The Ritual of Poetry: A Conversation with Miguel Ángel Zapata

El Ritual de la Poesía

Miguel Ildefonso

Translated to English by Angela McEwan

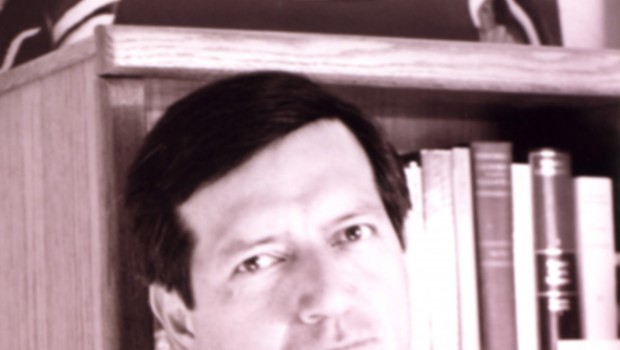

With the publication of El cielo que me escribe (Mexico, 2002), Miguel Ángel Zapata has become a needed and innovative presence in the new Hispanic American poetry, and at the same time, he has also become an authority on the study of contemporary Hispanic American poetry following the publication of Moradas de la voz. Notas sobre la poesía hispanoamericana contemporánea. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor of San Marcos, 2002. The following is a conversation with the poet from Piura.

* * *

MIGUEL ILDEFONSO: In your books the voice flows from the contemplation of the world.What were the most important moments of your life that influenced that voice in your poetry? I’m not referring to literary influences, but rather to events that have left their mark. What was the process in your development as a poet?

MIGUEL ÁNGEL ZAPATA: The dust and the sea were like a whirlwind when I was a child. My first six years were spent in a little town called Bellavista, in Piura. My father loved books and culture. My mother loved and still loves poetry. The silence of small towns resembles the silence in poetry. To be forced to be silent was the norm on nights of stormy winds. In the country, even the deaf can hear every noise, and the strange animals one sees, the insects and the river you cross for the first time, the papayas, the water wheels do not bear any resemblance to the mirages of the cities. My encounter with words came to me in my first contact with the sea, the countryside, and the salty river near my town. I always remember the dust of Bellavista, the wicket gate of my large house, the open sky and the bright afternoon sunlight. There is a force that opens your heart: it is the force of expressing the inexpressible, that waking dream which is poetry. Later, at the age of seven, when my family moved to Lima, I arrived with them and found the city big, but beautiful. Then, from the time I was a small child I could play with the memory of the pleasant objects and things of the countryside where I had lived before. I always wanted to describe my roan horse, which I learned to ride at a very young age, the gray-blue sky, the elves my sister Carmen talked about, and my cousins, who taught me other ways of being happy. I think that was the beginning of my first observations of the world and everything in it —even the smallest things are important.

M. I.: The first question was because I find in that voice a constant yearning for transcendence, a subdued voice which, at the same time, approaches a mystic state. In El cielo que me escribe (Ediciones El Tucán de Virginia, 2002) you have collected poems with this tone. What were the criteria for this collection?

M. Á. Z.: I collected them because my friend, the Mexican poet and editor, Victor Manuel Mendiola wanted to publish one of my books, and at that moment, I did not have many unpublished poems. So I sat down one night to put together poems that seemed to me to have the same contemplative attitude toward things and life. I wanted to show in some way a celebration of life, something that would say that life is beautiful, as well as pain and dreams. In the selective process I chose, perhaps unconsciously, poems which I liked because they marked a happy or sad stage of my life. I knew that poetry had been a transcendental escape during a difficult stage of my life during 1995 and 1996. At that time I had written my first poems that were in some way related to what is invisible, since I had already tried to speak with the great mute silence. On the other hand, I don’t believe that all the poems in El cielo que me escribe have a mystic slant. But that is up to the readers, each of whom has a different point of view, which should be respected because it is salutary. One does not choose the experiences, the events, they happen in your life whether you like it or not.

