21st Century Schizoids

Esquizoides del siglo XXI

Adriana Díaz Enciso

The other day I fell prey to a dreadful thought: the more the 21st century moves forward, the less people there will be who’ve known the world without internet and the badly named smartphones. There will be no hope then of returning to at least a minimal existential balance, because if us 20th century survivors try to explain to people who were born with the algorithms encrusted in their grey matter how it was to live with mental space and silence, they won’t be able to understand, having never known them. I imagined a world in which every person of my generation and previous ones grows old trapped in this vile machinery and the fractured perception of reality that is its mark. I can’t imagine a more abject loneliness.

Unfortunately, this panorama isn’t the fruit of a rampant imagination. If invoking it left me in a rather dismal mood, it’s because that loneliness, and the incalculable loss it denotes, are in fact already part of my everyday life and the life of many of those who knew an abysmally different reality. There are in my life young people, teenagers and children whom I love dearly who haven’t experienced the world without the intermediation of digital technology and cyberspace’s phantasmagoria.

It is true that all generations must face sooner or later the dissociation between the reality in which we grew up and were young, and that of those who come behind us. It’s an inevitable and painful crisis, but it’s also a chance to mature and be open, with curiosity, to the promise of a new time and of the continuity of human experience. I doubt, however, that there’s ever been a generation gap more unbridgeable than the one that separates 20th century people from those who’ve been born in the 21st, because now it is not only a matter of changing moral codes, philosophical and political positions, ideologies, fashions or aesthetic tendencies, but a profound cognitive alteration. Human life as an appendix of the computer (and the pocket computer that mobile phones are) entails a convulsion in the way we inhabit and conceive the universe much more violent than that of the Industrial Revolution, even if it is a later consequence of the former’s insane cult of progress. Digital technology has already altered, in a seemingly irreversible manner, not only the contents of our mind, but our mental functions themselves.

There is of course a wealth of research and papers on what this means, and what are its psychological, philosophical, economic and political consequences (I recommend to follow in this regard author Naief Yehya’s keen reflections), but with the passage of decades, such research will be carried out by individuals whose cognitive processes won’t have ever been others than those of the fragmentation imposed by this technology, in an intellectual and even neurological loop from which there will be no escape.

For many of those who were born in the 20th century, the perception of reality in the 1920s seems much closer and intelligible than that of the 2020s, and I’d even go back to the 1820s and beyond. The cognitive crack happens there where living with the machines, with the manufactured objects which are an inherent condition of being human since the first arrow was created, becomes an existence lived almost completely from the machine.

***

I’ve mentioned loneliness. Few forms of loneliness can be greater than that of inhabiting an unrecognisable world; of feeling a stranger not in a country, but in the time you live in. You can’t flee time. It’s like living in an incomprehensible, hostile and sterile planet in which the foundations of what I conceive to be a human life are being constantly eroded, and in which sharing my uneasiness is hard because the language spoken has no room or words for what, in my experience, is the meaning of being human.

I don’t have a smartphone. I’ve resisted. I have a simple no-internet Nokia with which you can make or receive calls, send or receive text messages, and that’s it. You can have no doubt that society makes me pay for this tiny act of rebellion, for all the time there are more and more practical matters (various paperwork, though there’s no paper involved; medical appointments and an endless etc.) that become complicated because society assumes that we all have a smartphone, and that we all passively accept it as the intermediary between us and any manifestation of reality. As if it wasn’t enough that neither me nor anybody else have been able to defend ourselves from the imposition to sort out our life online, through the computer if by any chance the last bastion of resistance to the smartphone hasn’t succumbed yet. Like all of you, I spend a lot of time each day trying to work out issues related to the scaffolding of everyday life through mechanisms that I don’t understand, which fill my head with a proliferation of undesired images that induce mental lethargy and, often, depression. It makes me shiver to think of the elderly, for whom technology is much more alien than for me, trying to navigate this landscape of sheer artifice where personal contact is reduced as the language of the robotic-esoteric expands in a proliferation of self-referring loops.

