying: “For God, which was a fairly pompous reply but we meant for ourselves or perhaps a higher being.” Isaac Stern replied that anyone who could say that was a “liar.” “By this time,” P.K. explains, “I was filled up to my gullet with red wine and, outraged at his comment, I picked up my glass and threw it over my shoulder. It went through a window behind me and crashed on the cement entrance way downstairs.” As a rhetorical response to the maestro’s condescension, Leonora thought this a brilliant gesture. The next day Leonora sent Stern a bouquet of flowers, telling P.K. that, though Stern would miss it, there was a message in the flowers. Each flower had a meaning. She had looked it all up.

There were many other antic parties. P.K. recalled the embassy reception held in honour of the dazzlingly beautiful Maria Felix, considered the Sophia Loren of Mexico. When she warned the house staff of the actress’s imminent arrival, the news spread like a brush fire and suddenly brothers, sisters, cousins, nieces, all the staffs’ extended family, arrived at the doorstep to see the star. The head butler had a nose bleed at the shock and bled all over his white gloves so that he had to borrow his subordinate’s which were three sizes too big, making him look like a good stand-in for Mickey Mouse. At another party given for Kathleen Fenwick, Curator of Prints and Drawings at the National Gallery of Canada, P.K. remembered that one of the invited artists was Remedios Varo. The Canadian society columnist, Zena Cherry, had just arrived from Italy sporting the latest fashion in shoes. Instead of heels, the shoes had fixed wheels. Remedios was beside herself. For years she had been painting wheeled shoes on her figures, and she was desperate to have the shoes. The more cocktails she drank the more importunate she became until finally P.K. turned to Cherry and said: “Oh, give her the damn shoes. Can’t you see she needs them?” Cherry remained poker-faced and left the party.

P.K. was deeply fond of Remedios, but they could not communicate verbally, Remedios’s flights of poetic Spanish being too hard for her to follow, but according to Remedios’s husband, Walter Gruen, Remedios came to depend on P.K. and her husband Arthur Irwin. The legacy of her wartime experience had left her terrified of governments and deportations, and she always believed that Irwin would save her when the worst inevitably came to the worst.

One thing the three women had in common was their interest in space, time, and other dimensions, and in the spiritual. They were questers. They talked of Jung, whose work they were reading together; about levels of awareness; about things that seemed vital and absolutely essential. One of the paintings Remedios did at the time, called “The Phenomenon of Weightlessness,” would later be used by the physicist Peter Bergman for the cover of his book The Riddle of Gravitation. Working intuitively, she had got the phenomenon exactly right. They also conducted their own experiments. P.K. remembers the three of them lying naked on a bed, laying their hands over each other’s backs to determine at what distance from the body they could feel the pull of the magnetic field.

Each was different: Remedios more allegorical, perhaps intellectual, and fascinated by mystic disciplines: one painting called “Spiral Transit” evokes the medieval notion of an initiatory rite or The Call. Leonora would explain that her paintings were based on hypnagogic visions, not on dreams. To a Freudian who once claimed she was not adjusted, she replied: “To what.” She was also the most feminist. In the foreword to the catalogue of one of her exhibitions she wrote that there are gaps in our understanding, wisdom covered up, and “the Furies, who have a sanctuary buried many fathoms under education and brain washing, have told Females they will return, return from under the fear, shame, and finally through the crack in the prison door … [give us back] the Mysteries which were ours and which were violated, stolen or destroyed, leaving us with the thankless hope of pleasing a male animal, probably of one’s own species.” P.K. was the most verbal, interested in the pressure of interiority and the idea of symbolic patterns. In retrospect she would describe her time in Latin America. “If Brazil was day, then Mexico was night. All the images of darkness hovered for me in the Mexican sunlight. If Brazil was a change of place, then Mexico was a change of time. One was very close to the old gods here … [where] objects dissolved into their symbols … Coming as I do from a random or whim-oriented culture, this recurrence and interrelating of symbols into an ordered and significant pattern … was curiously illuminating … The dark Mexican night had led me back into myself and I was startlingly aware of the six dimensions of space.’

