Power and Painting

Pintura y poder

Yvon Grenier

Mexico has historically been a rich laboratory to study the linkages between art and politics. For good or bad, political art is probably the best known Mexican art outside of Mexico.

And yet, one of the most interesting case of a politically committed artist is usually overlooked, even in Mexico: the case of Mexican painter Vladimir Kibaltchich, better known as Vlady (Petrograd, 1920 – Mexico city, 2005).

Vlady is an interesting case for numerous reasons. To begin with, he is, in my own amateurish and subjective judgment, as great a painter as any of the best known Mexican painters of his generation. But more to the point I am making here, his art offers an inspiring contrast to the two main artistic currents of his time: to simplify, the didactic political art of the Muralists on one hand, and the non-explicitly political and nonfi- gurative art of their successors, on the other hand. Vlady was an outsider, both artistically and politically, who nonetheless found himself at the intersection of the artistic, cultural, intellectual and political fields in the second half of twentieth century Mexico. His work and itinerary represent a unique vantage point from which to examine what Tocqueville called les passions générales et dominantes of his time. Finally, many of Vlady’s “political” paintings (he would not call them this way: I do) constitute powerful illustrations of how far an artist can go working with political themes while exploiting to the fullest both the enchanting and the dystopian possibilities of art.

In and Out. An Outsider at the Crossroad

The son of Belgium-born Russian writer and dissident Victor Serge (1840-1947), Vlady emigrated from France to Mexico with his father.

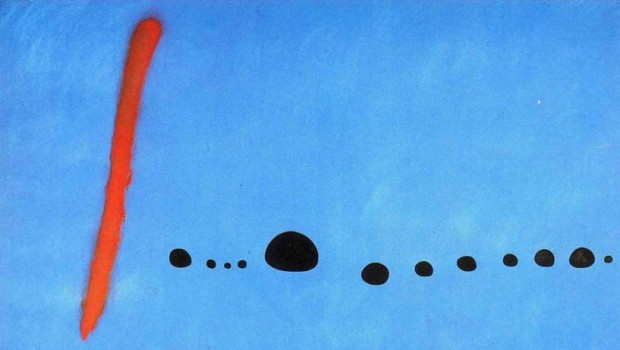

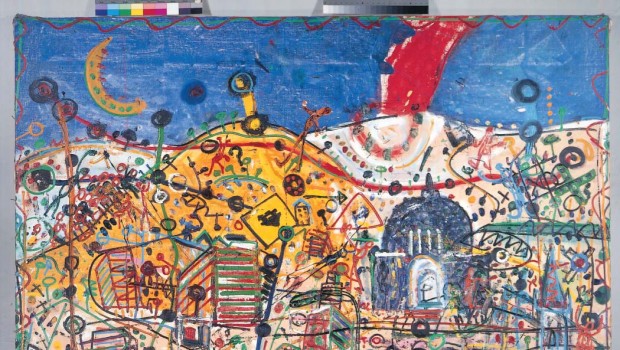

He became a Mexican citizen in1949 and spent the rest of his life in that country. If one assumes for a moment that his oil paintings constitute his most important work (one does not have to make that assumption: his etchings are fabulous), then it is probably fair to say that his most important work is obsessively political. One could mention several masterpieces, starting with the colossal mural Revoluciones y los elementos (1974-82), dedicated to his father Victor Serge. This mural (2,000 m² of paintings, accomplished between 1974 and 1982 in the Ministry of Finance’s Miguel Lerdo de Tejada Library) contains multiple murals-episodes on what Vlady called the English, French, American, Christian, Musical and Sexual revolutions, as well as a gem entitled La inocencia terrorista. Other magnificent paintings include: the mural Xerxes (1974-1990), a personal interpretation of Persian Emperor ordering his troops to punish the sea; the enigmatic mural Herejia (Heresy, 1987) in the Government National Palace in Managua, Nicaragua; four oil paintings commissioned by the Ministry of the Interior of Mexico in 1994 (Violencias fraternas, El general, El uno no camina sin el otro, Caida y descendimiento), and interestingly, almost immediately “sequestered” in the old Lecumberri prison, because apparently the government authorities interpreted them as a tribute to the Zapatista rebellion; the magnificent Trotsky Triptych (three oil paintings: Magiografía Bolchevique, La Casa and El Instante); the constantly reworked Escuelas de los verdugos (1947- 2005); and portraits of Archbishop of Chiapas Samuel Ruiz (Tatic, 1997) and Emiliano Zapata (1998) (the very best portrait of Zapata I have ever seen), the latter commissioned by the government of Puebla, Mexico.

