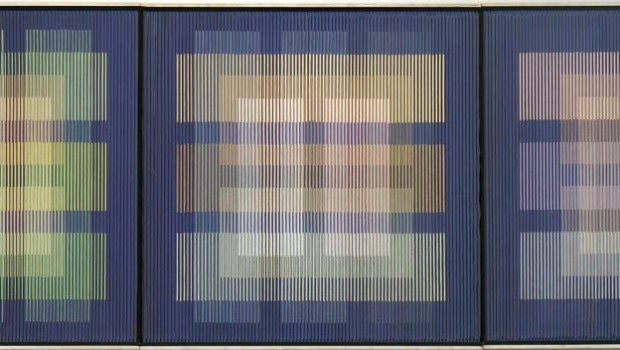

Carlos Cruz Diez

Ni pasado ni futuro, la historia empieza con uno y termina con uno mismo

Rose Mary Salum

Translated from the Spanish by Beth Pollack

Rose Mary Salum: In the long run, Cruz Diez managed to transform not only art in Venezuela but, also worldwide. We know that his pictorial language is the result of years of research and the search to express color in all its movement. How does Cruz Diez come to create his visual language? How does he shape the changing condition of the chromatic experience on canvas?

Carlos Cruz Diez: Arriving at these conclusions is the result of lengthy reflection, very time consuming in readings and failures, because one comes to perfection of what he wants through the accumulations of multiple failures. To arrive at a convenient solution one has to doubt until finally uncovering the structure that confirms and conforms to the concepts that one has of art, or at least what one thinks is art. For me, art was being a painter. I am a painter. I was trained as a painter. I define myself as a painter and the fundamental instrument of a painter is color. It was from that point that I was able to see the possibility of modifying concepts, because what the artist does in his trajectory is precisely to find new projections, new concepts for the spirit and the introduction of knowledge. Because art, as it has been said by great artists, is knowledge, it’s true state of knowledge. Color is not something permanent nor eternal like the notion we, in Western society, have that everything is eternal. Color is a circumstance and all I have found supports this evidence in this changing, mutating and ephemeral condition which is the world of color.

RMS. The pointillists used the dot, why does Cruz Diez use the line?

CCD. One of the starting points for my inquiry were the impressionists, the post-impressionists, fauvism, and artists like Delacroix who saw, in color, the possibility to modify painting and art itself. The pointillists and those subsequent to impressionism discovered and demonstrated that color was changing yet precisely in its contradiction. That is to say, every generation creates a contradiction. The impressionists expressed color in a dynamic condition, but contained it in a static medium. An impressionist wanted to express the fragility of light; however it was captured in an eternal medium; unable to be modified. Pointillism did the same thing. What I attempted to do was to move beyond impressionism and search for the paradox. In that modification of impressionism, I provoked a contradiction, like Malevich’s White on White. That is, it is contradictory to have a metaphysical concept and express it materially through a static medium. Nevertheless, those contradictions, gave me the path to find a medium that also was a creator of ephemeral situations. And beginning with that moment, all my work is based on the construction of ephemeral situations in order to give color its real condition which is unstable, mutable.

RMS. But, why the line? Does it serve to that purpose?

CCD. The line is not an absolutely aesthetic element; it is an element of efficacy. I created points or circles because the line is an essential and unadorned element, unique, to show the metamorphosis, the transformation of color. If these were curved or zig zags they would not add anything to the discourse of color, color as a transformative situation.

RMS. Then Cruz Diez’s art pays tribute to Heraclitus who says that everything is movement.

CCD. Yes, of course. Everything is motion. Color isn’t a static entity, it evolves. One of the things I planned in my work is not to give meanings. Forms have meaning. In my opinion, the only meaning that exists is the dialectics between the spectator and the piece of work. When one looks at those straight lines, they do not have meaning, except that they are the most basic of objects which generates a situation. And, the situation generated by these parallel lines promotes a multiplicity of sensations, perceptions and points of departure for mythification. That is to say they are supporting an occurrence and are the medium for the creation of a myth. These objects serve as a sort of light trap to provoke other notions about color and things.

RMS. Another of your propositions is the autonomy of color. This appears extraordinary to me, and at times contradictory. When one looks at your work, you are caught in its magnetic field; it is the energy that your pictures invite. If one of your intentions is the autonomy of color, and this cannot exist without the spectator, have you established a codependency?

