IN PLAIN SIGHT: FELIX A. SOMMERFELD, SPYMASTER IN MEXICO

FELIX A. SOMMERFELD: MAESTRO DE ESPÍAS EN MÉXICO

C.M. Mayo

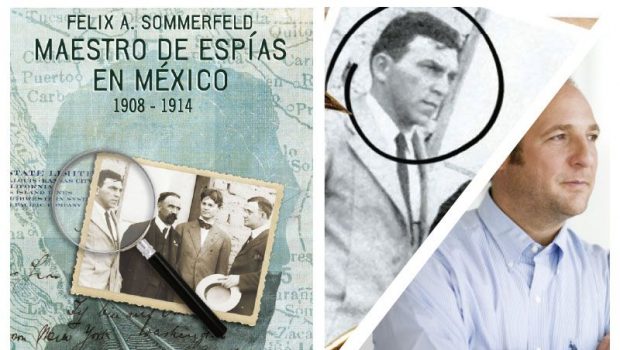

- In Plain Sight: Felix A. Sommerfeld, Spymaster in Mexico 1908-1914 by Heribert von Feiltzsch (Henselstone Verlag, 2012)

It was Mahatma Gandhi who said, “A small body of determined spirits fired by an unquenchable faith in their mission can alter the course of history.” Like Gandhi, Francisco I. Madero was deeply influenced by the Hindu scripture known as the Bhagavad-Gita and its concern with the metaphysics of faith and duty. And like Gandhi, Madero altered the course of history of his nation. From 1908, with his call for effective suffrage and no reelection, until his assasination in 1913, Madero received the support of not all, certainly, but many millions of Mexicans from all classes of society and all regions of the republic. But the fact is, during the 1910 Revolution, during Madero’s successful campaign for the presidency, and during Madero’s presidency, one of the members of that “small body of determined spirits,” who worked most closely with him was not Mexican. His name was Felix A. Sommerfeld and he was a German spy.

We must thank the distinguished historian of Mexico, Friedrich Katz, author of The Secret War in Mexico, among other works, for shining a bright if tenuous light on Felix Sommerfeld. Other historians of the Mexican Revolution have mentioned the mysterious Sommerfeld, notably Charles H. Harris III and Louis R. Sadler in their 2009 The Secret War in El Paso. But it is Heribert von Feilitzsch, by his extensive archival detective work in Germany, Mexico, and Washington DC, who has contributed our most complete— albeit still incomplete—understanding of who Sommerfeld was; Sommerfeld’s relationship with Madero; and his role, a vital one, in the Mexican Revolution.

Writes von Feilitzsch:

“No other foreigner wielded more influence and amassed more power in the Mexican Revolution. From head of security, Sommerfeld took on the development and leadership of Mexico’s Secret Service. Under his auspices, the largest foreign secret service organization ever to operate on U.S. soil evolved into a weapon that terrorized and decimated Madero’s enemies…”

While Sommerfeld was unable to prevent General Victoriano Huerta’s coup d’etat, and his warning to Madero escape arrest came too late, he himself escaped the capital. Continues von Feilitzsch:

“Sommerfeld became the lynchpin in the revolutionary supply chain. His organization along the border smuggled arms and ammunition to the troops in amounts never before thought possible, while his contacts at the highest eschelons of the American and German governments shut off credit and supplies for Huerta.”

Von Feilitzsch reveals that Sommerfeld was reporting not only to the German ambassador in Mexico City, Paul von Hintze, but from 1911 to 1914 to Sherburne G. Hopkins, lawyer and lobbyist par excellence in Washington. Hopkins had initially been brought on board for the cause by Madero’s brother and right-hand man, Gustavo Madero. To quote von Feilitzsch again:

“As a lawyer and lobbyist for industrialist Charles Ranlett Flint and oil tycoon Henry Clay Pierce, Hopkins enabled Sommerfeld to hold the entire keys for American businessmen trying to gain access to the Madero, Carranza, and Villa administrations.”

