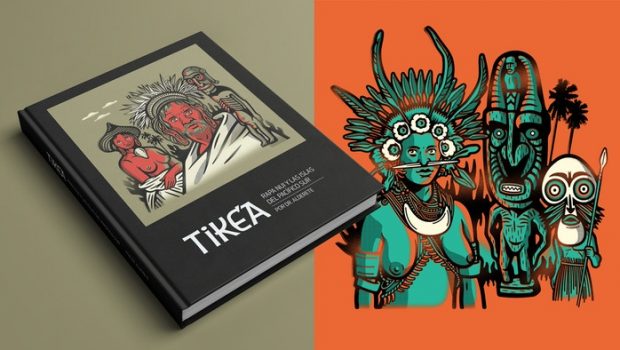

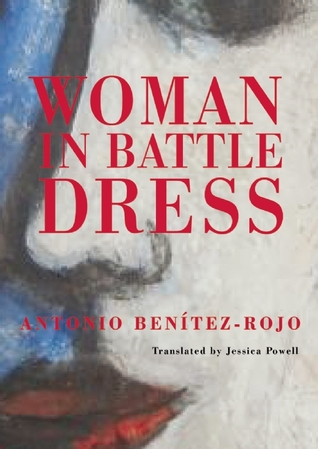

Woman in Battle Dress

Antonio Benitez-Rojo

Aboard the Schooner

And so, in three days you’ll disembark in New Orleans. Four, at the most, if the wind fails. As hard as you try to take heart, you can see no reason that you should be any better received there than you were in Cuba. What they know of you in New Orleans is nothing but secondhand gossip spread by travelers from Havana; rumors repeated by sailors and merchants who, hoping to amaze their listeners, turn every drizzle into a downpour, every chicken’s death into a horrifying murder. God only knows what abominations they are telling about you there! If there’s one thing you’re sure of, it’s that the dock will be full of gawkers hurling insults. Some will even spit at you. There’ll be the usual hailstorm of eggs and rotten vegetables. There will even be those who’ll try to pinch your backside or claw at your face. Master and slave, lawyer, barber, shoemaker and tailor, each and every one of them will heap their own guilt and resentments onto you. The saddest part of all is that there are bound to be some good women among the crowd, women who’ll condemn you without even knowing why. Their minds constricted by ignorance and prejudice, they’ll see you only as an indecent foreigner, a degenerate; never a friend. How well you know their accusatory cries. They have dogged you from one end of Cuba to the other, from Santiago all the way to Havana. The only difference is that this time they’ll humiliate you in English, and even in French, your own mother tongue. What you fear most, what you’ve begun to obsess over, is that moment when you’ll step off the boat—your first steps onto the dock, exposed to all those stares, those hungry eyes fixed upon you, wishing to strip you bare. Today, more than ever before, you understand the cruel shame suffered by so many women who, on their way to the bonfire, the guillotine, the hangman’s noose, or the executioner’s axe, were paraded through an excited crowd, lathered up by the promise of a spectacle. It’s true that, in your case, there’s never been talk of a death sentence, but you’ve been insulted so repeatedly that the thought of being subjected to public ridicule all over again has come to feel intolerable. Despite all that you saw during the war—the battlefields of Austria, Russia, and Spain, among others, you’ve never managed to get used to the insensitivity of human beings, especially those in so-called “polite” society. And of course, the satirical bards of New Orleans will have their verses at the ready. Eager to show off their wit, they impatiently await your arrival. Later, they’ll publish their rhymed couplets in the newspaper, attaching to them names like Sophocles and Euripides. Poor devils, they don’t even know that, had you lived in those classical times, your glories and miseries might have provided the worthy inspiration for some famous dramatic poet. But no, now that you think back on your reading, you realize that you don’t fit as a character in a Greek tragedy; Electra, Ariadne, and Clytemnestra have nothing whatsoever to do with you. Only a woman of your times could understand you completely, perhaps a Madame de Staël, Swiss-born like you, with a free spirit to match your own. But the baroness has been dead nine or ten years by now and you can think of no one else who might defend you with her pen—that is to say, to do you justice for posterity’s sake. If only you had half the talent of that Mexican nun whose works you read in prison, what immortal verses you would compose, what sage letters you would write! What other woman knows what you know of men, what other woman knows their bodies and souls as well as you! And what’s more, who could possibly define a woman’s place better than you, you who have proven yourself within the most exclusive of men’s worlds? But God did not grant you the gifts of a poet and you will never be the one to elegantly describe the ups and downs of your life. Face it, Henriette; your fate is sealed. You have nothing left to hope for. Even if you manage to go down in history, it will be as a libertine, in the best of cases, an infamous impostor. Judges, scribes, witnesses, registries, briefs, signatures, seals—all of the instruments of jurisprudence have allied themselves against you; they have omitted any favorable depositions and exaggerated those that malign you. They have judged you hastily, with single-minded determination, as though you were an abhorrent social error that must be rectified immediately and never allowed to recur. Your past has been meticulously dissected, disputed, and criticized, you’ve been reviled as a negative example, too dangerous in a world held in thrall to outmoded ideas from fifty years ago. And so, your truth—all that you have left—will remain buried alongside your bones in some Louisiana cemetery. And it will all begin again three days from now, perhaps four. Imagining yourself humiliated all over again by the throngs, seeing yourself disembark with your head shaved practically bald, wearing the threadbare habit you inherited from a nun, dead of yellow fever, you know that you can’t take it anymore. You have reached your limit. In Santiago de Cuba, when they threatened to parade you along the main thoroughfare, dressed in a shift and mounted atop a donkey, you considered killing yourself right there in your cell. What a pity that you didn’t go through with it, Henriette. What a pity. And now, when all of your efforts and good deeds have proven worthless, when your entire body aches from so many restless nights, you wonder why you ever asked the ship’s captain for a pen and paper. What you write at this very moment may well prove to be your final letter, your final act. Yes, a letter to yourself. And perhaps of farewell.

