’68: The students, the president, and the CIA

El 68: Los estudiantes, el presidente y la CIA

Sergio Aguayo

English translation by Tanya Huntington

The following is an excerpt from Chapter One of the book of the same title, available online through Gandhi Publica.

The golden age began one Sunday in August, 1958. That morning, a breakfast meeting was held between the presidential candidate for the PRI, Adolfo López Mateos, and the CIA Station Chief in Mexico, Winston Scott. From that day forward, a collaboration developed that would become strategic following the triumph of the Cuban Revolution a few months later. Mexico became one of the main arenas of confrontation between the superpowers, and Scott occupied a privileged niche in the highest circles of Mexican political power. His access was so important that Washington left him in charge for thirteen years, when station chiefs are customarily relieved every four years.

The CIA Station in Mexico was considered by Washington to be “the best in WH [Western Hemisphere] and possibly one of the best in the Agency.” There were 50 U.S. agents stationed in Mexico, with 200 Mexicans as agents and informers. The jewel in the crown were the 14 agents of LITEMPO.

In 1960, Scott created the LITEMPO program, described by Anne Goodpasture —a CIA official who worked closely with Scott— as “a productive and effective relationship between CIA and select top officials in Mexico,” There were fourteen top-level officials In LITEMPO: three presidents (Adolfo López Mateos, Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, and Luis Echeverría Álvarez), two directors of the Federal Security Division (Fernando Gutiérrez Barrios and Miguel Nazar Haro) and possibly, the Chief of Díaz Ordaz’s Presidential General Staff (General Luis Gutiérrez Oropeza). The essential point here is that all of them were on the CIA payroll: they were paid agents of the CIA. The exact sum of their salaries is unknown.

We do know that when Díaz Ordaz was named presidential candidate, the CIA collaborated with his campaign by delivering “400 [dollars] per month as a subsidy from December 1963 to November 1964” This figure “was in addition to a regular salary of [deleted] per month paid to LITEMPO-1 as a station support agent”.

This rapport benefited both governments. The DFS helped the United States monitor and control the Cubans, the Soviets, and the disenchanted Americans and exiles who were passing through Mexico. The CIA corresponded by informing the president what the enemies of the regime were doing on a daily basis and if necessary, collaborating in their neutralization.

Instances of active CIA involvement in repression include the joint DFS-CIA operation against Víctor Rico Galán, a well-known, critical journalist in those years. According to Morley, “Win helped build the case against [Rico] Galan. In September 1966 he and twenty-eight associates were arrested.” The journalist was imprisoned in Lecumberri for seven years.

The relationship between Scott and Díaz Ordaz was so close that, according to Morley, in the sixties Winston Scott was the “second most powerful man in Mexico” after the president. Here are a few examples of his status: in December 1962, López Mateos and Díaz Ordaz signed their names as witnesses to Scott’s second wedding ceremony; in April 1964, Scott learned from the president that Díaz Ordaz was to be revealed as the PRI presidential candidate and in May 1969, Díaz Ordaz confided to him that he had hand-picked Luis Echeverría to become the next president of Mexico. He had vital pieces of information months ahead of the events.

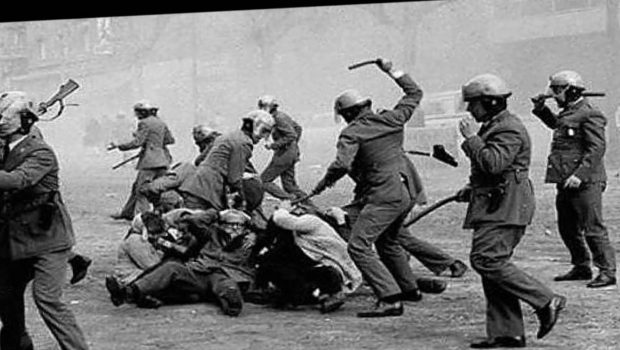

Scott and Díaz Ordaz were passionate anti-communists, and there is evidence that both the American and the Mexican contributed to the official narrative according to which the Movement of ’68 formed part of an international conspiracy assembled by the Soviets and the Cubans, among others. By transforming the Movement into an enemy of the fatherland, the president and the United States, they justified its repression. According to them, as well as other members of the upper echelons of power, the Mexicans largely responsible were Javier Barros Sierra, the president of the UNAM, and university professor Heberto Castillo.