Sommerfeld was operating at the highest level of sophistication. And perhaps most telling of that sophistication is something surprisingly simple. It is a photograph of him taken in El Paso, Texas during the Revolution, the one that appears on the cover of von Feilitzsch’s book.

In a light-colored suit and dark tie, Sommerfeld stands at Madero’s elbow, protecting his back. On Madero’s opposite side journalists Allie Martin and Chris Haggerty crowd close, seemingly mesmerized by the glamorous revolutionary. Haggerty holds the brim of his hat, pale circle, as if he had only just swept it from his head. But on the other side, just slightly behind Madero, Sommerfeld, bareheaded, craggy-faced, with eyes that belong to an eagle, looks out— a secret service man’s gaze. It is an iconic photograph; those who study the Mexican Revolution will have seen it.

The telling thing, though, is this: that in the archive which has the original, the Aultman Collection in the El Paso Public Library, Sommerfeld, the man with the eagle-gaze, that man who so often appears right by Madero’s side, and here and there in other iconic photographs of the time, including one of the guests at the dinner with Madero and family to celebrate the Battle of Juárez, is unidentified. Or at least he was unidentified there at the time von Feilitzsch wrote his book. In short, during the Revolution, and for over a century to follow, Felix Sommerfeld had been hiding in plain sight. In Plain Sight: the title of von Feilitzsch’s book.

AN ESOTERIC CONNECTION?

I am more grateful than I can say to have encountered In Plain Sight when I did, and I believe that anyone who studies the Mexican Revolution, after reading this book, will say the same. The Mexican Revolution has thousands of facets, of course, but for my own work, the key questions were, Who was Francisco I. Madero? How, in the nitty-gritty, did he pull it off, to lead a Revolution and win the presidency? And, in the face of inevitable and ferocious counter-revolution, how did Madero manage to hold the presidency for as long as he did?

My work, Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution, was prompted by my encounter with Madero’s secret book, Manual espírita (Spiritist Manual). A blend of Kardecian Spiritism, Hindu and other esoteric philosophies, Manual espírita was published in 1911 under the pseudonym “Bhima.”

Never mind what was in Manual espírita, this slender volume with now yellowed pages: the fact that Francisco I. Madero, leader of the 1910 Revolution, had written it and moreoever, published it when he was president-elect in 1911— I could not but conclude that its contents must been exceedingly important to him, and hence, offer profound understanding into who he was and what he stood for.

But my intention here is not to talk about my book about Madero. I suffice to mention that, apart from benefitting so much from the information and insights in von Feilitzsch’s book, I took the liberty of emailing von Feilitzsch a question: What kind of person was this Sommerfeld—might he have been a Spiritist? For there was another German spy working closely with Madero, a Spiritist who turns out to have become a major figure in esoteric circles in the first half of the 20th century: Dr. Arnoldo Krumm-Heller.

Von Feilitzsch was kind enough to permit me to include his answer in my book. He writes:

With respect to Madero’s Spiritism, Sommerfeld not only knew all about it. I am convinced that he was a kindred soul. I have scoured the earth for a book Sommerfeld wrote around 1918, likely under a pen name. I cannot find it. This might be the only possible source for a glimpse into this man’s deepest convictions and emotional structure. Sommerfeld became so close to Madero at the exact time, when Madero must have been under the most emotional pressure. Madero hated bloodshed and violence and exactly that he set off when the revolution started. In his innermost circle were Sommerfeld, [Arnoldo] Krumm-Heller, his wife Sara, and Gustavo, which is documented. … (Sommerfeld was [Sara’s] bodyguard in Mexico City and the last address I have for Sommerfeld reads: c/o Sara Madero, Mexico City. This was in 1930). Just like…Madero, Sommerfeld did not drink, gamble or smoke. In that time and considering the background of Sommerfeld as a mining engineer in the “Wild West,” this is a very unlikely coincidence. In his interviews with the American authorities, he said that Madero was “the purest man I ever met in my life. When I spoke to him, he took my breath away—the child’s faith of this man in humanity.” (Justice 9-16-12) In his appearance before the Fall Committee [of the US Senate] in 1912 he testified: “President Madero is the best friend I have in this world…” Senator Smith “…you became interested in him?” Sommerfeld: “Yes, we became very close friends.” And so on. I definitely hear undertones of esoteric connection. Sommerfeld was very private, rarely allowed a picture taken, and certainly never talked about his faith or personal life to anyone. As someone very rational he kept his distance to others and never described any other relationship in these highly emotional terms. Until I can put my hands on his personal papers or his book, these are only indications but still worth thinking about.