It is important to notice that in Vlady’s paintings, politics appears as a source of artistic inspiration: it is never an overarching goal, and painting is never a means to a political end. The goal of painting is painting: pintura pintura, as Vlady said.

Vlady carefully studied the work of the muralists (especially Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco) and was initially thrilled by some of the work of the “Mexican School of Painting” (as we all know, led by the famous three muralists: Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco). Characterized by a “clear readability of style and unproblematic assimilation of content”, this school dominated the artistic scene until the late 1950s, when it was challenged by a new “generation” of painters determined to break free from the muralists’ straitjacket. Known as the Generación de la ruptura, this group strove to emancipate painters from the official mission to produce didactic, nationalistic and revolutionary (in the political sense) art. Most took this opening as an opportunity to turn their back on “political art” and even figurative art. The result is a production that, in its best rendition, remains profoundly attached to Mexico’s history and artistic tradition (think about the fabulous oeuvre of a Tamayo for instance), but no longer via overt political or “nation-building” lenses.

Soon Vlady “ruptured” from this “generation of rupture”, remaining committed to free and cosmopolitan art while continuing his artistic exploration of historical and political themes, especially “revolution”. Henceforth, Vlady’s art sat uneasily between two great generations of painters, the muralists and the post-muralists. This reminds me a thesis defended by French sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Alain Darbel, in a study on public appreciation of museums. They propose a distinction between “classical periods” and “periods of rupture”, suggesting that to be associated with the latter negatively affects the lisibilité (readability) of one’s oeuvre. The public, and probably the art critiques that shape its perceptions, like to find in artistic works the familiarity of a period, a trend, a “school”, a tradition—even what Octavio Paz would call, referring to modernity, a “tradition of rupture”. With Vlady, this was highly problematic. For all his connections to both the Muralists and to their opponents, Vlady did not fit in and could not easily be “read” by his contemporaries.

Politically, Vlady was considered a Trotskyite; ergo, in view of his attachment to his time and place, he was (again) both in (the revolutionary left) and out (definitely the wrong camp within the revolutionary left). Of course, Vlady’s political commitment was a great deal more complex than that. His peculiar fascination for the persona of Trotsky stemmed not merely from political principles but also from deep emotional ties to his father, to mother Russia, and to personal memories revolution, war, exile and persecution. Vlady was not a political activist or a man of the party in a conventional sense.

Painting Revolution in Post-Revolutionary Mexico

Mexican poet and intellectual Octavio Paz once said that modern Mexican painting is the result of the confluence of “two revolutions: the social revolution of Mexico and the artistic revolution of the West”. For Vlady, one would have to revise this equation. Using a useful distinction proposed by Milan Kundera, between le petit contexte (the historical environment) and le grand contexte (what really matters: the realm of art and its own distinctive traditions), I would mention for the first the political revolution in Russia, the intellectual revolution in Europe (Marx, Freud, Nietzsche) and to a lesser extent the social revolution in Mexico; and for the second, first and foremost, the great paintings of the Renaissance, not so much the “artistic revolution in the West”, if by that one means modernist and avant-garde trends, which Vlady rejected. The muse of Revolution remains a common anchorage, however. One cannot say that he conceived this obsession in Mexico, though it may not be a coincidence if he adopted a country whose modern identity is so dependent on the idea (and myth) of revolution

While an enthusiastic observer of revolutions (in Russia, Mexico, Nicaragua) as well as a compagnon de route of revolts (in Chiapas notably), none of his paintings really promote a particular type of political mobilization or programmatic beliefs, not even revolution (not unambiguously any way). The epicentre of his explorations of revolution is to be found in his own family (the Kibaltchich have time-honoured revolutionary credentials back home in Russia), in the “betrayed” revolution in Russia, and then in Mexico and the rest of Latin America.

