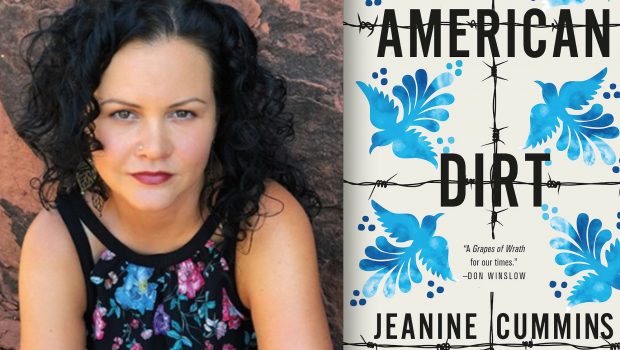

Thoughts on American Dirt, by Jeanine Cummins

Mariana Villegas Triay

At the time of this writing, it’s been three days since the release of American Dirt, dubbed in my Advance Review Copy “the most anticipated book of 2020”. I will not attempt to review the book’s literary merits for several reasons, chief among them the fact that it has already been done by writers and readers more qualified than me and, in the spirit of full disclosure, the fact that I didn’t finish it. What I will attempt to do instead is to analyze the public conversation that ensued in the wake of its official publication.

I have been following the controversy over the book on Twitter for the past three days, and I have to admit that I am very happy this conversation is taking place. We owe much of it to Myriam Gurba, whose review of the book entitled “Pendeja, You Ain’t Steinbeck: My Bronca with Fake-Ass Social Justice Literature” was published just over a month ago in Tropics of Meta (after receiving a kill fee from another publication because she “lacked the fame to pen something so negative”), and who has kept the conversation going ever since. I read her review around the time it came out, and as good as I think her review was, I am ashamed to admit that I didn’t think it would take much hold in the mainstream conversation around this book.

I’m happy to report that I was very wrong. Not only has Gurba’s persistence on Twitter managed to grab the attention of a diversity of individual writers and literary personalities, but she’s also managed to position the conversation on mainstream media: her review was quoted in Lauren Groff’s own review of American Dirt for The New York Times (even though this review caused its own controversy and didn’t make Gurba too happy) and has since been quoted in almost every piece written about the book and the conversation surrounding it. The controversy has been so strong and the pushback from its publishers so aggressive, that it has been criticism of the book that has actually and effectively “built a bridge” across the border. Today, David Miklos, a writer based in Mexico City, asked on his Twitter “Why is it that when there’s a book on Trump or a pamphlet by AMLO the PDF version takes no time at all to arrive on my inbox or Whatsapp in altruistic fashion? Is there anyone kind enough to send me a copy of @jeaninecummins American Dirt so I can turn it into dust?” (my own translation from the Spanish).

As with most conversations occurring mainly on Twitter and other social media (in this case, #Bookstagram in particular), this one is being portrayed as a discussion between members of two very distinct and even opposite camps. One is supposedly composed of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans, backed by those referred to as POCs in the US; while the other is supposedly integrated mainly by white Americans. I have my own issues with this binary distinction for many different reasons, one of them being that it was actually used as a tool to silence me from having an opinion on all this. I was told, by an acquaintance whose identity I’m choosing to withhold, that I am too “white” to get involved in this discussion. It’s funny as at other times I haven’t been white enough in the U.S. (Mind you, none of those times has my ambiguous identity been a choice; it’s always been imposed on me by someone else—and not necessarily white Americans. The obsession with the contingencies of my birth and my looks and the openly expressed shock at someone who can speak English well despite it being their second language will never stop amusing me, but that’s a whole different story.)

My right to have an opinion on this book does not rest on the fact that I’m más mexicana que el nopal. It rests on the fact that I might have an interesting perspective to add to the conversation. And this is exactly the point I believe is being diluted with all the screaming happening on Twitter. The problem with this book is not the identity of its writer. The main point of contention with Cummins’ book is about its execution (which Parul Sehgal’s review for The New York Times brilliantly describes, adding to Gurba’s own take) and the power structures behind its publication and promotion. But it also has to do with the counterproductive effect this book is having even against Cummins’ own goals for it.

In the “Author’s Note”, Cummins justifies the writing of the book by arguing that she could form a bridge of understanding:

“I worried that, as a nonmigrant and non-Mexican, I had no business writing a book set almost entirely in Mexico, set entirely among migrants. I wish someone slightly browner than me would write it. But then, I thought, If you’re a person who has the capacity to be a bridge, why not be a bridge? So I began.”

As Norma Iglesias-Prieto of the Chicano Studies Department at San Diego State University reportedly told her, we do need as many voices as we can get telling this story. I have been working with immigrants and refugees in some capacity or another for most of my professional career. The last four years I have been living and working in the border with Mexican immigrants in my capacity as diplomatic officer —first in Nogales, and now in San Diego. I still have much to learn about immigration and the dynamics behind it. I honestly don’t think I will ever fully understand the phenomenon. But if there is one thing I have learned while living in the borderlands, it is that even though there are many US citizens working hard for the benefit of immigrants and refugees, their stories and voices still need to reach the mainstream. What I mean to say is, we already have many allies telling our shared stories truthfully so, if a voice as loud as Cummins’ is going to join the conversation, everyone already engaging in it will expect it to be at least as truthful as their own.

In her own explanations for the book in both her own “Author’s Note” and a letter from the publisher which appears on my ARC (in Mexico we have a saying that goes a explicación no pedida, culpabilidad manifiesta, which loosely translates as “if you have to explain yourself even before anyone requests that you do so, it probably means you are guilty as charged”), Cummins seems to agonize about her right to write this book. The mistake she makes is similar to what some of the critics of her book have been making: she is blaming that guilty feeling on her identity.