M. I.: It’s not for nothing that the act of writing is featured in the title, since it is a constant theme in your poems. Is it a ritual? Is it a path? I am quoting just a few phrases: “breeze from no tree where the poem is not written,” “With his beak he writes the loneliness of the night,” “I write at the window.” Is there a relationship?

M. Á. Z.: Writing is a ritual. The pleasure is so intense I can only compare it to sensual and sexual pleasure. The act of writing is in all the daily acts of our existence: the crow writes, the sky writes to you without meaning to, and the window, which is the threshold between happiness and pain, is also the space where the word enters and stays with you.

M. I.: In the poem “La ventana” I find an image that sums up that attitude I was talking about before: “I shall build a window in the middle of the street so as not to feel alone.” This is poetry, right? The poem talks about the construction of the poem, the poet, the poet’s home and, at the same time, the world. You have lived in the United States for many years. How have you maintained your relationship with Peru? On what street is that “window?”

M. Á. Z.: A beautiful commentary. The window is where the impossible happens. A window in the middle of the street is an escape to solitude and a joy, at the same time, since you build it yourself and you can write what you want, even though “the rain beats on the windowpanes,” and you have it there at your side to laugh and to write about what you would like to see in this world. I have seen many windows, and I believe that the window has been an indispensable object since ancient times. It is a look toward otherness, toward nowhere, toward the infinite to find another air and another sky. Emily Dickinson knew that other sky. Emerson and Rilke saw it in the sacred woods.

I have lived in the United States for many years, and my relationship with Peru gets stronger every day. Somehow, I kept Peru when I left Lima. I always return to see my mother, my brothers and sisters, my friends, to wander the streets and the nights of Lima, which for me is an unusual city, alive, fleeting, tremendously heartwarming and beautiful. Every city has its horrors and fascination, but not everything is horrifying or fascinating. For me, Lima is fascinating, which is why I return. That is why my window is on many streets, not just in Lima, also in Mexico City, in Buenos Aires, in New York.

M. I.: The presence of children (“I offer you these solitary roses which you planted when I placed on your forehead my alphabet of childish enthusiasm…”), of natural elements that write, such as the sky, give rise to the question: What are the aspirations of poetry and the poet?

M. Á. Z.: Arrogance with poetry leads to destruction. Innocence is stronger than wisdom, just as imagination is more important than knowledge, as Einstein would put it. It is an innocence imbued with a pure and uncontaminated world. That enthusiastic child was me when I was ten years old in Lima. To return to childhood is a wonderful thing. One should always be a child, and there are thousands of ways to be one. Poetry is precisely a way to dream that good times are coming and that the sky and bread will arrive at the window and at the table. That is why the aspiration of poetry is to enter the heart of the other, of the other that searches for something in order to see through the window, and feel a little faith in tomorrow’s horizon. The aspiration of poetry is for everything to speak: the animals, the trees, the rivers and lakes, and the sky that watches us every day, while we continue our little lives, running on the grass of time.

M. I.: Now for the typical question: which authors have influenced you? And with which contemporary poets do you feel affinity?

M. Á. Z.: We all have literary influences. What happens to me is that when I read a great poem, I immediately feel caught up by it and I write something that comes from only one word or one line. That is what happened to me once when I read a poem by Paul Celan that spoke of roses whispering. Isn’t that beautiful? The poem is titled “Crystal.” Sometimes it happens another way: I hear someone say something lovely, generally to women or children, and I steal those words and return them in the poem. Recently I was with my family in the house where Robert Louis Stevenson lived for seven months, recovering from tuberculosis in Saranac Lake in upstate New York. At that moment, just in front of the house, there was a large green field, surrounded by houses. Suddenly we saw some crows congregating there. My daughter said: “Papa, look at those crows camping on the lawn.” I immediately looked for a pencil to write the first part of a poem about those crows which had followed us to the Stevenson house. Poetry, as you can see, is everywhere, and the crows know what I am talking about.

