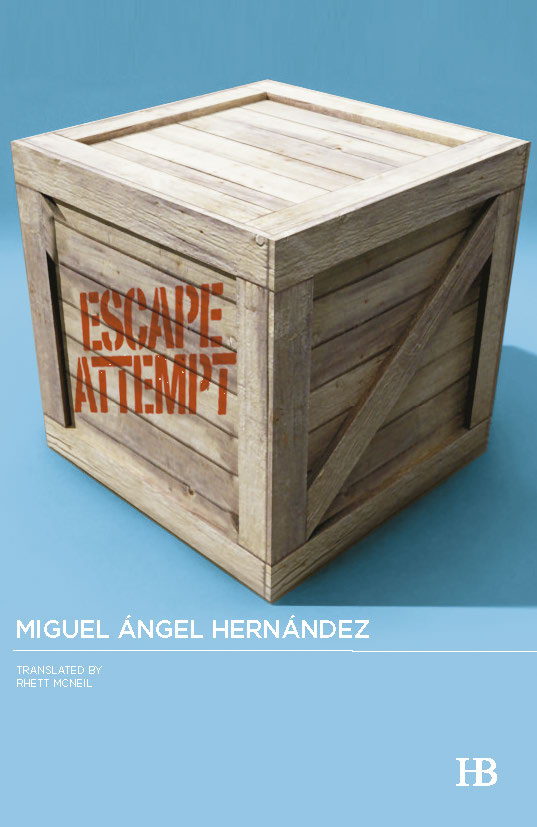

Escape Attempt

MIGUEL ÁNGEL HERNÁNDEZ

Prologue (With Hidden Noise)

Translated by Rhett McNeil

I entered the room covering my mouth with a handkerchief. I could only advance a few meters. The stench was intolerable. The putrefaction penetrated every one of the pores of my skin. My stomach turned, and a bitter taste began to rise in my throat. I closed my eyes and clenched my teeth to keep down the vomit. I tried to hold my breath as long as I could. Five seconds, ten, fifteen, twenty, thirty …a little longer, forty, fifty …until the nausea subsided and my body began to get acclimated. Only then was I able to open my eyes and direct my gaze to the center of the room. And there I was able to see, at last, the box, theatrically illuminated in the midst of the darkness.

The structure, approximately one meter tall by one and a half meters wide, was made of wood and had metal reinforcements at the corners. Next to it were two small screens that played a sequence of moving images. On the first, a person entered the interior of the box. Then someone approached the box and attached the lid on top. This action was repeated on a loop. The second screen displayed the closed box. No one entered or exited from it. The wooden box simply sat there. The same one that emanated the smell that was making my stomach turn. The same one that was right there in front of me, in that exhibition hall in the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. The same one that had next to it a small label on which could be read: Jacobo Montes, Escape Attempt, 2003.

The piece was part of the exhibition that opened the new season at the art center. With Hidden Noise: That Which Art Conceals, more than fifty works from the historical avant-garde to the present day, which intended to demonstrate that art is always concealing something beyond what we can see. Works that were hidden, veiled, crossed out, covered, wrapped, erased, and even destroyed. Duchamp, Manzoni, Morris, Christo, Acconci, Beuys, Richter, Salcedo . . . and at the end of the lineup, as if it couldn’t have been any other way, Jacobo Montes, the great socially engaged contemporary artist.

I had gone to Paris to try to finish a book. The Ministry of Education had given me a travel grant, and my intention was to bring to a close, finally, the research that had kept me occupied for the last ten years of my life: the rupture of visual pleasure in contemporary art. I dedicated my doctoral dissertation to this issue. The majority of my writing since then never ceased to perambulate around the same problem. But it was all scattered about in short articles and essays for catalogues, and I couldn’t find a way to give shape to all that material. After several years of frenetic work, the moment had arrived to bring it all together, rewrite it, and assemble the definitive version of the book. The exhibit was the perfect excuse to start fresh. And the stay in Paris would allow me to dedicate the necessary time to the matter.

