Austin Talk: Writers and Artists in the History of Mexico

Charla de Austin. Escritores y artistas en la historia de México

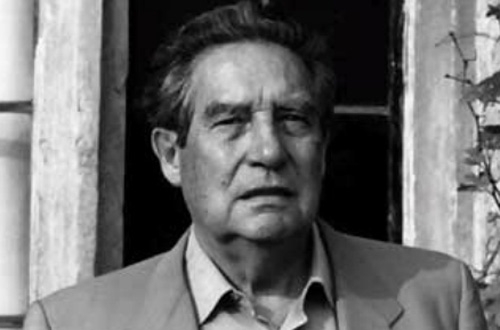

Octavio Paz

The topic of writers and artists in the history of Mexico is too broad and difficult to tackle in a short talk. My aim is actually much more modest. I intend to describe several features of what we may call the intellectual class in Mexican history. As I say this, I realize that the term may give rise to confusion. If we use the Marxist definition, classes are defined by their relation to the means and instruments of production. In that sense, intellectuals are not a class. However, I believe that they constitute a definite social group with very precise characteristics. The mandarins of China were intellectuals, for example; as were the clergy of medieval Europe, the humanists of the Renaissance, and the philosophers of the eighteenth century in France, England, and Germany. So we may use the term intellectual “class,” perhaps with a touch of skepticism, to refer to a group with its own interests and attitudes.

Now then, I am not going to concern myself here with the works of the intellectuals, remarkable though they may be. If Mexico has distinguished itself in anything, it has been in its major poetic and artistic creations. This is something too infrequently recognized: Mexican poetry has a very ample and precise tradition, from the pre-Columbian epoch up to our own time. Nor will I dwell on the works of our philosophers, some of them equally noteworthy. Instead, I will refer to the historical action of both groups, namely, to the attitudes of Mexican intellectuals toward modernity, an era which begins toward the end of the eighteenth century. Their moral and intellectual temper is important in relation to a decisive preoccupation in Mexico, and I daresay to the history of all Hispanic nations. In effect, in [Hispanic] America as in Europe, the central concern is modernization: how we can become modern. In our countries, this question was and is identified as the problem of democracy. From the end of the eighteenth century onward, in Spain no less than in Mexico or Argentina, how to be democratic means how to be modern. In general, we have understood modernity as republican democracy: we find in it a form of historical legitimacy distinct from the one that ruled us during the monarchy. Naturally, modernity is characterized among us by this zeal, one might say, for political and social democracy. In turn, the theme of independence, essential to the modernization of Mexico and Latin America, is linked to the theme of nationalism, a concern shared by liberals and conservatives alike.

Modernization as an issue appeared in the Hispanic world at the moment in which the peninsular elites discovered Spain’s relative backwardness. Spain had been an enormous European power in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and in some respects it was also a great center of culture. Nevertheless, by the middle of the eighteenth century it notices that not only has it fallen behind, but it has become that picturesque land that Europeans see as a corner of Europe, a place of superstitions and unjust privileges. We are talking about the age of Enlightenment, that is to say, about the beginnings of modernity throughout the world. It is also the period that will see the appearance of a certain type of ruler who, in all its variants, will be repeated at the European periphery: the enlightened despot (Catherine of Russia, Frederick of Prussia). Spain, for its part, had Carlos III, a despot who was not very despotic and was very enlightened. Reform began under his rule, with a critique of the Church and by importing enlightened ideas into Spain. Now there are two characteristics that should be pointed out. In the first place, it was not an ideology born in Spain but one adopted from France—with English influences as well. In the second place, it was a model destined to operate from the top down, with the backing of the monarchy, his ministers and intellectuals. I do not claim to examine the history of Spain here; but it must be emphasized that the efforts toward Enlightenment scarcely came to fruition. In that period Spain did not succeed in modernizing itself, owing to various historical circumstances; among them were the change of monarchs and, afterwards, the Napoleonic invasion. The entire nineteenth century would thus be a struggle for modernization, and it is only now, in the second half of the twentieth century, that Spaniards have become the first modern Hispanic nation.

Now I would like to deal exclusively with the case of modernization in Mexico, starting with the intellectual class because—here as elsewhere—they were the first agents of modernization. If we think of this culture in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, we find that the majority of Mexican intellectuals at the time were clergymen. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, [Carlos] Sigüenza y Góngora, the Jesuits, and . Motolinia [Fray Toribio de Benavente] were all members of the Church. They are a clerical class embedded within a closed system of orthodoxy. A world in which the ultimate truth is Revelation justified by a philosophy—scholasticism—and a society in which philosophical, artistic, and political issues are integrated within a totality. There is no pure artist: the artist is also a religious person. Sor Juana writes secular plays, love poems, and also religious mystery plays [autos sacramentales]. And her example can be taken as illustrative of the entire intelligentsia of New Spain [Nueva España]. So during the eighteenth century there existed in New Spain a group of Latinists, most of whom belonged to the Company of Jesus. They were part of a Church identified with the monarchy, with an empire on the defensive in the face of the threats from modernity that were represented by rival powers Holland, France, etc. Among them [i.e., the Jesuits], the spirit of crusade was fundamental. They are combatants for and defenders of the truth, having the character of intellectual warriors. On the one hand, they constitute a massive, established bureaucracy; at the same time, they are a combative bureaucracy, albeit one on the defensive. In effect, the Church and its clerics in New Spain were an immense political and intellectual fortress against the assaults of modernity, showing enormous merits in the field of art and pure thought, but closed off to history.