But none of them easily ascribed to systems. P.K. remembers that Leonora introduced her to the writings of Gurdjieff, but she also told her that when she was asked to a Gurdjieff group in Mexico, she found she couldn’t stand it, all the people sitting around looking so poker faced. She had finally got up and stamped–just one leg–and recited: “You can tell by moulds that their flesh hangs in folds / You can tell by their smell that there’s blood in the well.” She told P.K. this with laughter in her eyes. They had asked her to leave. P.K. believed that Leonora would have been unable to follow anybody else’s lead. “She’s such an original. She’d probably have to go her own way.”

But she felt Leonora did lead her, “into places that nudged you into remembering that you knew those places almost, couldn’t quite get your hands on them, but they weren’t totally foreign. She activated some part of my imagination and mind that normally wasn’t activated in me. She knew that we are not whole and we want very much to be whole. She’s not like the rest of us. She would say ‘Despise nothing, ignore nothing; create interior space for digestive purposes.’”

They had often talked about transmutation, how to change the core of your being. “Once she asked me: ‘What does it mean to you if I say: Going backwards very, very fast, counter-clockwise, into a small black hole.’ It didn’t mean anything to me at all. She said: ‘That’s the way you get back into your body when you’ve been out.’ I believed her of course, that she could get out of her body. I think we’re very gross matter. The finer matter is there, but only a few people can get at it, and a few of us have glimpses sometimes. Life demands that we stay with the gross matter. But Leonora was very strong. You know the finer matter is as strong as adamant. It is the gross matter that bleeds.”

In 1962, Remedios Varo died suddenly and unexpectedly of a heart attack. “Everything came to a blinding halt when she died,” P.K. said. “I remember we called on her husband Walter [Gruen] and there was a circle of chairs in the room. Walter wasn’t there. Nobody knew anybody else and nobody knew how to get out of that room. So there we sat. It was as if Remedios had done that to us. Frozen us somehow.” She remembered the funeral, trudging up the hillside, the day wild with a ferocious wind, Gruen planting a tree on the grave. “It almost sent Leonora into hysterics,” she remarked, “the idea of those roots going down into Remedios’s grave.”

I met Leonora Carrington in her spartan home in the Chimalistac district of Mexico City where she had been living since the 1940s. She immediately put me at ease by discussing the new “corset” she had just bought at Price Choppers in Florida–it was the kind train porters use for a weak back. As I sat at the kitchen table where Dr. Stern had sat, she reminisced about those days in the early 1960s. “Pat had a wonderful eye, a very textured visual sense. She used egg-tempera with detailed precision. And she had a textured verbal sense, too.” Once I remember her sitting down toe a particularly unappetizing dish of rice and calling it ‘congealed blood.’ Nothing more needed to be said.”

But our talk soon took a higher note as we began to speak of Jung. “He was absolutely right about one thing,” Leonora said. “We are occupied by gods. The mistake is to identify with the god occupying you.” She, for instance, was possessed by Demeter, the mother, so obsessed was she with her two sons. “They are adult, have nothing to do with me, and yet I am still tied umbilically.” “Who occupies you?” she asked. When I said I did not know, she replied: “My guess would be Diana, the huntress. Identity is so mysterious. What, after all, are we? Identity is not the issue: our machine-mentation. I am. I am. I am. But is this so? The problem is not ego, but the mannequins. I have one for the gallery, one for each of my sons, one for my cat.” At one point I found myself talking about a novel by the Canadian, Timothy Findley, called Headhunter, about a woman who believes she has allowed an evil character to escape from a book. “Entities do enter our lives,” Leonora said. “One I experienced was malevolent. It has happened six or eight times since I was very young. It was a thing without shape or boundaries, amorphous. It comes as a sound. It was voracious, sucking, a sucking force and inside this entity were millions of other entities, equally voracious, crying desperately, one of which was me. As in hell.” “That sounds evil. What must evil be?” I asked. “An absence of attention. That is the only thing I can think of,” she replied. “The only thing we can do about evil is pay attention.” Such was a quiet afternoon with Leonora Carrington.

