Andrea Chapela: “I always need to be in a state of doubt.”

Alba Lara Granero

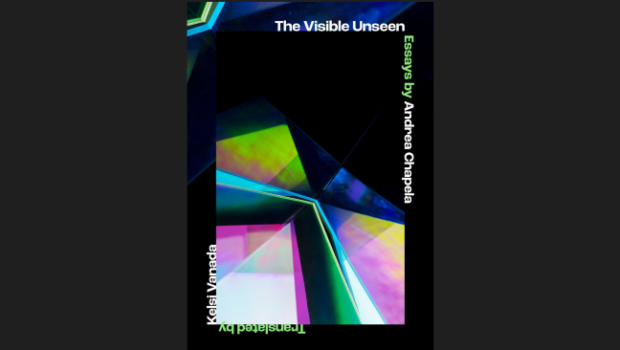

We talked to Mexican author Andrea Chapela about her upcoming debut in English, The Visible Unseen (Restless Books, 2022).

In a world where science and the humanities seem to have little do with one another, the work of Mexican writer Andrea Chapela suggests otherwise. Chapela, one of the most interesting emerging Spanish-language writers, according to Granta, is also a chemist. She comes from a family of scientists: her mom is a mathematician, her dad, a physicist, her sister, a biologist. Her literary production, astoundingly prolific and successful for a writer at just 30, includes eight books and dozens of short-stories. The Visible Unseen, an award-winning collection of essays about seeing, science, life, and writing, marks her literary debut in English.

Alba Lara Granero: Let’s start with the title of your forthcoming book, what is visible but unseen?

Andrea Chapela: My first thought was feelings, but then again, there are so many things around us that are “visible” but unseen. On the one hand, the book is about emotions, and how slippery they can be. They are visible, but, in many ways, they’re beyond language–therefore unseen. On the other hand, scientific ideas that are too big or too small for our senses exist. We can perceive them, but we can’t see them. We can’t only trust our eyes for objects perceptible to human sight. The Visible Unseen isn’t a direct translation from the Spanish, but I feel it encompasses the ideas of the book beautifully.

ALG: That’s true. The original title in Spanish is Grados de miopía (“degrees of myopia”). You wrote it in Spanish… and the book reflects on language a lot. How does it feel to read it now in a different language?

AC: I’m very lucky because the person who translated the book is a very good friend of mine, Kelsi Vanada. She watched me write this book, and we talked about it a lot. Kelsi has also been translating me for a long time, to the extent that I think she understands my writing process better than me. It’s a big delight to read the book in English now, and to see, not only how she deals with having to translate from one language to another, but also how she tried to understand the science in the book so deeply that she could see it. She told me she learned a lot about entropy and experiments. She did a great job. Kelsi is also a great poet. I think she sometimes makes me sound better than I do normally.

ALG: Every essay has one “object of study”: glass, mirrors, light. Why did you choose those three? Did you think of any other possible “object of study”?

AC: I wanted to include another object of study: the eyes. I always thought that I would write an essay about the act of someone seeing me… I planned it, and I even sketched a bit. But at the time I was writing this book, that topic felt very heavy to me. It made me very emotional… But trying to find how to write that piece, I came across the history of light and became fascinated by that. So I wrote that essay instead and made it the third and final one of the book. Only recently have I been thinking of going back and writing that piece on the eyes, but it’s only an idea for now.

Every essay of The Visible Unseen expands on those “objects of study” freely. Family stories, scientific facts, and observations about the world and language interweave into what results in a very personal and poetic narrative. The book is an attempt to come to terms with the dual identity of her scientific background and her literary present.

ALG: Did you get to terms with that “dual identity”?

AC: Yes. At least I understood that my “scientific identity” was a fertile ground for writing, and that choosing “art” didn’t mean I had to stop understanding or being curious about the world in other ways. I understood that the only thing I have to give, truly, while writing, is my point of view, and that my experience and love of science makes this point of view unique. In some ways, it has given me the freedom and courage to keep expanding my “identity.”

ALG: And speaking of identity, your book focuses a lot on your relationship with your parents and your upbringing. I got the impression that The Visible Unseen is also a book about childhood, but with the interesting difference that the language of yours was scientific. Writers tend to draw from childhood experiences a lot, is this what you are doing here too?

AC: It is true that writers go back to childhood. Maybe because it is a time we can only make sense of as adults. It also has to do with how we can trace ourselves to a time that feels so beyond our control. Both the way we stand in the world and the passage of time in childhood feel unique and very different from adulthood. To understand my relationship with language, I needed to go back to the start of my relationship with scientific language, because it still permeates my desire to know the “truth.” Something that can be achieved with math, but not with words. I think I had to look back to understand how I wanted to move forward.

