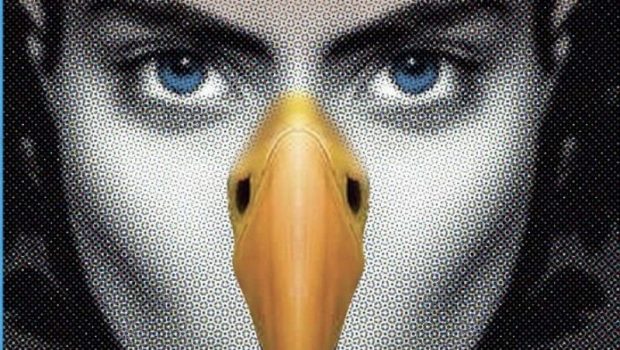

What Happened to Thelma

C. M. Mayo

Thelma did not have one single vice, Gilda insisted. Not one. Thelma did not smoke, she did not chew her nails, she did not gossip, and no doubt she’d only had sex (if she had sex, and Gilda wasn’t going to bet the co-op on it) with Dr. Chavez the gastroenterologist, who was her husband, but he was dead (as of seven months ago, heart attack on the golf course in Jupiter, Florida) — so, how could she? Thelma probably climbed into bed in cotton pajamas, the kind with cornflowers printed on them and little mother-of-pearl buttons all the way up to the chin. OK, Gilda allowed, Thelma did drink, though it was always only one drink — a glass of white wine neatly sipped (Gilda had seen her at intermissions at the Kennedy Center), a taste of champagne to make a toast at the Watergate West New Year’s Party. And yes, she dyed her hair (“Autumn Auburn” — Gilda had seen her with the box at the check-out register of the CVS Pharmacy downstairs) to cover the gray. Was that a vice?

“Don’t forget the face lift”, Jacki said, because it was a famously bad one.

“You could see the scars around her ears”, Gilda said. And to think of it — the little half-moons cut deep in the skin beneath poor Thelma’s earlobes, still red and healing — Gilda burst into loud, sniffling sobs.

“I’ll hold while you get a Kleenex, honey”, Jacki said.

Meanwhile, Jacki went on painting her toenails Very Vermillion, one blue-veined foot up on the rim of her marble Jacuzzi. Jacki was sixty-five years old, though she didn’t look it. Every morning she did an hour of hatha yoga (“breathe”, she would tell herself at odd intervals through her day, “breathe”). An ex-golfer from Dallas, Jacki had been the type to wear pearl clip earrings, but five years ago, when she turned sixty, a niece dragged her to Arizona for a meditation retreat; ever since she’d taken to wearing dangly earrings, the kind with silver feathers and chips of turquoise. Today she wore earrings with tiny strings of silver beads that hung down in a fringe, and as she leaned over — touching her toes with the ease of a cat — they tickled her knee. Not that she didn’t care about Thelma Chavez. It was terrible what had happened to her, truly terrible.

“You know what I was thinking?” Gilda said when she came back on the line.

“Hm”, Jacki said. She was aiming the brush at her little toe.

“I should get a face lift”.

“You’d look more rested”, Jacki offered.

“You really think so”.

“Hm”.

“I’d love to get my eyes firmed up, you know? Maybe a brow-lift, but I’m worried about looking too tight”. Gilda bit into an apple, making a loud crunch.

“Are you eating peanut brittle?”

“Of course not, I’m on a diet!”

“You know”, Jacki said, “Thelma never once went on a diet”.

“Don’t tell me”, Gilda said.

“Thelma read about bacon back in 1981”, Jacki said, “and, bingo, she stopped eating it”.

“Thelma”, Gilda said, though she wasn’t sure what she really wanted to say about Thelma. The thought of Thelma stuck in her throat like cotton.

* * *

It was true, Gilda suffered from peanut brittle binges. Gilda lived alone — Dr. Chavez had divorced her five years ago (it was April 2, 1994, and it wasn’t for Thelma, not yet; though Thelma was already living in Watergate West, in unit 502) — and so, who was to see her? The only one who would come by her apartment without an invitation was Jacki. Jacki lived in the three bedroom penthouse with a view of the river. Just to ride the elevator up there made Gilda feel small, as if, with each passing floor, she were shrinking. When she stepped off, it seemed her voice had become tiny too, high and flighty. In the kitchen — Jacki would brew a pot of sage tea — Gilda couldn’t help comparing her own cracked linoleum to Jacki’s gleaming oak floor, her own original “Harvest Gold” (more aptly, “Congealed Kraft Mustard”) Formica countertops to Jacki’s perfectly fitted slabs of Moroccan green and mocha-speckled granite. Even Jacki’s dishes were prettier, her napkins color coordinated. When the sage tea was brewed, they would sit in Jacki’s living room on Jacki’s white leather sofa, surrounded by walls covered with Jacki’s niece’s paintings, huge canvases of purples and desert yellows and soft rose pinks, all variations of the one over the sofa which was titled “Sedona at Sunrise”. Far below lay the Potomac, a shimmering belt of silver. Seabirds whirled by, and geese, and flocks of starlings. Sometimes, as if it were just another bird, the Presidential chopper would roar by, its tail ruddering in the wind. (Hiya Bill”, Jacki would always say, with a vague nod over the rim of her mug). And so it depressed Gilda to ride the elevator back down to the second floor to her own one bedroom with a “city view” — which meant cars whizzing by and the boring beige slab of the Howard Johnson’s. Always her apartment lacked light and it smelled stale, of cigarette butts and the “Carpet Fresh” powder her maid shook out too much of on the carpets. As for the peanut brittle, it was the cheap kind from the Safeway downstairs that tasted of imitation butter and made her fingers slippery with grease. Gilda would sit in her ex-husband’s armchair with the box open on her lap, the TV on loud so she could hear it over the crunching. Such a bliss of oblivion: the sugar coursing into her veins like opium, the peanuts all mealy in her mouth. Crunch crunch crunch crunch.