I had known for some time that this exhibition was going to open in Paris. And I was able to arrange everything so that my trip would coincide with this event. The fact that a place like the Pompidou was organizing a show about concealment and occultation certified that my work on antivision continued to be relevant. The exhibit fell squarely into the field of my research. Hiding things, removing them from view, is nothing more than frustrating the spectator’s gaze. To conceal, strike through, veil, enclose . . . to rupture visual pleasure.

I went to Paris to write a book. That’s what I told the university. It was also what I told myself. But deep down I knew that this wasn’t totally true. At least not entirely so. There was something more. Something that I clearly knew I would find in that place. Something that was now right in front of me and was making my stomach roil. Jacobo Montes, that indispensable, lauded artist, a fundamental figure of contemporary art. And his masterpiece, Escape Attempt, the one I had sought out so many times, the one that, ten years earlier, I hadn’t had the courage to face, the one that, ever since then, never ceased to trouble me.

I wasn’t alone at the exhibition. Visitors surrounded the box. They circled around it, trying to find meaning for what they saw, imagining what was inside that mysterious object, searching for a connection between the videos that were playing and what was right in front of their eyes; asking themselves, for certain, if the figure who had entered the box had remained there, if the stench of decomposition they could barely stomach had something to do with this body that never revealed itself again. I know that this possibility was passing through their minds, that they might think that something didn’t add up, that at bottom it was all pure contradiction, a game . . . a work of art. I intuited it, recognized the way they looked at it, understood their questions. I had asked myself those questions thousands of times. Again and again. Just like them. Because I didn’t know what was inside that structure either.

But there was something that I did, indeed, know. Something other people didn’t. The history of the box, its past, its origin. I knew this better than all those in the room at that moment. Better than the director of the museum, the curator of the exhibition, the art critics from specialized publications. Better than all of them. And I knew it because I’d been there. Because, sometime before, ten years earlier, I had been the privileged witness of that escape attempt.

At that moment, as I observed the visitors speculating about the thing in front of their eyes, images began to f lood back into my head. And at that instant I became aware that there was something of mine inside there. Even though I was outside the box, my story remained enclosed within it. It was then that I remembered the day on which I’d heard Montes’s name for the first time. The recollection came like a sharp blow. Montes. A hammer strike. A harmful explosion that pulverized my retina. Montes. A scream from within the wood.

And it all unfurled before me.

Like a fan, the past opened itself before me. The end of the 2003 term, Montes, Helena, the city, the lies, the disappointments, the fugitive impressions, the shadow, the escape attempts . . . and Omar, unfortunate Omar. Everything was there, hazy, blurry, voluntarily filed away in a corner of my memory. A dense iconostasis that kept me from distinguishing it clearly. But the vision of the box, the stench, the bitter aftertaste, the repressed vomit, the roiling stomach . . . they all combined on that afternoon to bring things to the present.

A lash from a whip opened the box of images.

And the story started to spring up in my head like an incessant noise. A hidden noise that I no longer knew how to silence.

© Miguel Ángel Hernández: Escape Attempt, Hispabooks Publishing, 2016.

Miguel Ángel Hernández Navarro (Murcia, Spain, 1977) is Associate Professor of Art History at University of Murcia and was formerly the director of the Centro de Documentación y Estudios Avanzados de Arte Contemporáneo (CENDEAC). He focuses on antivisual art, contemporary art theory, migratory aesthetics and memory. He is author of several books on art and visual culture. As a fiction writer he has written a journal, a book of short stories and the novel Escape Attempt, shortlisted in the Premio Herralde de novela, and which has been translated into French, German, Italian, and Portuguese as well as English. He is currently a fellow of the Society for the Humanities at Cornell University.

Miguel Ángel Hernández Navarro (Murcia, Spain, 1977) is Associate Professor of Art History at University of Murcia and was formerly the director of the Centro de Documentación y Estudios Avanzados de Arte Contemporáneo (CENDEAC). He focuses on antivisual art, contemporary art theory, migratory aesthetics and memory. He is author of several books on art and visual culture. As a fiction writer he has written a journal, a book of short stories and the novel Escape Attempt, shortlisted in the Premio Herralde de novela, and which has been translated into French, German, Italian, and Portuguese as well as English. He is currently a fellow of the Society for the Humanities at Cornell University.

Posted: March 10, 2016 at 10:07 pm

Very good post. I absolutely appreciate this site.

Thanks!