***

You take up the pen after reading what you wrote last night. How fickle emotions are! All it took was to be allowed on deck to take in the beautiful morning and to exchange a few pleasantries with Captain Plumet to transform your emotional state, though physically you’re still slow and aching. And really, how vain you are, my friend! Did you actually think that those “glories and miseries” that you so boasted of yesterday—with the rhetorical style of a provincial lawyer, no less—would merit the attentions of a famous writer? Were she still alive, Madame de Staël would not have even bothered to listen to your story. You’re no Joan of Arc, after all! Only women of high moral principles should become the subject of literature. The perfect heroine should act selflessly, unaware of the personal consequences of her actions. If her behavior is praiseworthy, it is so precisely because it cannot be bought or led off course. These are the women’s names that deserve to be etched in stone, certainly not yours. I’ll grant that you’ve never been lacking in presence of mind or in perseverance, but, as painful as it may be to admit, you must recognize that if you have defied the law for many years, you did it first out of compassion, then led by ambition, and finally, for love. It’s not that you’ve stopped believing that both the courts and the public have judged you maliciously, but you must confess that it was your excessive self-confidence, or better, your vanity, that landed you in prison. This time you gambled and lost, and that’s all there is to it.

And now you’ve begun to wonder what the mayor of Havana has written in your convict’s passport. Your future in New Orleans depends, in good measure, upon what it says. Fortunately, he didn’t seem ill-disposed toward you last year when he visited the women’s hospital. You may also count on support from Bishop Espada, who has proved himself sympathetic. In any case, it’s likely that you’ll find out what it says tonight, since the cheerful and gallant Captain Plumet—something about him reminds you of your uncle—has invited us to dinner, and it is he who safeguards all of our documents. You speak in the plural because on deck you met two other deportees: a mulatta suspected of witchcraft and a melancholy whore of about your age, both from New Orleans. Although you were unaware of their presence on board the ship, they were certainly aware of yours. The respect they have for you is strange. To judge from their words, you have become rather famous among women of ill-repute. You could even say that they envy your celebrity. Imagine! But now you must overcome the febrile exhaustion that has come over you and try to fix yourself up to look at least passably presentable; your two admirers have outfitted you with clothes, makeup, shoes, even a wig. How many years has it been since you last dressed as an elegant woman?

(Three hours later.) Undeniably, Captain Plumet is the spitting image of your Uncle Charles: the same prominent jaw line, the curved nose, the suntanned face, the sparkling blue eyes, and that desperate, roaring laugh that he adopted in his last days. Perhaps this is why, yesterday, you got up the nerve to ask him for writing materials. In any case, my friend, you have little to be happy about. Your passport reads: “Enriqueta Faber Cavent. Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, 1791. Subject of the French Crown. She has served four years of reclusion and service in the Women’s Hospital of Havana. She has committed the following crimes: perjury, falsification of documents, bribery, incitation of violence, illegally practicing medicine, imposture (pretending to be of the masculine sex), rape of a minor, and grave assaults against the institution of marriage. She has been forbidden to reside in Cuba or in any other territory under the Spanish Crown. She is hereby remanded to the authorities in New Orleans.”