MORE THAN WE MIGHT HAVE DARED HOPE FOR

In many ways Felix Sommerfeld remains a mystery. Von Feilitzsch however, has given us much more than we might have dared hope for: That Felix Sommerfeld was born on May 28, 1879 near Schniedemühl, then in Prussia. As owners of a grain mill, his family was relatively wealthy. Like many Germans in the late 19th century, he had relatives, including brothers, who emmigrated to the United States. As a teenager Felix lived with his brothers for a time in New York. He joined the US Army and received training in Kentucky—then went AWOL, back to Germany. In the first years of the 20th century von Feilitzsch finds Felix Sommerfeld serving in the Prussian cavalry in China during the Boxer Rebellion. Then, he pops up as a mining engineer in Arizona and then northern Mexico—perhaps by then already reporting to the German consul in Chihuahua. Then he’s back to Germany, then, back again in Mexico as a journalist—and all of a sudden, in charge of revolutionary leader Francisco I. Madero’s secret service.

One more of so many things von Feilitzsch brings to us about Felix Sommerfeld: He was Jewish. We do not know his fate, but if he lived into his sixties he may have perished in the Holocaust— or perhaps he disappeared, as secret agents know how to do.

In the Bhagavad Gita, which we know that Francisco Madero read and reread, penciling copious notes in the margins, Lord Kirshna, incarnation of cosmic power, advises the warrior Arjuna to have heart, to do his duty. For Madero, that meant putting aside material concerns and gathering around himself that “small body of determined spirits,” who would help him to alter the course of Mexico’s history. As Madero understood it, those “spirits” would have been both disincarnate and incarnate. Whether and to what degree his chief of secret service shared Madero’s esoteric inclinations remains an open question. But in revealing that, both during and beyond Madero’s lifetime, Felix Sommerfeld was an indispensible member of that “small body,” von Feilitzsch has made a contribution to the history of the Mexican Revolution that is at once disquieting and sensational.

* * *

C.M. Mayo is the author of Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution: Francisco I. Madero and His Secret Book, Spiritist Manual (Dancing Chiva, 2014) which is translated by Agustín Cadena as Odisea metafísica hacia la Revolución mexicana: Francisco I. Madero y su libro secreto, Manual espírita (Literal Publishing, 2014). Her website is www.cmmayo.com

C.M. Mayo is the author of Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution: Francisco I. Madero and His Secret Book, Spiritist Manual (Dancing Chiva, 2014) which is translated by Agustín Cadena as Odisea metafísica hacia la Revolución mexicana: Francisco I. Madero y su libro secreto, Manual espírita (Literal Publishing, 2014). Her website is www.cmmayo.com

*Félix A. Sommerfeld: Maestro de espías en México 1908-1914 de Heribert von Feilitzsch (Planeta, 2016)

Mahatma Gandhi fue quien dijo, “un pequeño cuerpo de espíritus con gran determinación, impulsados por una inquebrantable fe en su misión, puede alterar el curso de la historia”. Al igual que Gandhi, Francisco I. Madero se vio profundamente influenciado por la escritura hindú sagrada conocida como el Bhagavad-Gita y su preocupación con la metafísica de la fe y del deber. Y al igual que Gandhi, Madero alteró el curso de la historia de su país. A partir de 1908, con su llamado al sufragio efectivo y la no reelección, hasta su asesinato en 1913, Madero recibió la ayuda no de todos, ciertamente, pero sí de muchos millones de mexicanos de todas las clases sociales y regiones de la república. Es un hecho que, durante la Revolución de 1910, al momento de su exitosa campaña para la presidencia, y durante el transcurso de su administración, uno de los miembros de este “pequeño cuerpo de espíritus de gran determinación” más cercanos a Madero no fuera un mexicano. Se llamaba Félix A. Sommerfeld y era un agente de la inteligencia alemana.

