Fernando Botero: A dimension of portliness

Fernando Castro R.

It was probably in New York and in the early seventies when I first saw Fernando Botero’s paintings. I cannot remember exactly which ones, but I recall what may arguably be described as their “style”: impeccably executed portraits of people whose most conspicuous common denominator was their portliness. The settings and atmosphere of the paintings also struck me as unexpectedly familiar: maybe an aunt’s house, a small Andean town, or a bucolic South American landscape. They were of course figurative paintings, somewhat naïve, and one might also say “realistic” —with a grain of salt— because even the objects of his still lifes appeared overly voluminous.

At first, a viewer might think that the rotundity of Botero’s subjects is a kind of social critique. In other words, that Botero is showing us that villains become obese as a moral result of their abuses and their overindulgence in gluttony, greed, envy, and such. But alas, the pictorial plumpness of Botero’s characters is no critique! Rather, it is an attribute shared equally by friends and foes, heroes and villains, victims and victimizers, literati and glitterati. Perhaps their portliness is a blessing that mothers thought healthy and wholesome in the 1950s. The artist himself adamantly, albeit somewhat euphemistically, describes this conspicuous attribute of his figures as “volume.” In fact, he has clearly stated, “I do not paint fatties. I have not painted a fat woman in my life. What I have done is to express volume as a part of sensuality.” Carlos Fuentes helped him drive this point across in a text he originally wrote for the book Mujeres. “Botero’s figures are not ‘fat.’ They are ‘space,'” Fuentes wrote. “They are not gluttons for sweets and pastry. They are hungry for space.” Indeed, the appetite for volume shows most prominently in Botero’s sculptures, strewn on public spaces in cities around the world. If it is existential space Fuentes was referring to —space to assert themselves (or himself)— they got that.

Mario Vargas Llosa also respected Botero’s “volume” jargon in the prologue of the book Botero (Editions La Difference. Paris: 1984). According to Vargas Llosa, for Botero, obesity is a point of view and a method rather than a concrete reality. “His fat men evidence a love of the lady, of volume, of color. They are a visual feast rather than the glorification of desire, a song of the appetites, or a defense of instinct.” I ask myself: why avoid the white elephant in the room? Is the power of rhetoric greater than the evidence of the senses? Will we stop seeing Botero’s figures as obese and start seeing them as simply voluminous? Or will the bard’s words, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet,” ring true?

Picasso went through periods in which volume played a substantive role in his depictions of the human body, but the figures that he produced were seldom so double-chinned, so… Precious. The single most conspicuous and unabashed case of subject portliness is probably the 1540 depiction of Henry VIII by Hans Holbein the Younger. Nevertheless, one reads more than volume into that historical royal portrait; kingly obesity and its biographical context is an important part of that work. In sum, it would be very disappointing to think that Botero’s oeuvre is a mere exploration of volume, given that there is so much more to it; so much at stake in reflecting about portliness, its causes and social effects, including perceptions.

There is one additional point to be made. One cannot but ask whether in much of Botero’s oeuvre there is a penchant for satire, held at bay by a deep-seeded humanism. It is a kind of satire that aims to unveil the human condition à la Goya or à la Daumier. The viewer needs to make up his/her mind about Botero’s work as he/she views through his satirical lens depictions not only of Colombian culture (dancing, prostitution, the military, the clergy, et al.) as well as of the history of painting itself, from a hefty Mona Lisa to a chubby Menina, from a beefy Colonel Aureliano Buendía to a bloated Arnolfini Marriage.

Portrait of Mario Vargas Llosa (1988)

To be fair, in order to appreciate Botero’s paintings properly, one has to get past the perception of price, fame, and podginess and engage theme and corporeal expression, confluence of line and form, mood, context, and relevance. Philosopher Arthur Danto (1924-2013), one of the most lucid American art critics, did exactly that in an essay titled The Body in Pain (The Nation, 2006) about Botero’s paintings of the Abu Ghraib prisoners in Guantánamo. Botero produced this work in 2005, after he had done similar work about the violence in his native Colombia. He offered to donate all the works in the exhibition to a museum or museums that would commit to showing at least some of them permanently.