Vlady prefers to question himself and history about revolution, blurring the private and the public and looking for signs of timelessness in history. All of this comes out in his paintings, not in his (scattered) written texts, which read like textual translations of non-textual (images, colors) “ideas”.

In sum, Vlady proposes nothing else than an artistic exploration of the revolutionary phenomenon. What does it teach us about revolutions? That revolutions are about both liberty and power, and that these two objectives are largely incompatible. No Manichean narrative of revolution is to be found in Vlady’s work, because good and evil cannot be completely untangled. Man is in history and history is a tragedy, because the human condition is a tragedy.

What is to be done? Trying to be free. Some of his political role models—Trotsky, the Che—were blessed by defeat and sacrifice, though only after a journey in power that arguably cast umbrage on their aura as humanist revolutionaries. Their tragic ends redeemed their true nature as romantic pursuers of the u topos. In the quest for freedom, politics is not the only path: in his Revolución y los elementos, Vlady explores the themes of musical revolution and Freudian revolution. Eroticism is a dominant theme in his work.

The Visible Hand of the PRI

Some of Vlady’s political paintings were commission- ned by governments of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), most notably the colossal Revolución y los elementos. This oeuvre, like most of the other ones commissioned by the government (with the possible exception of the Zapata), is far too enigmatic and critical of power to lend itself to propagandistic use. This begs the question: why would either side agree to this arrangement? Arguably the government approached him and others at a time when the revolutionary aura of the PRI regime had disappeared or was rapidly fading. «Anti-popular regimes foster spectacular demagogic public art”, as David Alfaro Siqueiros once said (and he should know). Clearly, Vlady’s murals are not demagogic, but they are political murals, on the theme of revolution, so perhaps from government officials’ perspective, that was better than no murals (or nonpolitical murals) at all, for in some ways it constituted a public engagement with a key legitimizing myth of the regime, from what they perceived as an ultra-leftist perspective. (After all, the Bolsheviks found some use for Alexander Blok’s hazy poem The Twelve in the early days of the revolutionary regime.) The odd fact that the premise (the 18th century baroque chapel San Felipe!) is used for the Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público’s public library suggests that the full story on this commission would probably give due recognition to the dreary role of individuals, bureaucracy and accidents, rather than grand schemes featuring grand scheme, Machiavellian politics and the judgment of history. It is well known that PRI administrations co-opted artists and writers: the detailed history of how this was done remain to be written.

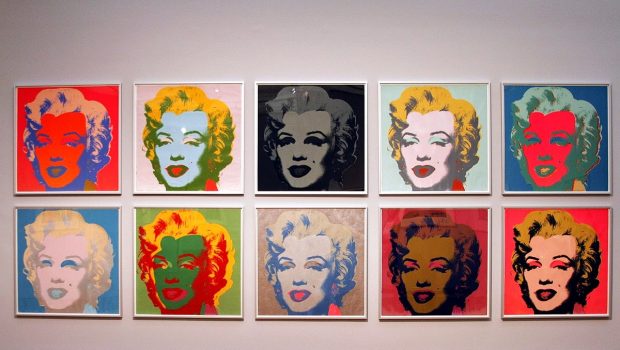

Turning the arrow in the other direction: In keeping with both his artistic and political dispositions, Vlady preferred to have a public rather than a private patron. No patron is perfect, and no patronage is not a practical option. His antipathy to private galleries, commercial art and capitalism was notorious. Here his leftist dispositions met time-honoured Romantic cult of disinterest. Picasso once remarked that painters are typically less politicized than writers. This is true for Mexican painters, who have been much less critical of the government officials and policies than writers. Granted, Vlady accepted government commissions when it was no longer deemed irreproachable to do so. But I doubt that his acceptance of government contracts constituted a major factor explaining his artistic as well as political marginalization in Mexico.