Debemos agradecer al distinguido historiador de México, Friedrich Katz, autor de La guerra secreta en México, entre otras obras, por alumbrar, al menos de manera tenue, a la figura de Félix Sommerfeld. Otros historiadores de la Revolución mexicana han mencionado al misterioso Sommerfeld, especialmente Charles H. Harris III y Louis R. Sadler en The Secret War in El Paso, publicado en 2009. Pero es Heribert von Feilitzsch, gracias a su extenso trabajo detectivesco de investigación en los archivos de Alemania, México y Washington, que ha contribuido más a nuestra comprensión, aunque aún incompleta, de quién era Sommerfeld; su relación con Madero; y su vital papel en la Revolución Mexicana.

Von Feiltzsch nos relata en su obra:

“Ningún otro extranjero ejerció mayor influencia ni amasó más poder en la Revolución Mexicana. Como jefe de la policía secreta, Sommerfeld propició el desarrollo y la dirección del servicio secreto mexicano. Bajo sus auspicios, operó la mayor organización de inteligencia extranjera que alguna vez operara en territorio estadounidense y se convirtió en un arma que aterrizó y diezmó a los enemigos de Madero…”

Aunque Sommerfeld no podía prevenir el golpe de estado del General Victoriano Huerta contra Madero, y su advertencia a Madero para lograr huir llegó demasiado tarde, Sommerfeld se escapó de la capital. Para continuar en las palabras de von Feilitzsch:

“Sommerfeld se convirtió en la pieza central en la cadena de suministros revolucionarios. Su organización a lo largo de la frontera contrabandeaba armas y municiones para las tropas en cantidades que nunca hubieran sido consideradas posibles, mientras que sus contactos con las más altas autoridades del gobierno en Alemania y Estados Unidos cortaban créditos y suministros a Huerta”.

Von Feilitzsch revela que Sommerfeld le reportaba no sólo al embajador alemán en la Ciudad de México, Paul von Hintze, sino que también, a partir de 1911 y hasta 1914, a Sherburne G. Hopkins, abogado y cabildero par excellence en Washington. Hopkins había sido invitado a la causa de Madero por su hermano y mano derecha, Gustavo. Para citar a von Feilitzsch otra vez:

“Como abogado y cabildero para el industrial Charles Ranlett Flint y el magnate petrolero Henry Clay Pierce, Hopkins le facilitó a Sommerfeld las llaves para relacionarse con empresarios estadounidenses que aspiraban acercarse a las administraciones de Madero, Carranza, y Villa.”

Sommerfeld operaba al más alto nivel de la sofisticación.Y quizá la muestra más reveladora es algo asombrosamente simple: una fotografía tomada en El Paso, Texas durante la Revolución, la que aparece en la portada del libro de von Feilitzsch.

Con un saco de color claro y una corbata obscura, Sommerfeld se ubica muy cercano al codo de Madero, protegiéndolo. Al otro lado de Madero se unen los periodistas Chris Haggerty y Allie Martin, como si estuvieran impresionado por el glamoroso revolucionario. Haggerty palpa el borde de su sombrero, círculo blanco, como si recién lo hubiera deslizado de su cabeza. Pero al otro lado de Madero, Sommerfeld, sin sombrero, con cara chamagoza, con los ojos que parecen los de un águila, observa el entorno, con mirada de un agente del servicio secreto. Es una fotografía icónica; los que estudian la revolución mexicana sin duda la habrán visto.

