20 MAY

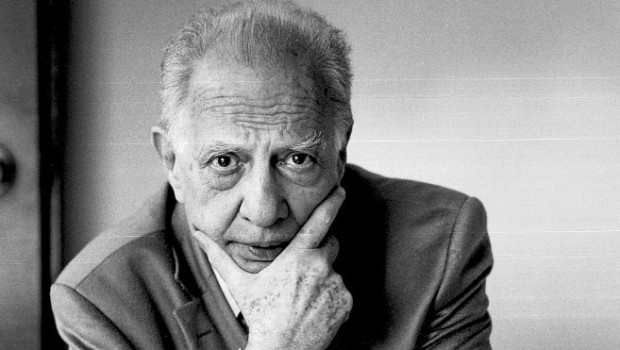

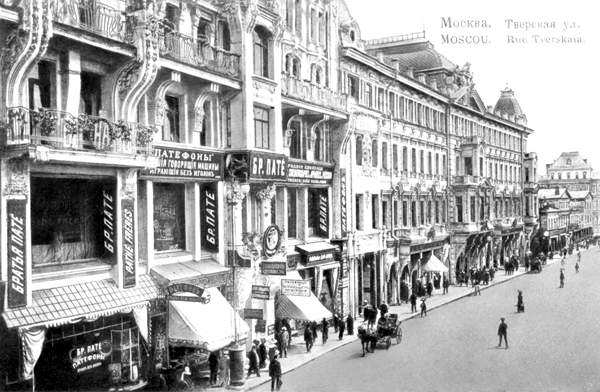

Sergio Pitol

I woke up with a cold; my head kills me at times. I get by with aspirin, and that has allowed me to do many things today. I recall my first visit to Moscow in late 1962, during a harsh winter, they called it the winter of the century, and I believed them. Later I heard of at least a dozen colder winters of the century in Eastern Europe.Those were the days of Khrushchev. I hear the same kind of hopeful talks again then sense the same fear that the apparatus, the army, the police agencies, the nomenklatura, and—let’s be honest—the apathy of the people will annihilate what has already been done and close the doors to the future for a long time. The Arbat, the picturesque old quarter, where Pushkin’s house still stands, not far from our embassy, is an active example that winds of change are blowing: cafés, restaurants, young people dressed in brightly colored clothes, with guitars and books under their arm. They tell me that a carnival was held here for the first time in Moscow since the 20s. It was organized by young people who dressed in masks and costumes of their own making; the festival turned out to be so entertaining that the people of neighborhood were speechless, no one imagined that this could be possible. It seems insignificant, but for fifty years young people lacked possibilities as simple as that, except members of the Young Communist League, who at different levels, whether by geography or guild, organized public activities, but always with a civic purpose: day of the teacher, of the woman, of the athlete, fiftieth anniversaries or centennials of the birth or death of a leader of the labor movement, a hero, or a historical event.Young people were left with other possibilities for escape: the cult of friendship, sex for some, religion for others, culture for many, but above all eccentricity. Faced with centuries of cruelty and an unrelenting history, against the robotic nature of contemporary life the only thing they have left is their soul. And in the Russian’s soul, I include his energy, his identification with nature and eccentricity. The achievement of being oneself without relying too much on someone else and sailing along as long as possible, going with the flow.The eccentric’s cares are different from those of others—his gestures tend toward differentiation, toward autonomy insofar as possible from a tediously herdlike setting. His real world lies within. From the times of the incipient Rus’, a millennium ago, the inhabitants of this infinite land have been led by a strong hand and endured punishments of extreme violence, by Asian invaders as well as their own: Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, Nicholas I, Stalin; and from among the glebe, among the suffering flock, arises, I don’t know if by trickle or torrent, the eccentric, the fool, the jester, the seer, the idiot, the good-for-nothing, the one with one foot in the madhouse, the delirious, the one who is the despair of his superiors. There is a secret communicating vessel between the simpleton who rings the church bells and the sublime painter, who in a chapel of the same church gives life to a majestic Virgin greater than all the icons contained in that holy place. The eccentric lends levity to the European novel from the eighteenth century to the present; in doing so, he breathes new life into it. In some novels, all the characters are eccentrics, and not only they, but the authors themselves. Laurence Sterne, Nikolai Gogol, the Irishmen Samuel Beckett and Flann O’Brien are exemplars of eccentricity, like each and every one of the characters in their books and thus the stories of those books.