You had it right yesterday: your fate is sealed. And more than sealed, signed by the mayor and approved by both the governor and the captain general. Even so, some hope remains. Plumet showed you a sealed letter in which, according to him, the bishop asks the Mother Superior of the Sisters of Charity in New Orleans to take responsibility for you. Does this mean that you’ll have to live in a convent and go on wearing a nun’s habit? What do they want from you? How long must you wait for your freedom? Plumet had shrugged his shoulders; he knows nothing. He would like to do something to help you, but his hands are tied. Years ago, when he commanded one of Jean Laffite’s ships, he would have hidden you in an empty barrel and that would have been that. But everything’s changed since the war. The port authorities are ever more persnickety and even the slightest irregularity can cost a captain his license. He told you this in a rush, as if hoping to forestall any further conversation on the topic, while urgently ushering you out of his quarters so as to be left alone with Madeleine and Marie, since as far as womanizing goes, well, that’s another thing he has in common with your uncle. In any case, you may at least be grateful for his good intentions and an excellent dinner.

***

How peculiar that here, in the middle of the ocean, aboard this aging schooner transporting goods as ordinary as leather, tobacco, and mahogany, your old dream about Robert should have returned. There was a time when the dream recurred two or three times every year. Later, as if the names Enrique and Henri had erased Henriette’s past, it returned less and less frequently until finally disappearing from your nights altogether. In any event, the dream came back to you exactly as before. Although now that you think about it, there is one important difference: within the dream you were aware that you were dreaming the same dream you had dreamt before. So much so that, seeing yourself once again in that strange and desolate room, you tried to leave so as not to feel the sadness of Robert’s arrival. But, no matter how you tried, you were scarcely able to move your limbs, and then suddenly, there he was, his frame filling the dark recess of the doorway, awaiting your cry of surprise so that he could shyly enter the room. As always, he is dressed in his exquisite Hussar’s uniform—Hungarian culottes made of blue cloth, red Dolman with gold fringe, bearskin hat topped with a long feather, tall calfskin boots, and, draped over his left shoulder, the splendidly embroidered fur cloak. His curved saber hangs from his wrist, tied on by a silk cord. His other hand holds the reins of Patriote, his favorite mount, the saddle covered with a leopard skin given to him by Field Marshal Lannes. Suddenly Patriote startles; his eyes bulge with fear. Robert tries to calm him, but the horse struggles to go back outside and Robert lets him go with a gesture of resignation. From the moment you saw him, you realized that he’d grown taller since the last time you had the dream. He also seemed thinner, although perhaps not, perhaps you had merely misjudged after seeing him so tall alongside Patriote, who, for some reason, was the same size as always. Now Robert examines the room’s bare walls. His gaze moves slowly over the dimly lit corners, the beams of the ceiling, the grand silver candelabra, filigreed in dust and cobwebs, which stands on the mantelpiece above the empty fireplace. There are no candles in this candelabra. The hazy glow that floats in the room does not come from any visible source of light. Although Robert has seen you—or better, has moved his inexpressive gaze over you—he has not noticed you; to him, you must be like a sort of reflection or a transparent presence. Knowing that now you can walk, you decide to get up from the bed. A sense of infinite compassion impels you toward him. Robert has grown so large that, although you stand on tiptoe, your lips barely brush against the cross of the Legion of Honor that he wears on his chest. “Ah, it’s you. Doesn’t it seem that spring is awfully late to arrive here in Foix?” Upon hearing his words, you realize that he doesn’t yet know that he is dead. You wonder if you should tell him, but decide against it. Whatever his condition, he does not appear to be in pain. Confused by this situation, you manage only to lead him by the hand toward the bed. Curiously, his hand is not cold. You notice that he has recently shaved and that his tremendous mustache has been newly waxed. Robert allows himself to be undressed like a child—you always marvel at seeing him naked. After untying the saber from his wrist and removing his cap, you take your time unbuttoning his clothing. At last you lay him down across the bed, loosen the braids against both sides of his face, and pull off his shiny black boots and tight-fitting culottes. His body is intact. There is not even a trace of his old scars. A faint opalescent glow emanates from his long and conspicuous penis, resting flaccidly against his left thigh. “Ah, it’s you. Doesn’t it seem that spring is awfully late to arrive here in Foix?” End of the dream.