It’s true that my skills for technology are rather precarious, in part because I loathe it, in part, I guess, because the area in my brain that holds such faculties isn’t very developed, but let’s not delude ourselves: in a couple of decades we have reached the fearful point where no one, not even the so-called IT experts, fully understands this technology. I’m sure I’m not the only one who has sought, through chats, the help of ‘expert’ technicians in moments of digital despair, just to find that the technician doesn’t understand the problem either nor can sort it out, a conclusion reached after hours, during which both the technician and the desperate person have descended into a hell of screen prestidigitation with elements that hold no discernible meaning.

Despite belonging to this civilisation, to this global dependence on the device that spreads at ever greater speed to the farthest reaches of the earth (and the space around, littered with satellites and scrap), I can’t help being astonished by the fact that such a civilisation is incapable to see the warning signs; that it can’t detect the state of emergency in our dependence on and impotence before the machine, and that we go on expanding the areas of our life and our society that depend on it entirely. I still find the docility with which we surrendered to the machine and the virtual reality it generates, without thinking of what’s going to happen to all of us the day the machine breaks down, perplexing.

Of course, I do know that internet, computers and even social media have many virtues, which we know well. However, at some point at the turn of the century, we humans decided that internet, computers, mobile phones and their spurious reality were more important than ourselves, and that we’d gladly offer up to them our whole life. Why?

I’m aware of the paradox: I am writing these lines in a computer, and you, readers, will read them online. This situation has many advantages, such as the possibility to write for a publication that I enjoy, that nurtures me intellectually and that I respect, even if I don’t live in the country where it’s created, or the fact that my contributions to Literal Magazine can be read in any country.

How was the experience of writing for a journal when I started my career? Believe it or not, I delivered my contributions to newspapers and magazines in person. I wrote them in a typewriter, using carbon copy paper. This rudimentary method offered enormous advantages too. The main one: to go to the publications’ headquarters, meet the editors in person and have a chat with them, even if briefly, and then go to the nearby café (there is always one), where usually I would find other authors, journalists, editors, to extend the conversation. That is to say, the world became broader, richer.

You’ll say we wasted much time. I ask, really? How much time have you lost in your life trying to sort out unfathomable computer or mobile phone problems, trying to register in a webpage because your work, the Inland Revenue or whatever demands it, trying to renew your passport, buy a plane ticket or carry out any of the innumerable actions that cannot be done any other way anymore? How much wasted time waiting for the response from the chat guys who’re supposedly going to help you, just to realise that the response is not that of a human being, but of a robot who doesn’t understand anything at all? How many lost instants, which accumulated become hours and days of the only life you have, in telling the pop-up window that assaults you when you open a webpage that you don’t want its cookies, that you don’t want to subscribe to anything, that you don’t want their messages, because if you don’t respond to all that, you can’t have access to what you were looking for? Your life spilling out between your fingers—digitally, we may say—and without the benefit of an interaction with a human being. And have you noticed the mental state in which this sad adventure leaves you?

I’m sure I’m not the only one who, in a fit of computer rage, has insulted a robot. It is sadly funny—to yell at the telephone, or yell with your fingers in the chat: “I want to talk with a human being, not with a fucking robot!”, then hear the said robot say sweetly, “So you want to talk with one of our representatives, is that right?” Robots have no dignity. They don’t, because they’re machines and products of the machine. We should stop calling them robots, which confers to them a kind of personality, a kind of life, and take them for the machines they are.

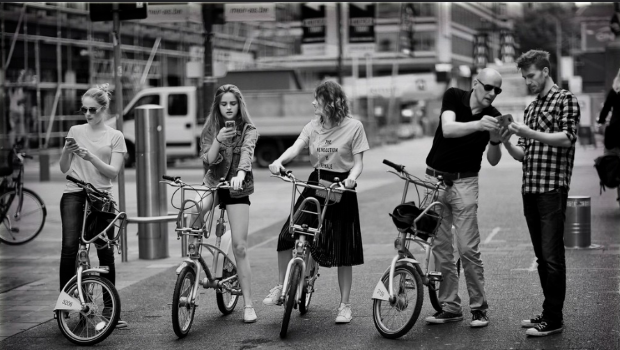

But let us go back to loneliness: the loneliness of living among addicts. To find myself in the street surrounded by them, stuck to the screens of their multiple gadgets, their mobiles already an extension of their body, everywhere, at any time. The fear, also, of what, eventually, the members of a society of addicts may be capable of, after decades of subjection to the mental deterioration caused by their addiction.