The European continent was living through a phenomenon that barely touched Spain, that of the Protestant Reformation, a movement of religious emancipation and critique. In the same way, a grand intellectual revolution was taking place during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In Spain there was no Descartes, no Newton; on the other hand, there were great theologians and poets. This phenomenon is decisive because Europe was then undergoing the only truly modern cultural revolution—a rather silly expression which we will use for convenience—a revolution which changed not only ideas but the morality and customs of the people. We usually pay attention to the critique of institutions carried out by Voltaire or to the examination of philosophical certitudes by Hume, but this period also saw a critique of the passions [emotions]. Thus the eighteenth century has two keywords that define it: Reason (men are rational, the truths of reason are eternal) and Passion (the passions are particular, but also subversive and revolutionary). So along with Hume and the great philosophers of the Enlightenment, one must also speak of the novelists, those who uncover the human passions, and among them the most devastating one, eroticism, sexuality. One thinks of [Pierre Choderlos de] Laclos or of the Marquis de Sade, for instance. All of this signified a change in the sensibility and behavior of people, the plurality of passions over against the universality of Reason. The diversity of opinions produced in turn a unique phenomenon, namely a tolerant society. And if Enlightenment wasn’t born in Spain but was adopted from France, as we have seen, the same was true elsewhere: neither in Spain nor here among us did this revolution of sensibility take place.

Modernization in Mexico began with the Jesuits. They were the educators of the native-born aristocracy of European descent, and were also the first to give shape to what we know as Mexican nationalism. Their attitude toward Enlightenment was always ambiguous, and they immediately clashed with enlightened Spanish authorities, that is, with the ministers and intellectuals under Carlos III. The expulsion of the Jesuits [in 1767] is a decisive chapter of our intellectual history because it meant that the Mexican aristocracy, and with it the intellectual class, would no longer have teachers and would have to invent itself. However, the triumph of liberals in the peninsula was what precipitated the independence of Mexico. And the day after Independence, the adoption of a democratic republic in imitation of the United States is consummated, but above all, a struggle is initiated between two groups: the liberals (or rather, supporters of local American traditions) versus the conservatives (who favored European traditions). This dispute will last throughout the nineteenth century as a struggle over the dilemmas posed by modernity. Whereas the liberals push for quick action, the conservatives prefer gradual change; while the latter defend Spanish traditions, the former attack them in favor of a blank slate with regard to the past. Nevertheless, what unites the two sides is intolerance, the incapacity for dialogue, thus giving rise to civil war.

The contenders in this war turned to foreign support, especially the conservatives (recall the chapter of Maximilian [Maximilian I, of Austrian-Hapsburg lineage, Emperor of Mexico 1864-67]), but also the liberals, who sought the backing of the United States. However, nothing was resolved by democratic means, and victory was decided by the fortune of arms. Never was the expression “Fortuna,” used by classical Latin authors, more appropriate. In the case of this war—like all wars, hazardous and never rational—the liberals won. A victory which, from 1860 up to our own days, suppressed the conservative side. Among the great political gaps in Mexico is the absence of a party of this kind. A serious problem, because it amounts to a mutilation of one part of a country’s tradition. I can say that in all honesty because I am not a conservative.

The victory of the liberals was transformed into the triumph of what Freud would call the Reality Principle. Instead of a democracy, we arrive at the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. This regime has been widely referred to as conservative, but the term is imprecise. It was rather a case of liberal enlightened despotism, a hybrid [mestiza] version of its European ancestor. The liberals were always federalists, in imitation of the United States. However, upon coming to power, they reaffirmed centralism and, instead of a rotation of power, Mexico experienced that dictatorship. As concerns the field of thought, Enlightenment liberalism—the official ideology of the regime—was replaced by pseudo-scientific positivism. We stopped worshipping Voltaire and Rousseau and turned to the effigies of [Auguste] Comte and Herbert Spencer. With Reason thus set aside, we venerated the telegraph and the microscope with a scientism tinged with a touch of absolutism. The Mexican intellectual class had changed ideas without renouncing its attitudes nor its deepest psychic structure.