Chapela moved to Iowa in 2014 to pursue a master’s degree in Creative Writing. She had also been accepted to a Graduate Program in Scientific Writing, but she turned down that offer.

ALG: Tell me about your time in Iowa. How did your scientific parents take your decision to detour from your scientific education?

AC: My parents encouraged me to go to Iowa. They didn’t care what I studied; they wanted me to study something, but they didn’t care what. When I explained I didn’t feel excited about being a scientist, they were very supportive. It was probably my second year of chemistry when I told them I didn’t want to be a scientist. My dad asked me, well what do you want to do instead? I had a lot of doubts about writing then. I wasn’t sure I could do it. I didn’t know if I wanted to do it. And my dad told me: “Well, when you can come to us and tell us without a doubt that you are going to sit down and write, then you can drop out of school and write, but until then, just keep studying”. I don’t think I was ready to decide I wanted to be a writer until my first semester in Iowa. Iowa made me who I am as a writer.

ALG: And the writer you are today is very interested in language. Throughout The Visible Unseen, you repeatedly wish that “words” were more precise (like in math). Did you achieve the accuracy you hoped for?

AC: I didn’t. I will never find that accuracy; that’s what writing the book helped understand. Because even the most accurate language, which is science, it’s accurate only when you use math. But math is not enough. We have to put math into words. At some point you get into words, into language. What I have realized is that I will probably write more about this, the problem with words, the problem of wanting to communicate and the shortcomings of communication. Words are not accurate and are not to be completely trusted, but we as humans will keep trying, so desperately trying, to communicate, to understand, to be understood… Words, despite their inaccuracy, seem to be the only thing we have. This fascinates me. Also, if words were as precise as math, maybe we would not need literature. Words are inaccurate and imperfect, as we are. I was never a writer of words before this book. I was a writer of plots and stories. But this book made me obsessed with the problems of language, and I don’t think there’s going back from here.

ALG: You have published fantasy, science-fiction, realistic short stories, essays, poetry… Do you feel a need to explore every literary genre?

AC: Yes and no. If I don’t explore every genre, I’ll be ok. I don’t have a list. But I have found that learning about different genres helps me change the way I think. And then, when I go back to a genre I have already written in, I can build bridges between them. I have new tools and new perspectives. I love having my head refurbished, exploring fresh forms of thinking of the world. Or maybe I just get bored easily. I always need to be in a state of doubt. I need to be amazed. I need to become foreign to myself.

Beyond writing, Chapela also looks for ways to “become foreign” to herself. The most obvious example is her constant study of new languages. She is fluent in German and English. Right now, she is doing a Master’s degree in Asian and African Studies, specializing in Japan and Japanese, but her love of K-Pop has also prompted her to study Korean.

ALG: I have to ask. Are you writing at the moment?

AC: Yes, I’m writing a big novel, a climate-fiction, a cli-fi about love. I hope it’ll be out in Spanish next year.

ALG: And in English?

AC: I still don’t know, but hopefully soon. In the meantime, a translation of my short story “Como quien oye llover” is coming out in Uncanny magazine on October 4.

ALG: And finally, I wanted to ask you about the images from the James Webb Space Telescope. Those images left many of us, scientists and the uninitiated, in awe. We were mesmerized by the beauty of dying stars; overwhelmed with the unknown; humbled by the reminder of our littleness in an infinite cosmos… What did you feel when you saw those images?

AC: I saw the images on Twitter and then watched a video to understand how the telescope worked. The images made me feel melancholic. I thought about everything that is out there that we cannot see; all we don’t know. And maybe that takes me back to your first question, when you asked what was visible but unseen. Those spectacular images made me think of less elegant discoveries, experiments, data, graphics… The little things that scientists unveil but are not divulged through pictures like those. The small steps towards scientific knowledge… that is also visible but unseen. I saw the pictures from the James Webb telescope, and I thought of those everyday moments. That moved me as much as the spectacularity of the photos.

*The Visible Unseen, by Andrea Chapela, translated by Kelsi Vanada, with artwork of Fabiola Menchelli, will be published by Restless Books on October 11, 2022. Preorder is available here.

Alba Lara Granero (El Pedernoso, 1988) es escritora y licenciada en Filología Hispánica y máster en Formación del Profesorado por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Es graduada del programa MFA de la Universidad de Iowa y sus ensayos han sido publicados en Iowa Literaria y otras revistas. Su Twitter: @a_laragranero

Alba Lara Granero (El Pedernoso, 1988) es escritora y licenciada en Filología Hispánica y máster en Formación del Profesorado por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Es graduada del programa MFA de la Universidad de Iowa y sus ensayos han sido publicados en Iowa Literaria y otras revistas. Su Twitter: @a_laragranero

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: September 11, 2022 at 2:30 pm