The morning after

LA MAÑANA DESPUÉS

Cristina Rivera Garza

Translated by Cheyla Samuelson

It’s a grey morning in the Second Ward, the most traditional Mexican barrio in Houston, Texas. It is also an unnervingly quiet morning. The neighbor across the way, who usually comes out shirtless to hang out clothes, has broken his routine. The sounds of motors and footsteps are also missing. The radios, which usually invade the space with songs or interviews, have been silenced. The lonely streets, lined with motionless walnut trees, let pass unchecked the cold wind that announces the still subtle presence of winter. It is a war zone. It feels like a war zone after everything has been lost. It is the morning of November 9th, 2016, and against all expectations, Donald Trump has won the presidency of the United States.

How does it feel? It feels like shit.

There are questions, also silent, when faces start to appear on the sidewalks, at the bus stops, in the classrooms and the offices. The buried vulnerability of those who feel exposed. The gaze that can’t yet understand. My colleagues, my professors, my neighbors, the people that I pass in the street every morning or every afternoon, ¿Did they vote against me? The question could be innocent, if it weren’t terrifying. The white vote, by white men and women with and without education but ready to do anything to preserve their privilege answers yes, yes in fact, they voted against you. The vote of the white working class, which saw their jobs in heavy industry disappear owing to NAFTA and the swift effects of neoliberalism answers yes: I voted against you. What are we going to do when we see each other in supermarkets and banks, at family gatherings, at the entrance to school, at the gym? How can we look each other in the eye, knowing what we now know, what has become chillingly clear?

Because one thing is true: The ethic and racial diversity of the United States is irreversible. We are going to keep seeing each other and keep encountering each other in the same places where, until today, a certain civility has existed, sometimes a clumsy one, sometimes tentative and often conflicted, but always dynamic. The 14.99 million Latinos that, according to the census, live in California, and are the largest demographic there since June 1st, 2015, are not going to disappear. My son, who yesterday went out to vote for, among other things, the proposition that made legal the recreational use of marijuana, asks: Would it be better to leave? I don’t hesitate to tell him no. To tell him that we will stay here. To tell him that this has been our country for at least three generations. To tell him that our work gives us the right to have a life as happy and full as anyone else here. To tell him that we can’t think about fleeing, but rather about building. To tell him we have to protect our strongholds, and put ourselves in contact with our others in order to continue building vital and resilient communities.

And this is what we do at work, where we all arrive with eyes still full of fear from the nightmare, and the fear of the reality. It’s an emergency meeting to plan the strategies that we will have to put into action if we want our projects and our programs to continue receiving the resources that we have won, thanks to the fight of entire generations of Mexicans, Mexican Americans, Latinos and Chicanos who have made this university a Hispanic Serving Institution. The terror presses down on us, but what lifts our spirits is the speed with which ideas arise and the urgency with which each one of us goes immediately out to do their work, as if time was running out and we were risking our lives.

Time is running out and we are risking our lives.

Or maybe it’s the opposite, perhaps time is starting and we are taking life very seriously. I have had so little confidence in a democracy of the powerful for the powerful. And I am convinced that the devotion of neoliberalism to profit is more or less shared by all the parties in play. What we lose in this moment when the mask is removed is not democracy or equality, but rather the façade behind which we have been offered a bad deal as if it were a good one. When the enemy reveals its face in such an obvious manner, when things say their name with no shame and without the veil of good manners, it is the moment to show our true face as well. It is called living in resistance. It’s called searching among the debris of the morning after for our others in order to imagine the unimaginable: The world we wish to live in.

Hard times are coming for us, without a doubt. But also for them.

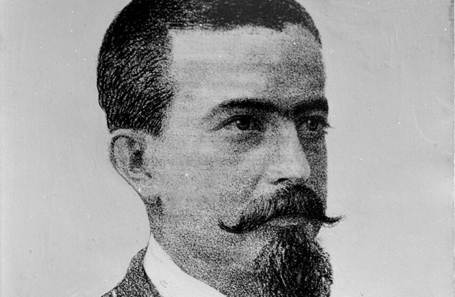

Cristina Rivera Garza is a Mexican author and professor best known for her fictional work, with various novels such as Nadie me verá llorar winning a number of Mexico’s highest literary awards as well as awards abroad. She is a regular contributor of Literal Magazine via her column Overcast. (Author´s image by Santiago Vaquera)

Cristina Rivera Garza is a Mexican author and professor best known for her fictional work, with various novels such as Nadie me verá llorar winning a number of Mexico’s highest literary awards as well as awards abroad. She is a regular contributor of Literal Magazine via her column Overcast. (Author´s image by Santiago Vaquera)

©Literal Publishing

Es una mañana gris en el Second Ward, el barrio mexicano de más tradición en Houston, Texas. Es, también, una mañana apabullantemente silenciosa. El vecino de enfrente, que por lo regular sale sin camisa a tender algo de ropa, ha roto su rutina. Los ruidos de motores o de pasos tampoco se dejan oír. Los radios, que con frecuencia invaden el espacio con canciones o entrevistas, han enmudecido. Las calles solas, bordeadas de altos nogales inmóviles, dejan pasar a su antojo el viento frío que anuncia la presencia todavía sutil del invierno. Es una zona de guerra. Parece una zona después de la guerra cuando ya todo se ha perdido. Es la mañana del 9 de noviembre de 2016 y Donald Trump ha ganado, contra toda expectativa, la presidencia de los Estados Unidos.

