The Words Flow

John Pluecker

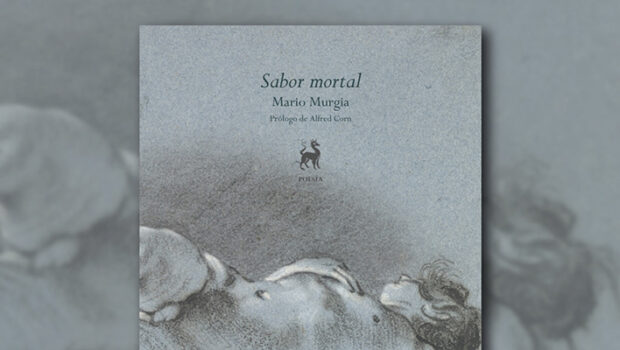

César Aira,

César Aira,

Ghosts,

New Directions, New York, 2008.

Translated by Chris Andrews

From the first minute I held César Aira’s Ghosts in my hand, I was pleased. The cover with its soft shadow darkening from bottom to top. Its mysterious raised dot of white at the center and raised lettering at the base. The sparse design of the book drew me in. Also its size. Its smallness. The first few pages are engrossing: Aira quickly drops the reader into a whirlwind of activity in a condominium tower under construction in Buenos Aires.; builders, engineers, decorators, architects busily prepare the tower for its future residents, who coincidentally are touring their soon-to-be home that very day. Their children run excitedly through the shell of the building. After some time with these busy, frantic, wealthy people, they leave and we are left in the building with a Chilean family, the family of the watchman who lives at the site. Their children continue to play: the thought of children playing on these unembellished concrete floors, these vast planes with no walls to contain them produces a tension that lasts until the final sentence of the book. What prevents them from falling?

We enter the final day of the year with the Viñas family, shopping, playing, working, napping, eating, drinking. All the while, dusty, naked male ghosts wander though the building, floating around aimlessly, unworthy of note or explanation. The joy of reading this book (and Aira in general) is his uncanny ability to weave anecdotal (often bizarre) twists of story-telling into a whole that is resolutely experimental and destabilizing. The careful prose of the book speeds along gently with nary a wasted word or cliché. The prose feels limber, flexible; it bends and stretches. The words are never heavy or plodding. (No doubt, the masterful translation of Bolaño translator Chris Andrews is to thank here.) The words flow, reflecting la huida hacia adelante, the flight forward, that Aira has mentioned in interviews. Aira is iconoclastic. In interviews, he has insisted he does not edit or plan the structure of his novels before writing. He is more interested in the process of writing, the commitment to artistic creation than a final product. He writes a page a day and ends up published two or three of these small novels each year, mainly with small presses in Argentina.

In the midst of this continuous flow of story, Aira includes a number of long philosophical, sociological and architectural refl ections on life, man, art, building and form narrated in the voice of a teenage girl, Patri Viñas. Aira delights in what is seemingly (though actually not) tangential; he clearly loves the reflective mode. He leisurely explores theory and the deep complexity of artmaking with a language and a complexity of thought seemingly foreign to this teenager who becomes the axis for the second half of the book. In one of these unconstrained soliloquies in the voice of Patri, Aira reflects on the wisdom of the seemingly ignorant, the philosophical depth of the apparently uneducated: “A person might have never thought at all, might have lived as a quivering bundle of futile momentary passions, and yet at any moment, just like that, ideas as subtle as any that have occurred to the great philosophers might dawn on him or her.” Aira is obsessed with these moments and with writing these moments in a nimble prose that moves continuously on from one scene, from one thought to the next.

The building where the Viñas family lives is empty, a shell. The structure of the novel (and its actual design as a book) seems similarly shell-like–well designed, masterfully constructed, perplexing. The structure with no artificial boundaries or great adornment is actually more exciting, more loaded with potential than something finished, fully decorated and fleshed out. These half-finished structures become spaces of play and diversion, eliciting and allowing a sense of freedom a finished structure could never provide. In the end, this unfinished world inhabited by an immigrant family and a legion of ghosts becomes a stage for a singular tragedy. Who are these naked male ghosts? Who is this happy family celebrating New Year’s Eve, unconcerned with the ghosts around them? Who is Patri and why is she increasingly obsessed with these ghosts? Aira never answers these questions. He is not interested in explaining. Hopefully though, at the book’s end, you, like me, will be so entranced by the story that this freedom, this unfinishedness, this lack of fixity only adds to its sad joy.

Posted: April 18, 2012 at 9:28 pm