Leonora told me that the privilege of living in Mexico is that, in Mexico, the artist is free. In Anglo-Saxon countries the artist is suspect; at best a conversation piece, at least until fame brings wealth. Perhaps only in Mexico could the surrealist pleasure of friendship between these three women, so nurturing to their art, been so perfectly realized.

Tres figuras sexualmente ambiguas que parecen monjes están sentadas en torres almenadas. En cada habitación brilla una luz tenue; emana desde una fuente interior distinta. Una figura está pintando, otra escribiendo y la tercera bebe de una copa de vino. Cada una es independiente. Cada una ignora la existencia de la otra. Sin embargo, suspendido en el aire, un huso apenas visible conecta las tres figuras a una estrella lejana. La artista describe esto como “una complicada máquina de la que salen poleas que se enrrollan en ellos y los hacen moverse libremente (ellos creen moverse libremente)… [pero] el destino de esa gente sin ellos saberlo, está entrelazado, y algún día sus vidas se cruzarán y mezclarán”.

La artista es la gran pintora mexicano-española, Remedios Varo, y las tres vidas se cruzaron en su momento, atraídas como por sincronía para llevar a la realidad la narrativa de su pintura; tres mujeres que, de manera independiente, habían labrado la misma visión artística. Fue una reunión mágica la de P.K. Page, Remedios Varo y Leonora Carrington en México en 1960.

¿Cómo era esa amistad? Estamos tan acostumbrados al escenario tradicional de la joven artista bajo la tutela de un hombre artista de mayor edad. Cada una de estas mujeres había vivido esa clase de experiencia en su juventud cuando jugaban el rol de la musa al centro de un círculo artístico: Carrington y Varo en los círculos surrealistas de Francia, Page en el de los poetas del Preview en Montreal. ¿Cómo sería asomarnos dentro del proceso imaginativo de este fecundo intercambio cuando está ocurriendo plenamente en el contexto de la amistad femenina?

Page es una de las principales escritoras de Canadá: autora de más de una docena de poemarios; de una novela, The Sun and The Moon; de varios cuentos, uno de los cuales, Unless the Eye Catch Fire, ha sido llevado al teatro y a la pantalla; de un diario de viaje, Brazilian Journal; y de media docena de libros para niños. Pero bajo el nombre de P.K. Irwin, también fue pintora. Algunas de sus obras pueden verse en la Galería Nacional de Canadá.

Conocí a P.K. por primera vez en 1974; ella acababa de publicar su artículo “Traveler, Conjuror, Journeyman,” en el que describía el arte como algo mágico, su objetivo era el de alterar nuestra percepción de la realidad. Ella me adentró a las pinturas de Leonora Carrington y Remedios Varo y hablaba del tiempo que pasaron juntas en México. Intrigada por esa amistad, decidí viajar a México a buscarlas. La galería Arvil estaba presentando obras de Carrington y Varo para celebrar su 25º aniversario. Había visto esas pinturas en libros pero era la primera vez que las veía en persona. ¿Cómo describir su impacto sobre mí?

Las pinturas de Leonora Carrington tenían títulos como “Monopoteosis”, “Hierophant”, “Reflecciones en el oráculo” y “Penélope”. Parecían moverse en un torbellino de luz que jalaba al espectador hacia adentro y tuve una sensación de bouleversement en mi cabeza. Estaba viajando al interior de las pinturas atraída por una voluntad más fuerte que la mía. ¿Qué me decía la artista sobre la luz, el espacio y el tiempo? Junto a ella estaba otra creadora de mitos. Los lienzos de Varo estaban llenos de mecanismos alquímicos complicados; criaturas de cabezas invertidas y cuerpos de alambique; cabezas emergiendo de las paredes. Una de sus pinturas se llamaba “Los amantes”. Una pareja tomada de las manos, tenía rostros de espejos y se miraban fijamente a los ojos. Su atracción magnética era tan grande que levantó un remolino de vapor desde sus vestimentas azules para luego condensarse como el agua que ahogaba sus pies, y el espacio alrededor suyo era misterioso, negro y punteado con luz descendente. Esta mujer estaba contando historias que había vivido profundamente.