But now Gilda was on a diet — apples, lettuce, skinned boiled chicken, and can after can of Diet Coke. She had been on a diet since the last time she saw Thelma, which was two weeks ago in the elevator — one week before it happened. Thelma had just had her hair done, and she was coming back down to check her mail. Gilda could tell, because Thelma did not have her coat on — all Thelma wore was a baby-blue St. John knit dress and a string of pearls. Outside (Gilda had seen it from her balcony), a freezing rain was driving down like darts.

“Oh”, said Gilda. She suddenly felt very fat in her belted raincoat. She drew her teeth back in a smile. “How nice your hair looks”.

Indeed, Thelma’s hair looked smooth, a perfect helmet of Autumn Auburn. Her face was also smooth, and if the skin was drawn too tightly over the bones, no matter: Thelma owned an expression as serene as a minor saint. On her hand — she held her keys with simple grace, as if they were a rosary — the modest band of gold. (Seven months his widow, and Thelma still wore it, Gilda thought. Her own she’d dropped down the trash chute).

“Thank you”, Thelma said.

And then, when the elevator came to the lobby, Thelma said, “Goodbye.”

* * *

Jacki saw Thelma more often, because she went to the Health Club in the basement of the Watergate Hotel next door. You saw everybody there: Senator Kelly on the LifeCycle, Liz Dudley on the rowing machine, Mrs. Edelman (bless her, she’d suffered a stroke) in her bathing cap with the ruffles and the chin strap, walking slowly, her chicken-thin arms making angel wings from one side of the shallow end to the other. Dr. Chavez had been keen for the StairMaster. Right up until his final golf vacation in Jupiter, Florida, he used to pump away from 6 to 6:30 pm every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Toward the end of his half hour he’d be half slumped over like a Sherpa with big triangles of sweat on his “GO GEORGETOWN” T-shirt; but when the timer hit 30, pum! He’d punch the STOP button and fling his little towel around his neck. “StairMester Time”, Dr. Chavez liked to say, his eyebrows bouncing up and down like Groucho Marx’s, “it ez de slowest time known to man”.

It gave him firm glutes, Gilda would allow; otherwise it didn’t do him any good. As soon as she said this, however, she felt like a big rock had dropped into her stomach. (How could she say such a thing?)

“But now Thelma”, Jacki said. “she started lifting weights with the trainer, and you could see her skin just glowing”.

They were on the phone again. Jacki clamped the receiver between the vise of her shoulder and one ear. She was standing naked in her bathroom. For a sixty-five year old, Jacki didn’t look bad. She would have liked to but she couldn’t see herself, because her bathroom was billowing with steam.

“I’ll bet Thelma never strained”, Gilda said. Gilda was sitting in her kitchen, tipping her cigarette ash into an empty can of Diet Coke. On the “Harvest Gold” counter, by the telephone, was a large burn mark. She’d made it the week they’d moved in, in 1972.

“She never built up that stringy muscle”, Jacki said.

“I hate stringy muscle”, Gilda said.

“Hm”, Jacki said, knowing that her own were not stringy. How she adored her bathroom, all mirrors and cool, cream-colored marble. Her Jacuzzi was filled now, just above the nozzles. (“Gosh”, Gilda had marveled when she first saw it, “you could drown your elephant in that”.) The towels, piled high in a hand-woven Hopi basket, were white and fluffy, fresh from the dryer. The Vita Bath — Jacki squeezed in the entire bottle (Gilda heard it, plipilyplipily) — smelled like newly mown grass.

“I should start going again”, Gilda said. Gilda was 40 pounds overweight. All of her exercise clothes were tight.

“Hm”, Jacki said. She dipped her hand in the water. (The Jacuzzi, the contractor estimated, weighed 2,000 pounds when full. “I ain’t making no guarantees”, he’d said, and he made it plain, he didn’t want to install it).

