HOW DID YOU BEGIN TO SING

Martha Bátiz

Translated by Gustavo Escobedo

My mother played the flute, and for a while she played in a local orchestra where we lived. She loved music. She took me to the opera for the first time. She taught me to love music.

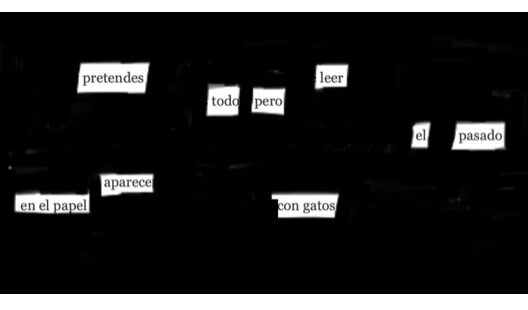

I re-read my entry with satisfaction. It sounded good despite not being entirely true.

When we returned from the burial Father called Tamara and Eduardo. The four of us met in his study. I don’t remember his exact words, except that he changed “they killed her” for “she died,” and from then on I did the same. Days passed and Mother’s things remained in their place. We did not return to school because Father had begun to organize our departure from Venezuela and he thought it inconvenient for us to go. He hired a private tutor so that we would not lose the school year, and he was content with that. None of us asked questions, probably because we knew that Father would say nothing more. Mother’s portrait still hung on the wall. It was the only thing that spoke of her. It was impossible to sleep. All three of us cried at night, but only Eduardo and Tamara managed to fall asleep out of exhaustion. Headaches forced me to get up, to flee from bed, to wish I could turn into dust so I could vanish from there. Father wandered the house all through the night, and I could hear his footsteps everywhere, dragging along with the desolation of someone who is lost and tired and doesn’t know where to go. He would enter our bedrooms stealthily and would stand a long while at the foot of the beds. It made me scared. I would only get up once he had left. I didn’t know what he was looking for. I began to follow him and to watch his movements without him noticing.

One night, after stopping in all three bedrooms, he sat down in the living room. While I watched him I made a wish. I asked with all my heart that everything return to how it was, so I could remember Mother’s voice. I swore that I wouldn’t care about the shouts and the blows. I wouldn’t even mind repeating that afternoon in which Mother begged, “Not in front of the children, please.” Nothing stopped me from wishing time would turn back. In truth, it was not necessary to witness those scenes to know how much those slaps hurt. Father had large hands.

Tamara and I had opted for hiding behind the door, embracing each other. Or to hide under the bed when we heard the warning:

“Stop playing that fucking flute, I’ve had it with your constant tooting.”

Which would almost always be followed by:

“. . . .I’m almost finished.”

And then:

“I told you to shut up. I’m going to break your hands with that thing to make you understand.”

And one day:

“I’ve never hit you, and you’ve hit me three times now. Please forgive me, Eusebio.”

And another day:

“No more, please, no more.”

Almost every day.

There was also the sound of objects hitting the floor or the walls. Smashing. And the smell of sweat, of the salt of tears. Torn clothes, stained with a deep red that sometimes did not wash out. Once, from a slap, some little decorative stones flew from my mother’s glasses. Tamara and I had always loved those glasses. Our mother looked beautiful in them. We scoured the carpet for hours to find the little coloured stones one by one, so that our mother could stick them back in place. But in any case the frames were hopelessly twisted, and she was never able to wear them again outside the house. She would only put them on for us, and she would let us play with them.

After that, Tamara began to confront Father.

“Leave her alone, Dad! Let go of her. Don’t be a bully.”

“Get out of the way, Tamara! This is not children’s business,” and he’d push her.

“Don’t you touch my daughter,” and Mother would throw herself at him to defend her.

In the end, Father would apologize to both of them, and then lock himself with Tamara in his study. Who knows what things he said to her? Mother and I, with Eduardo in her arms, would walk away when the quarrel ended. My sister always came out of there, almost immediately ready to eat towers of Sugus and to play as if nothing had happened. By contrast, I found it difficult to forgive him. I ended up doing so, but not willingly. He was diligent and sweet for the next few days, and Mother insisted that we not hold a grudge. I never really understood why Father was so aggressive. I also didn’t know why Mother put up with him for so long, why she didn’t do something to save herself. What I did understand clearly after her death was that anything was better than this new silence, even the blows and screams. Anything, in order to have her back.

That night I was watching Father in the living room, each phrase of Mother’s was still formed of mute words. Again I wished in my heart that everything be as before. But as though in immediate response – crushing any possibility that my wish might come true – Father rose to his feet, took out the bag of Sugus which we always kept in a drawer of a cupboard, walked decisively to the kitchen, and threw the candy with rage into the garbage. He didn’t really comment on it the next day, nor afterwards. Only that we had to take better care of our teeth. None of us siblings dared make a protest, nor proposed to play again, even when we were alone. I have never eaten a single Sugus since.

The next day, so I wouldn’t also forget the sound of her flute, I began to use my voice to imitate the scales which she used to practice. The melodies she played. At least that was going to remain with me. No one was going to be able to take it away. It was the best way to suffocate so much silence and to breathe again. My green and cold Leonora stretched her neck fully to listen. This is how I began to sing.

- This excerpt belong to the title Damiana’s Reprieve, a Novella for Two Voices. Released by Exile Editions on Nov. 14th, 2018

Martha Bátiz is the author of A todos los voy a matar (Ed. Castillo, 2000); Boca de lobo, (Exile Editions, 2009) among many others. Her Twitter is @mbatiz

©Literal Publishing.

Posted: February 20, 2019 at 10:19 pm