The issue of addiction has also been the theme of endless research, but personal experience is enough to understand it. Even without a smartphone, I can detect the symptoms in myself, for instance when I’m looking for something online and end up browsing through other sites, reading some news, watching some video, without any need to do so and, it would seem, with no will of my own. Like eating in one go a whole box of chocolates, or drinking a whole bottle of whiskey or whatever, simply because, in that moment, life stopped revealing itself as life; because, without even being aware of it, we allowed compulsion to drag us down. However much I try to resist, I have succumbed too to a great extent, and however much I try to be on my guard and defend myself, society forces me every day more to live immersed in this indescribable misery. My mind, the activity of my brain, aren’t the same they were in pre-Internet times, and therefore, the substance of my life is also altered. The machine has managed to intrude and interfere in my reality, transforming it in a hideous manner, and there seems to be no turning back, at least during my lifetime.

If this is depressing and frankly horrendous, how to express what it means that, for newer generations, there isn’t even the notion of a loss, because this is the only way of life that they’ve been made to believe is possible? How did we allow this to happen to us? How is it possible that, from the 20th century, when “this”—this monster—was bred, we thought we had the right to inflict it on our 21st century’s fellow men and women? To inflict it on our youth, on the future. For the responsibility is ours.

With infinite sadness, I want to tell those young persons that it isn’t normal to spend all your waking hours depending on an artifact that you simply can’t let go of, the incredible speed of which is not something created with your benefit in mind, but the product of competition among big companies to beat each other in the dominion of the absurd, as well as of the “progress” of military engineering; that it’s not normal that this one gadget rules your entire life, while you’re living under threat of being stripped, through the very same gadget, of your data, your money, your identity, your work and even your face, which anyone can steal to simulate that you’re doing something you’ve never done, through the deepfake technique; nor is it normal that thanks to these very methods, you can never know whether what you watch obsessively is actually real or not; that it isn’t normal that, in order to protect yourself, you must prop up your life with a heap of passwords impossible to remember and security codes, the owners and controllers of which are the gadget and the invisible web, cloud and technology that controls them; that it isn’t normal that you put that gadget and that technology in the hands and mind of your children at their earliest age, nor the fact that through them your children are under the constant threat of predators; that it isn’t normal to rule your love life through the above-mentioned gadget, nor projecting the whole of your emotional life on that simulacrum of communication called social media; that it isn’t normal to take pictures of everything, compulsively, to then “upload” them on a multiplicity of “platforms”, even when neither the pictures nor the platforms have any meaning whatsoever, thus multiplying the avalanche of dissociated images that subjugates us, and even less normal to take those pictures instead of seeing what you’re photographing—instead of living; that it isn’t normal to walk (stumbling) down the street or go around in public transport like a zombie, oblivious to your surroundings, without seeing the light or darkness or the time of year, or the people around you, because you’re engrossed in the squalor of that endless, inane procession of images, videos and vacuous information; that it isn’t normal to ask your gadget everything you don’t know or have forgotten, even if you’re not particularly interested to know, due to a neurotic anxiety that renders you incapable of bearing silence, the natural rhythm of time, uncertainty or solitude, and furthermore, without realising that this anxiety makes you sink deeper into loneliness and alienation; that it isn’t normal that in every public space we’re at the mercy of the vile noise coming from the gadgets of others who’re in a phone call, listening to music, watching football matches, ads or any other “content” with their speakers on because they have no notion of the respect due to the space and silence of others; that it isn’t normal to entrust your whole life to that gadget and believe that it will protect that life, nor to make of it your map, losing forever the opportunity to get lost and discover something new; that it isn’t normal that through that contraption and that technology anyone can know where you are; that it isn’t normal to be “connected” 24 hours a day with other gadgets or “the cloud”; that it isn’t normal to hand over all information about our identity and our own affairs to that technology, and accept the surveillance of governments, marketing schemes and any other rogue without even thinking of defending ourselves but, on the contrary, gladly surrendering such information; that it isn’t normal to believe that the gadget you can’t let go of is your mirror (it isn’t), or to believe that the “enhanced” pictures that you take thanks to its sophisticated technology are reality; that it isn’t normal that, while you’re working, you’re being besieged by pop-up windows telling you that your computer is at risk and you have to restart it or install some software you don’t understand and do not know whether it’s good or bad because you don’t know if you can trust the pop-up window; that it isn’t normal either to read some source of information while more pop-up windows make you turn elsewhere, announcing products or talking about something else; that it isn’t normal to read, get informed, follow, for instance, the news about a brutal war while the aforesaid bombardment of images and words try to divert your attention elsewhere, turning what you read into spectacle; that it isn’t normal to live, work and get information under the yoke of a relentless method of distraction; that it isn’t normal to feel that if you lose your smartphone you’re losing your life and are at risk, that you have lost yourself, without noticing that the losses and risk are in fact due to your smartphone.