Danto wrote, “As it turns out, his images of torture, now on view at the Marlborough Gallery in midtown Manhattan and compiled in the book Botero Abu Ghraib, are masterpieces of what I have called disturbatory art —art whose point and purpose is to make vivid and objective our most frightening subjective thoughts. Botero’s astonishing works make us realize this: We knew that Abu Ghraib’s prisoners were suffering, but we did not feel that suffering as ours. (…) Botero’s images, by contrast, establish a visceral sense of identification with the victims, whose suffering we are compelled to internalize and make vicariously our own. (…) The mystery of painting, almost forgotten since the Counter-Reformation, lies in its power to generate a kind of illusion that has less to do with pictorial perception than it does with feeling. (…) Although the prisoners are painted in his signature style, his much-maligned mannerism intensifies our engagement with the pictures. This is partly because the prisoners’ heavy flesh—broken and bleeding from beatings— looks all the more vulnerable to the pain inflicted. While their faces are largely covered with hoods, blindfolds and women’s underpants, their mouths are twisted into expressions of pain or agony.”

Abu Ghraib prisoner (2005)

Danto’s comments about these works by Botero are particularly telling precisely because he is one of the thinkers who have given credence to many contemporary artists —from Andy Warhol to Damien Hirst— blamed by reactionary critics for everything that is wrong with art today. Mind you, Danto is not one of the opaque, obscurantist dilettanti who have turned criticism into a game where artworks matter little and adherence to absurd theories is paramount.

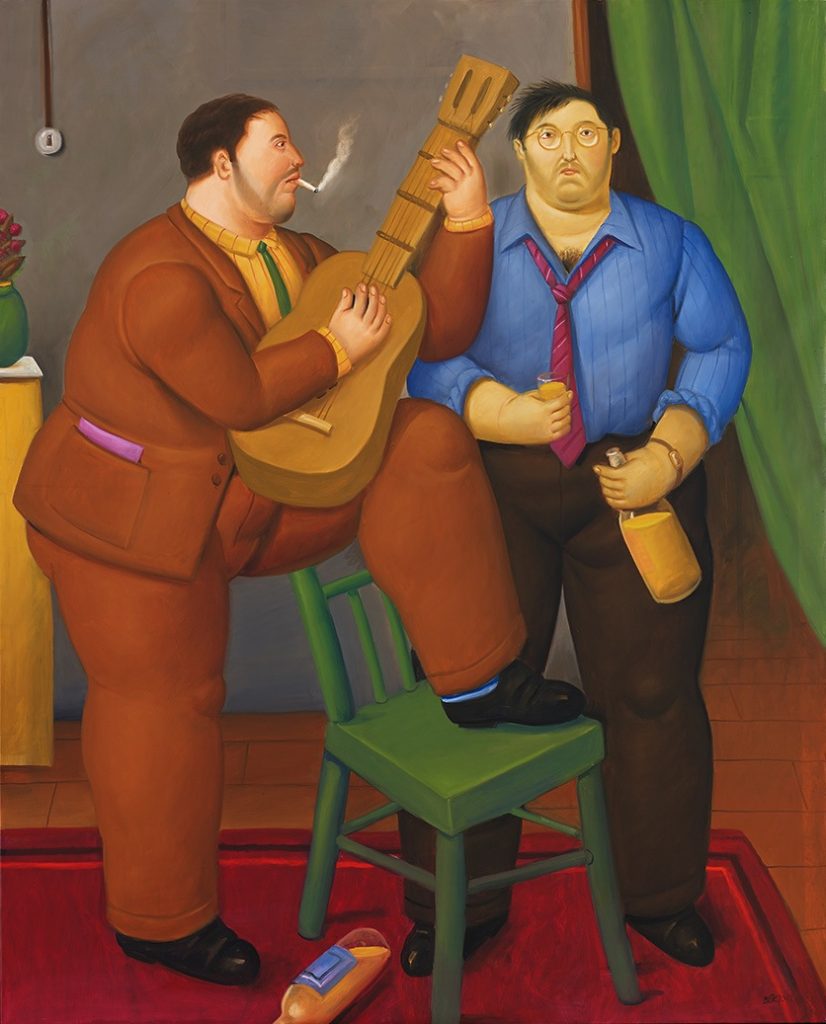

“Two Friends” 2012 Oil on canvas 66 x 53 inches – 167 x 135 cm Signed lower right, “Botero 12” Provenance. Acquired directly from the artist’s collection