Naturally, there were exceptions: Lucas Alamán among the conservatives, and among the liberals, Doctor [José María Luis] Mora. If positivism as an ideology wasn’t adequate to the national situation, it is also undeniable that [Francisco] Bulnes and Justo Sierra [Méndez] tried to adapt it in an effort to understand Mexican reality and history. But I repeat, they are isolated examples. The truth is that our intellectuals were heirs of an old theological class, enamored of generalizing explanations instead of observing our particularities. This disparity between modern ideas and pre-modern attitudes reveals a psychic split, a Latin American trait not yet studied. I imagine that the problem is to be found in the constitution of social forms. When these don’t change, it hardly matters that ideas mutate. The most profound social form is the family, insofar as the ideas of authority, property, morality, respect for and attitude toward others are all born in it. It is possible that there lies the cause of the disparity between the philosophy of the Mexican intellectual class and its attitudes: a pre-modern psyche embedded in a modern ideology. How can a nation modernize itself when those in charge of it are not entirely modern? That is the question that I have been asking myself for many years.

By the end of the Porfirio Díaz regime [1876-1911], the intellectual class found itself wholly integrated into the government, with a few exceptions among the younger generation. Nevertheless, the dictatorship was an immovable regime, and the Revolution broke out, an episode in which the majority of intellectuals did not take part. It was rather a spontaneous and popular uprising, that is, of peasants and ranchers with the participation of several workers’ groups organized by their leaders (one way or another, the working class was always mediated by politicians). The interesting thing is that one could count on the fingers of one hand the number of first-rank intellectuals who were revolutionaries: [José] Vasconcelos, Martín Luis Guzmán, and three or four others. The rest of the luminaries stayed on the sidelines. Chaos was unleashed by the Revolution, and in that great chaos, the country sought and found itself. One of the interesting things to be noticed at that moment was how the intellectuals of the old regime responded to the call of Revolution—excepting those who were either very committed to Huerta [José Victoriano Huerta Márquez] or involved in other conservative episodes. The majority of them returned to government and formed part, for example, of the higher echelons of diplomacy, the treasury, or education. It is worth recalling that in this last group, there was a minister of intellectual genius: Vasconcelos. It was he who initiated a grand cultural movement, creating a new Mexican intellectual class, one also profoundly integrated into the State.

This phenomenon of assimilation accelerated around the middle of the twentieth century, when the revolutionary regime passed from the rule of military strongmen to that of civilian presidents, thanks to a political creation that was useful at its origin but is at present harmful: the hegemonic party, PRI [Institutional Revolutionary Party, 1929-1990s]. The type of intellectual who has been integrated into the political bureaucracy holds modern cultural values, and is trained in such questionable fields as sociology or economics. For my part, I prefer the humanistic disciplines, those that are frankly non-scientific or that border on scientific only in certain aspects, like history; or disciplines with scientific intent but conscious of their limitations, like anthropology. The sciences that offer global explanations, like sociology, terrify me, especially when I see they were founded by the great Auguste Comte, who invented the religion of humanity and other dangerous chimeras. This class of intellectual, as I was saying, has been fundamental in the modernization of culture in Mexico, and we owe many positive things to it. Nonetheless, we must accept that it was never democratic: interested only in solving social problems, it always operated from a position of power. Somehow and for the most part, they thought that social problems could be solved by decree, from above or through education. They thus reproduced the enlightened despotism of Carlos III: an intellectual attitude distrustful of particularity and placing great hopes in philanthropic action directed from above.

In sum, the intellectuals not only became collaborators with the State but also advisors of a sort to the new rulers. A minority has been radical or revolutionary; influenced by Marxism, it believes in violent organized action. For example, an undemocratic group that collaborated with the government during the Lombardo Toledano period. In other cases, this type of intellectual has remained independent from the State, but not from its own international models. Almost all of these were profoundly Stalinists and, later, admirers of Fidel Castro and of the worst aspects of Castroism. A phenomenon mentioned earlier becomes even more pronounced around this time. There is no conservative ideology in Mexico, we said, although there are conservative interests. Let me emphasize that I am not referring to these, but to an ideology. On the other hand, referring to the opposing side, if there were liberal intellectuals around that time, they were always an exception. Here I mean liberals in the older sense, not in the modern one as used in the United States, because, I think, the liberals of this country are in reality social democrats. I refer to intellectuals like [Daniel] Cosío Villegas and others whom I won’t mention because they are close to me—and I am one of them.

Among the great modern problems of Mexico, an essential one is the demographic problem of excessive population growth. There has been no study of that by our intellectual class that emerged from the Revolution. Perhaps it seemed to them that the topic wasn’t modern: Marx had already described it. Then there is the backwardness of patrimonialism, which is to say, of corruption. This is not only a moral issue—there is corruption in all regimes, not only in Mexico—but it is one that has its roots in concrete social reality. Patrimonialism was studied by Machiavelli, and later by Max Weber, but it would be futile to look for a good study of this problem by our intellectuals. Or take the issue of political bureaucracy. Only a few of us dissident thinkers [heterodoxos] have insisted on pointing out how this problem—certainly a universal phenomenon—takes on special characteristics in Mexico, where the imbrication of bureaucracy and political power is more profound than elsewhere, to such a degree that one can speak of a political-bureaucratic class. One also doesn’t hear much about centralism, another fundamental issue. Mexico City is a monster, but why? It has not been so by a demographic accident, but by a political one. It has flourished because it is a mirror of Mexican centralism, going back to the pre-Columbian period. One would have to reformulate the need for a reexamination of centralism, similar to the one undertaken by liberals like [Benito] Juárez in their day. The fundamental thing would have been to do a critique of centralism by way of returning to federalism, but no one did this … the contribution of this [intellectual] class to such a criticism has been small. On the other hand, if we think of its constructive activities, as in education, in legislation, etc., its contributions have been immense. Its impact has been profoundly positive, though always part of the system, never critical of it. When they have tried to be critical, it hasn’t been in a concrete manner but rather by means of general ideas. The criticism was always ideological, never practical.