Those of us hailing from the already remote 20th century remember very well a time when none of this fragmentation, this nightmare, was necessary. We did have our many and dire problems. The famous King Crimson song, the title of which I’ve borrowed for these musings, is really talking about those problems, and not about what it would be our lot to see in the 21st century, because Peter Sinfield, the author of the lyrics, couldn’t have possibly imagined, in 1969, the hell we would enter voluntarily, without complaint. We have witnessed how from the useful, the novel, the genius elements even in the new technology, we slid down into this state of collective alienation and numbness, first without noticing, then without being able to defend ourselves. It is no wonder that so many people now seek in meditation and mindfulness a hold so that they don’t go insane, but there is no meditation that can save us if we don’t first turn off the phone.

It is curious how we engage in protests and campaigns against violence, the climate catastrophe, racism, corrupt governments, all sorts of discrimination, injustice and inequality, yet nobody protests against this atrocious slavery. We walk meekly towards the slaughterhouse, smartphone in hand.

The dimension of the loss of our humanity in this fragmented world is inexpressible, and it is not—it never was—inevitable. We’ve permitted it out of weakness, ignorance, frivolity and indolence. It’s about time to wake up—it’s getting late.

-Imagen by Fouquier

Adriana Díaz-Enciso es poeta, narradora y traductora. Ha publicado las novelas La sed, Puente del cielo, Odio y Ciudad doliente de Dios, inspirada en los Poemas proféticos de William Blake; los libros de relatos Cuentos de fantasmas y otras mentiras y Con tu corazón y otros cuentos, y seis libros de poesía. Su más reciente publicación, Flint (una elegía y diario de sueños, escrita en inglés) puede encontrarse aquí.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

El otro día fui presa de un pensamiento atroz: entre más avance el siglo XXI, quedarán menos y menos personas que hayan conocido el mundo sin internet y sin los mal llamados teléfonos inteligentes. No habrá entonces esperanza de retorno a un siquiera mínimo equilibrio existencial, porque si los sobrevivientes del siglo XX intentamos explicarles a personas nacidas con los algoritmos incrustados en la materia gris cómo era vivir con espacio y silencio mentales, no podrán entenderlo, no habiéndolos conocido jamás. Imaginé un mundo en el que todas las personas de mi generación y otras mayores envejecemos presas de esta maquinaria infame y la fracturada percepción de la realidad que es su signo. No puedo imaginar soledad más abyecta.

Por desgracia, este escenario no es fruto de una imaginación desbocada. Si haberlo invocado me dejó en un estado de ánimo más que sombrío, es porque esa soledad, y la pérdida inconmensurable que denota, son ya de hecho parte cotidiana de mi vida y de la de muchos de los que conocimos una realidad abismalmente distinta. Hay en mi vida jóvenes, adolescentes y niños a los que quiero entrañablemente que no han experimentado el mundo sin la intermediación de la tecnología digital y la fantasmagoría del ciberespacio.

Es cierto que a todas las generaciones nos toca enfrentar, tarde o temprano, la disociación entre la realidad en que crecimos y fuimos jóvenes, y la de los que vienen detrás. Es una crisis inevitable y dolorosa, pero una oportunidad también de madurar y abrirnos con curiosidad a la promesa de un tiempo nuevo, de la continuidad de la experiencia humana. Sin embargo, dudo que haya existido alguna brecha generacional más insalvable que la que separa a la gente del siglo XX de la que ha nacido en el XXI, porque ahora no se trata nada más de cambiantes códigos morales, posturas filosóficas y políticas, ideologías, modas o tendencias estéticas, sino de una profunda alteración cognitiva. La vida humana como apéndice de la computadora (y la computadora de bolsillo que es el celular) supone una convulsión en la forma de habitar y concebir el universo mucho más violenta que la de la Revolución Industrial, aunque sea su postrera consecuencia en lo que toca al culto demencial del progreso. La tecnología digital ha alterado ya, de manera que parece irreversible, no nada más el contenido de nuestra mente, sino nuestras funciones mentales en sí.