No obstante, lo revelador es lo siguiente: en el archivo que tiene la fotografía original, la colección de Aultman en la biblioteca pública de El Paso, Sommerfeld, el hombre con la mirada de águila, este hombre que aparece al lado de Madero por aquí y por allá en otras fotografías irónicas del periodo, inclusive en aquella de los invitados a la cena del propio Madero con su familia para celebrar la batalla de Juárez, no es identificado por nombre. Por lo menos, no había sido identificado cuando von Feilitzsch escribió su libro. En fin, durante la Revolución, y por más de un siglo, Félix Sommerfeld se mantuvo oculto en plena vista. In Plain Sight: Ése es el título de la versión original en inglés del libro de von Feilitzsch.

¿UNA CONEXIÓN ESOTÉRICA?

No encuentro palabras para agradecer lo suficiente el haber encontrado In Plain Sight cuando lo hice, y sin duda creo que cualquier estudioso de la Revolución Mexicana, después de leer este libro, diría lo mismo. La Revolución tiene millares de facetas, por supuesto, pero para mí, para mi propio trabajo, las preguntas claves eran: ¿quién era Francisco I. Madero? ¿Cómo, en la vorágine de la época, logró iniciar una revolución y ganar la presidencia? ¿Y, frente a la contra-ofensiva inevitable y feroz, cómo logró mantener la presidencia por el tiempo que lo hizo?

Mi obra, Odisea metafísica hacia la Revolución mexicana, fue inspirada por mi encuentro con el libro secreto de Madero, Manual espírita. Una mezcla de espiritismo karteciano, filosofía hindú y varias filosofías esotéricas, Manual espírita se publicó en 1911 bajo su seudónimo “Bhima”.

No importa tanto el contenido de Manual espírita, este delgado volumen con sus hojas amarillentas; el simple hecho de que Francisco I. Madero lo hubiera escrito— de hecho lo hizo en el año en que inició la Revolución y lo publicó siendo presidente electo en 1911—significa que su contenido debió haber sido de extrema importancia para él. Y por lo tanto, la esencia del Manual espírita nos ofrece una ventana excepcional por comprender profundamente quién era Madero y cuál era su filosofía.

Pero no es mi intención aquí entrar en detalles sobre mi libro acerca de Madero. Lo relevante es mencionar que, aparte de beneficiarme tanto de la información como de la visión del libro de von Feilitzsch, tomé la libertad de enviarle por correo electrónico una pregunta que siempre me inquietó: ¿Qué tipo de persona era Sommerfeld? ¿Pudiera haber sido un espiritista? Resulta que había otro espía alemán muy cercano a Madero, un espiritista quién resulta haber sido una figura destacada el círculos esotéricos de la primera mitad del siglo veinte: Dr. Arnoldo Krumm-Heller.

Amablemente, Von Feilitzsch me permitió incluir su respuesta en mi libro. Dice:

Con respecto al espiritismo de Madero, Sommerfeld no sólo estaba enterado de todo. Estoy convencido de que simpatizaba con él. He exprimido la Tierra en busca de un libro que escribió Sommerfeld alrededor de 1918, probablemente con seudónimo. No puedo encontrarlo. Y ésta podría ser la única fuente posible para vislumbrar las convicciones más profundas y la estructura emocional del hombre. Sommerfeld se acercó mucho a Madero justo en el momento exacto, cuando Madero habría estado bajo la mayor presión emocional. Madero odiaba la sangre y la violencia, y exactamente eso fue lo que provocó cuando estalló la Revolución. Hay documentos que hablan de cómo su círculo de amigos íntimos estaba formado por Sommerfeld, Krumm-Heller, su esposa Sara y Gustavo (Sommerfeld era el guardaespaldas [de Sara] en la Ciudad de México, y la última dirección que tengo de él es ésta: “c/o Sara Madero, Mexico City”. Esto fue en 1930). Al igual que Krumm-Heller y Madero, Sommerfeld no bebía alcohol ni apostaba ni fumaba. En esa época, y considerando el pasado de Sommerfeld como ingeniero minero en el “Wild West”, es una coincidencia muy rara. En sus entrevistas con las autoridades norteamericanas, dijo que Madero era “el hombre más puro que he conocido en la vida. Cuando platicaba con él, me dejaba con la boca abierta: la fe infantil de este hombre en la humanidad”. (Justicia 9-16-12). En su comparecencia ante el Comité de Fall, en 1912, testificó: “El presidente Madero es el mejor amigo que tengo en este mundo…” Senador Smith: “…¿Se interesó usted en él?” Sommerfeld: “Sí, nos volvimos amigos muy cercanos”. Y así. Definitivamente, intuyo algo así como una conexión esotérica. Sommerfeld era muy reservado; rara vez dejaba que le tomaran fotografías, y ciertamente nunca le hablaba a nadie de sus creencias ni de su vida personal. Era una persona muy racional y, como tal, guardaba su distancia respecto a los otros y nunca describió su amistad con nadie más en términos tan emotivos como éstos. Mientras no pueda yo poner las manos en sus papeles personales o en su libro, éstas son sólo conjeturas, pero vale la pena hacérselas”.

