The Future of Power

El futuro del poder

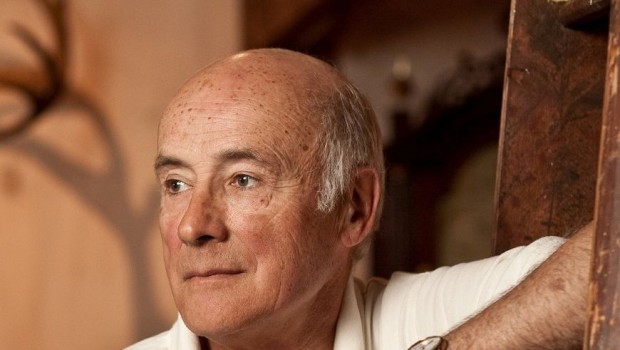

Joseph Nye Jr.

Joseph Nye Jr. is a Distinguished Service Professor and former Dean of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He coined the term soft power in the late 1980’s. The term first came into widespread usage following a piece he wrote in Foreign Policy in the early 1990s. He has published many works in recent years, the most recent being The Future of Power (2011). This time he talks about the Middle East, the Wikileaks Phenomenon and soft power.

© Universidad de California, Bekeley

* * *

The Three-Dimensional Chess Game

Power always depends on context. Power is the ability to affect others to get what you want, and you can do it with threats or coercion, payments, or you can do it with attraction or persuasion. That is what I call soft power. What is interesting is that what produces power, whether or not we jet what we want, depends on the context. If we think of a power today of having three very different contexts like a three-dimensional chessboard, then the top chessboard would be military relation between states. The United States is the only superpower. It is the only country with the ability to project military power globally, and it is probably going to stay that way for a couple of decades. Go to the second level, which consists of economic relations between countries, and we will find that it is multifaceted. This is where Europe acts as one, and when it does, its economy is bigger than the American economy. China, Japan and others also play an important role. Go to the bottom board of this three-dimensional game, transnational relations–, things that are crossing borders outside the control of governments–and you find power is chaotically distributed amongst bankers, terrorists, etc. To call this unipolarity or multipolarity is a categorical mistake. You are taking ideas that are on one board and applying them on another board where they don’t matter. It also means that if we are trying to make changes that are on this bottom board, we can not do it by ourselves. We have to get others to work with us. We can only manage these non-governmental/ transnational processes if we have cooperation of other governments. That is where soft power comes in. We need to be able to organize networks, create institutions, and persuade others to join in common endeavors.

Three Ways of Thinking About Power

Sometimes people call it the three faces of power. When Robert Dahl wrote his very important book on power in the late ‘50s, he said power is the ability to get others to do what they otherwise would not do. That is a good definition of power in some circumstances. If I could make you do what you otherwise would not do, then I have power over you. But Bachrach and Baratz, who were political scientists who wrote in the early ‘60s, thought that Dahl was missing something. “Suppose that I can set the agenda so that your issue never comes up in the first place. Then, I do not have to get you to do what you otherwise would not do. That is another form of power”. They called that the second phase of power. Then a little later in the ‘70s, Steven Lukes, a sociologist proposed a new idea; which is not whether I can just twist your arm or set the agenda so I can exclude your issue, but suppose I can influence you to set your preferences; make you want what I want. That third phase of power, which Lukes introduced, is about the establishment of preferences. All three of these are dimensions of power. Not one is right or wrong…

On Soft Power

Soft power is the ability to get the outcomes you want without the coercion or payment. Essentially it’s through agenda-setting attraction or persuasion. I came upon this thought when I was writing a book called Bound to Lead 20 years ago. At that time, there was a great belief that America was in decline. My friend and colleague, Paul Kennedy, wrote a book called The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers saying the United States was going the way of Philip II of Spain or Edwardian England. I did not think this was right, and I was writing a book to say why I didn’t agree with him. As I was thinking about it, I looked through instances of American hard military power and economic power. There was still something missing: the ability of Americans to get what they want through attraction, persuasion, and setting the agenda. That led me to develop this idea of soft power. It’s an important part of our foreign policy, but when we talk only in the old fashioned terms of basically twisting arms, we miss the crucial role that it plays in our foreign policy.