Abundan por supuesto los estudios de lo que esto significa y cuáles son sus consecuencias psicológicas, filosóficas, económicas, políticas (a este respecto recomiendo seguir las agudas reflexiones del autor Naief Yehya), pero con el paso de las décadas, estos estudios serán realizados por individuos cuyos procesos cognitivos tampoco habrán sido nunca otros que los de la fragmentación que impone dicha tecnología, en un circuito cerrado intelectual e incluso neurológico sin escapatoria.

Para muchos de los que nacimos en el siglo XX, la percepción de la realidad en la década de 1920 es mucho más cercana y comprensible que la de los años veinte que habitamos ahora, y me atrevería a remontarme incluso a los años veinte del siglo XIX y aún más lejos. El quiebre cognitivo se da ahí donde vivir con las máquinas, con los objetos manufacturados que son condición inherente de ser humanos desde que se creó la primera flecha, se convierte en una existencia vivida casi en su totalidad desde la máquina.

***

He hablado de soledad. Pocas formas de soledad han de ser mayores que la de habitar un mundo irreconocible; sentirse forastera no en un país, sino en el tiempo en que se vive. Del tiempo no se puede huir. Es como vivir en un planeta incomprensible, hostil y estéril en el que los fundamentos de lo que concibo como una vida humana son minados constantemente, y en el que es difícil compartir mi desasosiego porque el lenguaje que se habla es uno que no tiene cabida ni palabras para lo que en mi experiencia es el significado de lo humano.

Yo no tengo un teléfono inteligente. Me he resistido. Tengo un sencillo Nokia sin internet que sirve para hacer y recibir llamadas, enviar y recibir mensajes de texto, y nada más. Que no les quede duda: la sociedad me cobra este ínfimo acto de rebelión, pues cada vez son más las cuestiones prácticas (trámites varios, citas médicas y un interminable etcétera) que se me complican porque la sociedad asume que todos tenemos un teléfono inteligente, y que todos aceptamos pasivamente que éste sea el intermediario entre nosotros y cualquier manifestación de la realidad. Como si no bastara el que ni yo ni nadie hayamos podido defendernos de la imposición de resolver nuestros asuntos en línea, a través de la computadora si es que aún no cae el último bastión de la resistencia al smartphone. Como todos ustedes, paso mucho tiempo cada día tratando de resolver asuntos relacionados con los andamios de lo cotidiano a través de mecanismos que no entiendo, que llenan mi cabeza de una proliferación de imágenes no deseadas que me producen letargo mental y, a menudo, depresión. Me da escalofríos pensar en los ancianos, mucho más ajenos a la tecnología que yo, que tratan de navegar este paisaje de artificio puro donde el contacto personal se va reduciendo a medida que se expande el lenguaje de lo robótico-esotérico en una proliferación de bucles autorreferentes.

Cierto, mi capacidad de manejo de la tecnología es muy precaria, en parte porque la detesto, en parte porque, supongo, el área de mi cerebro que se encarga de estas facultades no está muy desarrollada, pero no nos engañemos: en unas cuántas décadas hemos llegado al pavoroso momento en que nadie, ni siquiera los llamados expertos en la tecnología de la información, la entiende del todo. De seguro que no soy la única persona que ha buscado ayuda de técnicos “expertos” a través de chats, en momentos de desesperación digital, para encontrarse con que el técnico tampoco entiende el problema ni lo logra solucionar, conclusión a la que llega tras horas en que tanto el técnico como la persona desesperada han descendido a un infierno de prestidigitación en pantalla con elementos que no tienen ningún significado discernible.