In recent years, the economic crisis in Mexico has shown the reality of our country. It is a financial, economic problem, but above all a political and moral one. It is clear that many of the errors committed in the past (to give examples: corruption, the taste for excessive planning, illusions about the petroleum bonanza) are owing to the lack of political controls. In this sense, it is undeniable that the Mexican state lacks the necessary division of powers: the influence of a more critical and less ideological press does not exist; there is no autonomous legislative body, and, finally, we lack an authentic democracy. The road to modernization—in this, the revolutionaries of the eighteenth century, the liberals of the nineteenth, and [Francisco Ignacio] Madero were not mistaken—must pass through political reform, and this must pass through democracy. Without it there can be no economic or social reform.

Of course, the government won’t accomplish this alone. And it won’t do so because no one in history has done so. To put it another way, the governing classes change when obliged to change by violence or circumstances. I am one who believes in gradual and peaceful changes. That’s why I speak: I believe in the power of language. Gradual and peaceful modifications are not achieved without the intellectual class. Not because this class possesses the power to change things, but because it exerts a power of persuasion that other classes do not have. That is why a change of consciousness is fundamental. If we observe the attitude of many radical groups in Mexico, it is only now that they accept the necessity of democracy. The Mexican intellectual class should carry out a self-criticism of its past and of its most recent attitudes, repudiating its ideological idolatries, and learning tolerance. Also indispensable is a critical examination of our idea of modernization, an organic criticism, one that takes its cues from the people.

Not long ago, Mexico experienced something that was at once atrocious and (if one may call it that) marvelous. When the earthquake struck [Mexico City, 1985], I was there and was impressed with how, in such catastrophes produced by chance, we become accomplices of the latter. The newer buildings fell down, not the older ones. In some basic way the earthquake was not only geological or natural but also moral, political, and historical. Along with that I observed the reaction of the people: they organized themselves and worked together in a way that provided a lesson in true democracy. Now the word democracy has been so over-used that it’s sometimes annoying. More ancient is the word fraternity, brotherhood among men. Everyone got together and reached agreement: they picked up their dead and rescued the living by means of spontaneous collective action. From its beginnings, to be sure, humanity has had to deal with nature, our mother and stepmother. But I would say that on this occasion, I witnessed an ancestral response of the people: I discovered the spirit of fraternity embedded in the Mexican tradition.

When I returned to Mexico in the 1960s, my friends and I founded Plural. A literary journal, because we are not politicians, we are writers who don’t believe that writing should be in the service of anything. However, we understand that those who write need to say what they think about the political reality. That is why we called it Plural: a pluralistic and particular vision, diversity versus a homogeneous vision of society. There are no universal truths, there are partial and particular truths. That publication disappeared, and we took refuge in Vuelta, an independent literary journal in which we also published articles by political thinkers. Vuelta sets the tone for what one would like to see in the Mexican intellectual class, pluralistic and tolerant of others; a second turn capable of going back and recovering the tradition. The road to modernity passes through the re-conquest of this tradition.

El tema de los escritores y artistas en la historia de México es demasiado amplio, difícil de abordar en una plática breve. Mi propósito en realidad es mucho más modesto. Me propongo describir algunos rasgos de lo que llamaríamos la clase intelectual en la historia de México. Cuando digo esto me doy cuenta de que el término puede prestarse a confusión. Si usamos la definición marxista, las clases se definen por la relación con sus instrumentos y medios de producción. En ese sentido los intelectuales no son una clase. Sin embargo, creo que constituyen un grupo social definido y con características muy precisas. Fueron intelectuales los mandarines de China, por ejemplo; asimismo, los clérigos de Europa en la Edad Media, los humanistas del Renacimiento y los filósofos del siglo XVIII en Francia, Inglaterra y Alemania. De modo que podemos usar el término de “clase” intelectual, con un poco de escepticismo quizá, para referirnos a un grupo con intereses y actitudes propias.