Soft power is hard to get your hands on in some ways, but it is also worth to remember that hard power is illusory as well. If I have 10,000 battle tanks and you have 1,000 battle tanks, there is a tendency for us to think that I am ten times stronger. If we are fighting in the desert, that may be true. However, if we are fighting in a swamp, I may not get the outcomes I want, as the Americans found in Vietnam. Therefore, we should not assume that hard power or military power is so easily measurable either. Power always depends on the context. Soft power often grows out of a country’s culture if the culture is attractive to others, its values when they actually live up to those values and policies when its policies are seen as legitimate in the eyes of others. That is a little more ephemeral. It is not something that we can drop on our foot or on a city–that is sometimes called the concrete fallacy that power is only something concrete. Soft power may often have a more intangible aspect to it, but not only that. If you have a successful military, it can produce hard power by winning victories; but it also can produce soft power. For example, in the Indonesian tsunami case in 2004, the U.S. Navy delivered tsunami relief to Indonesia, which made a big impact on the standing of the United States in the world. If you want a concrete set of numbers on that, in the year 2000, three quarters of the citizens of the largest Muslim country in the world, Indonesia, had a positive view of the U.S. After the invasion of Iraq in May of 2003, that went down to 15%. After we helped using the military to provide relief to the Indonesians after the tsunami, it went back up to about 40%.

Evolution of the International Affairs

In 2002, I gave a lecture to a group of generals at an army conference. I talked to them about the importance of soft power. Later in the conference, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld appeared and one of the generals asked him what he thought of soft power. His reply was, as reported in the Financial Times, “I don’t understand it.” That had a cost in terms of policy. For example, when he wanted to send the 4th Infantry Division across Turkey to invade Iraq from the north, we had lost our soft power in Turkey by lacking legitimacy from a second U.N. resolution. The Turkish Parliament said “no”, and we had to send the 4th Infantry Division down through the canal and up through the gulf, and they were late to the war. That is a case where failure to understand soft power undercut our hard power. Contrast that with his successor, Robert Gates, who in 2007 gave a speech in Kansas City in which he said, we need to spend more on soft power. He said there are just too many things today, which the Pentagon cannot solve by itself. We need a partner. He said “I’m here to plead with you for more resources for the State Department”. You may think it is strange to have the head of the Pentagon to have to ask for resources for the State Department, but that is the nature of the world is today.

The Decline of The U.S. And The Rise of China

Power transition is a shift of power among states. Power diffusion, however, which is the shift of power away from governments and states to non-state actors, is more of a novel or unfamiliar territory. However, power transition still matters. The trouble is that the narrative we use to explain it is the traditional narrative where there is a hegemony in a rising state, the hegemony declines the rising state overcoming it, this creates fear and eventually creates war. That is a very familiar narrative in the literature on political science in international politics. It goes all the way back to Thucydides. He asked why was it that the Greek city-state system tore itself apart in the 5th Century BC. It was the rise and the power of Athens and the fear it created in Sparta. World War I is often attributed to the rise and power of Germany and the fear that created in Britain. There are some analysts today who say this will be the story of the 21st Century; the rise and power of China and the fear it will create in the U.S. leading to a great conflict. I think it’s not right and it’s bad history. It’s bad history because Germany had surpassed Britain in overall economic strength in 1900, and I don’t think China is about to surpass the United States for decades. That gives us more time to arrange a better transition than we have seen in other times in history and it means we have to be less fearful.

The word “decline” can be a fuzzy word. It can mean absolute decline or relative decline. Absolute decline would be something like the fall of Rome, which people often refer to. But Rome was an agriculture economy which was stagnant. There was no productivity, it had no economic growth, and it was torn by internecine warfare. That led to decay internally, and absolute decline. I do not think the United States is in that situation. We have major problems with our budget deficit, our debt and with improving our education, but we’re, as the World Economic Forum shows, the fourth-most competitive economy in the world after Switzerland, Sweden, and Singapore. China, incidentally, is 27th. In that sense, we’re also an economy which is at the forefront of new technologies: nanotechnology, biotechnology, Web 3.0, etc. We have some of the best universities, the best R&D and the best entrepreneurial culture; this is not absolute decline. On the other hand, if we look at other countries, and not just China, but India, Brazil, and others are getting closer to us. Will they reduce the gap between the United States and these other countries? Sometimes it is called “the rise of the rest”. We can portray that as relative decline because the gap is smaller, but the rise of the rest is a better way to put it because even as the others get closer, the U.S. may still remain as the most powerful country–which I happen to think it will. It is important not to mix up absolute decline and relative decline; and it is even better not to express it as relative decline, but as the rise of the rest. Consequently we need new strategies for us to deal with that type of position.