LUCES INESPERADOS

Sommerfeld sigue siendo en gran medida un misterio. Pero von Feilitzsch aporta muchas luces inesperadas. Por ejemplo, nos dice que Félix Sommerfeld nació el 28 de mayo de 1879 cerca de Schniedemühl, entonces parte de Prussia. Siendo propietaria de un molino de granos, su familia era relativamente rica. Como muchos alemanes de finales del siglo diecinueve, él tenía parientes, incluyendo hermanos, que emigraron a los Estados Unidos. Siendo un adolescente, Félix vivió con con ellos por una época en Nueva York. Se enlistó en el Ejército de los Estados Unidos, recibió su entrenamiento en Kentucky y luego desertó y regresó a Alemania. Von Feilitzsch descubre que en los primeros años del siglo veinte, Félix Sommerfeld fue parte de la caballería prusiana en China durante el levantamiento de los bóxers. Luego, surge como ingeniero de minas en Arizona y después en el norte de México—quizás para entonces ya reportando al cónsul alemán en Chihuahua. Viaja nuevamente a Alemania, para regresar posteriormente a México como periodista, y de pronto surge como el encargado del servicio secreto del líder revolucionario, Francisco I. Madero.

Una más de tantas cosas que von Feilitzsch nos revela acerca de Félix Sommerfeld es el hecho de que era judío. No sabemos su final, pero es posible, que de haber llegado a sus sesentas, que haya fallecido en el Holocausto. O quizá sus habilidades como agente secreto le haya permitido desvanecerse a tiempo.

En el Bhagavad Gita, que sabemos que Francisco I. Madero leyó y releyó, escribiendo a lápiz en los márgenes notas copiosas, el Lord Krishna, encarnación de los poderes cósmicos, aconseja al guerrero Arjuna tener corazón para hacer su deber. Para Madero, esto significaba abandonar el materialismo y rodearse del referido “pequeño cuerpo de espíritus con gran determinación” que le ayudaría a alterar el curso de la historia de México. Para Madero, estos espíritus hubieran sido tanto descarnados como encarnados. En que medida el encargado de su servicio secreto compartía sus inclinaciones esotéricos permanece una pregunta abierta. No obstante, al revelar que, tanto durante y después de la vida de Madero, Felix Sommerfeld fue miembro indispensable de este “pequeño cuerpo”, von Feilitzsch ha hecho una contribución a la historia de la Revolución mexicana tanto inquietante como sensacional.

* * *

C.M. Mayo es autora de Odisea metafísica hacia la revolución mexicana: Francisco I. Madero y su libro secreto, Manual espírita (Literal Publishing, 2014). Su página web es www.cmmayo.com

C.M. Mayo es autora de Odisea metafísica hacia la revolución mexicana: Francisco I. Madero y su libro secreto, Manual espírita (Literal Publishing, 2014). Su página web es www.cmmayo.com