Vallejo interests me, as well as Emerson, especially his poem, “Woods, A Prose Sonnet,” Theodore Roethke, all of Paul Celan and Kafka. There are many walls and windows in Kafka. Music is an important influence in my work, from the lyrics of rock, the tango, and Peruvian waltzes, to the music of Vivaldi, Elgar, Bach and Arcangelo Corelli. I play the Peruvian drum. And, as they say in Lima, I am a true native son (criollo), and I like partying. To be a real criollo is an art. Not just anyone can be criollo, and I mean it seriously. The music gives you something that words cannot give you: the direct force of a turbine that moves the heart and the senses. Something inexplicable happens when the musical staff vibrates. The cello is an instrument that touches my heart, and it is as if my heart speaks when I hear a suite for cello. Music is in the heart; it has the life force and is the language of the birds. Like Bach, one can be objective and passionate. Listening to Mozart’s Concertante Symphony for violin and viola has given me more than a hundred novels. I feel a kinship with contemporary poets who work with the relationship of spirit, nature and language. Those poets who care only about language are not my present or my future.

M. I.: You are also a literary critic. What do you think of contemporary Hispanic American poetry?

M. Á. Z.: Contemporary poetry continues with its transfigurations and ruptures, which in the end lead us to the same road: a return to the origin, that is to Homer, Horace, and later Dante. Hispanic American poetry will continue to be attractive and noteworthy as long as it does not distance itself from the classical cycle, and from the founding poets, not only of Hispano-America, but from the whole planet which gives us breath. We come from Darío, the poet of Azul… and Cantos de vida y esperanza. His body of poetry is still with us. We have to be open to the world, like Darío. On the other hand, there is a poetry I still do not understand, one that tries to play with language and nonsense without having carefully studied Góngora. There are certain poets who are writing impressionist poetry, exaggerated games that only lead to confusion and emptiness. They mistakenly look for the appearance of language, the surprise of the external, and they say absolutely nothing. In Trilce Vallejo was able to say what could not be put into words, but he said it well, as did Quevedo and San Juan. Some Hispanic American poets are able to do it well: Carlos Germán Belli, Jorge Eduardo Eielson, Alvaro Mutis, Ida Vitale, Eugenio Montejo, Oscar Hahn, Francisco Hernández, Raúl Zurita, and Victor Manuel Mendiola.

M. I.: What is the current state of North American poetry?

M. Á. Z.: North American poetry is going through one of its best periods. The best of the United States is found in its writers and artists, aside from its museums, libraries and large cities. Here in the New York area John Ashbery, Charles Simic, Billy Collins and Louise Gluck read their poetry. This country produced a rarity in world poetry of the twentieth century: Theodore Roethke. His work, with all of its cormorants and the serenity of its ponds and fishes, should be read carefully.

Right now I am finishing an anthology of selected contemporary North American poetry in Spanish translation. I am also finishing a book of my new versions of the poetry of Billy Collins. One of the leading lights of world poetry is here in the United States, and although most North Americans do not know it, he is even better, since poets who arrive here from elsewhere drink in his poetry as if it were a large goblet of red wine.

Con la publicación de El cielo que me escribe (México, 2002) Miguel Ángel Zapata se ha convertido en una presencia necesaria e innovadora en la nueva poesía hispanoamericana, y al mismo tiempo una autoridad en los estudios de la poesía hispanoamericana contemporánea con la publicación de Moradas de la voz. Notas sobre la poesía hispanoamericana contemporánea. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 2002. He aquí una conversación con el poeta piurano.

* * *

MIGUEL ILDEFONSO: En sus libros se va decantando una voz mediante la contemplación del mundo. ¿Cuáles han sido los momentos más importantes en su vida para que su poesía vaya adquiriendo esa voz? No me refiero a influencias literarias, sino a sucesos que lo han marcado. ¿Cómo ha sido su proceso de formación de poeta?