Pese a formar parte de esta civilización, de esta dependencia global del artefacto que se extiende con cada vez mayor celeridad hasta el último rincón de la tierra (y el espacio alrededor, sembrado de satélites y chatarra), no dejo de asombrarme de que dicha civilización no escuche las llamadas de alerta, que no registre el estado de emergencia de nuestra dependencia e impotencia de y ante la máquina, y que sigamos acrecentando las áreas de nuestra vida y nuestra sociedad que dependen totalmente de ella. Sigo encontrando inexplicable la docilidad con que nos entregamos a la máquina y a la realidad virtual que ésta genera, sin pensar en qué va a pasarnos a todos el día en que la máquina falle.

Sé, por supuesto, que internet, las computadoras y hasta las redes sociales tienen sus muchas virtudes, que conocemos bien. Pero en algún momento, en la transición entre el siglo XX y el XXI, los humanos decidimos que internet, las computadoras, los teléfonos celulares y su espuria realidad eran más importantes que nosotros, y que les ofrendaríamos gustosos nuestra vida entera. ¿Por qué?

Soy consciente de la paradoja: escribo estas palabras en una computadora, y ustedes, lectores y lectoras, las leerán en línea. Hay muchas ventajas en esta situación, como la posibilidad de escribir para una publicación que disfruto, que me alimenta intelectualmente y que respeto, aunque viva en un país distinto al de su sede, o el que mis colaboraciones para Literal puedan ser leídas en cualquier país.

¿Pero cómo era la experiencia de escribir para una publicación al principio de mi carrera? Lo crean o no, yo llevaba mis colaboraciones a revistas y periódicos en persona. Las escribía a máquina, con papel carbón. Este método rudimentario ofrecía grandísimas ventajas. La principal: ir a las oficinas de las publicaciones, conocer en persona a los editores, poder charlar con ellos aunque fuera brevemente, y luego ir al café cercano (siempre hay uno), en el que frecuentemente estarían otros autores y autoras, periodistas, editores, con quienes se alargaba la conversación. Es decir: el mundo se ensanchaba, se enriquecía.

Que se perdía mucho tiempo, me dirán. Yo les pregunto: ¿de verdad? ¿Cuánto tiempo de tu vida, lector, lectora, has perdido tratando de resolver problemas insondables de tu computadora o teléfono, intentando registrarte en una página web porque así te lo exige tu trabajo, o Hacienda o qué se yo, o intentando tramitar tu pasaporte o comprar un boleto de avión o llevar a cabo cualquiera de las innumerables acciones que ya no se pueden realizar de otra forma? ¿Cuánto tiempo perdido esperando que te contesten los del chat que se supone que van a ayudarte, sólo para darte cuenta de que no te responde un humano, sino un robot que no entiende nada de nada? ¿Cuántos instantes perdidos, que acumulados se convierten en horas y días de la única vida que tienes, en decirle a la ventana que te salta al abrir una página que no quieres sus cookies, que no quieres suscribirte, que no quieres que te manden mensajes, porque si no respondes a todo eso, no puedes tener acceso a lo que buscabas? ¿Cuántas veces te has sentado ante la computadora a hacer algo concreto, y se te han ido las horas, a veces la mañana entera, porque algún problema de origen técnico te llevó a otro lugar y a otro problema, y así hasta el infinito? Tu vida derramándose entre los dedos; digitalmente, digamos, y sin el beneficio de una charla con un ser humano. ¿Y te has fijado en el estado mental en que te deja esta triste aventura?

No he de ser la única que, en un ataque de cólera cibernética, ha insultado a robots. No deja de tener su triste gracia gritar en el teléfono, o gritar con los dedos en el chat: “¡Quiero hablar con un ser humano, no con un pinche robot!”, y escuchar al susodicho robot decir con dulzura: “Enseguida le comunicaremos con uno de nuestros agentes.” Los robots no tienen dignidad. No la tienen porque son máquinas y productos de la máquina. Deberíamos dejar de llamarles robots, apelativo que les da una especie de personalidad, de vida, y entenderlos como las máquinas que son.

Volvamos al tema de la soledad. La soledad de vivir entre adictos. Salir a la calle y verme rodeada de ellos, pegados a las pantallas de sus múltiples adminículos, los teléfonos celulares ya una extensión de su cuerpo, en todo lugar y a cualquier hora. El temor, también, de aquello de lo que pueden ser capaces, a la larga, los miembros de una sociedad de adictos tras décadas de sometimiento al deterioro mental que conlleva su adicción.

