Global Immigration

Patricia Gras

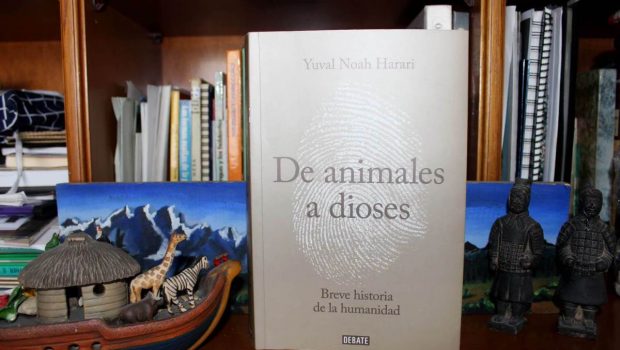

• Otto Santa Ana and Celeste Gonzalez de Bustamante (eds),

Alto Arizona VetoSB 1070. Arizona Firestorm

Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2012.

A lot has been written about the Arizona SB 1070 law, one of the strictest anti-immigration laws ever passed in the United States. On September 5th 2012, a US District Federal Judge Susan Bolton cleared one of the most controversial aspects of the law. Police officers can now request the immigration status on of anyone they suspect is in the country illegally.

The timely anthology, Arizona Firestorm is a comprehensive look at why the law came into effect and, how global migration impacts our immigration patterns, as well as national media coverage of immigration, and local politics. The book is divided into four sections written by 20 twenty contributing authors, including former Aattorney Ggeneral Alberto Gonzalez, and edited by Otto Santa Ana and Celeste Gonzalez de Bustamante. They cover the “Background” of the law and the history of immigration in Arizona; “The Firestorm,” which describes the law in detail and what led to its passing; the ”Mass Media Role” in the immigration debate and, finally, “Prospects,” that is to say, the future impact of globalization in our political and economic life, and looking atconsidering immigrationas to be a global phenomenon.

What this highly well-documented book does wellaccomplishes is to remind readers that immigration is a labor migration issue. Immigrants need work, and employers in the United States desire cheap labor. And this is not just a United States phenomenon: It af- fects the whole world. As Editor Otto Santa Ana points out, “214 million people are on the move, principally for better economic opportunities.”

In the case of Arizona, author Judith Gans dedicates a chapter to explaining the bottom line: immigrants provide a net positive result to the state’s economy. But, the growth among non-citizens in that state created anxiety among locals. “Arizona’s foreign born population grew by more than 300 percent between 1990 and 2004.” They only make up only 14 percent of the population but, apparently, they make the locals uncomfortable. Many natives complain that there is a “Mexican invasion” that is ruining Arizona.

Several authors expose how certain laws have represented a desire to maintain cultural and demographic dominance overf the locals by punishing school districts which “may be promoting the overthrow of the government” (later proven untrue) eliminating programs that open all students to civil rights education, or handing down the 2010 edict that Arizona schools may certify that their teachers do not speak English with an “accent.” Not to mention the desire expressed by many to modify the 14th amendment of the US Constitution, which grants citizenship to all children born iin US soil.

The book is highly critical of the US mass media for its lack of historical context, unbiased information and in-depth analysis of the law. This includes Spanish-speaking media, which has often played the role of advocate, while countering the negative stereotypes of immigrants found in most English language media.

Marcelo Suarez Orozco and Carola Suarez Orozco wrote one of the most enlightening chapters, “Immigration in the Age of Global Vertigo,” which offers some of the best explanations of the socio-economic and historical context that led to the controversial law, shattering so many of the myths about undocumented immigrants.

Arizona Firestorm is a must read for anyone interested in public policy, students, scholars and reporters who want to understand the facts and realities of immigration in our nation, seldom heard in the public forum.

Posted: January 7, 2013 at 4:21 am