Official Portrait of the Military Junta (1971)

For decades, Botero’s signature paintings and sculptures have spread across the world. He is a prolific artist, said to have produced over 3,000 paintings, over 300 sculptures, and a myriad of drawings and pastels. Every time I visit New York, I see more of his oversize sculptures populating the city. On Park Avenue alone you can run into Maternity (1989), Cat (1984), Roman Soldier (1985), Reclining Venus (1988), Woman with Serpent (1993), Torso (Man) (1992), Horse (1992), Woman (1989), Man (1990), Rape of Europa (1992), Woman with a Mirror (1987), Bird (1990), Seated Woman (1976), and Torso (Woman) (1982).

It is a moot question whether Botero’s work is a corollary of the inflated hyperbole of some of the Latin American “boom” literature. I do not recall obesity playing an important role in any of the boom’s narratives, but one might argue that the exaggerated zeal with which Vargas Llosa’s character Captain Pantoja undertook his mission to supply the army with prostitutes constitutes a case of gargantuan disproportion. Similarly, García Márquez’s short story The Most Beautiful Drowned Man in the World, about an enormous dead corpse that elicits both lust and pity among the women of a small Colombian coastal town and ends up posthumously improving the life of its denizens, is another case of humongous magnification.

Botero himself dismissed any literary connection to his works in an interview granted to the BBC in 2005. More to the point, he explicitly rejects the connection of his work with García Márquez’s oeuvre by stating, “I do not do magical realism. What I do is improbable, but not impossible.” However, in said interview he seems more interested in claiming priority than in the similitudes I have pointed out above. “If you look at my catalogs,” he stated, “you can see that this Rabelaisian world occurs in my work since 1955. García Márquez starts in 1966, when he publishes One Hundred Years of Solitude.” My take is that García Márquez himself could not have felt comfortable with the description of his work as “magical realism,” or even Alejo Carpentier’s alternative, “lo real maravilloso.” In my opinion, both terms are an attempt to account for some content in the narrative, more than what happens at the sources of the narratives or how these are processed in the authors’ writings as they incorporate popular oral traditions and beliefs.

When I was a graduate student in philosophy in the 1980s, William Canady, a Rice University professor of architecture, timidly asked me if I was familiar with the work of Fernando Botero, an artist whose painting Bird in a Cage (1969) held a prominent place in his beautiful home, and whom nobody in Houston seemed to know. Thirty-six years later, Houstonians are getting a chance to see an exhibition of this Latin American master at the brand new Art of the World Gallery on Westheimer. I sadly discovered that it is a show unlikely to have been picked up by any of our local museums, even though many museums around the world have hosted Fernando Botero’s major exhibitions: the National Museum of China, the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Delaware Art Museum, the Kunsthal Rotterdam, etc., etc.

Images Courtesy of Art of the World Gallery.

Cover Image:

“Standing Woman” 1998

Oil on canvas

81 x 49 inches – 206 x 124 cm

Signed lower right

The painting is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity

Provenance

Acquired directly from the artist’s studio

Fernando Castro es artista, crítico y curador. Estudió filosofía en la Universidad de Rice con una beca Fulbright. Es miembro de la comisión técnica del FotoFest y del consejo consultivo del Center for Photography de Houston. Editor y colaborador de las revistas Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magaziney Spot.

Fernando Castro es artista, crítico y curador. Estudió filosofía en la Universidad de Rice con una beca Fulbright. Es miembro de la comisión técnica del FotoFest y del consejo consultivo del Center for Photography de Houston. Editor y colaborador de las revistas Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magaziney Spot.

©Literal Publishing

Posted: December 4, 2016 at 6:48 pm