CCD. This is the precisely intention; the contribution of kinetic art to universal art is creating a spectator who participates in the work. From a passive and contemplative attitude, they are led into an active and participative attitude. This involves the spectator in the structure the artist has put into play; because let us not forget that a painting is a reflection, be it a painting of an insignificant flower, of a landscape or by an amateur artist. There we find contained an insight that ranges from the most elemental to the most complex of things, and it is the case of my work that it is a vision of tremendous complexity; it is an expression that has taken a lot of time and refers to many physical types of behavior. Painting stops man’s invention: time. It is the best invention to stop time, an impossible task. And when man figured out that it was impossible to stop time, he invented painting as a testimony to what already had taken place. That is what the canvas is. My purpose with these works is to demonstrate that time does not exist; there is no past or future, there is only the present, and this instant. It is the color making itself in this moment. It is our life. Our life is constructed in the moment; neither past nor future. History begins and ends with one as an individual.

RMS. So then, there is a yearning for eternity; your search is to transcend time.

CCD. Exactly, the search is in accordance with man’s nature. I am trying to propose something that is in harmony with oneself. It is like sound; it is more in agreement with humans because painting is a static medium. However, although I have found the medium static, in order to demonstrate the transformation of color in time, there are other works like pigmentations, there is no medium, it is the same colored space where logos and physical presence create multiple solutions, matrices and, unwritten sensations about the medium that are not present, not there, they are within us.

RMS. Andy Warhol and pop art representatives created a visual language that strongly critiqued the mass production of art. How would you, Cruz Diez, respond to this inquiry when all contemporary artists have studios and create art in series?

CCD. Each artist puts his own reflection into his work. Warhol puts in his work the reflection of his time and society. He bases himself on the assertions of Marcel Duchamp who destroys the academic structure of art. He had a formula and with it lights as the work of art. Andy Warhol again takes it up in order to create a satire and a criticism of his environment. At the same time, he understood something fundamental. This is a media oriented society based on success in the media. This is a contemporary society and like every artist he put his own perspective into play.

RMS. Your studio is a family endeavor where all your children and grandchildren participate. This must be a very poignant experience.

CCD. That was the plan. I tell the young people who surround me that when I fell in love with my wife, I presented her with this life project; I told her that art and life are not separate. I didn’t think about only being a painter from only 10 to 12. I live and die with art and life is the same thing. “Let’s make my work and yours, my children and grandchildren, one thing.” And it has been like that. It has been an experience that happily has followed a good path. Working in a studio was not my own invention; it was done in the XVI century when studios belonged to families and their team. That’s what happened with Sebastian Bach, he and his family composed music and all the Flemish artists had their families and assistants and together they made up a studio. And, that’s what has happened in my studio. It contains many artist friends and they have created their work, because a studio serves so that young people can create their work. I have two granddaughters who are studying art and work there. They are learning and the wealth of what they do remain there. Because creating a painting is not only oil on canvas, there is a lot of expertise and complex production. You have to use the computer; you have to use metalwork, lithography, photography, use a number of trades created as they have in the past. The artists themselves construct their painting, the canvases; they make everything in the studio. I have had to fabricate by hand my own tools that are extremely complex in an almost sculptural way. I don’t want the piece of work to be handmade but to be an event where there is a complex work behind it that helps to shape an artist.

RMS. How has the Chávez regime affected artistic expression in Venezuela?

CCD. There is a new politic, there are some very interesting things going on like the creation of national museums, but the situation is unstable and we do not know what is going to happen there. There is a national project under development. It would not be proper to pass judgment because we will have to wait. A new nation cannot be built in only a few years. You have to wait and see what will happen with time. It could be very advantageous for the country, I believe, it will be good because the country needed change. Venezuelan society needed to be shaken up, it had taken its situation for granted and had forgotten about the poor. Now we have the hope that this will be a good transformation for the country, and of course, if it is for the country, it will also be for art.

Rose Mary Salum: A la distancia, ya que Cruz Diez logra transformar el arte no sólo en Venezuela, sino en el mundo, sabemos que su lenguaje pictórico es el resultado de años de investigación y de la búsqueda, de mostrar el color en todo su movimiento. ¿Cómo llega Cruz Diez a crear su lenguaje pictórico? ¿Cómo plasma en un canvas la condición cambiante de la experiencia cromática?