Ahora bien, no voy a ocuparme aquí de las obras de los intelectuales, aunque algunas sean muy notables. Si México ha destacado en algo, ha sido en sus grandes creaciones poéticas y artísticas. Se trata de algo pocas veces reconocido: la poesía mexicana tiene una tradición muy amplia y precisa, desde la época precolombina hasta nuestros días. Tampoco me detendré en la obra de nuestros pensadores, algunas también notables. En cambio, me referiré a la acción histórica de ambos, es decir, a las actitudes de los intelectuales mexicanos hacia la modernidad, época que inicia a finales del siglo XVIII. Dicho temple intelectual y moral es importante en relación con una preocupación decisiva en México y, me atrevería a decir, de la historia de todos los pueblos hispánicos. En efecto, lo mismo en América que en Europa, el tema central es la modernización: cómo podemos llegar a ser modernos. En nuestros países esta modernización estuvo y está identificada con el problema de la democracia. Desde fines del siglo XVIII y lo mismo en España que en México o Argentina, cómo ser democráticos quiere decir cómo ser modernos. En general, hemos entendido la modernidad como democracia republicana: encontramos en ella una forma de legitimidad histórica distinta de la que nos rigió durante la monarquía. Naturalmente, la modernidad se distingue entre nosotros por este afán, diríamos, de democracia política y social. Por su parte, el tema de la Independencia, esencial en la modernización de México y América Latina, está ligado al del nacionalismo, preocupación que compartieron liberales y conservadores.

La modernización como tema apareció en el mundo hispánico en el momento en que las elites peninsulares descubrieron sus rezagos. España había constituido un enorme poder europeo en los siglos XVI y XVII y, en ciertos aspectos, fue también un gran centro de cultura. Sin embargo, a mediados del XVIII advierte que no sólo se ha quedado atrás sino que se ha convertido en esa tierra pintoresca que los europeos ven como un rincón de Europa, lugar de la superstición y los privilegios injustos. Estamos hablando de la época de la Ilustración, es decir, del comienzo de la modernidad en todo el mundo. Un período también que verá aparecer a cierto tipo de gobernante que, con sus variantes, se repetirá en la periferia: el déspota ilustrado (Catalina de Rusia, Federico de Prusia). España, por su parte, tuvo a Carlos III, un déspota poco despótico y muy ilustrado. Con él se inicia la reforma mediante una crítica de la Iglesia y llevando las ideas de la Ilustración a España. Ahora bien, hay dos características aquí que debemos señalar. En primer lugar, no se trata de una ideología nacida en la Península sino adoptada de Francia –y de influencia inglesa también–. En segundo lugar, se trató de un modelo destinado a operar desde arriba, con el respaldo de la monarquía, de sus ministros e intelectuales. No pretendo examinar la historia de España, sin embargo, es necesario destacar que las tentativas de la Ilustración apenas si se realizaron. La España de entonces no logró modernizarse por varias circunstancias históricas; entre ellas, hubo un cambio de monarquía y, después, sobrevino la invasión napoleónica. Todo el siglo XIX será así una lucha por la modernización y sólo hasta ahora, en la segunda mitad del siglo XX, los españoles son el primer pueblo hispánico moderno.

Ahora quisiera referirme exclusivamente al caso de la modernización en México partiendo de la clase intelectual porque sus primeros agentes –como en cualquier parte– fueron los intelectuales. Si pensamos en la cultura en los siglos XVI, XVII y XVIII, encontraremos que la mayoría de los intelectuales mexicanos en esa época eran clérigos. Formaban parte de la Iglesia sor Juana Inés de la Cruz y Sigüenza y Góngora, los jesuitas o Motolinía. Son una clase clerical inserta dentro del sistema cerrado de una ortodoxia. Un mundo donde la verdad última es la revelación justificada por una filosofía: la escolástica, y una sociedad en donde los temas filosóficos, artísticos y políticos están integrados a una totalidad. No hay artista puro: el artista es un religioso también. Sor Juana escribe comedias, poemas de amor y autos sacramentales. Y el de ella es un ejemplo que puede ilustrar a toda la inteligencia novohispana. Así, durante el siglo XVIII existía en Nueva España un grupo de latinistas pertenecientes en su mayoría a la compañía de Jesús. Formaban parte de una Iglesia identificada con la monarquía, con un imperio a la defensiva ante las amenazas de la modernidad representada por las potencias rivales, Holanda, Francia, etc. Entre ellos el espíritu de cruzada resultaba fundamental. Son combatientes y defensores de la verdad, con carácter de guerreros intelectuales. Por un lado constituyen una inmensa burocracia establecida, asimismo, representan a una burocracia combatiente aunque a la defensiva. En efecto, la Iglesia y sus clérigos en Nueva España fueron una inmensa fortaleza intelectual y política contra los asaltos de la modernidad, con méritos enormes en el campo del arte y el pensamiento puro, pero cerrada a la historia.

