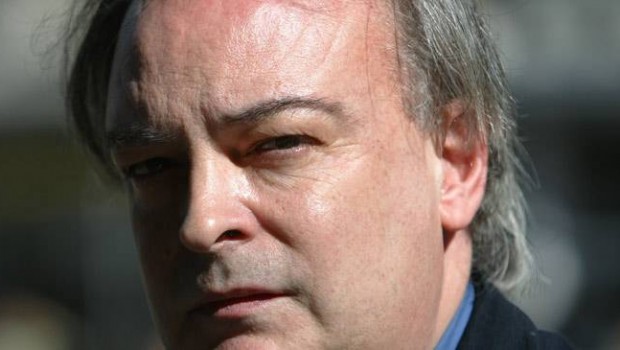

Valley Confidential: Rolando Hinojosa

Mónica María Parle

You won’t find Belken County, Texas in a world atlas or even a Texas road atlas. Don’t contact AAA for directions, and don’t bother trying to find a key map of its flagship town, Klail City. This province exists in a fictional space, but its spirit lies very much in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley and in the mind of fans and its creator, Rolando Hinojosa.

Hinojosa spent his youth in Mercedes, Texas, a small town in the Valley, where he saw the ins-and-outs of a town enriched by its geographical location along the US/Mexico Border. That bilingual, bicultural world springs into vivid, bustling color on the pages of his numerous novels set in the fictional town of Klail City. Beginning with the first novel in the series, Estampas del valle, Hinojosa is unafraid to tackle the conflicts his inhabitants face in harrowing world-scale situations, like The Useless Servants, where he charts one character’s experiences in the Korean War. Nor does he ignore the more private, homefront battles, as in the case of Becky and Her Friends, or instances in which the community confronts local violence, as in his mystery novels featuring Rafe Buenrostro, Partners in Crime and Ask a Policeman. But even these distinctions are too easy; his novels brim with the sense that each community member is a player on a larger stage, and they return each time more complex in novel after novel, scene after scene. Throughout, Hinojosa’s fiction allows the reader to be exposed to myriad voices and situations by bridging a wide-range of forms: from epistolary to dialogue to collage.

His latest, We Happy Few, revisits Belken’s fertile fictional landscape, this time depicting a university in the midst of change as its much-respected president battles a terminal illness. As in his previous efforts, Hinojosa isn’t content to force the reader to stand outside the windows watching his characters from afar; instead, he brings us into classrooms, offices, and board meetings, allowing us access to the public—and often private—conversations and the constant swirling rumors that beset the university.

This atmosphere is familiar to Hinojosa, who has spent a significant portion of his life in academia. Born into a family of teachers, Hinojosa has taught for many years at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is the Ellen Clayton Garwood Professor of Creative Writing. He is also the author of a collection of poetry about his experiences in the Korean War, Korean Love Songs. Hinojosa has won numerous awards for his work, including the coveted 1976 Casa de las Américas prize. American literature has been indelibly influenced by his work.

Recently, I had the opportunity to exchange some emails with Hinojosa about his fiction and his influences.

* * *

Mónica María Parle: You’re careful to note in We Happy Few that all the characters, the town, and even the university are fictional. Do you get asked to comment on the reality of the series?

Rolando Hinojosa: Yes, I’m often asked to comment on the reality of the characters. Readers, students and non-students alike, tell me that what they read in the Series is something they knew, read, saw, or heard of, and so on, usually in their hometown. This has been going on since ‘72 when Por esas cosas que pasan appeared in a number of El grito. A student in Kingsville said the killing had happened in San Juan. I said I was writing about a killing in Mercedes and that I changed some things; the weapon for one, the motive for another, as well as the time, and the place. I explained that was the way writers work, one uses an action and brings it to life through dramatization; the old Henry James advice. When readers usually identify with a character or with an event, they set about in making connections with real characters and real places. It’s neither uncommon nor infrequent when they do so.

M. P.: The New York Times compared you to several of the greats of American and world literature, specifically mentioning Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha and Marquez’s Macondo. Did you have either of these authors in mind when creating Klail City or Belken County?

R. H.: I don’t think the quote in the Times compared me to either Faulkner or Márquez; it was more of a comparison of the use of a place to set the writing. It would be beyond flattery to have me compared to Faulkner or to anyone of that stature. The earliest influence regarding a series came from reading Benito Pérez Galdós, Novelas españolas contemporáneas; years later, I read Anthony Powell’s series A Dance to the Music of Time and I’d read some Proust off and on until I got serious and began reading his work systematically. But as far as influence, almost any writer whose work I’ve read over and over has influenced me and given me the idea of a series. Heinrich Böll did not write a series but the focus was on World War II and the years that followed and this too constituted continuity in characterization if not in characters.

M. P.: I read an interview you did in 2000 (in the Bilingual Review) where you talk about reading the World War I poets Sassoon as you were trying to write Korean Love Songs. Were there any fiction writers that particularly influenced the Klail City series?