¿Qué se siente? Se siente de la chingada.

Hay preguntas, también mudas, cuando los rostros empiezan a hacer su aparición sobre las banquetas, en las paradas de autobús, en los salones de clase y las oficinas. Esa soterrada vulnerabilidad del que se sabe expuesto. La mirada del que no acaba de entender. Mis colegas, mis profesores, mis vecinos, la gente con la que me cruzo cada mañana o cada tarde, ¿votaron contra mí? La pregunta podría ser inocente si no fuera terrorífica. El voto blanco, de mujeres y hombres blancos, con y sin educación pero dispuestos a todo con tal de preservar su privilegio, contesta que, sí, en efecto, votaron contra ti. El voto de la clase trabajadora también blanca que vio desaparecer sus empleos en la industria pesada conforme se afianzaba el NAFTA y, con él, la secuela voraz del neoliberalismo, contesta que sí. Voté en contra tuyo. ¿Qué vamos a hacer cuando nos veamos en los supermercados y en los bancos, en las reuniones de padres de familia, a la salida de las escuelas, en los gimnasios? ¿Cómo vamos a poder mirarnos frente a frente sabiendo lo que ya sabemos, lo que nos ha quedado escalofriantemente claro?

Porque una cosa es obvia: la diversidad étnica y racial de los Estados Unidos es irreversible. Nos vamos a seguir viendo y vamos a seguir encontrándonos en los mismos sitios donde se ha llevado a cabo hasta hoy una socialidad a veces torpe y a veces tentativa, con frecuencia conflictiva, pero siempre dinámica. Los 14.99 millones de latinos que, de acuerdo al censo, viven en California, son mayoría demográfica desde el primero de Julio del 2015 y no van a dejar de existir. ¿Y si mejor nos vamos?, me pregunta mi hijo quien, ayer, como todos sus amigos, salió a votar, entre otras cosas para apoyar la moción que volvió legal el consumo de marihuana con fines recreativos. Y no dudo al decirle que no. Al decirle que nos quedamos. Al decirle que este es nuestro país desde, al menos, tres generaciones atrás. Al decirle que tenemos el derecho que nos da nuestro trabajo a tener una vida tan feliz y plena como la de cualquier otro. Al decirle que no pensemos en huir, sino en construir. Al decirle que tenemos que resguardar nuestros fuertes y ponernos en contacto con nuestros otros para seguir formando comunidades vivas y tercas.

Y esto es lo que hacemos en la oficina a la que llegamos todos con los ojos todavía llenos del espanto de la pesadilla y del espanto de la realidad. Es una reunión de emergencia para planear las estrategias que tendremos que poner en marcha si queremos que nuestros proyectos y nuestros programas continúen recibiendo los recursos que nos hemos ganado gracias a batallas de generaciones enteras de mexicanos, mexico-americanos, latinos y chicanos que hicieron de la universidad una Hispanic Serving Institution. El terror nos conmina pero lo que nos da ánimo es la velocidad con la que surgen las ideas y la premura con la que cada quien sale a cumplir su tarea de inmediato, como si el tiempo se acabara y nos estuviéramos jugando la vida.

El tiempo se nos acaba y nos estamos jugando la vida.

O tal vez es lo contrario: tal vez el tiempo empieza y nos estamos tomando a la vida muy en serio. He tenido poca confianza en una democracia de poderosos para poderosos. Y estoy convencida que la devoción neoliberal por la ganancia es compartida con mayor o menor cinismo por los partidos en contienda. Lo que perdemos en este momento de quitarse las máscaras no es la democracia ni la igualdad, sino el barniz con el que se nos ha ofrecido la mejor parte de un mal trato como si fuera un buen trato. Cuando el enemigo se descubre el rostro de manera tan evidente, cuando las cosas se dicen por su nombre sin miramiento alguno y sin el velo de las buenas costumbres, es el momento de mostrar el rostro verdadero a su vez. Se llama vivir en resistencia. Se llama buscar entre la desolación de la mañana después, a los otros de nuestros otros para imaginar lo inimaginable: el mundo en el que queremos vivir.

Se vienen tiempos difíciles para nosotros, en efecto. También para ellos.

Cristina Rivera Garza es la autora de Nadie me verá llorar (México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 1999), La cresta de Ilión (México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 2002), La muerte me da (México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 2007), Dolerse. Textos desde un país herido (Mexico: Sur+, 2011), entre muchos otros. Es columnista en Literal Magazine . (Fotografía: Santiago Vaquera)

Cristina Rivera Garza es la autora de Nadie me verá llorar (México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 1999), La cresta de Ilión (México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 2002), La muerte me da (México/Barcelona: Tusquets, 2007), Dolerse. Textos desde un país herido (Mexico: Sur+, 2011), entre muchos otros. Es columnista en Literal Magazine . (Fotografía: Santiago Vaquera)

© Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.