Varo había muerto en 1963 a los cincuenta y cinco años, pero tuve oportunidad de conocer a Leonora Carrington. Sus galerías de Nueva York y México se habían esforzado en desalentarme, insistiendo en que ahora ella rehusaba todas las entrevistas, pero el hecho de que yo estaba llevándole los saludos de Pat (así llamaba Leonora a P.K.) hizo que, amablemente y sin dudarlo, me invitara a visitarla. La descripción de su amistad fue tan encantadora como yo lo había esperado. Esta es la historia.

Cuando P.K. llegó a la ciudad de México en 1960 como la esposa del embajador de Canadá, tenía cuarenta y cuatro años y ya era un escritora exitosa. La residencia de la embajada en Montes Urales se llenó de artistas. Una noche, después de la cena, P.K. se vio relatando una extraña experiencia de su infancia. Su madre y ella estaban de pie mirando desde la ventana de la sala de su casa y de pronto se descubrieron mirando fijamente en los ojos de una criatura completamente aterradora que las vigilaba. “Parecía,” lo cuenta ahora, “como las descripciones actuales de los extraterrestres: ojos obscuros y redondos como discos, barbilla puntiaguda, estrecha y de cabellos lánguidos, suaves como los de un bebé, casi como si estuviera bajo el agua”. La criatura no era amenazante pero la asustó. Se volvió hacia su madre, quien también la había visto, y tranquilamente, su madre cerró la persiana. No sabía que entre la audiencia de esa noche estaba Leonora Carrington, quién se acercó a ella y le dijo: “Suena totalmente cierto”. Otros hubieran desestimado la historia como fantasía o excentricidad. Para Leonora, éstas eran cosas elementales pero tenían verosimilitud. Se volvieron amigas inmediatamente.

Carrington ya era famosa en México en aquella época. Había tenido una exposición individual que llenó la galería nacional de Bellas Artes y era venerada como la surrealista líder del país. P.K. la recuerda como una mujer alta y delgada, de ojos exquisitos. “Siempre dije que podría deslizarse por la grieta de la puerta, como si tuviera un dedo menos que nosotros en sus pies y manos; su físico era tan estrecho”.

En México, donde se ofrecía la ciudadanía y la ayuda a refugiados que el resto del mundo no aceptaba, Leonora conoció a Remedios Varo. Desde su llegada se hicieron amigas íntimas, encontrándose casi a diario, estudiando alquimia juntas e intercambiando sueños.

Hacia 1960, Remedios también era famosa. Había sido comisionada para hacer el mural del nuevo Pabellón de Cancerología del Centro Médico y sus pinturas se vendían bien. Todavía mantenía sus raíces surrealistas, escribiendo un ensayo en 1959 llamado De Homo Rodans, un tratado seudo-académico sobre los orígenes del hombre y del primer paraguas. Leonora y Remedios eran tratadas con cierta admiración, como dos genialidades excéntricas. Su comportamiento respondía al sentido lúdico que manejaban los antiguos surrealistas. Cuando Remedios organizaba una fiesta, buscaba en el directorio telefónico la sección de psiquiatras y llamaba al doctor tal o cual, retándolo a asistir. Las comidas que ella y Leonora preparaban eran famosas: por ejemplo, servían el arroz coloreado con tinta de calamar, como si fuera caviar.

Para mí, estas dos mujeres ofrecen un modelo de amistad femenina, rebelándose contra todo convencionalismo restrictivo y utilizando el humor como su arma predilecta. Cuando André Breton le pidió a Varo que participara en una exhibición de erotismo en 1959, ella describió cómo pretendía contribuir: “Un espíritu santo (paloma albina) de tres metros de alto, plumas reales (de pollos blancos, por ejemplo), con: nueve penes erectos (luminosos), treinta y nueve testículos con el sonido de campanitas navideñas, patas rosas… Házme saber, querido André, y te enviaré un dibujo exacto…” Le disgustaba el mito heroico del genio artístico, el gesto fastuoso: “Pintar es como hacer mermelada de fresa, hay que prepararla con mucho cuidado y bien”.