There are authors who would be impoverished without the participation of a copious cast of eccentrics: Jane Austen, Dickens, Galdós, Valle-Inclán, Gadda, Landolfi, Cortázar, Pombo, Tomeo, Vila-Matas.They can be tragic or comical, demonic or angelic, geniuses or dunces; the common denominator in them is the triumph of mania over one’s own will, to the extent that between them there is no visible border. Julio Cortázar creates a kind with which he constantly plays: los piantados, the nutcases, those characters outside the constraints of the world, with two registers, one of a genius and the other of a simpleton. There are authors and characters whose eccentricity in this time of yuppies would have led them to a cell in an insane asylum or a retirement home with medical treatment if their finances allow it. The world of the eccentrics and their attendant families frees them from the inconveniences of their surroundings. Vulgarity, ungainliness, the vagaries of fashion, and even the demands of power do not touch them, or at least not too much, and they don’t care.The species is not characterized solely by attitudes of denial, but rather its members have developed remarkable qualities, very broad areas of knowledge organized in an extremely original way. Dealing with friends of this kind can at first be irritating, but little by little it develops into an unavoidable necessity. To the eccentric, other people, from outside his circle, are difficult, pompous, pretentious, and insufferable for a thousand reasons; so he chooses not to notice them. Some fifty years ago, during our first years at university, Luis Prieto and I circulated within a network of cosmopolitan groups dominated, sometimes in excess, by eccentricity; many of them were Europeans who came to Mexico during the war, who found here the promised land and did not return to their countries of origin. We moved among them with remarkable ease. When an unrepentant sane person fell into those spaces, a close relative, for example, who was visiting from abroad, a mother, a brother, whom it was impossible to not host or entertain, that sane person in a sane person’s clothing became unbearable; even to those of us who were not part of that brotherhood, but were merely fellow travelers, his presence in that environment seemed insane, but despite this, one made all the necessary concessions, the same ones that they, the sanest of the sane, would do when they are generous and well mannered for someone with a mental problem. Of all the places I have lived, only in Warsaw, but especially in Moscow, was I able to become part of those enchanted spaces, those hives of “innocents” where reason and common sense wane and an “odd” temperament or mild dementia may be the best barrier to defend oneself against the brutality of the world. The mere presence of the eccentric creates an uneasiness in those who are not; I have sometimes thought that they detect it and that it pleases them.