Transition

The traditional theories about hegemony put too much stress on who is number one. They are not all that good historically. The period after 1945, the Americans had a nuclear monopoly and about half the world’s product. Even in that context, we could not stop the “loss of China”, we could not win the Korean War and a little later we could not win the Vietnam War. It is clear that hegemony does not explain very much. I think the problem, though, is hegemony conveys the image that “we’re king of the mountain” and “we give orders”. I think what we are seeing in the 21st Century in the information age is that the image is better expressed not as hegemony or king of the mountain, but being in the center of a circle and you have to attract others to you, to work with you in order to deal with these problems. That is why I think this old narrative of hegemony and decline gets in our way. Instead of asking “are we slipping down the mountain?” or “is someone creeping up the mountain closer to us?” we should ask “are we attracting others in this circle using our soft power, using our capacity to develop networks and institutions?” That is the right way to think about power in this setting.

The Importance of the Diffusion of Power

If we ask what is happening in the world today, the reduction in the costs of computing and communication has just made information so plentiful that it has changed the structure of who can do what. I used the analogy of cars in the book to demonstrate how the cost of computing power has declined a thousand-fold in the last quarter of the XXth Century. If the price of a car declined that rapidly, you could buy a car today for five dollars. If anything becomes that cheap, the barriers for entry are reduced and everybody can get into the game. In 1975, if you wanted to communicate between San Francisco, Johannesburg, Moscow and Beijing simultaneously, you could do it, but it would be expensive. You needed to be a government or a large corporation. Today, anybody can do that for free with Skype. This is just a very big change. It is not that governments are out of the picture and it is not that governments are not the most powerful actors on the stage, it is just that the stage is a lot more crowded. That means you are going to have to rethink how you’re going to exercise your power when you’re dealing on a very crowded stage with information-empowered actors, who previously were priced out of the market.

Cyber Domain

There are two mistakes you can make thinking about power in the cyber domain. One is to assume that governments aren’t the most important figure, and the other is to assume that governments can do everything. If you take that latter view, you might strive for cyber superiority. It makes sense militarily, for example, to think of naval superiority. Sure, there are pirates and so forth, but the U.S. Navy has superiority in naval matters. In the cyber domain, it does not make sense to talk about cyber superiority or to be able to dominate cyberspace because we do not have enough control over pirates or other players. But the opposite mistake is people who say that in the cyber domain, everybody is equal. They are not. There is a wonderful New Yorker cartoon from the ‘90s that depicts one dog sitting at a computer talking to another dog and the first dog says to the other one, “Do not worry. On the Internet, no one knows that you are a dog.” That is quite a prescient cartoon because it means if you are attacked in cyberspace, you do not know whether the attack came from a hacker, a criminal, a terrorist group or from another state. And they may, if they are clever, route it in such a way that you think it is one of the others. Some people have said that means it is all equal. Well, no it’s not. Not all dogs are equal. Some are bigger, bite harder and have more resources.

Social Media and Egypt

It really is a fascinating case. The conventional wisdom about Egypt used to be that you had no choice: you either had to support Mubarak the autocrat or you wound up with the religious fanatics of the Muslim Brotherhood. There was no middle ground. This enormous burgeoning of information over the last twenty or thirty years has created a new middle ground and those are the people we saw in Tahrir Square. Not only did it create this movement, it solved the problems of coordination and collective action by using Twitter and Facebook to coordinate themselves. That is a very different type of politics. It’s not the whole story of the politics–the army still plays a crucial role. If the army had decided to shoot, as in places like Libya or Yemen, it might have had a different outcome–Tiananmen Square and Iran are cases where armies did use force. But in Egypt the army held back. They essentially had hard power, but the Tahrir Square demonstrators had the soft power of the narrative. Now what you’re seeing is a bargaining between these two forces. We are in act one of a long play. We do not know how it is going to turn out, but it is interesting that it is very different from the dramas we thought of ten years ago when there were only the autocrats on one hand and the Muslim Brotherhood on the other.

Institution-Building in a Place Like Egypt

That is going to be a crucial question to see what act two of this play is going to look like. Will the people who were so good at using social media in coordinating opposition be able to use those and other techniques to create political parties? Elections are now scheduled to be held after the constitutional referendum in Egypt, but if they’re held too soon this new group won’t have built up the institutional capacity. One of the interesting questions of the next steps in Egypt is will they have enough time and skill to develop the institutions that make democracy really work. Democracy is more than elections–democracy is not electocracy, it is having a civil society with institutions that can express different views in a peaceful way.