R. H.: The origin for Korean Love Songs came from reading Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory. He wrote of the wartime experiences of young British soldiers, mostly public school boys such as Siegfried Sassoon, and Robert Graves, and others. I didn’t think that a linear novel about the Korean War would be the way to write about the war, and I decided to write it in narrative verse. It worked; by the way, a writer doesn’t know what will happen after publication, and K.L.S. is an example; it was published by Justa Publications in l978 and followed with a second printing in l980. Each run turned out 500 copies. I published parts of it here and there and it wasn’t until thirteen years later that the bilingual German-English version was published by Osnabrück University under the dual title, Korean Love Songs/Korea Liebes Lieder; the translation, and it’s a fine one, was done by Wolfgang Karrer. That was it, I thought, but then some ten years after that, the United States Air Force Academy published it in total. Parts of it began appearing here and there once again and then the chairman of the English Department at the United States Military Academy requested permission to use some of the pieces in his class. As I said, one never knows what will happen to one’s writing after publication.

I’ve mentioned two of the writers who influenced the writing of K.L.S., but there was also Isaac Rosenberg, Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen, and others such as Edmund Blunden. I didn’t read or study them to teach a course on World War I poetry. I wanted to see what it was they did, how they did it, and since I’m not a poet, narrative verse was the way to go.

American contribution to World War I prose fiction or poetry can be regarded as nil unless one brings up the poet Joyce Kilmer but, to paraphrase Alexander Pope, “Who now reads Kilmer?” In passing, no Mexican American literary critic knows what I did regarding meter; I used Spanish syllables although I wrote in English. I used the six and eight syllable verses, the popular eight and ten syllables as well as hepta- and endecasyllables, the learned seven and eleven syllables introduced during Spain’s Golden Age by Juan Boscán, the Catalan writer.

M. P.: One thing that I’m drawn to in your work is that it occupies a very real, if fictional, space. This is a community: characters overlap from novel to novel and the family, romantic, and professional relationships tie all of the characters together. When you started out, did you envision this intricate web of works? Or does each new book evolve from a past book?

R. H.: When I started out, I didn’t want to write a linear, nineteenth century novel. I wanted to present a people as the protagonist using various narrators and points of view. The idea of a place or places came from the Valley’s geography where towns are separated on an average of six miles; some are closer, others farther apart, but six is the average. This is no coincidence; the farmers reached an agreement with the railroad builders that would help them bring their produce quicker to the railroad lines. Coming from an old family, that is, the settlers who came up from various towns and cities in Mexico in the mid eighteenth century, the blood and kin relationships became part of one’s life. Also, as a high school youngster, I would hitchhike all over the Valley; it was safe then, or perhaps, safer and certainly much safer than it is now.

As for intricacy, and one should include intimacy and familiarly with the place, this arose from the writing itself. I use, with one exception, old Valley names: Salinas, García, Garza, Treviño, and so on. Some readers, unfamiliar with Valley names are surprised with the use of Buenrostro and Malacara as last names; a cursory look of the Valley telephone directory will reveal those last names on both sides of the Rio Grande. Buenrostro, again by the by, doesn’t mean Goodface; it means Fairchild. The Valley includes both sides of the river, and, as you may know, I use both sides. Knowing the written and the oral histories of the place, as a child, listening to stories and events of the Mexican Revolution of 1910, and the coming of the Anglos in the Twenties and life itself helped, as all relationships are a help to writers. The Valley is not a valley, it’s a delta, but it was so called by those who enticed the Anglo settlers to the area during the first and second decades of the twentieth century.

The evolution of the Series came piece by piece; I had envisioned a picaresque novel but stopped in the middle of Klail City y sus alrededores and went on to write what I’ve produced since then. The use of humor is inescapable, after all, life contains ups and downs and the comic as well as other parts of humor: wit, satire, sarcasm, cynicism, and the sardonic, too, since each presents one all manner of writing opportunities.

M. P.: Another “real” aspect that is continually present in your work is the concerns of class, ethics, ethnicity, and racism. All of your books seem so conscious of this, however, the meat of We Happy Few is based on these tensions. Do you think that the university setting draws this out? That these discussions are just beneath the skin in the university climate?

R. H.: Class is important, as well as color; this is universal, it isn’t a property of this country. And you’re right in that ethics figure and play an important in the Series. As for ethnicity and racism, to eschew or to pretend that racism doesn’t exist all over the world is naive; ethnicity in a multiethnic society such as ours is likewise part of our daily living as much as is accommodation, resistance, betrayal, and loyalty, themes which are presented in prose fiction because all play a part in daily living. Their inclusion is no accident; to exclude them would constitute deliberate blindness to reality or to take a political side that wishes to erase past and present history. That’s not me nor is it my experience. Faulkner, in his Nobel speech said, among other important matters, that the writer cannot afford to be fearful; I’ve quoted him before on this, and it bears repeating.

When someone says all writing is political, some people blanch; well, writing is political. Some write that everything is right with the world and may be paid to write in that vein, but what they write isn’t the truth. It resembles some prescriptive device that seeks to present only an optimistic point of view instead of a realistic one. A realistic view presents optimism as well, but it also seeks to present reality by way of contrast in a search, and this may sound self-important, in a search for truth. Of course, it’s fiction, but not the type of fiction that presents one and only one point of view.