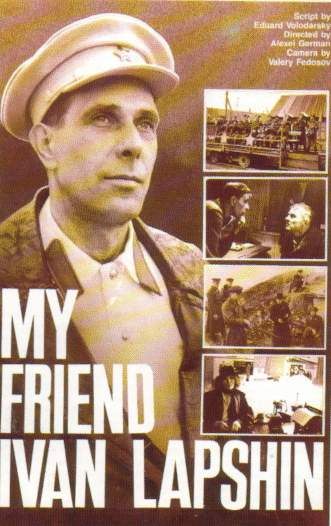

They are second-rate “oddballs.” My stays in those cities considered difficult by most of the world were for me welcome refuges of unspeakable happiness, always conducive to writing… Everything surprises me here. Is it possible that the time has arrived in which the truth is beginning to break through—or is it another illusion? I think it wouldn’t be bad at all to spend a long while in Moscow, within the next four or five years, if by then this phenomenon takes off and senescence hasn’t gotten the best of me. I have breakfast with my friend Kyrim. He summarizes the Congress of Filmmakers, which took place last week: the Association’s leadership was replaced completely. It has been an explosion of national proportions. None of the dinosaurs of the old guard remained in their posts, including some extremely powerful and prominent figures from a professional point of view like Sergei Bondarchuk, director of War and Peace, a true classic of contemporary Russian cinema. He lost his job due to his sectarianism, his contempt for the trends of young people and contemporary forms, and for trying to keep alive that abhorrent maxim coined by Siqueiros, no less: “Ours is the only path.” I understood better the concerns of my seat mate from the plane; if what happened here occurred in Prague, the film studios would be closed and she would be discharged from her post. No more festivals in San Sebastian or Latin America! The tropical men, the mulattos, their spectacular pricks would disappear from her fantasies, and she would be constrained to local experiences. I should have started this entry with Kyrim Kostakovski, a mathematician, but fundamentally a man of the cinema. He was at the National Film School of Lodz at the same time as Juan Manuel Torres, and was married to a Mexican, one of my best friends. Years ago, I traveled with them to Tashkent, Bukhara, and few stories of mine I like about that trip. 2 We had not seen each other for five or six years, but from the first moment, we began to talk like always, as if no time had passed. As with all my Russian friends, I would discuss with Kyrim film, literature, opera, people, and, of course, politics, until the wee hours of the morning. I often decided that I was no longer going to tolerate his irascible out- bursts. Our dialogues resembled those of Naphta and Settembrini: each of us began to defend a play, a literary movement, a type of cinema—Bergman’s, Fellini’s, Clair’s, or Pabst’s—and the other would insult it until late into the night and with wracked nerves each of us would end up defending the position that he had previously attacked and refuting what he had originally defended. In other words, arguing, whether for hours or days, is a Russian sport. Kyrim’s passion for Gogol, vast and unfailing, is perhaps what most unites us. Over the years and distance our dialogue has become much less strident. After recounting to me the circumstances of the film conference, he told me that he had accompanied Viktor Shklovsky to England.The University of Essex had awarded him an honorary doctorate. After the ceremony they returned to London, where they had been booked in a rather mediocre hotel. No expense had been spared on the public events, banquets, social activities, etc., but when it came to lodging the British really cut corners. They had planned to visit to the British Museum in the afternoon. The writer was about to leave his minuscule cubicle when, after making a sudden movement to open a door, an armoire fell on him. He rolled to the floor under the cabinet; the blow caused him to lose consciousness. A doctor arrived, applied iodine and arnica, gave him an injection and, with considerable trouble, managed to get him into bed. Shklovsky is a man of eighty five, if not older. Kyrim thought that because of his age he might not survive the blow. Devastated, he returned to his room to rest a moment, waiting for another doctor to arrive, a specialist who had been called. Half an hour later, he heard the phone; he feared that it was the hotel manager or the new doctor with bad news. But no, it was Shklovsky himself, ready to head to the museum. They spent the rest of the day there, touring its many rooms, seeing everything, collecting data, taking notes, theorizing. Only on the plane back to Moscow did he begin to complain of discomfort, and he showed Kyrim his purple-blue swollen ankles. Kyrim’s grandfather met Shklovsky in his youth, back in the twenties. He was a mathematician and supporter of the October Revolution. In 1937, uniformed men came to their house and took him away; shortly thereafter, three of his sons were kidnapped. They were Jews and Trotskyists—therefore, enemies of the revolution, agents at the service of foreign espionage. Kyrim’s father was the only survivor, having been at the time barely a child. In 1957 the honor of the entire family was vindicated, but none of them returned from Siberia alive. He and his family have been rather skeptical. But this time Kyrim is excited about what is happening in the country, especially in film, and tells me that wonderful films have been made and about what is on the horizon: Abuladze and Paradzhanov in Georgia, he says, are fabulous, and he tells me about a Russian film by Gelman, in his opinion the best in the history of Soviet cinema:  My Friend Ivan Lapshin, “A very sad film, the farewell to an epic, a sentimental story about all the wretched generations who have lived in Russia in this century. ”Try to see it here, he says, because in Prague you will for sure never be able to. The public, of course, is divided; the intelligentsia, students, scientists are all in favor of this kind of cinema, but we are a country of masses, immense masses manipulated from above, guided by emotion, and they will undoubtedly think it’s an insult to our history. In the afternoon I gave my lecture at the Library of Foreign Languages: “Fernández de Lizardi and The Mangy Parrot, the First Mexican Novel. ”A small audience, a handful of Hispano-Americanists, mostly friends or acquaintances from my previous stay; one of them, in a very fraught Spanish, paid me very nice compliments in his introduction, but said he was glad to see me again in a Moscow freed from the defects that caused me so much pain in the past. Who knows what he meant! After the reading had begun, the door opened noisily, and a woman of an advanced but difficult to discern age, tall, stout, dressed elegantly in black, marched in and sat on the front row, directly in front of me. She listened to me with indifference, like a Roman matron who for some unknown reason had to endure a reading by one of her slaves. And so she remained throughout the whole lecture: haughty, histrionic, commanding attention, except at the end, when I read a scatological fragment that I introduced as an example of a language that broke ties with the legal and ecclesiastical language used until then in books. An effort to find the language appropriate to the circumstances of the new nation. This episode takes place in a disreputable gambling house where the protagonist seeks shelter for the night:

My Friend Ivan Lapshin, “A very sad film, the farewell to an epic, a sentimental story about all the wretched generations who have lived in Russia in this century. ”Try to see it here, he says, because in Prague you will for sure never be able to. The public, of course, is divided; the intelligentsia, students, scientists are all in favor of this kind of cinema, but we are a country of masses, immense masses manipulated from above, guided by emotion, and they will undoubtedly think it’s an insult to our history. In the afternoon I gave my lecture at the Library of Foreign Languages: “Fernández de Lizardi and The Mangy Parrot, the First Mexican Novel. ”A small audience, a handful of Hispano-Americanists, mostly friends or acquaintances from my previous stay; one of them, in a very fraught Spanish, paid me very nice compliments in his introduction, but said he was glad to see me again in a Moscow freed from the defects that caused me so much pain in the past. Who knows what he meant! After the reading had begun, the door opened noisily, and a woman of an advanced but difficult to discern age, tall, stout, dressed elegantly in black, marched in and sat on the front row, directly in front of me. She listened to me with indifference, like a Roman matron who for some unknown reason had to endure a reading by one of her slaves. And so she remained throughout the whole lecture: haughty, histrionic, commanding attention, except at the end, when I read a scatological fragment that I introduced as an example of a language that broke ties with the legal and ecclesiastical language used until then in books. An effort to find the language appropriate to the circumstances of the new nation. This episode takes place in a disreputable gambling house where the protagonist seeks shelter for the night:

Four or five other wretches, all in the buff and, as far as I could see, half drunk, sprawled like pigs over the bench, table, and floor of the pool room.

Since the room was small, and our companions the sort of people who eat cold, dirty food for supper and who drink pulque and chinguirito, they were producing an ear-shatter- ing salvo whose pestilent echoes, finding no other outlet, came to rest in my poor nostrils, thus giving me in one instant such a migraine that I could not bear it, and my stomach, unable to withstand the fragrant scents, heaved up everything I had eaten just a few hours earlier.

The noise that my evacuating stomach made woke up one of the léperos there, and as soon as he saw us, he started to spew a blue streak of abuse out of his devilish mouth.

“You raggedy sons of bitches…!” he said.“Why don’t you go home and vomit on your mamas, if you’re already so drunk, and not come here to rob people of their sleep at this time of night?”

Januario signaled to me to keep my mouth shut, and we lay down on the billiard table; and between its hard planks, my migraine, the fear instilled in me by these naked men whom I charitably judged to be merely thieves, the countless lice in the blankets, the rats that ambled over me, a rooster that spread its wings from time to time,

the snores of the sleepers, the sneezes that their backsides produced, and the aromatic stench that resulted, I spent the most miserable night.

The woman on the front row lost her stone like expression. When I referred to “the snores of the sleepers, the sneezes that their backsides produced, and the aromatic stench that resulted,” she shouted, filled with passion, “That, gentlemen, is the Mexico that I love!” And then when I asked if anyone wanted to ask a question or make a comment, she was the first to speak.“Coincidence of coincidences!” she said. “I came to the library to find some pamphlets written by my husband, Adam Karapetian, the anthropologist, deceased now unfortunately for twenty-five years in Medellín, Colombia, where I live, Armenian by birth, of course, as the surname implies. They are all studies about your country, inspired under the stars, written first in 1908 and again in 1924. On the latter date I accompanied him to the jungle. I was about to leave the library just now when I saw the announcement for a lecture on Mexico, yours, maestro. If my husband were alive he would have stood up to embrace you, because you both work along the same lines I can tell. I’m looking for those opuscules, some very difficult to find, they don’t have them in this library, but I am sure I’ll find them where I least expect it. The most important one concerns a feast in the tropics, a religious feast with a pagan end. Karapetian was only interested in the feast as an anthropological topic, the feast in Mexico, Bahía, Puglia, New Guinea, Anatolia. The one that most interested him was one in the middle of the Mexican jungle in honor of a holy shitting child. (Laughter.) No, one mustn’t be afraid of words, what one must consider is in what circumstances the feast was celebrated. I was there, I saw it all! The blazing sun and the land transformed into shit! It took twenty days for my nose to lose that stench!” And then she got up, put a card in my hand and left the auditorium with an air of extreme dignity. As the door closed we all broke out into laughter. The card read: Marietta Karapetian, and below the name the inscription: Fine Hand Painted China and, then, another line in tiny, almost illegible print read: I apply leeches. Hygiene and discretion guaranteed. Who knows what that could be! I still haven’t met the translator of my novel Juegos florales [Floral Games]. I was hoping to talk to her after the conference, but she didn’t introduce herself. I’d love to walk around for a while, but I’m afraid of the dampness. I wouldn’t want to wake up with another cold tomorrow.Tonight I’ll finish Michael Strogoff, and then go to bed.

20 May is an excerpt from the book The Journey by Sergio Pitol published by Deep Vellum Publishing.

It was translated by George Henson

Sergio Pitol Demeneghi (born 18 March 1933 in Puebla) is a prominent Mexican writer, translator and diplomat. In 2005 he received the Cervantes Prize, the most prestigious literary award in the Spanish-speaking world.

Sergio Pitol Demeneghi (born 18 March 1933 in Puebla) is a prominent Mexican writer, translator and diplomat. In 2005 he received the Cervantes Prize, the most prestigious literary award in the Spanish-speaking world.

Posted: June 29, 2015 at 6:00 am