On Alternatives to Idealism

Alternativas contra el idealismo

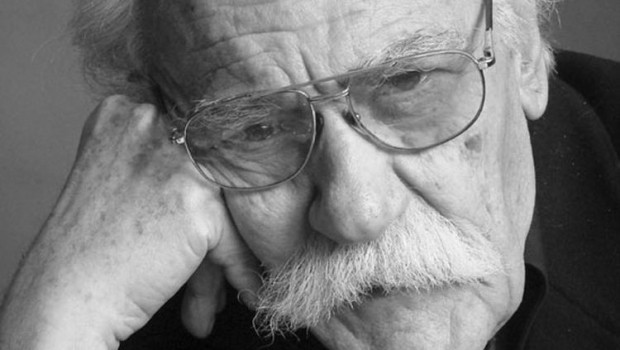

Roger Scruton

You being the realist against the idealism of Alain Badiou, don’t you think the world needs a bit of idealism?

No, I think it needs a bit less idealism. The 20th century was created by idealism. Communism and fascism and nazism were all based on idealized systems, on what the world should be ideally, and how it isn’t what it should be; and therefore we are entitled to change it radically and take control of it in order to do so, and the immediate result is genocides, as we have seen. I think idealism of Badiou’s kind is extremely dangerous. I was there in 1968 in Paris, at the time when he was in the streets shouting out his ideals and it was enough to convert me to the other side.

Really? It was that bad?

It was that bad. Seeing these arrogant young people pretending that they represented the workers, whereas in fact they were wealthy by-products of the middle class and wanting to dictate to everybody the system of politics which they had conceived from their half-educated reading. And it stayed in that class of French intellectuals ever since. I think people like me have a duty to be realistic in opposition and say, look, this unity between the intellectuals and the workers, who was actually creating it? It was you, intellectuals. How many workers were involved? Very few, only those that you could control through trade unions. Let’s get rid of all those illusions and treat people as they are.

Surely you must think that there are things in the world today that are wrong and that should be changed.

Yes, of course. There are lots of things that are wrong and should be changed, but the question is how. The revolutionary way of addressing this question is to form together a small conspiracy of the elite to craft a solution and then impose it from above on the mass of mankind. I take the other view, which is the classical English view, which is that people should be given the freedom to understand their problems and address them from their own existing repertoire of social and political gestures and gradually come to some consensus, and that is a very different approach.

You are not saying then that we need a new aristocracy?

No. In my book on green philosophy I do describe what I think of as an alternative to these top-down solutions: the big problems of the environment, and how my alternative is to make the space for ordinary motives of ordinary people to take charge of the problem. Well the problem, first of all, has to be local. This is one thing I agree with what Badiou said in his lecture, which is the great points of transition in communities and also in individuals are local. They involve some problem that you are living through and which also makes you recognize your dependence upon other people, how you need them to join with you in order to solve this problem. And the Dutch did this very well in the seventeenth century. They had a huge environmental problem, after all, and they built the dikes to solve it. You know, it was one of the great achievements that was not done by some committee of revolutionary vanguard imposing upon the ordinary Dutch people a solution they didn’t want. It was ordinary people locally getting together to build their own dike, and gradually the country solved its problem. I think that many of our environmental problems today can be confronted in that way, as long as you keep those intellectuals out of them.

Finally you mention that the sacred should return to our society. Can you explain that a little bit?

Yes. I think human beings are incomplete without a concept of the sacred. They must have a sense that this world in which they live has moments, places, events, people, etcetera, which are in some sense standing outside the ordinary course of events. They are not just things to be bargained with, things to be bought and sold but, as it were, stand in judgment on us. And all of us have that sense when we are children, because that is instinctive in us, but it is wiped away by the materialism, by the ease of satisfying our wants, and so on. And the result is that we are in a certain measure bereft, bereft of something that is needed for our happiness, which is the sense that we are in good relations with sacred things.

Traducido por David Medina Portillo

Usted es un realista en contra del idealismo. ¿No cree que el mundo necesita un poco de idealismo?