At the risk of repeating myself, this is not (should not be) about identity. There are so many voices across the very thoroughly-categorized American spectrum of identity helping to build bridges between Mexico and the U.S. This was the case before the 2016 US election and has become even more evident in the years since. These voices include many white American allies working for the benefit of immigrants and refugees. Some of them are even affecting structural and institutional change. Staff and volunteers of the Kino Border Initiative, No More Deaths, Border Angels, local chapters of ACLU (and in some cases ACLU national), Anti-Defamation League and countless other individuals and organizations, José Antonio Elena Rodríguez, Sergio Adrián Hernández Güereca, Pedro, Juan, María, Luis Carlos, Brayan, César, and hundreds of others immigrants and refugees, have very distinct faces, even unforgettable ones. All of these allies are very well aware of the situation and know that none of these individuals belong to a “faceless brown mass”. The allies are many and they own their voices. We just need to pay more attention.

Cummins’s loud voice has failed to do what it attempted. Regardless of her intentions, American Dirt is only helping to perpetuate stereotypes about both Mexicans and Americans. It does a great disservice to the people on both sides of the border actually working to build bridges. It undermines the conversations and cultural dialogue which happen on a daily basis between our societies.

My thoughts are strictly personal and in no way represent an official position from the government I work for. However, they are of course informed by the experiences I’ve had in my position and the lessons I’ve learned throughout my professional career. I cannot help but think of two specific lenses through which the American Dirt controversy should be seen and analyzed from a foreign policy standpoint.

On the one hand, it is a conversation that deeply affects the Mexican and Mexican-American community, especially those involved in the literary world. As much support as Gurba has garnered against the novel, there are also some Mexican-American writers who have expressed enthusiastic praise for the novel, with Sandra Cisneros hailing it as “the great novel of las Americas”. As I have already mentioned above, the novel hasn’t been published in Mexico, and while the controversy surrounding it has sparked curiosity South of the border, I am almost certain that the whole affair will take on a whole new dimension as soon as it can be read and reviewed by Mexicans living in Mexico, highlighting once more the differences in cultural consumption and biases among Mexicans living in different societies. This will be interesting to watch.

On the other hand, this book has the potential to deeply affect Mexico’s image abroad. This morning I was listening to Damian Barr’s Literary Salon in the UK, whose interviews I normally enjoy very much due to their insight. He begins the session by saying that Mexico again is featured in some newspaper headline due to more gang violence on its streets, and that even though he’s seen that a lot, this time the news “felt different,” “felt personal,” as he found himself “looking at the people involved in it and looking for individuals among the numbers, stories behind the headlines”, all because of Cummins’s book. I don’t disagree that some headlines can seem so remote to our own realities that we need stories in order to humanize those going through them. That is the power of story. But the story that Cummins’s is portraying in her book is contending with what should be a familiar reality to most Americans. It’s happening in their backyard. The issue is that the story seems so alien to so many Americans, even when it’s been part of their reality for decades. And it doesn’t help that a lot of people are reacting as though this were the first time this story is being told, when in fact an enormous array of Mexican and Mexican-American writers are telling their stories.

In the interview with Barr, additionally, when asked about her knowledge of how cartels operate, Cummins goes on to say that she wanted to stay alive and didn’t actually do the research that many Mexican writers and journalists have actually lost their lives or live in exile for pursuing. She just read “everything” she could get her hands on, citing Netflix shows and documentaries as a source for her fiction. Many writers who have actually researched this topic will tell us how problematic this is. But this novel goes into the same problematic stance of elevating “narco-culture” (narcocultura) through literature. The reach is global, as demonstrated by Cummins’s interview with Barr.

Something I really admire about Gurba’s criticism of this book is that she has been constructive by proposing reading lists with books and authors actually doing a great job of telling their own voice stories and building bridges. Besides backing Gurba’s suggestions on Chicano writers to explore, I would like to add a further suggestion. Read more literature in translation. Read writers who are still living in their countries and writing in their languages and telling us their stories. There are so many Mexican contemporary writers who have been beautifully translated by several brilliant young translators. At the risk of providing a biased and incomplete list, I suggest trying Jorge Comensal translated by Charlotte Whittle, Laia Jufresa and Fernanda Melchor translated by Sophie Hughes, Juan Pablo Villalobos translated by Rosalind Harvey. Find the translations for Guadalupe Nettel, Antonio Ortuño, Franco Félix, Daniel Saldaña París, Emiliano Monge, David Miklos. Even better: become bilingual and read them in the original Spanish. Read outsiders, like Courtney Maum and Alejandro Zambra and Roberto Bolaño, who write about Mexico with authority and care. Because the problem is not that an American writer chose to tell a story about Mexico, the problem is that she did not succeed in reconciling the discomfort of her privilege and failed to identify her biases.

Mariana Villegas Triay is a Mexican Foreign Service officer based in San Diego, California. She was posted in Nogales, Arizona for two-and-a-half years, where she worked closely with Mexican immigrants and refugees. She currently manages the Program for Mexicans Abroad, which includes mainly education and health initiatives, at the Consulate General of Mexico in San Diego. She’s an avid reader and an aspiring translator. Her Twitter is @vtriay

Mariana Villegas Triay is a Mexican Foreign Service officer based in San Diego, California. She was posted in Nogales, Arizona for two-and-a-half years, where she worked closely with Mexican immigrants and refugees. She currently manages the Program for Mexicans Abroad, which includes mainly education and health initiatives, at the Consulate General of Mexico in San Diego. She’s an avid reader and an aspiring translator. Her Twitter is @vtriay

©Literal Publishing

Posted: January 24, 2020 at 9:36 pm