Navigating That Transition

It is going to make foreign policy a lot harder in the global information age. In foreign policy, you have to reconcile different interests to get as many of them as you can. Obama clearly had interests in dealing with the Egyptian government; the possessors of hard power. We wanted to keep the peace treaty with Israel and the peace process intact. We also wanted Egyptians to help balance Iranian power. At the same time we, as it is our foreign policy, wanted to appeal to these younger generations in Tahrir Square, and that’s where the narrative and soft power come in. Focusing just on Mubarak would have produced short-run stability but long-run instability. For the long run you needed a narrative that would appeal to this next generation. Trying to traverse that chasm is like walking on a tight rope. The administration wobbled on that tight rope risking tipping one way or the other prematurely, but by and large they crossed it. I would say they crossed it successfully, and that was a smart exercise of power.

The WikiLeaks Phenomena

The ability to steal state secrets is as old as human history. But in the past, you sent a spy somewhere and he/she carried out a briefcase full of documents or State Department cables. Now you have 250,000 State Department cables from all around the world exfiltrated on a Lady Gaga disc and it was instantly spread around the world. That is very different. We have spent an awful lot of our time assuming that WikiLeaks, the organization, or Julian Assange, the individual, is the problem. Basically, Assange and WikiLeaks are a symptom, not a cause. If Assange had never been born, something like this would have happened anyway. What we should be doing is directing our attention not at finding grounds for prosecuting Assange on the theory that he was in possession of stolen property–after all, so were the major newspapers–but on better monitoring of our databases.

The Evolving Situation in Libya

Humanitarian interventions are dangerous because you may start with good intentions, but you may end up with inadvertent consequences that may be opposite to your intentions. It is important as you go in to a humanitarian intervention to be quite specific about what you are doing. It looked like Gaddafiwas going to slaughter civilians in Benghazi and that the United States, as signatories to the U.N. resolution on the responsibility to protect the lives of innocent civilians, had some obligation. People say it was not a vital interest. True, humanitarian interests may not be vital, but they are important. In that sense, Obama was right to recognize it, but he was also right to wait until he had the soft power of legitimacy that was created by the Arab League resolution and the U.N. Security Council resolution. Further, he said there would be no American boots on the ground and the Americans were not necessarily taking the lead–they were there for a limited duration. Those strike me as smart ways to try to put boundaries to the problem so that you do not go in with a good motive and wind up with a mess. Somalia would be a good example where we went in to provide humanitarian relief, and wound up with Black Hawk Down. Libya might be divided between an east and west, it may be prolonged, but I think the way Obama has tried to contain the problem in his initial reactions is an exercise in smart power.

Joseph Nye Jr. es profesor distinguido y antiguo director del Kennedy School of Government en la Universidad de Harvard. Fue él quien acuñó el término soft power al finalizar la década de los ochenta, pero el uso de este concepto se extendió sólo a partir de un texto escrito por Nye en los años noventa para el Foreign Policy. Ha publicado muchos libros sobre política internacional, el más reciente es El futuro del poder (2011). En las siguientes páginas habla sobre el Medio Oriente, el fenómeno de Wikileaks y la incidencia del soft power en un mundo con nuevas reglas.

© Universidad de California, Bekeley

* * *

Un juego de ajedrez tridimencional

El poder siempre depende del contexto. Es la capacidad de influir en los demás para conseguir lo que uno quiere. Podemos hacerlo con amenazas y palos (coacción) u otorgando recompensas (zanahorias); también, recurriendo a la persuasión. A esto he llamado en otro lugar soft power. Lo interesante, en efecto, es que hoy las posibilidades del poder dependen de contextos heterogéneos. Como en un ajedrez tridimensional, la parte superior del tablero corresponde a las relaciones militares entre los países. EE.UU. es la única superpotencia con capacidad de proyectar su fuerza militar a nivel mundial. (Y probablemente continuará así durante un par de décadas más). En el escenario intermedio se encuentran las relaciones económicas entre los Estados de un mundo global. Europa actúa aquí en bloque –y cuando lo hace su economía es más grande que la estadounidense. China, Japón y otros países juegan también un papel determinante. Por lo mismo, el segundo escenario implica múltiples foros. Finalmente, en la base de este juego se encuentran las relaciones internacionales, donde el poder se encuentra distribuido caóticamente. Hoy en día las fronteras se cruzan (por banqueros, terroristas, etc.) fuera del control de los gobiernos. Llamar a esto unipolaridad o multipolaridad es un error. Estamos tomando las ideas de una de las dimensiones del tablero para aplicarlas en otras donde carecen de importancia. Ahora bien, si tratamos de realizar cambios en la base no podemos hacerlo solos. Tenemos que conseguir que los demás trabajen con nosotros. Podremos intervenir en estos procesos esencialmente no gubernamentales y transnacionales si contamos con la cooperación de otros gobiernos. Ahí es donde el soft power entra en juego. Hay que ser capaces de organizar redes, crear instituciones y persuadir a otros para unirse en objetivos comunes.