Carlos Cruz Diez: Haber dado con estas soluciones, con estos resultados, es producto de una reflexión muy larga, muy costosa en tiempo, en lecturas y en fracasos porque uno llega a la perfección de lo que quiere hacer con la acumulación de múltiples fracasos. Para encontrar las soluciones que uno cree convenientes tiene que experimentar mucho, dudar hasta hallar realmente una estructura que confirme y que conformen los conceptos que uno se ha hecho del arte o de lo que piensa que puede ser el arte. Para mí el arte era ser pintor. Yo soy pintor, me formé como pintor y me defi no pintor. Y el instrumento fundamental de un pintor es el color: fue allí donde pude encontrar algunas posibilidades de modificar nociones porque el artista, lo que hace a lo largo de su trayectoria es, justamente, encontrar nuevas salidas, nuevas nociones para el espíritu y la apertura del conocimiento. Porque el arte, como ya lo han dicho grandes artistas, es conocimiento, es el verdadero conocimiento. El color no es algo permanente ni eterno como la noción que tenemos en occidente de que todo es eterno. El color es una circunstancia y toda mi obra pone en evidencia esa condición cambiante, mutante y efímera que es el mundo del color.

RMS. Los puntillistas usaron el punto, ¿por qué Cruz Diez usa la línea?

CCD. Uno de los puntos de partida para mi investigación fueron los impresionistas, el post impresionismo, el fauvismo, todos los artistas como Delacroix, que vieron en el color la posibilidad de modificar la pintura, al arte mismo. Los puntillistas y los posteriores al impresionismo, descubrieron y pusieron en evidencia que el color era cambiante pero justamente en su contradicción, porque cada generación crea contradicciones, el impresionismo crea una contradicción, crea la condición cambiante del color, pero expresándola en un soporte estático. El impresionista quiso expresar la fragilidad de la luz; sin embargo, lo hizo en un soporte eterno: no se modifica. El puntillismo hizo lo mismo. Lo que yo traté de hacer, para ir más allá del impresionismo, fue indagar en una paradoja. En esa alteración del impresionismo propicié una contradicción, como en Blanco sobre blanco de Malevich. Es decir, es contradictorio tener un concepto metafísico y manifestarlo materialmente en un cuadro. Sin embargo, esas contradicciones me dieron la pista para encontrar un soporte que fuera también un creador de situaciones efímeras. Y a partir de ese momento, todo mi trabajo está basado en construir situaciones efímeras para darle al color su verdadera condición que es lo inestable, lo cambiante.

RMS. ¿Pero por qué la línea? ¿Se presta para esos fines?

CCD. La línea no es un elemento estético, en absoluto, es un elemento de eficacia. Yo creé puntos o círculos porque la línea es el elemento esencial y escueto, único, para poner en evidencia la metamorfosis, la transformación del color. Si esas fueran curvas o zig zags, no agregarían absolutamente nada al discurso del color, al color en su situación mutante.

RMS. Entonces el arte de Cruz Diez da la victoria a Heráclito quien dice que todo es movimiento

CCD. Todo es movimiento. El color no es estático, tiene movimiento. Una de las cosas que yo estructuré para mi trabajo es no darle significantes. Las formas tienen significantes. Para mí lo único significante es la dialéctica que se establece entre el espectador y la obra. Cuando mira esas líneas rectas que no tienen ninguna significación, sino son objetos de lo más elemental, eso genera una situación. Y es esa situación generada por líneas paralelas la que provoca la multitud de sensaciones, percepciones y puntos de partida de mitificaciones porque son soportes de un acontecimiento y son los soportes de una mitificación. Esos objetos sirven de una especie de trampa de luz para provocar otras nociones sobre color y sobre las cosas.

RMS. Otra de sus propuestas es la autonomía del color. Esto me parece extraordinario, pero a veces contradictorio. Cuando uno ve su obra queda atrapado en su campo magnético, es la fuerza de atracción de sus cuadros. Si una de sus propuestas es la autonomía del color, pero ésta no puede existir sin el espectador, ¿se ha establecido una codependencia?

CCD. Ese es el propósito porque el hecho de hacer participar al espectador es precisamente el aporte que el arte cinético ha dado al arte universal. De una actitud pasiva y contemplativa, se pasa a una actitud activa y participativa. Lo cual involucra al espectador en el soporte que el artista ha puesto en juego; porque no olvidemos que un cuadro es una reflexión. Así sea el cuadro más insignificante de una flor, de un paisaje, de un pintor de domingo. Allí hay un análisis, de lo más elemental hasta el más complejo, como el caso de mi trabajo, que es una refl exión tremendamente compleja; ha tomado mucho tiempo y se refiere a muchos comportamientos de índole físico. Un cuadro es una propuesta que una persona hace sobre las cosas. Entonces esto ha sido una preocupación de lo que ha sido la pintura. La pintura detiene el tiempo (que es una invención humana). El cuadro es el mejor invento para detener el tiempo, labor imposible. Y justo cuando el hombre se dio cuenta de esto inventa la pintura como un testimonio de lo que ya pasó. El cuadro es eso. Mi propósito en las obras es mostrar que el tiempo no existe, no hay pasado ni futuro, es el presente; es el instante. Este es el color haciéndose en el instante. Es como nuestra vida. Nuestra vida está construida del instante; ni pasado ni futuro. La historia empieza y termina con uno mismo.