Lo de la adicción es ya tema también de innumerables estudios, pero la experiencia personal basta para entenderlo. Aún sin tener teléfono inteligente, reconozco los síntomas en mí misma en momentos en que estoy buscando algo en internet y termino echándole una ojeada a otros sitios, a alguna noticia, algún video, sin necesidad y, pareciera, sin voluntad. Como comerse de golpe una caja entera de chocolates, o beberse una botella entera de whisky o qué se yo, simple y sencillamente porque, en ese momento, la vida dejó de revelarse como vida; porque sin darnos cuenta siquiera nos dejamos arrastrar por la compulsión. Por más que intento ofrecer resistencia, yo también he sucumbido en buena medida, y por más que trato de estar alerta y defenderme, la sociedad me obliga cada vez más a vivir inmersa en esta miseria indescriptible. Mi mente, mi actividad cerebral, no son las mismas que en los tiempos pre-internet, y, por lo tanto, tampoco la sustancia de mi vida. La máquina ha logrado entrometerse e interferir en mi realidad, transformándola de una manera aborrecible, y no parece, al menos no durante lo que me quede de vida, que haya vuelta atrás.

Si esto es deprimente y francamente horrendo, ¿cómo expresar lo que significa que, para las nuevas generaciones, no haya siquiera el referente de una pérdida, porque este es el único modo de vida que se les ha hecho creer que es posible? ¿Cómo permitimos que nos pasara esto? ¿Cómo es posible que desde el siglo XX, donde “esto”, este monstruo, se gestó, nos hayamos creído con el derecho de infligírselo a nuestros semejantes del siglo XXI? A nuestros jóvenes, al futuro. Porque la responsabilidad es nuestra.

Con una tristeza infinita, quiero decirles a esos jóvenes que no es normal pasar todas las horas de vigilia pendiente de un aparato que te resulta imposible soltar, cuya increíble rapidez de acción no es algo pensado con tu provecho en mente, sino producto de la competencia de grandes compañías por sobrepasarse una a la otra en el dominio del absurdo, al igual que de los “avances” en ingeniería militar; que no es normal que ese solo adminículo gobierne tu vida entera, mientras vives bajo la perpetua amenaza de ser, a través del mismo, despojado de tu información, de tu dinero, de tu identidad, de tu trabajo, hasta de tu rostro, que cualquiera puede robarse para simular que estás haciendo algo que nunca has hecho, mediante la técnica de deepfake o “ultrafalso”, ni que debido a estas mismas técnicas, no puedas saber nunca si lo que ves obsesivamente es real o no; que no es normal que para protegerte tengas que apuntalar tu vida con un montón de contraseñas imposibles de recordar y códigos de seguridad, de los cuales el aparato y la invisible red, nube, tecnología que lo controla son también administradores y dueños; que no es normal que pongas dicho aparato y dicha tecnología en las manos y la mente de tus hijos desde la edad más temprana, ni que a través de los mismos estén ellos bajo la amenaza constante de depredadores; que no es normal regir tu vida amorosa a través del susodicho artilugio, ni proyectar tu vida emocional entera en ese simulacro de comunicación que son las redes sociales; que no es normal estar tomando fotos de todo compulsivamente, para luego “subirlas” a una multiplicidad de “plataformas”, aunque ni las fotos ni las plataformas tengan significado alguno, multiplicando nada más la avalancha de imágenes disociadas bajo la que vivimos sometidos, y menos normal aún que tomes esas fotografías en lugar de ver lo que estas fotografiando, en lugar de vivir; que no es normal andar (tropezándote) por la calle o en el transporte público como un zombi, sin enterarte de lo que te rodea, sin ver la luz o la oscuridad o la estación del año, ni a la gente a tu alrededor, por estar absorto o absorta en la sordidez de ese desfile inane e interminable de imágenes, videos e información vacua; que no es normal preguntarle a tu aparato todo lo que no sabes o has olvidado, aunque no te interese particularmente saberlo, debido a una neurótica ansiedad que te vuelve incapaz de soportar el silencio, el ritmo natural del tiempo, la incertidumbre o la soledad, sin darte cuenta además de que esta ansiedad te hunde aún más en esa soledad y en la enajenación; que no es normal que en cualquier lugar público estemos a merced del ruido infame de los aparatos de otros que hablan por teléfono, oyen música, partidos de futbol, anuncios o cualquier otra cosa con las bocinas encendidas porque no tienen ninguna noción del respeto al espacio y el silencio ajenos; que no es normal confiar tu vida entera a ese aparato y creer que va a proteger esa vida, ni convertirlo en tu mapa, perdiendo para siempre la oportunidad de perderte y descubrir algo nuevo; que no es normal que a través de ese artilugio y esa tecnología cualquier persona pueda saber el lugar en que te encuentras; que no es normal estar “conectados” 24 horas al día con otros aparatos ni con la “nube”; que no es normal ceder la información sobre nuestra identidad y todos nuestros asuntos a dicha tecnología, y aceptar el espionaje de gobiernos, sistemas de mercadotecnia y cualquier otro canalla sin pensar siquiera en defendernos, sino, por el contrario, entregando dicha información de buena gana; que no es normal creer que ese aparato que no sueltas es tu espejo (no lo es), ni creer que las fotos “optimizadas” que toma gracias a su sofisticada tecnología son la realidad; que no es normal que, mientras trabajas, te asalten ventanas emergentes diciéndote que tu computadora está en riesgo y la tienes que reiniciar o instalarle algún software que no entiendes ni sabes si es bueno o malo, porque no sabes si puedes confiar en el mensaje; ni leer una publicación mientras otras ventanas saltan ante tus ojos anunciando productos o hablando de otra cosa; que no es normal leer, informarte, seguir por ejemplo las noticias de una guerra atroz mientras ese mismo bombardeo de imágenes y discursos tratan de desviar tu atención a otro lugar, convirtiendo lo que lees en espectáculo; que no es normal vivir, trabajar e informarte bajo un constante sistema de distracción de la atención; que no es normal sentir que si pierdes tu teléfono has perdido toda tu vida, estás en riesgo, te has perdido tú, y no darte cuenta de que las pérdidas y el riesgo son, de hecho, producto de tu teléfono inteligente.