MIGUEL ÁNGEL ZAPATA: El polvo y el mar surgieron como un vendaval cuando era niño. Mis primeros seis años transcurrieron en un pueblito llamado Bellavista, en Piura. Mi padre era un hombre que amaba los libros y la cultura. Mi madre amaba y ama la poesía. El silencio de los pueblos pequeños se parece al silencio en la poesía. El estar callado a la fuerza era una pauta a seguir en la noche de los ventarrones. En el campo, cada ruido lo oye hasta el más sordo, y los animales raros que ves, los insectos y el río que cruzas por primera vez, los papayos, las norias, no se parecen en nada a los espejismos de las ciudades. Mi encuentro con la palabra se me dio en mi primer contacto con el mar, el campo, y el río salado que está cerca de mi pueblo. Siempre recuerdo el polvo de Bellavista, el postigo de mi casa grande, el cielo abierto y el sol fuerte de la tarde. Hay una fuerza que te abre el corazón: es la fuerza de expresar lo inexpresable, ese sueño real que es la poesía. Después, a los siete años, cuando mi familia se mudó a Lima, y con ellos yo llegué a una ciudad grande, pero hermosa para mí. Entonces, desde muy niño pude jugar con la memoria de los objetos, y las cosas agradables del campo donde antes había vivido. Siempre quise describir a mi caballo colorado, en el que comencé a aprender a montar desde muy pequeño. El cielo entre gris y azulino, los duendes de que hablaba mi hermana Carmen, y mis primas que me enseñaron a sentir la felicidad de otra manera. Así comenzó, me parece, mi primera contemplación del mundo, con todos sus objetos, hasta los más mínimos son importantes.

M. I.: La primera pregunta viene porque encuentro en esa voz una actitud en constante anhelo de trascendencia, una voz sosegada que, a su vez, se aproxima al estado místico. En El cielo que me escribe (Ediciones El Tucán de Virginia, 2002) ha reunido poemas con este tono. ¿Cuáles han sido los criterios de esta reunión?

M. Á. Z.: Los reuní porque mi amigo, el poeta y editor mexicano Víctor Manuel Mendiola, quería publicarme un libro, y en ese momento no tenía tantos poemas inéditos. Entonces me senté una noche a juntar poemas que tuvieran, según mi criterio, la misma actitud contemplativa sobre las cosas y la vida. Quería mostrar de alguna manera algo que celebrara la vida, que dijera que la vida es hermosa, y también el dolor, y los sueños. En el proceso selectivo, tal vez inconscientemente, seleccioné poemas que les tenía cariño porque marcaban una etapa feliz o dolorosa de mi vida. Sabía que la poesía había sido un escape trascendente para una etapa difícil durante 1995 y 1996. En esa época había escrito mis primeros poemas que tenían alguna relación con lo invisible, ya que había tratado de hablar con el gran silencio mudo. Por otro lado, no creo que todos los poemas de El cielo que me escribe tengan un corte místico. Pero eso es cosa de los lectores, cada uno tiene un criterio distinto, y eso hay que respetarlo porque es saludable. Uno no escoge las experiencias, los acontecimientos, sólo pasan por tu vida, quieras o no.

M. I.: No es por nada que el acto de escritura se señale en el título, puesto que es una constante en sus poemas. ¿Es un ritual? ¿Es una vía? Cito apenas unas frases: “brisa de ningún árbol donde no se escribe el poema”, “Escribe con su pico la soledad de la noche”, “Escribo en la ventana”. ¿Son las correspondencias?

M. Á. Z.: Escribir es un ritual. El gozo es tal que sólo lo puedo comparar con el gozo sensual y sexual. El acto de escribir está en todos los actos cotidianos de nuestra existencia: el cuervo escribe, el cielo te escribe sin querer, y la ventana, que es el limen entre la felicidad y el dolor, es también el espacio por donde pasa la palabra, y se va quedando contigo.

M. I.: En el poema “La ventana” encuentro una imagen que resume esa actitud de la que hablaba antes: “Voy a construir una ventana en medio de la calle para no sentirme solo”. Esto es la poesía, ¿cierto? El poema habla de la construcción del poema, del poeta, del hogar del poeta y, a su vez, del mundo. Usted vive hace muchos años en Estados Unidos, ¿Cómo ha mantenido su relación con Perú? ¿Aquella “ventana” en qué calle está?