Cuando Leonora descubrió que P.K. podía hablar su lenguaje, inmediatamente la invitó a su estudio. En ese entonces, P.K. había progresado en su pintura del gouache al aceite, pero no estaba satisfecha con ese proceso. Leonora le insistió que tratara la pintura al temple, dándole su receta privada. Cuando P.K. le respondió que no sabía cómo usarla, Leonora contestó: “averigua”. P.K. desarrolló su propia técnica y de inmediato se sintió fascinada; se secaba tan rápido que podía tocarlo. “Ese era mi concepto de felicidad”.

En su versión propia de surrealismo, Leonora utilizaba de todo en beneficio de propósitos humorísticos o provocativos. Cuando P.K. entró en su estudio un día, la encontró trabajando en una “cosa”. Había encontrado unas tablas tiradas y las reacomodó, pintándolas de negro y haciéndoles hoyos. Encima de los hoyos había titulitos absurdos. “Metías los dedos dentro de los hoyos. En un uno de ellos había una tachuela del lado filoso, en otra crema de afeitar, en otra hollín,” explica P.K. “Se necesitaba valor para meter los dedos en esos agujeros. Te das cuenta cuan vulnerable es el dedo ciego. Los hombres mayores se rehusaban al experimento”.

P.K. recuerda sus encuentros a menudo divertidísimos, especialmente en una cena en la casa de Leonora, quien le había llamado esa mañana para quejarse de que la otra pareja invitada, insistía en traer con ellos a un tal Dr. Stern. Leonora siempre se incomodaba con gente cuya imaginación se quedaba “una octava muy por debajo”, y un extraño en su mesa le resultaba desconcertante. El único Stern que ella conocía era un urólogo mexicano. La cena transcurrió bastante respetable para los estándares de Leonora: el papel de baño y la catsup que generalmente agraciaban la mesa habían sido retirados. Retorciendo sus manos con ansiedad, Leonora lanzó una retahíla de preguntas sobre urología durante la cena, hasta que su invitado la interrumpió indignado: “Leonora, ¿sabes a quién tienes en tu mesa? Ni más ni menos que al violinista más grande del mundo, Isaac Stern”. La conversación pasó de manera un tanto incómoda al arte y alguien preguntó si a Stern le gustaba tocar para sí mismo. El respondió que sólo podía tocar para un público. Al preguntarle si podía entrar él solo en una habitación y tocar por puro gusto, él contestó que no. Tanto P.K como Leonora se horrorizaron. ¿Por qué pintan ustedes –preguntó él— si no para un público? P.K. recuerda que una de las dos respondió: “Para Dios, la cual fue una respuesta bastante pretenciosa pero quisimos decir que para nosotras mismas o quizá para un ser superior”. Isaac Stern replicó que cualquiera que dijera eso era un “mentiroso”. “Para entonces, ” P.K. explica, “yo tenía el vino tinto hasta el cogote, e indignada por su comentario, tomé mi copa y la arrojé hacia atrás. Salió volando por la ventana a mis espaldas y se fue a estrellar sobre el pavimento de la entrada”. Como respuesta retórica a la condescendencia del maestro, Leonora vio esto como una reacción genial. Al día siguiente, Leonora le envió a Stern un ramo de flores, diciéndole a P.K. que, aunque Stern no lo vería, había un mensaje en las flores. Cada flor tenía un significado.

En otra fiesta ofrecida por Kathleen Fenwick, curadora de dibujos y grabados de la Galería Nacional de Canadá, P.K. recuerda que una de las artistas invitadas era Remedios Varo. La columnista de sociales, Zena Cherry, apenas había vuelto de Italia, luciendo los zapatos de última moda. En lugar de tacones, los zapatos tenían ruedas fijas. Remedios estaba junto a ella. Por años les había estado pintando zapatos rodantes a sus figuras y estaba desesperada por obtener esos zapatos. Entre más cocteles bebía, se volvía más inoportuna, hasta que por fin, P.K. se volvió hacia Cherry y le dijo: “Ay, ya dale los malditos zapatos. ¿Qué no ves que los necesita?” Cherry, sin hacer gesto alguno, se fue se la fiesta.