The Art of Political Art

The liaison between art and politics is so obvious in Latin America that one can be forgiven to overlook how complicated and paradoxical their relations can be. Art is routinely conceptualized as a vehicle to transmit political messages, in historical conditions (democratic deficit, marginalization of the majority, cultural elitism) that make this pattern of transmission probable and efficacious. Yet, some questions typically remain unexplored, such as: where exactly is the political in art? Is it to be found in the “content”, the “form” (i.e. “content of the form”), in our interpretation of it, or in some combination thereof? In what sense can we say, as writers and artists routinely do, that great art is necessarily critical of societies and governments? Is art still critical, as all great art should presumably be, when it serves a political ideology, a political actor, even a government? These are tough questions to answer, namely because generalizations on such critical matters are perilous. A good way to make progress is to take a close look at one (or a few) specific cases, grappling with, rather than leveling, the uniqueness that typifies great art in all its inclinations (including political). The case briefly examined here suggests that political art is at its most powerful when art remains “on top”, questioning politics rather than being merely used by it. In his art, Vlady’s politics is a daunting, telluric force (in comparison, Picasso’s politics seems a nature morte, an estheticized depiction of misfortune and tragedy). Only an exceptional artistic vocation could have harnessed such a powerful impulse. The outcome is a pure intensity, one that is perhaps too difficult to withstand, in these soporific times of ours.

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

Uno de los ejemplos más interesantes —el de un artista políticamente comprometido—, es usualmente pasado por alto, aun en México. Tal es el caso del pintor mexicano Vladimir Kibaltchich, mejor conocido como Vlady (Petrogrado, 1920 – ciudad de México, 2005).

Vlady es un caso interesante por muchas razones. A mi juicio —amateur y subjetivo—, él es un pintor tan importante como cualquiera de los pintores de su generación. Más aún, su arte ofrece un contraste inspirador ante las dos corrientes sobresalientes de su época: para simplificar, por un lado, el del arte políticodidáctico de los muralistas y, por el otro, el del arte no explícitamente político ni figurativo de sus sucesores. Vlady era un extraño en su propio entorno —tanto en lo artístico como en lo político—; no obstante, se encontró situado en la intersección de los campos artísticos, culturales, intelectuales y políticos de la segunda mitad del siglo XX mexicano. Su trabajo e itinerario representan una perspectiva privilegiada a partir de la cual se puede examinar aquello que Tocqueville llamó les passions générales et dominantes de su tiempo. Finalmente, muchas de sus pinturas “políticas” (él no las habría llamado de esa manera, yo sí), constituyen poderosas ilustraciones de lo lejos que puede llegar un artista trabajando con temas políticos, explotando, a la vez, ambas posibilidades del arte: el encantamiento y la crítica de la anti-utopía.

Dentro y fuera. Un forastero en la encrucijada

Hijo de Víctor Serge (1840-1947) —escritor disidente ruso nacido en Bélgica—, Vlady emigra de Francia a México con su padre. En 1949 adquirió la nacionalidad mexicana y pasó el resto de su vida en aquel país.