After the night of Tlatelolco, Díaz Ordaz essayed an explanation that held the Movement responsible for the massacre: one that allows us to appreciate the intensity of his relationship with the CIA Station Chief. At that crucial moment, Scott defended the flimsy official story to his superiors in Washington and as a result, he lost credibility. An official from the United States Embassy in Mexico wrote that Scott presented “fifteen differing and sometimes flatly contradictory versions of what happened at Tlatelolco”. A few months later, they withdrew his appointment, adducing the excessive time he had spent in Mexico; in my opinion, Washington could no longer defend someone who had lost all objectivity.

These facts are related to a crucial aspect of our history that has been ignored: those aggressions against the population in which other governments knowingly participated. As a working hypothesis, it may be argued that the CIA was jointly responsible for the deaths and suffering caused on October 2, and that the same holds true for other Mexican tragedies. A similar argument may be made regarding the role played by Cuba and other international players during ’68. It is one of my long-term research goals to continue exploring this hypothesis.

Re-examining ’68 is also relevant in light of the crisis being experienced in Mexico today, in 2018. Fifty years have gone by and yet, the political elite continues to do everything in its power to prevent citizen participation in public affairs, despite the fact that a convergence between society and State seems to be the best way to confront criminal violence, government corruption, inequality, impunity and the hostility of Donald Trump and his followers.

Rethinking ’68 allows us to evoke a movement born out of the hope that a better Mexico is possible. Reliving that feat is one way to dispel uncertainty and discouragement: if it could be done then, we can do it now.

Sergio Aguayo Quezada is a full-time Professor at El Colegio de México since 1977. In 2014, he joined the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights of Harvard School of Public Health as a Research Associate. Aguayo has authored dozens of books and academic articles. He publishes a weekly syndicated column in the newspaper Reforma and since March 2001, he has appeared on Primer Plano, a weekly television program broadcast on Canal 11. Throughout his career, he has actively promoted democracy and human rights. His Twitter is @sergioaguayo

Sergio Aguayo Quezada is a full-time Professor at El Colegio de México since 1977. In 2014, he joined the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights of Harvard School of Public Health as a Research Associate. Aguayo has authored dozens of books and academic articles. He publishes a weekly syndicated column in the newspaper Reforma and since March 2001, he has appeared on Primer Plano, a weekly television program broadcast on Canal 11. Throughout his career, he has actively promoted democracy and human rights. His Twitter is @sergioaguayo

©LiteralPublishing

Este fragmento proviene del Capítulo Uno del libro del mismo título, disponible en línea a través de Gandhi Publica.

La etapa dorada se inició un domingo de agosto de 1958. Aquel día se reunieron a desayunar el candidato del PRI a la presidencia, Adolfo López Mateos, y el jefe de la Estación de la CIA en México, Winston Scott. A partir de ese momento se inició una colaboración que se volvería estratégica con el triunfo de la Revolución cubana, meses después. México se convirtió en una de las principales arenas de la confrontación entre las superpotencias y Scott ocupó un lugar privilegiado en los círculos más altos del poder político mexicano. Eran tan importantes sus accesos que Washington lo dejó 13 años en el cargo cuando lo habitual es que los jefes de Estación cambiaran cada cuatro.

La Estación de la CIA en México era considerada por Washington como “la mejor del Hemisferio Occidental y posiblemente una de las mejores” en el mundo. Tenía en México a 50 agentes estadounidenses y a 200 mexicanos como agentes e informantes. La joya de su corona eran los 14 agentes de LITEMPO.

En 1960, Scott creó el programa LITEMPO, descrito por Anne Goodpasture —funcionaria de la CIA que trabajó muy cerca de Scott– como una “relación productiva y efectiva entre la CIA y un selecto grupo de funcionarios mexicanos”. En LITEMPO estuvieron 14 funcionarios de alto nivel: tres presidentes (Ad olfo López Mateos, Gustavo Díaz Ordaz y Luis Echeverría Álvarez), dos directores de la Dirección Federal de Seguridad (Fernando Gutiérrez Barrios y Miguel Nazar Haro) y posiblemente el Jefe del Estado Mayor Presidencial de Díaz Ordaz (general Luis Gutiérrez Oropeza). Hay un punto bien importante: todos ellos estuvieron en la nómina de la CIA; fueron agentes pagados de la CIA. Se desconoce el monto exacto de los salarios.

Sí sabemos que cuando Díaz Ordaz fue nombrado candidato a la presidencia, la CIA colaboró con su campaña entregándole “400 dólares al mes” entre “diciembre de 1963 y noviembre de 1964”. Esta cifra complementaba el “salario regular de [número borrado] que se pagaba mensualmente a LITEMPO-1 [Díaz Ordaz] como agente de apoyo de la Estación” de la CIA.