As for We Happy Few, there’s racism among some professors but the majority is not racist; that’s the same in this country where millions of our fellow citizens are racists, but they are outnumbered by more millions who are not, otherwise life would be unbearable for all, including the racists. If everyone is a racist, then who is there to hate? All universities are formed by conservatives and liberals and middle-of-the-roaders; there’s nothing new there since they play the same role away from the academy. The larger section, The Faculty, shows much gossip, unfounded rumors, good-natured ribbing, recognition of talent among colleagues, and dedicated professors as well as time-servers. In brief, the world in an academic setting.

To me, the University climate is no different from the rest of the world. It is populated by a more educated class, and that’s a difference, but you’ll find few academics who are wealthy; most worked their way to earn their undergraduate and senior graduate degrees. That this gives them, or me, a more tolerant point of view may be due not only to the high degree of education since one’s family, acquaintances, and close friends also play an important part in the makeup of those of us who profess.

What may make W H F different is not its setting; Mary McCarthy’s Groves of Academe, Randall Jarrell’s Pictures from an Institution, the David Lodge novels, or earlier ones, say, Stringfellow Bahr’s Strictly Academic do not touch on high administration to any degree or to the members of the board of directors; they may make mention of them and the appearance of students is casual; not in W H F where everyone plays a part and shows the changes in higher education. Added to which, mine is a shorter novel. I haven’t read a campus or an academic novel in years, but the mind retains them and mine adds one more genre of prose fiction to the Series.

M. P.: Each of the novels reflects a bilingual consciousness; characters function between two languages and cultures. Even their manner of speaking English is influenced by Spanish in terms of pacing, syntax, and word choice. In that 1999 interview you talk about switching between Spanish and English when you got stuck in both Korean Love Songs and Useless Servants. When you sit down to work on a project, do you make a conscious decision about what language you’ll use?

R. H.: It is only natural common sense to reflect a bilingual and bicultural consciousness in the Series; Faulkner and Flannary O’Connor are conscious, of their culture as is Henry Roth when he presents us with his Jewish characters as does Philip Roth later on. One writes about what one knows is an old piece of advice. What’s important is to know what you know. I’m not conscious in terms of syntax or word choice although I am regarding pacing; without it, novels get out of whack. That I balance a bilingual consciousness is inescapable. I lived the first seventeen years of my life in the Valley; I returned to it after college and then left it again to pursue graduate work after some nine years of working down there. But it was those seventeen years that did it. Some dispute the primacy of the early years and they’re welcome to their opinion since what they express is an opinion, not a universal fact. My life down there, its history, its political, and the society’s hierarchical structures formed part of my thinking; my leaving it, my subsequent education, and meeting all manner of people also helped. I didn’t recognize it at the time, but I was ahead of the game since I come from a family of readers and teachers.

Regarding being stuck when you mention Korean Love Songs, that occurred when a Mexican friend heard part of the work in English and suggested I translate it into Spanish. I gave it a try, but it didn’t work. My military life was not lived in Spanish and the same would go for Servants although I had and have no intention of doing a translation. I could rewrite it as a linear novel and it would be a different because of the form and structure I would have to use.

I don’t believe I make a conscious decision regarding which language to use. To do so would perhaps, perhaps, force me to work from an outline or a detailed form. I can’t do this. The writing may come from a phrase in one language or the other, an overheard word may trigger a piece of writing, but writing a novel is something else. Or it is with me, at any rate. I remember reading George Meredith’s The Egoist and by the time I read the scholar’s introduction and a third of the book, I stopped; not out of boredom, you understand, but because Becky Escobar appeared and Los amigos de Becky was the result. From an airhead in Mi querido Rafa/Dear Rafe to a self-actualized person, to use that current term, was a lucky stroke for me. She was another person now; independent, mature, tired of her dull life and living for others and not for herself or for her children. She must have known for a long time that Ira her husband was a nothing, and she decided—and decisions of any kind are difficult for most people—she made the most important decision in her life. She realized she had some thirty-five more years on earth, and she was not going to spend them with him.

It came to me in Spanish and worked some seven months on it when I hit a wall; I couldn’t go on. I rested up and started an English version and wrote much of it one summer in Iraq where I was setting up an American literature curriculum at Mosul University. Finished it, sent it to Nick Kanellos and he accepted it. After some months, I picked up the Spanish version and I told Nick of my plans to start it again. He said he’d look at it when I finished it.

How does one explain how writing works? How I chose one language, switched, and then returned to the original version? It’s not confusing to me, but it is a mystery. And, both versions are a long way from Meredith’s Egoist; it just happened that as I was reading it, Becky appeared from somewhere.

From your reading, you know that I did something new again; no narrator, no main character other than Becky who speaks in one version but not in the other, and the decision that multiple narrators, in first person, would carry the book.

Posted: April 6, 2012 at 7:53 pm