El continente europeo estaba viviendo un fenómeno que apenas si toca a España, el de la Reforma protestante, movimiento de emancipación y crítica religiosa. Del mismo modo, se llevaba a cabo una gran revolución intelectual durante los siglos XVII y XVIII. En España no hubo ningún Descartes, ningún Newton; en cambio, tuvo grandes teólogos y poetas. Este fenómeno es determinante porque Europa experimentaba entonces la única revolución verdaderamente cultural moderna –expresión bastante tonta que emplearemos por comodidad–, una revolución que cambió no sólo las ideas sino la moral, las costumbres de la gente. Usualmente reparamos en la crítica de las instituciones efectuada por Voltaire o el examen de las certidumbres filosóficas de Hume, pero en esa época se dio también una crítica de las pasiones. El siglo XVIII tiene así dos grandes palabras que lo definen: Razón (los hombres son racionales, las verdades de la razón son eternas) y Pasión (las pasiones son particulares, pero también subversivas y revolucionarias). De modo que a lado de Hume y los grandes filósofos de la Ilustración, habría que hablar también de los novelistas, de aquellos que descubren las pasiones humanas y, entre éstas, a la más devastadora: el erotismo, la sexualidad. Hablamos de Laclos o del Marqués de Sade, por ejemplo. Todo esto significó un cambio de la sensibilidad y la conducta de la gente, la pluralidad de pasiones frente a la universalidad de la Razón. La diversidad de las opiniones produjo por su parte un fenómeno único, el de una sociedad tolerante. Y si la Ilustración no nació en España sino que fue adoptada de Francia, según hemos visto, lo mismo pasó en otras partes: ni en España ni entre nosotros sucedió esta revolución de la intimidad.

La modernización en México comienza con los jesuitas. Fueron ellos los educadores de la aristocracia criolla mexicana y, asimismo, los primeros en darle forma a lo que conocemos como nacionalismo mexicano. Su actitud frente a la Ilustración siempre fue ambigua e inmediatamente chocaron con las autoridades españolas ilustradas, es decir, con los ministros e intelectuales de Carlos III. La expulsión de los jesuitas es un capítulo decisivo en nuestra historia intelectual porque significó que la aristocracia mexicana, y con ellos la clase intelectual, dejará de tener maestros y se hará a sí misma. Sin embargo, el triunfo de los liberales en la Península fue el que precipitó la Independencia de México. Y al otro día de la Independencia se consuma en México la adopción de una república democrática a imitación de Estados Unidos pero, sobretodo, se desata una lucha entre dos bandos: liberales (más bien partidarios de los americanos) contra conservadores (afines a las tradiciones europeas). Esta disputa se prolongará a lo largo de todo el siglo XIX como una lucha determinada por los dilemas de la modernidad. Mientras que los liberales impulsan una acción rápida, los conservadores se inclinan por un cambio paulatino; estos defienden las tradiciones hispánicas, aquellos las atacan en nombre de una tabla rasa sobre el pasado. Sin embargo, a ambos los une la intolerancia, su incapacidad para dialogar. Se trata de partidos cerrados y con ideologías totales cuyos enfrentamientos desconocen la lucha democrática, dando lugar así a la guerra civil.

En esta guerra los contendientes acudieron al apoyo extranjero, en especial los conservadores (recordemos el capítulo de Maximiliano), aunque también los liberales buscaron el respaldo de Estados Unidos. Sin embargo, nada se resolvió en términos democráticos y no fue sino la fortuna de las armas la que decidió la victoria. Nunca fue más exacta la expresión de los clásicos latinos cuando se refieren a la Fortuna, el accidente. En el caso de esta guerra –como todas, siempre azarosa y nunca racional– vencieron los liberales. Un triunfo que desde 1860 y hasta nuestros días, suprimió al partido conservador. Entre los grandes vacíos políticos de México se encuentra la ausencia de un partido de esta naturaleza. Realidad grave porque es mutilar a un país de una parte de su tradición. Lo puedo decir con toda honradez porque no soy conservador.

La victoria de los liberales se transformó en el triunfo de lo que Freud llamaría el principio de realidad. En lugar de una democracia, arribamos a la dictadura de Porfirio Díaz. Se ha hablado mucho de ésta como de un régimen conservador pero el término es inexacto. Se trató más bien de un despotismo liberal ilustrado, versión mestiza de su antecedente europeo. Los liberales siempre fueron federalistas, a imitación de Estados Unidos, sin embargo, cuando accedieron al poder reafirmaron el centralismo y, en vez de una alternancia, México vivió aquella dictadura. Por lo que toca al terreno del pensamiento, el liberalismo de la Ilustración –corriente oficial del régimen– fue sustituido por la filosofía seudo científica del positivismo. Dejamos de adorar a Voltaire y Rousseau ante las efigies de Comte y Herbert Spencer. Suplantada así la Razón, veneramos al telégrafo y al microscopio con un cientismo teñido de gusto absolutista. La clase intelectual mexicana había cambiado de ideas sin renunciar a sus actitudes ni a su forma psíquica más profunda.

Naturalmente, hubo excepciones: Lucas Alamán entre los conservadores y, entre los liberales, el doctor Mora. Si el positivismo como ideología no se adecuaba a la situación nacional, es innegable también que Bulnes y Justo Sierra trataron de adaptarlo para entender la realidad mexicana y su historia. Pero, repito, se trata de ejemplos aislados. La realidad es que nuestros intelectuales fueron herederos de una vieja clase teológica, enamorados de las explicaciones globales en lugar de observar nuestras particularidades. Esta disparidad entre ideas modernas y actitudes premodernas delata una escisión psíquica, una característica de lo latinoamericano aún no estudiada. Imagino que el problema se encuentra dentro de la constitución de las formas sociales. Cuando éstas no cambian, apenas si importa que muden de ideas. La forma social más profunda es la familia en la medida que las ideas de autoridad, propiedad, moral, respeto y actitud frente a los otros, nacen en ella. Es posible que allí se ubique la razón de la disparidad entre la filosofía de la clase intelectual mexicana y sus actitudes: una psiquis premoderna incrustada en una ideología moderna. ¿Cómo se puede modernizar a una nación si los responsables no son enteramente modernos? Esta es la pregunta que me hago sin cesar desde hace muchos años.