The sun was just rising when you came up on deck. You were dressed as a woman and wearing Madeleine’s wig. This is how you’ll disembark tomorrow in New Orleans. To avoid thinking about Robert and the dream, which always unsettles you, you distract yourself by watching the bustle of the sailors. What a complex thing, a ship! Even Plumet’s small and aging schooner, with its wooden hull, rigging and sails, seems an indecipherable puzzle. You assume that each and every one of the ship’s innumerable parts has a specific name, something like the drugs in a pharmacopeia. That large, deep sail could be called laudanum, and the triangle of sailcloth that they raise at the prow could be eucalyptus, beneficial for respiratory ailments. This is how Madeline found you, immersed in your little game. Marie, the mulatta, was in her berth, suffering from seasickness. Madeline is a dispirited sort. She is also younger than she appears. Hard living has withered her face and set its expression in a deep scowl. She moves like a sleep-walker. Were you to choose one word to describe her it would be this: exhausted. You can imagine her used up breasts, her anus worn to shreds from the arduous work of making a living off her body. As she tells it, both she and Marie traveled to Havana with the Théâtre d’Orleans opera company. Madeline doesn’t sing, but the manager needed an obsequious woman with loose morals and a passing knowledge of Spanish to hand out programs to passersby. Marie doesn’t sing either; she joined the troupe as a hairdresser. Why did they decide to stay in Cuba? For the same reason you did, Henriette: to make money.

A cabin boy, the very same one who tried to enter your cabin last night and whom you dispatched with a slap across the face, interrupted your conversation. “Captain Plumet has invited you both to have breakfast with him,” said the boy, scarcely looking at you. When you made as if to follow him, Madeleine took you by the arm; she had something to discuss with you. Her proposition, delivered quickly and nervously, rendered you speechless with surprise. You knew, of course, that she despised her line of work and held a very poor opinion of herself, but it had never even crossed your mind that donning the habit of the Sisters of Charity would seem so marvelous to her. Madeline, simply put, wanted to be you, wanted to trade the whorehouse for the convent. “But in order to exchange passports we would need Captain Plumet’s help,” you told her. “It is already guaranteed,” replied Madeline. “I bought it at a very good price last night. Truth be told, it’s not a problem for him at all. They put him in charge of transporting three women, and three women will disembark at the dock.” “And Marie?” you asked. “She’s like a sister to me,” Madeline smiled. “She’ll shave my head to look just like yours.”

And so, my friend, you shall arrive in New Orleans with a new name, Madeline Dampierre, and the good nuns at the convent will receive a false Henriette Faber. Damned if this isn’t a true comedy of errors! Well, you wish them both the best of luck. Naturally, Plumet’s complicity came at a price, which turned out to be exactly the one you had expected. How simple it is to manipulate certain types of men!

Hours later, your head fuzzy and aching from so much wine, you went up on deck to take in some fresh air. The moon was full. When you leaned out over the gunwale to feel the ocean spray, you saw a line of dolphins following behind the boat. Their polished backs, bathed in moonlight, looked like enormous silver coins rolling edgewise among the waves. Surface. . . . Submerge. . . . Surface. . . . Submerge. What else is life but a continual cycle of abundance and scarcity? One way or another, you’ll sort things out when you get to New Orleans. Nothing could be worse than that retreat from Moscow in which nine of every ten who marched alongside you had died. And now you think again of your dream about Robert. Could it be some kind of sign? Oh, my beautiful and distant Hussar, what times we had together! How I missed you, how I wept for you! Rest in peace in my dreams. You will always be with me. For better or for worse, I owe to your death much of what I have been, what I am today, and what I forever will be.

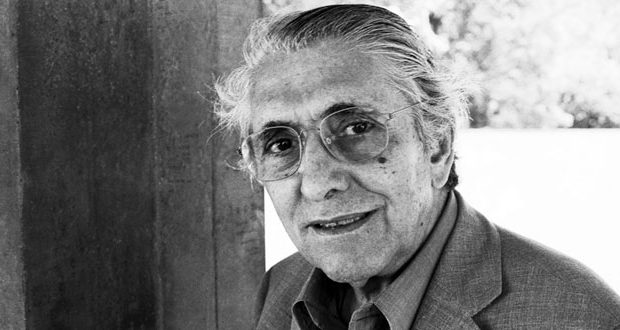

Antonio Benítez Rojo (March 14, 1931 – January 5, 2005) was a Cuban novelist, essayist and short-story writer. He was widely regarded as the most significant Cuban author of his generation. His work has been translated into nine languages and collected in more than 50 anthologies.

Antonio Benítez Rojo (March 14, 1931 – January 5, 2005) was a Cuban novelist, essayist and short-story writer. He was widely regarded as the most significant Cuban author of his generation. His work has been translated into nine languages and collected in more than 50 anthologies.Posted: May 12, 2016 at 10:05 pm