Si se considera, por un momento, que sus pinturas al óleo constituyen lo más importante de su obra (aunque uno no debe darlo por sentado pues sus dibujos son fabulosos), entonces sería justo decir, probablemente, que su trabajo más importante fue obsesivamente político. Se pueden mencionar varias obras maestras, empezando por el mural colosal Revoluciones y los elementos (1974-82), dedicado a su padre Víctor Serge. Este mural (2,000m² de pinturas realizadas entre 1974 y 1982 en la biblioteca del secretario de Finanzas, Miguel Lerdo de Tejada), contiene numerosos episodios de aquello que Vlady llamó las revoluciones inglesa, francesa, americana, cristiana, musical y sexual; así como también la joya titulada La inocencia terrorista. Otras de sus magníficas obras incluyen el mural Xerxes (1974-1990), una interpretación personal del emperador persa ordenando a sus tropas castigar al mar; el enigmático mural Herejía (1987) en el Palacio Nacional de Gobierno de Managua, Nicaragua; cuatro pinturas al óleo encargadas por el Secretario de Gobernación mexicano en 1994 (Violencias fraternas, El general, El uno no camina sin el otro, Caída y descendimiento) que, curiosamente, de manera casi inmediata fueron “secuestradas” en la vieja prisión de Lecumberri, pues aparentemente las autoridades gubernamentales interpretaron estas cuatro obras como un tributo a la rebelión zapatista; el magnífico tríptico Trotsky (tres pinturas al óleo: Magiografía bolchevique, La casa y El instante); el constantemente reelaborado Escuelas de los verdugos (1947-2005); los retratos del Arzobispo de Chiapas, Samuel Ruiz (Tatic, 1997) y Emiliano Zapata (1998) —el mejor retrato de Zapata que yo haya visto—, solicitado, este último, por el gobierno del Estado de Puebla, México.

Es importante hacer notar que en las pinturas de Vlady la política aparece como un recurso de inspiración artística, no como una meta, pues pintar nunca es para él un medio con fines políticos. El objetivo de pintar es pintar: “pintura, pintura”, como él decía.

Vlady estudió con cuidado el trabajo de los muralistas (especialmente Diego Rivera y José Clemente Orozco) e, inicialmente, se sintió entusiasmado por el trabajo de la “Escuela Mexicana de Pintura” (que, como todos sabemos, estaba dirigida por los tres famosos muralistas: Rivera, Siqueiros y Orozco). Caracterizada por una “clara legibilidad estilística y una asimilación del contenido nada problemática”, esta escuela dominó el escenario artístico hasta el final de los cincuenta, cuando fue desafiada por una nueva generación de pintores determinados a liberarse de la camisa de fuerza de los muralistas. Conocidos como “La generación de la ruptura”, este grupo luchó por la emancipación de los pintores de la misión oficial de producir arte didáctico, nacionalista y revolucionario (en el sentido político). La mayoría vio en esta apertura una oportunidad para dar la espalda al “arte político” e incluso al arte figurativo. El resultado es una producción que, en sus mejores ejemplos, permanece profundamente ligada a la historia de México y a su tradición artística (la fabulosa obra de Tamayo, por ejemplo) pero no a través del lente de una política abierta ni del proyecto de construcción nacional.

Muy pronto Vlady rompería con la “Generación de la ruptura” permaneciendo comprometido con el arte libre y cosmopolita, mientras continuaba su exploración artística de temas históricos y políticos, especialmente el de “la revolución”. En adelante, el arte de Vlady se ubicaría, de manera inquietante, entre dos grandes generaciones de pintores: los muralistas y los post muralistas.

Esto me recuerda la tesis defendida por los sociólogos franceses Pierre Bourdieu y Alain Darbel, en su estudio de la apreciación pública de los museos. Proponían una distinción entre los “periodos clásicos” y los “periodos de ruptura”, sugiriendo que la asociación con estos últimos afecta de manera negativa la lisibilité (la legibilidad) de la propia obra. El público y, probablemente, los críticos de arte —quienes modelan sus percepciones— gustan de encontrar en las producciones artísticas la familiaridad de un periodo, una tendencia, una “escuela”, una tradición —incluso lo que Octavio Paz llamaría, refiriéndose a la modernidad, como la “tradición de la ruptura”. Con Vlady esto resultó muy problemático. Debido a sus conexiones con ambos —los muralistas y sus opositores—, Vlady no encajó y no pudo ser “leído” fácilmente por sus contemporáneos.

Políticamente hablando, Vlady fue considerado trotskista; ergo, en vista del apego a su época y lugar, se situó (nuevamente) dentro (de la izquierda revolucionaria) y fuera (definitivamente en el lugar incorrecto, dentro de la izquierda misma). Desde luego, el compromiso político de Vlady era mucho más complejo que eso. Su fascinación personal por lo que Trotsky representaba, provenía no sólo de los principios políticos de aquél sino de las profundas ligas emocionales con su padre, la madre patria Rusia, su memoria personal de la revolución, la guerra, el exilio y la persecución. Vlady no fue un activista político o un hombre de partido en un sentido convencional.