Pienso más bien lo contrario. El siglo XX fue creado por el idealismo. Comunismo, fascismo y nazismo descansan en sistemas utópicos: sobre lo que debería ser un mundo ideal. Y como esta realidad no es cual debe tenemos, en consecuencia, derecho a cambiarla radicalmente asumiendo el control. Según hemos visto, el resultado de todo esto puede ser el genocidio. El idealismo del tipo de Badiou es extremadamente peligroso. Yo me encontraba en París en 1968 cuando él ocupaba las calles vociferando sus ideales. Fue suficiente para mudarme al otro lado.

¿Realmente? ¿Tan malo fue?

Estuvo muy mal. Ver a esos jóvenes arrogantes pretendiendo representar a los trabajadores cuando en realidad eran ricos o subproductos de la clase media deseando imponer al mundo un sistema político concebido a partir de sus lecturas de preparatoria. Y esa clase de intelectual francés sobrevive así desde entonces. Pienso que gente como yo tiene el deber de ser realista en la oposición. Por ejemplo, preguntar sobre esa unidad entre los intelectuales y los trabajadores: ¿quiénes la crearon realmente? Fueron ustedes, los intelectuales. ¿Cuántos trabajadores estuvieron implicados? Muy pocos, sólo aquellos que ustedes podían controlar mediante los sindicatos. Debemos deshacernos de todas estas ilusiones y tratar a las personas como lo que son.

Seguramente debe pensar que hay cosas erróneas en el mundo y que deberían cambiar.

Sí, desde luego. Existen muchas cosas equivocadas que deberían cambiar, pero la pregunta es cómo. La manera revolucionaria de abordar esta cuestión es crear una pequeña conspiración de élite para trabajar en una solución y, luego, imponerla desde arriba a la masa de la humanidad. Yo asumo la otra opinión, la visión clásica inglesa según la cual la gente debe tener libertad para comprender sus problemas y enfrentarlos desde su propio repertorio político y social y, gradualmente, acceder a un consenso. Un enfoque muy diferente.

¿No pensará usted en la necesidad de una nueva aristocracia?

No, por supuesto. En mi libro sobre filosofía verde describo lo que considero una alternativa a estas soluciones de arriba a abajo: en los grandes problemas medio ambientales, por ejemplo, mi alternativa consiste en crear espacios para que los motivos ordinarios de la gente ordinaria se encarguen del problema. Dicho problema tiene que ser ante todo local. En esto estoy de acuerdo con lo que dijo Badiou en su conferencia: los puntos de transición determinantes, tanto en las comunidades como en los individuos, son locales. El problema por el que usted está pasando le hace reconocer su dependencia de otra gente, le permite saber cómo necesita de esa gente para solucionar determinado conflicto. Los holandeses lo hicieron muy bien en el siglo XVII. Tenían un gran problema ambiental y construyeron diques para resolverlo. Fue un gran logro realizado no por algún comité de vanguardia revolucionaria imponiendo sobre los holandeses comunes una solución que ellos no deseaban. Era gente ordinaria reunida en la zona para construir su propio dique. Gradualmente, el país superó sus dificultades. Pienso que muchos de nuestros conflictos ambientales de hoy pueden ser enfrentados del mismo modo –mientras, mantenga usted lejos de ahí a los intelectuales.

Finalmente menciona que lo sagrado debería volver a nuestra sociedad. ¿Puede abundar un poco más?

Creo que los seres humanos están incompletos sin un concepto de lo sagrado. Deben tener la sensación de que este mundo en el que viven tiene momentos, lugares, acontecimientos y personas que, en cierto sentido, están fuera del curso normal de los acontecimientos. No son cosas con las cuales negociar, que se compran y venden, sino, por decirlo así, de pie en el juicio sobre nosotros. Todos contamos con este sentido cuando somos niños porque es instintivo en nosotros aunque ha sido borrado por el materialismo, la facilidad de satisfacer nuestros deseos, etc. El resultado es que carecemos de algo necesario para nuestra felicidad, nos encontramos privados del sentido de estar en buenas relaciones con cosas sagradas. [Traducción de D.M.P.]