M. Á. Z.: Hermoso comentario. La ventana es el lugar donde sucede lo imposible. Una ventana en medio de la calle es un escape hacia la soledad, y una alegría, al mismo tiempo, ya que tú la construyes y puedes escribir lo que gustes aunque “la lluvia golpee los cristales”, y la tienes ahí a tu lado para reír y escribir sobre lo que quisieras ver en este mundo. He visto muchas ventanas, y creo que la ventana es un objeto indispensable desde la antigüedad de los tiempos. Es un mirar hacia la otredad, hacia el no lugar, hacia el infinito para encontrar otro aire y otro cielo. Emily Dickinson conoció ese otro cielo. Emerson y Rilke lo vieron en los bosques sagrados.

Hace muchos años que vivo en Estados Unidos, y mi relación con el Perú es cada día más fuerte. De alguna manera, me quedé con el Perú cuando salí de Lima. Siempre vuelvo a ver a mi madre, a mis hermanos, a mis amigos, a recorrer las calles y las noches de Lima, que para mí es una ciudad inusual, viva, fugaz, tremendamente entrañable y hermosa. Cada ciudad tiene su horror y fascinación pero no todo es horroroso ni fascinante. Para mí Lima es fascinante, por eso vuelvo. Por eso mi ventana está en muchas calles, no sólo en Lima, también en la ciudad de México, en Buenos Aires, en Nueva York.

M. I.: La presencia de niños (“te ofrezco estas rosas anacoretas que tú sembraste cuando dejé en tu frente mi abecedario de niño entusiasmado…”), de seres de la naturaleza que escriben, así como el cielo, me incita a preguntar ¿cuál es el anhelo de la poesía, por ende del poeta?

M. Á. Z.: El ser demasiado arrogante con la poesía te lleva a la destrucción. La inocencia es más fuerte que la sabiduría, así como la imaginación es más importante que el conocimiento, como quería Einstein. Es una inocencia que tiene que ver con la absorción de un mundo puro y contaminado. Ese niño entusiasmado era yo cuando tenía diez años en Lima. Volver a la niñez es algo maravilloso, siempre hay que ser niño. Hay miles de maneras de serlo. La poesía es justamente una manera de soñar que el buen tiempo vendrá, y que el cielo y el pan llegarán a la ventana y a la mesa. Por eso el anhelo de la poesía es llegar a penetrar el corazón del otro, de la otra que busca algo para ver al otro lado de la ventana, y sentir un poco de fe en el horizonte de mañana. El anhelo de la poesía es hacer que todos hablen: los animales, los árboles, los ríos como lagos, y el cielo que nos mira todos los días mientras seguimos con nuestras viditas saltando sobre la grama del tiempo.

M. I.: Ahora sí viene la pregunta típica, ¿cuáles han sido los autores que lo han influido? ¿Y con qué poetas de la actualidad encuentra afinidades?

M. Á. Z.: Todos tenemos influencias en la literatura. A mí me pasa que cuando leo un gran poema de inmediato me siento contagiado y escribo algo que deviene sólo de alguna palabra o de una oración. Así me sucedió una vez que leí un poema de Paul Celan que hablaba de las rosas susurrando, ¿no es eso hermoso? El poema se llama “Cristal”. A veces pasa de otra forma: escucho a alguien decir algo lindo, por lo general a mujeres o a niños, y me robo esas palabras y las devuelvo en el poema. Hace poco estuve con mi familia en la casa de Robert Louis Stevenson, donde vivió durante siete meses tratando de curarse de la tuberculosis que padecía, en Saranac Lake, al norte del estado de Nueva York. En ese momento, justo al frente de la casa, había un campo verde enorme rodeado de casas, de repente vimos unos cuervos merodeando por ahí. Mi hija dijo: “Papi, mira esos cuervos acampando en la pradera”. De inmediato busqué un lapicero para escribir la primera parte de un poema sobre estos cuervos que habían venido siguiéndonos hasta la casa de Stevenson. La poesía, como se puede ver, está en todas partes, y los cuervos saben de lo que hablo.