Pintando la Revolución en un México post-revolucionario

El poeta e intelectual mexicano Octavio Paz dijo una vez que “la pintura mexicana moderna es el resultado de la confluencia de dos revoluciones: la revolución social de México y la revolución artística de Occidente”. En el caso de Vlady, uno debería revisar esta ecuación. Haciendo uso de una útil distinción propuesta por Milan Kundera, entre le petit contexte (el entorno histórico) y le grand contexte (el que realmente importa, el reino del arte y de sus tradiciones distintivas propias), yo mencionaría, dentro del petit contexte, la revolución política rusa, la revolución intelectual en Europa (Marx, Freud, Nietzsche) y, de menor trascendencia, la revolución social en México. Dentro del grand contexte, considero, antes que otra cosa, las grandes pinturas del Renacimiento, no tanto “la revolución artística de Occidente”, si por ésta se entiende las tendencias modernas y de vanguardia, que Vlady rechazó. La musa de la Revolución permanece, sin embargo, como un anclaje común. Uno no puede decir que Vlady concibió esta obsesión en México, aunque tal vez no sea una coincidencia que haya adoptado un país cuya identidad moderna sea tan dependiente de la idea (y del mito) de la revolución.

Como un entusiasta observador de las revoluciones (en Rusia, México y Nicaragua), tanto como compagnon de route de los levantamientos (especialmente en Chiapas), ninguna de sus pinturas promueve un tipo particular de movilización política ni creencias programáticas (al menos no sin ambigüedad) El epicentro de sus exploraciones sobre la revolución debe encontrarse en su propia familia (los Kibaltchich tienen credenciales revolucionarias honorables de tiempo atrás en su país, Rusia), en la “traicionada” revolución rusa y, después, en México y en el resto de América Latina.

Vlady prefiere preguntarse a sí mismo y a la historia acerca de la revolución desdibujando lo público y lo privado y buscando los signos de lo atemporal en la historia. Todo esto surge en sus pinturas, no en sus escasos textos escritos, que se “leen” como traducciones textuales de “ideas” no textuales (imágenes y colores).

En suma, Vlady no propone más que una exploración artística del fenómeno revolucionario. ¿Qué nos enseñan las revoluciones? Que tienen que ver con el poder y la libertad, y que ambos objetivos son ampliamente incompatibles. Ninguna narrativa maniquea de la revolución se puede encontrar en el trabajo de Vlady, porque el bien y el mal no pueden desligarse del todo. El hombre está en la Historia y la Historia es una tragedia porque la condición humana es una tragedia.

¿Qué debe hacerse? Tratar de ser libres. Algunos de sus modelos políticos —Trotsky, el Che— fueron bendecidos por la derrota y el sacrificio, aunque sólo después de una jornada en el poder que sustenta el ensombrecimiento de su aura como humanistas revolucionarios. Sus trágicos fines redimieron su auténtica naturaleza de perseguidores románticos del utopos. En la búsqueda de la libertad, la política no es el único camino: en su Revolución y los elementos, Vlady explora los temas de la revolución musical y de la revolución freudiana. El erotismo es un tema dominante en su trabajo.