Al final del porfiriato la clase intelectual se encontraba totalmente integrada al régimen, con excepciones entre los jóvenes. No obstante, la dictadura porfirista era ya un régimen inamovible y estalla la Revolución, episodio en el que la mayoría de los intelectuales no participó. Se trató más bien de un levantamiento espontáneo y popular, es decir, de campesinos y rancheros con la participación de algunos grupos obreros organizados por sus líderes (de un modo o de otro, la clase obrera siempre fue mediatizada por los políticos). Lo interesante es que se pueden contar con los dedos de la mano a aquellos intelectuales de primer orden que fueron revolucionarios: Vasconcelos, Martín Luis Guzmán y otros tres o cuatro más. El resto de las luminarias se mantuvo al margen. Con la Revolución se desató el caos y, en ese gran caos, el país se buscó y encontró a sí mismo. Uno de los rasgos interesantes en ese momento fue ver cómo los intelectuales del viejo régimen acudieron al llamado de la Revolución –excepto los muy comprometidos con Huerta o con otros episodios conservadores–. La mayoría regresó al gobierno y formó parte, por ejemplo, de la alta diplomacia, de hacienda y educación. Vale recordar que en ésta hubo un ministro de genio intelectual: Vasconcelos. Fue él quien dio inicio a un gran movimiento cultural, creando a una clase intelectual mexicana nueva, también profundamente integrada al Estado.

Dicho fenómeno de asimilación se aceleró en la mitad del siglo XX, cuando el régimen revolucionario pasó del dominio de los caudillos militares al de los presidentes civiles gracias a una creación política útil en su origen pero que ahora resulta nociva: el partido hegemónico, PRI. La clase de intelectual integrado a la burocracia política ha sido gente de cultura moderna, técnicos en materias quizá dudosas como la sociología o la economía. Por mi parte, prefiero las disciplinas humanísticas, francamente no ciencias o que colindan con éstas sólo en algunos aspectos, como la historia; o bien disciplinas con intención científica pero conscientes de sus limitaciones, como la antropología. Las ciencias que tratan de dar explicaciones globales como la sociología me dan terror, especialmente cuando veo que fueron fundadas por el gran Augusto Comte, aquél que inventó la religión de la humanidad y otras peligrosas quimeras. Esta clase de intelectual, decía, ha sido fundamental en la modernización de la cultura de México y le debemos muchas cosas positivas. Sin embargo, debemos aceptar que no fue democrática: interesada en resolver los problemas sociales, siempre quiso actuar desde el poder. De alguna manera y en su gran mayoría, pensaban que los problemas sociales se resolverían por decreto, desde el poder o a través de la educación. Reproducían así el despotismo ilustrado de Carlos III: una actitud intelectual desconfiada de lo particular y con una gran esperanza en la acción filantrópica realizada desde arriba.

En suma, los intelectuales no sólo se convirtieron en colaboradores del Estado sino en una suerte de consejeros de los nuevos príncipes. Una minoría de ellos ha sido radical y revolucionaria; influida por el marxismo, cree en la acción violenta y organizada. Un grupo no democrático que colaboró con el gobierno en la época de Lombardo Toledano, por ejemplo. En otros casos, este tipo de intelectuales se ha mantenido independiente del Estado pero no de sus modelos internacionales. Casi todos fueron profundamente estalinistas y, posteriormente, admiradores de Castro y de los peores aspectos del castrismo. Otro fenómeno mencionado antes se acentúa aún más por estas fechas. No hay en México una ideología conservadora, dijimos, aunque sí intereses conservadores. Subrayo que no estoy hablando de estos sino de una ideología. Por otro lado y refiriéndonos a su contraparte, si han existido intelectuales liberales en estas fechas han sido siempre una excepción. Liberales en el viejo sentido, no en el moderno de Estados Unidos porque, creo, los liberales de este país en realidad son social-demócratas. Hablo de intelectuales como Cosío Villegas y otros que no mencionaré porque están cerca de mí –y yo soy uno de ellos.