“My doctor says my blood pressure is high”, Gilda said. She tapped some more cigarette ash into the Diet Coke can.

“Hm”, Jacki said. (She reminded herself, breathe.)

“I guess I’d feel better if I made myself walk on one of those treadmills”, Gilda said.

“You would,” Jacki said. (Just breathe.)

“I don’t want to have a stroke or anything”, Gilda said.

“Hm”, Jacki said. She was fond of her neighbor, she really was. But sometimes she just wished Gilda would shut the flippetydoodah up.

* * *

A little while later, Jacki’s niece called from Arizona. Her voice — a high-pitched flute-like voice of a child, though she was nearly thirty — sounded so clear she could have been calling from the next room. In fact, she was calling from her studio on the outskirts of Sedona, a strange fire-colored place of red rock and cactus and quick slithering things. (And, Jacki thought, too many kitschy art galleries.) It would still be light there. Here, in the night, Jacki lay floating in her Jacuzzi, her knees two glistening islands in a sea of warm, pale green bubbles.

Her niece wanted to tell her about her new meditation teacher, a woman who also happened to channel a Light Entity named Zeldklar. “Zeldklar says your mind can see everything. When you meditate, you can learn to make your mind, like, fly all around the universe”.

“Well”, Jacki said. “You don’t say”. There was something hard and slicing in her voice — but she was trying, she really was. Other than this niece, no one else in her family would still speak to her.

“Anybody can learn to do it”, her niece said.

“You really think so”, Jacki said, but of course she didn’t think so, and only partly because she had her doubts about this new meditation teacher. The last meditation teacher — the one who’d led the retreat Jacki had attended with her niece — had such a kind face, soft and round like a doe-eyed Buddha. “Your mind expands with your compassion”, the teacher had said and then — ting – rung a little silver bell. It did make sense — yes, Jacki had realized as she sat there in the “lotus” position, her eyes closed and hands pressed lightly together — yes. But the problem was, in her heart, Jacki was still the little girl who thrilled to tell lies and steal things (Marcy McFilbert’s stuffed Easter bunny, the teacher’s change purse). One time — how can it possibly have been almost sixty years? — Jacki had plucked the legs off a daddy longlegs spider one by one by wriggling one until there was nothing left in the palm of her hand but a dot. “Whatchit!” she’d flicked it with her thumb at Marcy McFilbert — and then told the whole class it was Marcy’s booger.

“Zeldklar says that time and space are an illusion”, her niece said.

“You don’t say”, Jacki said, though she wondered for a moment if this might be true; after all, her own life seemed to her packed and warped and pulled into tight, painful knots. Dr. Chavez (no one called him Ermenegildo, not even Gilda when she was married to him) Jacki remembered as if she’d seen him last night: his breath like hot coffee, the sandpaper feel of his face, the muscled weight of him as he rolled over the coolness of her sheets. Dr. Chavez might as well have collapsed on the golf course in Jupiter, Florida this morning as seven months ago; he might as well have been sitting in his livingroom watching TV with Gilda; for that matter — Jacki felt it like a certainty — he could have been dressed for the Kennedy Center, riding down in the elevator with Thelma. “Oh”, Jacki sighed suddenly. “Poor Thelma”.

“What happened to Thelma?” her niece asked.

“What happened to Thelma?” Jacki sent the question hurtling back across the continent as she slipped down until her knees disappeared into the warm, pale green water and she could feel the water lapping at the hairs on the back of her neck. She had to turn her cheek to keep the telephone above the suds. Breathe, she told herself, as she took a long deep breath that, let out, sounded like another sigh.

“Well?” said her niece.

“Well”, said Jacki. “Why don’t you ask Zeldklar?”

There are so many bizarre ways to die, Gilda thought. This was later, when she was lying in her bed still thinking about what had happened to Thelma. In college Gilda had read a short story about a man whose father died when a pig fell on top of him. The father really suffered, because though his pelvis was crushed into his abdominal cavity, it took a long time for him to die. And then the son suffered too because he was so embarrassed about the way his father had died. In the story everyone asked, or maybe — Gilda couldn’t remember — the story ended when someone finally asked, “so, what happened to the pig?” And how about the Indonesian sushi chef who swallowed 696 goldfish and one of them popped out his nose but anyway he died of bloat. (She’d read about that just the other day at the Safeway check-out.) Once she saw a TV show — it was The Twilight Zone — about a man who drove out by himself to a remote villa. No one was there; all the furniture was draped with sheets. He stepped into the elevator. The doors shut; with a loud grinding it began to rise, and then with a clank it stopped. He punched all the buttons; he slammed at them with his fist. And then he screamed and screamed — because he knew no one would find him, not for months. Well, Gilda decided as she tucked the blanket up just beneath her chin, some things you could avoid. If you had the sense.

• This story was published in Chelsea, issue 70/71, December 2001, Special issue on “VICES”.

Posted: April 2, 2012 at 5:45 am