La mano visible del PRI

Algunas de las pinturas políticas de Vlady fueron encargadas por gobiernos del Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), particularmente la obra colosal Revolución y los elementos. Ésta, como la mayoría de las obras solicitadas por el gobierno (probablemente con la excepción de Zapata), es demasiado enigmática y crítica del poder para ofrecerse como material de uso propagandístico. Lo que hace necesaria la pregunta: ¿por qué cada una de ambas partes aceptaría este acuerdo? Puede argumentarse que el gobierno se acercó a él y a otros en un tiempo en que el aura revolucionaria del PRI había desaparecido o se estaba disolviendo con rapidez. “Los regímenes anti-populares promueven arte público demagógico y espectacular”, como David Alfaro Siqueiros dijo alguna vez (y él sí lo sabía). Evidentemente, los murales de Vlady no son demagógicos, pero son murales políticos sobre la revolución, así que, probablemente desde la perspectiva de los funcionarios, esto era mejor que la falta absoluta de murales (o de murales “no políticos”), pues de algún modo ello constituía un compromiso con un mito toral del régimen, acerca de lo que ellos percibían como una perspectiva de ultra izquierda. (Después de todo, los bolcheviques encontraron alguna utilidad al nebuloso poema de Alexander Blok, Los doce, en los primeros tiempos del régimen revolucionario). El hecho extraño de que la propiedad — ¡la capilla barroca de San Felipe, del siglo XVIII!—, se usara para instalar la biblioteca pública de la Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, sugiere que la historia cabal de esta comisión daría, probablemente, el debido reconocimiento al monótono papel de los individuos —la burocracia y sus circunstancias—, más que a la presentación de El Gran Programa, las políticas maquiavélicas y el juicio de la Historia. Es bien sabido que las administraciones priístas cooptaron artistas y escritores, pero la historia detallada de cómo ocurrió está por escribirse.

En lo que a sus disposiciones artísticas y políticas se refiere, Vlady prefirió tener un patrón público antes que uno privado. Ninguno es perfecto, pero la ausencia de patronazgo tampoco es una opción práctica. Su antipatía por las galerías privadas, el arte comercial y el capitalismo, fue notable. Su natural disposición a la izquierda y su —por largo tiempo honrado— culto romántico al desinterés, coincidieron. Picasso mencionó alguna vez que, en general, los pintores están menos politizados que los escritores. Esto es cierto en el caso de los pintores mexicanos, quienes han sido menos críticos de los funcionarios gubernamentales y sus reglas que los escritores. Desde luego, Vlady aceptó encargos del gobierno cuando ya no se consideraba irreprochable hacerlo. Pero dudo que aceptar los contratos gubernamentales constituyera un factor relevante para que se le marginara en el campo artístico y político de México.

El arte del arte político

La relación entre el arte y la política es tan obvia en América Latina que a uno puede perdonársele pasar por alto lo complicadas y paradójicas que estas interrelaciones pueden ser. Generalmente, el arte es concebido como un vehículo para la transmisión de mensajes políticos, en condiciones históricas (déficit democrático, marginación de las mayorías, elitismo cultural) que hacen de éste un modelo de transmisión probo y eficaz.

Sin embargo, algunas preguntas permanecen sin ser exploradas: ¿en dónde, exactamente, está lo político en el arte? ¿Se le debe encontrar en el “contenido”, en la “forma” (en “el contenido de la forma”). En nuestra interpretación de éste o en alguna combinación de lo antes mencionado? ¿En qué sentido podemos decir —como los escritores y los artistas frecuentemente lo hacen—, que el gran arte es necesariamente crítico de las sociedades y de los gobiernos? ¿Puede el arte ser crítico aún —como todo gran arte presumiblemente lo es—, cuando sirve a una ideología política, a un actor político, o incluso a un gobierno? Estas son preguntas difíciles de responder porque las generalizaciones con respecto a estos asuntos críticos son peligrosas. Una buena forma para avanzar en la respuesta es la de mirar con atención a uno (o a varios) casos, integrando, más que nivelando, la singularidad que tipifica al gran arte en todas sus inclinaciones —incluyendo la política. El caso, brevemente analizado aquí, sugiere que el arte político es poderoso, a su máximo potencial, cuando permanece “por encima”, cuestionando a la política y no siendo, tan sólo, utilizado por ésta. En su arte, “la política” de Vlady es una sobrecogedora fuerza telúrica (en comparación, la política de Picasso parece una “naturaleza muerta”, una descripción estatizada del pesar y la tragedia). Sólo una vocación artística excepcional pudo haber ensamblado un impulso tan poderoso. El resultado es una intensidad pura, una intensidad que quizá sea demasiado difícil de resistir, en estas épocas soporíferas nuestras.