La relación beneficiaba a los dos gobiernos. La DFS ayudaba a Estados Unidos a vigilar y controlar a cubanos, soviéticos y a los exiliados y estadounidenses desencantados que pasaban por México. La CIA correspondía informando cada día al presidente sobre lo que hacían los enemigos del régimen y, cuando era necesario, colaboraba en su neutralización.

Entre los casos de involucramiento activo de la CIA en la represión estaría la operación conjunta DFS-CIA contra Víctor Rico Galán, un periodista crítico muy conocido por aquellos años. Según Morley la CIA “ayudó a armar el caso y en septiembre de 1966 fueron detenidos [Rico Galán] y 28 asociados”. El periodista se pasaría siete años en Lecumberri.

La relación entre Scott y Díaz Ordaz era tan estrecha que, según Morley, “a mediados de los años sesenta”, el estadounidense Winston Scott era el “segundo hombre más poderoso de México”; después del presidente. Daré algunos ejemplos de este poder. En diciembre de 1962, López Mateos y Díaz Ordaz firmaron como testigos del segundo matrimonio civil de Scott. En abril de 1964 Scott fue informado por López Mateos que Díaz Ordaz era el “tapado” y en mayo de 1969 Díaz Ordaz le confió que había elegido a Luis Echeverría como el siguiente presidente de México.

Scott y Díaz Ordaz eran apasionados anticomunistas y hay evidencia de que el estadounidense y el mexicano contribuyeron al relato que transformó al Movimiento del 68 era parte de una conspiración internacional armada por soviéticos y cubanos, entre otros. Al convertirlo en enemigo de la patria, del presidente y de Estados Unidos justificaron su represión. Para ellos, y para los otros integrantes de la cúpula del poder, había los principales responsables mexicanos eran el rector de la UNAM, Javier Barros Sierra y el profesor Heberto Castillo.

Después de la noche de Tlatelolco, Díaz Ordaz improvisó una explicación para responsabilizar al Movimiento de la masacre que permite apreciar la intensidad de su relación con el jefe de la Estación de la CIA. En ese momento crucial, Scott defendió ante sus superiores en Washington la endeble historia oficial. Perdió su credibilidad. Un funcionario de la embajada de Estados Unidos en México escribió burlón que Scott presentó “15 versiones diferentes y a veces contradictorias sobre lo sucedido en Tlatelolco”. A los pocos meses lo retiraron del cargo aduciendo el excesivo tiempo que llevaba en México; en mi opinión, Washington no podía mantener a alguien que había perdido objetividad.

Estos hechos se relacionan con un aspecto ignorado en nuestra historia: las violaciones a garantías individuales en la cual participaron conscientemente otros gobiernos. Como hipótesis de trabajo puede argumentarse que al menos Winston Scott, y por omisión la CIA y el gobierno estadounidense, fueron corresponsable de las muertes y el sufrimiento causadas el 2 de octubre y que eso mismo ha sucedido en otras tragedias mexicanas. Un argumento parecido podría hacerse sobre el papel jugado por Cuba y otros actores internacionales durante el 68.

Revisar una vez más el 68 es también relevante por la crisis que vive México en 2018. Han transcurrido 50 años y las élites políticas siguen haciendo todo lo que está a su alcance para impedir la participación ciudadana en los asuntos públicos, aun cuando una convergencia entre sociedad y Estado sería la mejor forma de enfrentar la violencia criminal, la corrupción gubernamental, la desigualdad y la impunidad.

Repensar el 68 permite recordar un movimiento nacido por la esperanza de que es posible un México mejor. Revivir aquella gesta es una forma de ahuyentar el desconcierto y desaliento. Si se pudo entonces, podremos ahora.

Sergio Aguayo Quezada es profesor de tiempo completo de El Colegio de México desde 1977. A partir de 2014 se incorporó como investigador asociado del Centro FXB para la Salud y los Derechos Humanos de la Escuela de Salud Pública de Harvard. Ha escrito docenas de libros y artículos académicos. Publica una columna semanal en Reforma y desde marzo de 2001, participa en Primer Plano, programa de televisión semanal en Canal 11. Su Twitter es @sergioaguayo

Sergio Aguayo Quezada es profesor de tiempo completo de El Colegio de México desde 1977. A partir de 2014 se incorporó como investigador asociado del Centro FXB para la Salud y los Derechos Humanos de la Escuela de Salud Pública de Harvard. Ha escrito docenas de libros y artículos académicos. Publica una columna semanal en Reforma y desde marzo de 2001, participa en Primer Plano, programa de televisión semanal en Canal 11. Su Twitter es @sergioaguayo

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.