A Most Disturbing Book

Rogelio García-Contreras

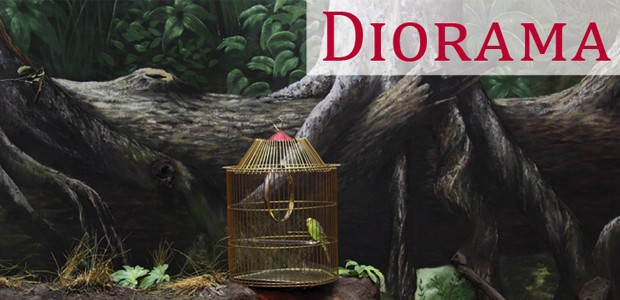

John Gibler,

John Gibler,

To Die in Mexico: Dispatches from Inside the Drug War,

City Lights, 2011.

When I was a kid back in the 1970s, Mexico was going through one of its most dramatic transformations. Almost without noticing, the demographic explosion experienced during the years that followed the massacre of Tlatelolco became one of the country’s most significant and overwhelming problems. During the 1990s, the country reached 90 million people and by the end of the century, we were more than a hundred million. A large percentage of these fairly young population reached their economically active age by the mid 1990s, just in time for another major and recurrent problem present in the country since the early 1980s: the economic crises of the lost generation. From hyperinflation and foreign debt to austerity and unemployment.

The War in Central America, product of the American paranoia and its battle against Communism, contributed to the demographic explosion of the country and complicated the precarious economic circumstances. Corruption, the most democratic condition of Mexico and Mexicans–paraphrasing Carlos Monsivais–was of course the cherry on the cake. Weak governmental institutions, lack of law enforcement, ancient cultural practices related to electoral processes, centralization of power, tax evasion, special favors, poor administration of resources, lack of transparency, impunity, abuse of power: the list is endless and far more endemic and less romantic than the collective image of a citizen bribing a public official or a police officer asking for his “mordida.”

When I was a kid, back in the 1970s, Mexico was already a very corrupt and poor nation. Today, as an adult, I would have to be living in a state of denial for me to believe that such issues have been solved or even controlled. In fact, I may even argue that both, poverty and corruption are much worse in Mexico today than thirty years ago. Corruption for once has become institutional, not in the official collective discourse of the Mexican psyche–in fact, modernity has brought an official rejection of corrupt practices, at least rhetorically–but in the actual actions of its citizens, in the modus operandi of the country. We say one thing, we do another. And when it comes to poverty, well, official figures recognize forty million people suffering from all kind of needs and limitations, lack of opportunities, marginalization, unemployment, lack of education.

When you have no opportunities in the country, a large and ever growing uneducated or undereducated population, no productive investment, a powerful neighbor, a corrupt government, a weak or non-existent democracy, infinite social problems and a series of economic policies that focus more on creating a stable environment for big capital investors than on procuring social justice and equality of opportunity for the citizens of the country, these citizens need to find alternatives. When you have a weak state unable to enforce the law and procure justice in an expedite manner, these alternatives tend to become lawless.

When I was a kid, back in the 1970s, the world described by John Gibler in his book To Die in Mexico didn’t exist. This Mexico is new for me, but I am forty years old. As Serrat would say, twenty years ago I was twenty, and although nothing described in this extraordinary account regarding the state of decomposition of Mexico and Mexican society scares me or surprises me anymore–I guess I am getting used to it–I wonder about the kind of memories that a twenty year old Mexican kid may have of his own country: poverty, corruption, unemployment and, oh, yes, crime, impunity, insecurity in the streets, kidnapping, migration to the North, drug dealing, narco trafficking… the culture of the Narco Corrido.

With no opportunities and a profitable market to the north, the answer is obvious, even if that market is black or illegal. But then again, the memories of these kids will also be permeated by the Mexican Government official response towards the problem: A Drug War. Given our geographic position (unfortunate for many, a blessing for most) we are a ‘transit’ country, to put it in official terms. We are next door to the largest consumer, so the poorest country in the equation, the one with a corrupt government, identified by the powerful neighbor as a country at risk of collapsing, that same country has been chosen by the intelligence and security officials of both nations to be the one in charge of carrying out a frontal attack on the extremely powerful cartels, so that the drugs American consumers demand–in a business

that generates billions of dollars a year–can be confiscated in Mexico and stop polluting American society.

As I read Gibler’s chilling description of this War on Drugs, I question the proud display made by my own government for carrying out this same war. What are we doing? What kind of world are we building for our kids? What are we really accomplishing? The economic crisis has forced us, among other things, to subsidize the American economy with cheap labor. Now it seems that it is forcing us as well to attack this same youth, for whom we have never provided an alternative or a decent opportunity other than this life of crime and corruption. By giving them no alternative but to subsidize–with their own lives and the lives of those that confront them or get in their way–the peaceful lifestyle of American suburbs, we are only deepening the social and moral crisis of the already fractured Mexican society, while helping to maintain the conventional perception that corruption exists only south of the border. After all, if America, the largest consumer of drugs in the world, is not facing the kind of problems Mexico has with drug cartels, it is only because American government agencies and public officials are not as corrupt as their Mexican counterparts, right? Drug dealing is solved by placing a good percentage of the marginalized black and Latino population in prison, serving the Crime Punishment Industry and “dealing” with drug dealing (in poor neighborhoods). Drug trafficking, on the other hand, clearly is a different story, but I am sure the less corrupt American system has a sophisticated (although highly inefficient) operation in place to prevent drugs from being moved from McAllen to Denver once they are trafficked into American territory, don’t they? And finally, the real winners in all this, weapon manufacturers selling their gadgets to criminal organizations and law enforcement agencies. After all, it is a free market.

Am I exaggerating? Just read To Die in Mexico. Dispatches from inside the Drug War, an extraordinary and detailed account of the War on Drugs, its link to the illicit businesses of human and weapon trafficking, and the effects that these state of social disintegration has had on real people –the day-to-day victims of this senseless war. To Die in Mexico is a cruel, sad, chilling, tragic and often disturbing book but it is also a MUST read.

Posted: May 9, 2012 at 6:38 pm