RMS. Y entonces hay un afán de eternidad, unabúsqueda de trascender el tiempo.

CCD. Exacto, la búsqueda es que sea acorde con el hombre mismo. Estoy tratando de proponer algo que vaya de acuerdo con uno mismo. Es como el sonido; va más de acuerdo con el ser humano porque la pintura es un soporte estático. A pesar de lo que yo he podido encontrar en un soporte estático para demostrar la transformación del color en el tiempo, hay otras obras como las saturaciones. En éstas no hay soportes, es el espacio mismo coloreado en donde el logos y la presencia corporal genera múltiples soluciones, matices y sensaciones que no están escritas sobre el canvas, no están allí, están en nuestro interior.

RMS. Andy Warhol y los representantes del pop art crearon un lenguaje pictórico que criticaba fuertemente la producción en serie del arte. ¿Cómo responde Cruz Diez a esta demanda cuando todos los artistas contemporáneos tienen talleres y crean el arte en serie?

CCD. Cada artista pone en su obra su reflexión. Warhol plasma en su obra un análisis sobre su tiempo y su sociedad. Él se basa en los postulados de Marcel Duchamp que demuele toda una estructura académica del arte. Tenía una fórmula y con él culminaría la obra de arte. Andy Warhol lo retoma para hacer una sátira y una crítica de su entorno. A la vez, entendió algo fundamental: esta sociedad es mediática. Esta es la sociedad contemporánea. Como todo artista, él puso en juego su reflexión.

RMS. Su taller es un punto de encuentro familiar en donde todos los hijos y los nietos participan. Esto debe ser una experiencia muy emotiva.

CCD. Es un proyecto de toda la vida. A los jóvenes que se me acercan les platico que cuando enamoraba a mi mujer, le presenté este proyecto de vida. Le decía que el arte y la vida no están separados. No es que pensara ser un pintor de 10 a 12. “Yo vivo y muero en el arte y la vida es una sola cosa. Vamos a hacer de mi trabajo y el tuyo, los hijos y los nietos una sola cosa”. Y así ha sido; una experiencia que felizmente ha ido por buen camino. Trabajar en un taller no es invento mío, se hizo en el siglo XVI, los talleres de los artistas eran la familia y su equipo. Eso sucedió con Sebastian Bach. Él y su familia componían la música y todos los artistas fl amencos tenían a la familia, alumnos y asistentes que se formaban en el taller. Y eso es lo que ha sucedido en el mío. Se han formado muchos artistas amigos y han creado su obra. Porque el taller ha servido para que esos jóvenes hagan su trabajo. Yo tengo dos nietas que están estudiando arte y que allí trabajan. Van aprendiendo y va quedando un bagaje de lo que allí se hace. Porque para hacer una pintura no sólo existe el óleo sobre tela, hay muchas tecnologías y hay una elaboración compleja. Hay que usar la computadora, la carpintería metálica, la litografía, fotografía, cantidades de oficios que allí se realizan de la misma manera que sucedió en el pasado. Los artistas fabricaban ellos mismos su pintura, los canvas, todo se hacía en el taller. Yo he tenido que fabricar mis propios utensilios que tienen una extrema complejidad artesanal. Pero no quiero que la obra sea sólo un trabajo artesanal sino un acontecimiento donde uno sienta ese trabajo complejo que está detrás de ello y que es lo que ayuda a formar a un artista.

RMS. ¿Cómo ha afectado el régimen chavista a las expresiones artísticas de Venezuela?

CCD. Hay una nueva política, cosas que son muy interesantes, como la creación de museos nacionales, pero es una situación inestable que no sabemos lo que va a suceder. Hay un proyecto de país que está en proceso. Dar un juicio sería incorrecto porque hay que esperar. Un país nuevo no se construye en pocos años. Hay que esperar para ver qué dará eso con el tiempo. Puede que eso sea muy benéfico para el país, yo creo que será benéfico porque el país necesitaba una transformación; sacudir la sociedad venezolana que estaba muy conforme con lo que era y se había olvidado de la gente más pobre. Ahora tenemos la ilusión de que esto sea una transformación benéfica del país y, por supuesto, si es para el país, también es para el arte.