Algo que tenían las tres mujeres en común era su interés en el espacio, el tiempo y otras dimensiones, así como en lo espirutual. Eran buscadoras. Hablaban sobre Jung, cuya obra leían juntas, sobre los niveles de conciencia, sobre cosas que parecían vitales y absolutamente esenciales. Una de las pinturas que hizo Remedios en esa época, llamada “Fenómeno de Ingravidez” sería utilizada más tarde por el físico Peter Bergman para la portada de su libro The Riddle of Gravitation. Trabajando de manera intuitiva, ella había comprendido el fenómeno con exactitud. También llevaban a cabo sus propios experimentos. P.K. recuerda a las tres desnudas, recostadas en la cama, posando sus respectivas manos sobre sus espaldas para determinar a qué distancia del cuerpo podían sentir la atracción del campo magnético.

Cada una era distinta: Remedios más alegórica, intelectual quizá, y fascinada por las disciplinas místicas: una de sus pinturas “Tránsito espiral” evoca la noción medieval de un rito iniciatorio o “el llamado”. Leonora explicaría que sus pinturas estaban basadas en visiones hipnagógicas, no en sueños. A un freudiano que una vez afirmó que no estaba adaptada, ella le respondió: “¿A qué?”. P.K. era la más verbal e interesada en la presión de la interioridad y en la idea de patrones simbólicos. En retrospectiva, describiría su tiempo en Latinoamérica. “Si Brasil era el día, México era la noche… La obscura noche mexicana me llevó de vuelta hacia mí misma y estaba asombrosamente conciente de las seis dimensiones del espacio”.

En 1962, Remedios Varo murió sorpresiva e inesperadamente de un ataque al corazón. “Todo se detuvo en un alto enceguecedor cuando ella murió”, dijo P.K. “Recuerdo que llamamos a su esposo Walter [Gruen] y había un círculo de sillas en la habitación. Walter no estaba allí. Nadie se conocía ni sabía cómo salir de esa habitación. Así que ahí nos sentamos. Era como si Remedios nos hubiera hecho eso, congelándonos de algún modo”. Recuerda el funeral, haber caminado la ladera con pesadez, el día enloquecido con un viento feroz, Gruen plantando un arbol en la tumba. “Hizo que Leonora casi cayera en La histeria de sólo pensar que esas raíces llegarían a la tumba de Remedios”.

Conocí a Leonora Carrington en su casa espartana de Chimalistac en la ciudad de México, donde ella había estado viviendo desde los 40´s. De inmediato me hizo sentir en casa cuando abordó el tema de su nuevo “corset” que recién había comprado en el Price Choppers de Florida. (Era como el que usan los maleteros en la estación de tren para la espalda). Mientras me sentaba en la mesa de la cocina, donde el Dr. Stern se había sentado, ella recordaba aquellos años a principios de los 60´s. “Pat tenía un ojo maravilloso, un sentido de la vista muy texturizado. Utilizaba el témpera con detallada precisión. Y también tenía un sentido verbal texturizado”.

Pero nuestra plática pronto subió una nota más alta cuando comenzamos a hablar de Jung. “Tenía toda la razón respecto a una cosa”, dijo Leonora. “Estamos habitados por dioses. El error está en identificarte con el dios que te habita”. Ella, por ejemplo, estaba poseída por Démeter, la madre; tan obsesionada estaba con sus dos hijos. “Ellos son adultos, nada tienen que ver conmigo y, sin embargo, aún estoy atada umbilicalmente”. “¿Quién te habita a ti?” me preguntó. Cuando le dije que no sabía, contestó: “Atinaría a decir que Diana, la cazadora”. Así transcurrió una tarde tranquila con Leonora Carrington.

Leonora me dijo que el privilegio de vivir en México es que, en México, el artista es libre. En países anglosajones, el artista es sospechoso; cuando mucho, un objeto de conversación, al menos hasta que la fama trae riqueza. Quizá sólo en México, el placer surrealista de la amistad entre estas tres mujeres, tan alimentada de su arte, pudo hacerse realidad.

Traducido al español por Wendolyn Lozano Tovar

Very nice read. Thank you!

But I don’t think Leonora Carrington lived in Chimalistac since the 1940s, as written. She lived in Roma Norte (Chihuahua 194). Maybe you are thinking of Elena Poniatowska, who lives in Chimalistac?