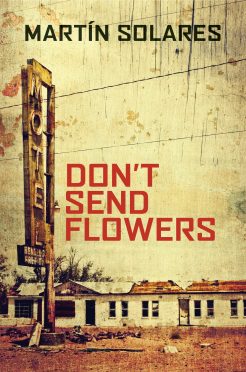

Don’t Send Flowers

Greg Walklin

Toward the end of Don’t Send Flowers, the police chief of La Eternidad describes his mission succinctly: “I’m going to enforce the law,” he says. “Even if that law is the Ley de Fugas.” While Ley de Fugas literally means “law of flight”—the extrajudicial ability of police to shoot, or even kill, fleeing suspects—”Fuga” also means “fugue,” which, in both the multivoice musical form and as a sort of epileptic or hysteric state, could not more aptly encompass Martín Solares’s new crime novel.

The first half of the book plays out like a typical detective yarn: Carlos Treviño, an ex-cop, is recruited by Rafael de Leon, a rich magnate, whose beautiful 16-year-old daughter Cristina has been kidnapped. Mysteriously, there has been no ransom call. Her boyfriend, the only witness to the kidnapping, is unconscious and in the hospital, and the detectives have proved to be of no help. With only dead ends, De Leon turns to Treviño, whose insistence on actually solving crimes led him to be dismissed from the corrupt police department.

Besieged by corruption and violence, kidnappings are common in La Eternidad. With de Leon’s money and shady business ties, Treviño’s potential list of suspects is long. Fearless and clever, Treviño suspects everyone, searching the city and roaming its pier, even going so far as to infiltrate a rural cartel operation. His reluctance to get involved in the case proves to be prescient. Soon enough, both the police and the criminals are after him.

The second half of the novel follows Chief Margarito Gonzalez, an enemy of Treviño’s who is inextricably linked with everything going on in the town. Margarito has had a long career. While his survival instincts are incredible, he is also mendacious, deceptive and cruel. (Fortunately, nobody compares him to a cockroach, which, while apt, would have been a cliché.) Facing forced retirement, he has negotiated that his idealistic son, who hates his father and had previously moved to Canada, will succeed him. Though he is many bad things, Margarito also understands that he is irredeemable: “He wanted to defend himself,” Margarito reflects in the third person at one point, “but he had no ammunition. To be defensible, he needed to have lived a different life.”

Solares’s prose, translated by Heather Cleary, is taut and unobtrusive. Sometimes it shimmers (at one point clouds of burnt sugarcane “seemed intent on erasing all trace of the highway”) and other times details—such as the types of gun everyone is using—get in the way of the narrative drive. The dialogue, for the most part, punches and weaves. Margarito’s hypnotic half of the book is the most enthralling; Solares seems to have thoroughly inhabited a man for whom finding the “right” thing is akin to finding true north in space. All of the characters, even the ones who fall into detective story tropes, still feel real and seem to ache off the page.

While Treviño essentially solves the mystery halfway through the book, Don’t Send Flowers continues to unravel the remainder of what has stuck La Eternidad in an endless cycle of violence; who kidnapped Cristina, and why, is only a part of what the book is all about.

Indeed, the novel is about La Eternidad itself as much as anything else. The city used to be a beautiful and safe seaside spot, until everything changed:

Drivers used to stop for pedestrians. You’d get a friendly, sincere greeting from everyone you passed on the street. You could leave your house or your car unlocked, your heart open; you could take your girlfriend for a walk under the stars, let your kids play soccer in the street. But that was then. None of that’s possible now, when everyone does whatever they want and your survival instinct screams: Keep your mouth shut and your eyes down, and get out while you still can. It’s every man for himself.

Now La Eternidad is a place overwhelmed by drugs and violence where killers burst into emergency rooms to finish off their targets, murdering surgeons and nurses, as well; where a de facto curfew is in place and the police are cowed into submission by syndicates. Thanatos should be its mayor.

The border between the United States and Mexico has been the foundation of a rich variety of literature. (If you enjoyed Don Winslow’s morbid Cartel trilogy, Solares’s book is a perfect codicil.) Don’t Send Flowers isn’t so much about the border as a theme or focus, but rather an exploration, through the crime novel, of what such a liminal life in northern Mexico has become. While much here has been explored in other books, the genre that Solares subverts does prove to be a novel entré into this miasma, especially showing it from south of the Rio Grande: it is one giant crime spree that shows no sign of ending.

What all of these books share is a difficulty in understanding the true scope, roots and causes of the crimes, or how they have affected the people who have died or lived through them—people who, as Solares writes, “went from being the gentlest and kindest in the country to being the most nervous and cagey, the ones most afraid of conversation.” While such enormity is plain, that has not made it any easier to comprehend.

“The great tragedy in this country,” Trevino explains at one point, “is that the clues are all right there, in plain sight, but no one wants to see them.”

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

©Literal Publishing

Posted: March 28, 2019 at 9:56 pm

![Entre Pink Floyd y el INAPAM [1]](https://literalmagazine.com/assets/patti-620x350.png)