Me interesa Vallejo, también Emerson, sobre todo su poema “Bosques, un soneto en prosa”, Theodore Roethke, todo Paul Celan y Kafka. Hay muchos muros y ventanas en Kafka. Una influencia importante en mi trabajo es la música, desde la lírica del rock, el tango, los valses criollos peruanos, hasta las canciones de Vivaldi, Elgar, Bach, y Arcangelo Corelli. Yo toco el cajón peruano, como se dice en Lima, soy “criollo” y me gusta la jarana. El ser criollo de verdad es un arte. Cualquiera no puede ser “criollo”, lo digo en serio. La música te da algo que las palabras no pueden darte: la fuerza directa de la turbina que mueve el corazón y los sentidos. Algo inexplicable pasa cuando vibra el pentagrama. El chelo es un instrumento que me llega al corazón, y pareciera que mi corazón habla cuando oigo una suite para chelo. La música está en el corazón, tiene la fuerza de la vida y es el lenguaje de los pájaros. Igual que Bach se puede ser objetivo y apasionado. Escuchar la Sinfonía concertante para violín y viola de Mozart me ha dado más que cien novelas. Me siento afín con los poetas actuales que trabajan la relación con el espíritu, la naturaleza y el lenguaje. Aquéllos poetas que sólo se preocupan por el lenguaje no son ni mi presente ni mi futuro.

M. I.: Usted también es crítico literario. ¿Cómo ve la poesía hispanoamericana actual?

M. Á. Z.: La poesía actual sigue con sus transfiguraciones y rupturas, que al final nos conducen al mismo camino: la vuelta al origen, es decir a Homero, Horacio y después Dante. La poesía hispanoamericana seguirá siendo atractiva y novedosa mientras no se aleje del ciclo clásico, y de los poetas fundadores no sólo de Hispanoamérica sino de todo el planeta que nos respira. Venimos de Darío, el poeta de Azul… y Cantos de vida y esperanza. Su obra poética aún está presente entre nosotros. Hay que estar abierto al mundo como Darío. Por otro lado, hay una poesía que aún no termino de entender, aquella que trata de jugar con el lenguaje y el sinsentido sin haber leído bien a Góngora. Hay ciertos poetas que están escribiendo poemas impresionistas, juegos exagerados que sólo llevan a la confusión y al vacío. Ellos, engañados, buscan una apariencia en el lenguaje, lo sorprendente de lo externo, y no dicen absolutamente nada. Vallejo logró en Trilce decir lo indecible, pero lo dijo bien, lo mismo Quevedo, y San Juan. Algunos poetas hispanoamericanos lo logran y lo hacen bien: Carlos Germán Belli, Jorge Eduardo Eielson, Alvaro Mutis, Ida Vitale, Eugenio Montejo, Óscar Hahn, Francisco Hernández, Raúl Zurita, y Víctor Manuel Mendiola.

M. I.: ¿Cómo está la poesía norteamericana en la actualidad?

M. Á. Z.: La poesía norteamericana pasa por uno de sus mejores momentos. Lo mejor de Estados Unidos son sus escritores y sus artistas, aparte de sus museos, bibliotecas y grandes ciudades. Aquí por Nueva York leen sus poemas John Ashbery, Charles Simic, Billy Collins y Louise Glück. Este país produjo un raro en la poesía mundial del siglo XX: Theodore Roethke. A él hay que leerlo bien con todos sus cormoranes y la serenidad de sus estanques y sus peces.

Ahora mismo estoy terminando una antología selecta de la poesía norteamericana contemporánea traducida al español. También termino un libro con mis nuevas versiones al español de la poesía de Billy Collins. Uno de los faros más importantes de la poesía en el mundo está aquí en Estados Unidos, y aunque la mayoría de los norteamericanos no lo sepan, mejor aún, ya que los poetas que llegamos de afuera nos bebemos todo como una gran copa de vino tinto.