Quienes venimos desde el ya remoto siglo XX recordamos muy bien un tiempo en que nada de esta fragmentación, de esta pesadilla, era necesario. Teníamos, sí, nuestros muchos y graves problemas. La famosa canción de King Crimson, cuyo título tomo para estas notas, habla en realidad de ellos, y no de lo que nos tocaría ver en el siglo XXI, porque el autor de la letra, Peter Sinfield, no podría haber imaginado, en 1969, el infierno al que entraríamos voluntariamente, sin quejarnos. Nosotros hemos sido testigos de cómo, de lo útil, de lo novedoso, de lo genial incluso en la nueva tecnología, fuimos resbalando a este estado de alienación y aturdimiento colectivos, primero sin darnos cuenta, y luego sin podernos defender. No es de extrañar que tantas personas busquen ahora en la meditación y en la llamada “atención plena” un asidero para no enloquecer, pero no hay meditación que pueda salvarnos si no apagamos primero el teléfono.

Es curioso cómo protestamos y hacemos campañas en contra de la violencia, del desastre climático, del racismo, de los gobiernos corruptos, de todo tipo de discriminación, de la injusticia y la desigualdad, y sin embargo nadie protesta en contra de esta esclavitud atroz. Vamos dócilmente rumbo al matadero, teléfono en mano.

La dimensión de la pérdida de nuestra humanidad en este mundo fragmentado es indecible, y no es—nunca lo fue—inevitable. La permitimos por molicie, por ignorancia, por frivolidad y por pereza. Ya va siendo hora de despertar: se nos está haciendo tarde.

-Imagen de Fouquier

Adriana Díaz-Enciso es poeta, narradora y traductora. Ha publicado las novelas La sed, Puente del cielo, Odio y Ciudad doliente de Dios, inspirada en los Poemas proféticos de William Blake; los libros de relatos Cuentos de fantasmas y otras mentiras y Con tu corazón y otros cuentos, y seis libros de poesía. Su más reciente publicación, Flint (una elegía y diario de sueños, escrita en inglés) puede encontrarse aquí.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.