Entre todos los grandes problemas modernos de México, uno esencial es el de la demografía, el crecimiento excesivo de la población. No hay ningún estudio al respecto por parte de nuestra clase intelectual surgida de la revolución. Quizá les pareció que el tema no era moderno: ya Marx lo había descrito. O bien los rezagos del patrimonialismo, es decir, de la corrupción. Tema no simplemente moral –no es que haya sólo en México, en todos lados hay corrupción– sino que nace de una realidad social concreta. El patrimonialismo ha sido estudiado por Maquiavelo y, después, por Marx Weber, pero sería inútil buscar un buen trabajo de nuestros intelectuales acerca del tema. O bien el asunto de la burocracia política. Somos unos cuántos heterodoxos los que insistimos en señalar cómo el problema –fenómeno universal ciertamente– en México adquiere características especiales ya que la imbricación entre burocracia y poder político es más profunda, al grado de que se puede hablar de una clase política-burocrática. Tampoco se habla del centralismo, tema fundamental también. La ciudad de México es un monstruo, pero ¿por qué? No ha sido por un accidente demográfico, sino por uno de tipo político. Ha florecido porque es el espejo del centralismo mexicano, que viene desde la época precolombina. Habría que replantear entonces la necesidad de un examen del centralismo, similar al que en su momento hicieron liberales como Juárez. Lo fundamental hubiera sido una crítica del centralismo mexicano para volver al federalismo, pero nadie lo hizo… La contribución de esta clase a la crítica es poca. En cambio, si pensamos en sus actividades del tipo constructivo, en la educación, en la legislación, etc., sus aportaciones son inmensas. Esto ha sido profundamente positivo, aunque integrado siempre al sistema y nunca crítico. Cuando lo han intentado no ha sido de modo concreto sino utilizando ideas generales. La crítica ha sido siempre ideológica, nunca práctica.

En los últimos años, la crisis económica de México ha mostrado la realidad de nuestro país. Se trata de un problema financiero, económico pero, sobretodo, político y moral. Resulta evidente que parte de los errores cometidos en el pasado (por dar ejemplos: la corrupción o el gusto por la planificación excesiva, el espejismo frente a la bonanza petrolera), se debe a la falta de controles políticos. En este sentido, es innegable que el Estado en México no tiene la necesaria división de poderes: no existe la influencia de una prensa más crítica y menos ideológica; no hay un poder legislativo autónomo y, finalmente, carecemos de una auténtica democracia. El camino de la modernización –no estaban equivocados los revolucionados del siglo XVIII, los liberales del siglo XIX o Madero–, pasa por la reforma política y ésta por la democracia. Sin ella no puede haber reforma económica ni social.

Por supuesto, el régimen no lo hará solo. Y no lo hará porque ninguno en la historia lo ha hecho así. Para reformularse, las clases gobernantes cambian obligadas por la violencia o por las circunstancias. Yo soy de los que creen en los cambios graduales y pacíficos. Por eso hablo: creo en la palabra. Las modificaciones graduales y pacíficas no se consiguen sin la clase intelectual. No porque ésta sea dueña del poder de cambiar algo sino porque ejerce una capacidad de persuasión que no tienen otras clases. De allí que sea fundamental un cambio en la conciencia. Si observamos la actitud de muchos grupos radicales en México, no ha sido sino hasta ahora que aceptan la necesidad de la democracia. La clase intelectual mexicana debe efectuar una autocrítica de su pasado y de sus actitudes más recientes: repudio de sus idolatrías ideológicas, aprendizaje de la tolerancia. Asimismo, es indispensable un examen de nuestra idea de modernización, una crítica orgánica e inspirada en lo popular.

Hace poco México vivió un fenómeno atroz y al mismo tiempo (si puede decirse) maravilloso. Cuando ocurrió el terremoto yo estaba allí y me impresionó advertir cómo en las catástrofes producto del azar nos volvemos cómplices de éste. Los edificios nuevos se desplomaron, no los antiguos. De algún modo la raíz del terremoto no fue sólo geológica ni natural, sino también moral, política e histórica. Junto con ello observamos la reacción de la gente: se organizó de forma espontánea y trabajó dando una lección de lo que es una verdadera democracia. Ahora bien, la palabra democracia se ha usado tanto que a veces resulta fastidiosa. Más antigua es la palabra fraternidad, hermandad entre los hombres. Todos se reunieron y pusieron de acuerdo: levantaron a sus muertos y rescataron a los vivos mediante una acción colectiva espontánea. Desde sus orígenes, es cierto, la humanidad ha tenido que enfrentarse a la naturaleza, nuestra madre y nuestra madrastra. Pero debo decir que en esta ocasión advertí una ancestral reacción popular: descubrí la fraternidad inserta en la tradición mexicana.

Cuando regresé a México en los años setenta, mis amigos y yo fundamos Plural. Una revista literaria porque nosotros no somos políticos, somos escritores que no creen que la escritura deba estar al servicio de nada. Sin embargo, entendemos que quienes escriben tienen la necesidad de decir lo que piensan sobre la realidad política. De allí que la hayamos nombrado Plural: visión pluralista y particular, diversidad frente a una visión homogénea de la sociedad. No hay verdades universales, hay verdades parciales y particulares. Esa publicación desapareció y nos refugiamos en Vuelta, revista literaria independiente en donde también publicamos artículos de políticos. Vuelta da la tónica de lo que quisiera en la clase intelectual mexicana, pluralista y tolerante con los otros: segunda vuelta capaz de volver y recoger la tradición. El camino de la modernidad pasa por la reconquista de esta tradición.