Tres formas de pensar el poder

En la historia de las ciencias sociales se ha hablado de los tres rostros del poder. Robert Dahl, quien escribió un libro importante sobre el tema a finales de los años cincuenta, afirmaba que el poder es la capacidad de lograr que otros hagan lo que de otra manera no harían. Una buena definición de poder en algunas circunstancias… Sin embargo, Bachrach y Baratz, dos científicos políticos de los años sesenta, advertían: “Supongamos que puedo fijar los asuntos a tratar de tal modo que tu problema no tenga relevancia. Por consiguiente, no hay posibilidad de que hagas lo que de otra forma no harías”. Se trata de otra forma de poder en su segunda fase. En los años setenta el sociólogo Steven Lukes señaló algo más: no es tanto que uno pueda coercionar o fijar la agenda, pero supongo que sí se puede influir para que alguien defina sus preferencias. Usted quiere lo que yo quiero. Esta tercera fase del poder introducido por Lukes actúa, en efecto, sobre la formación de nuestras preferencias. Tales son las tres dimensiones del poder y ninguna es correcta o incorrecta en sí misma…

Sobre el soft power

Soft power significa la capacidad de obtener resultados favorables sin coerción ni recompensa. Esencialmente, mediante una agenda de persuasión. Este es el argumento de mi libro Bound to Lead escrito hace 20 años. En ese entonces existía una fuerte creencia en torno al declive de Estados Unidos. Mi amigo y colega Paul Kennedy escribió The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, donde afirmó que EE.UU. estaba siguiendo los pasos de Felipe II de España o de la Inglaterra eduardiana. Según mi apreciación, esto no estaba bien; es más, ya estaba escribiendo un libro para exponer por qué no pensaba lo mismo. Al considerar el poder militar (hard power) y el poder económico norteamericanos, creí que debíamos tomar en cuenta aún esa capacidad de los estadounidenses para conseguir lo que quieren, digamos, mediante la atracción, la persuasión y el establecimiento de agendas. Eso me llevó a desarrollar la idea del soft power. Cuando hablamos en términos anticuados de armas, no se toma en cuenta el papel crucial que este poder desempeña en nuestra política exterior.

Hacerse de un soft power efectivo es difícil, aunque debemos recordar que el hard power puede ser ilusorio también. Si cuento con 10.000 carros de combate y el otro con 1.000, hay razones para pensar que soy diez veces más fuerte. Esto si nos encontramos en el desierto, pero si luchamos en un pantano no obtendremos los mismos resultados, como sucedió en Vietnam. Por lo mismo, no deberíamos asumir que el hard power militar sea tan fácil de medir. El poder siempre depende del contexto. El soft power a menudo surge de la cultura de un país si su práctica es atractiva para los demás, si se es coherente con los valores propios y nuestra política resulta legítima. Y aunque nunca es algo que pueda caernos sobre el pie, el poder es siempre concreto. No obstante, el soft power a menudo puede tener un aspecto más bien intangible. Una acción militar produce el hard power y también puede crear un soft power. Ejemplo: en el caso del tsunami de Indonesia en 2004 la Marina de los EE.UU. entregó ayuda a las víctimas y esto tuvo un fuerte impacto en la posición de los Estados Unidos. En el año 2000 en Indonesia –el mayor país musulmán del mundo– tres cuartas partes de la población tenía una visión positiva de los EE.UU. Sin embargo, tras la invasión a Irak en mayo de 2003, tal percepción bajó al 15%. Por su parte, tras la ayuda por el tsunami ascendió a cerca del 40%.

Evolución de las relaciones internacionales

En 2002 di una conferencia a un grupo de generales en donde hablé sobre la importancia del soft power. Más tarde hizo su aparición el secretario Donald Rumsfeld y uno de estos generales le preguntó qué pensaba del soft power. Su respuesta –como se informó en el Financial Times– fue: “No lo entiendo”. Tal actitud tuvo un costo en términos políticos. Cuando quiso enviar a la 4ª División de Infantería a través de Turquía para invadir Irak desde el norte, nuestra legitimidad ya había decaído. En la segunda resolución de la ONU, el Parlamento de Turquía dijo “no”. Así, nos vimos obligados a enviar aquella 4ª División por el canal o el golfo. Y llegaron tarde. Al no “entender” el soft power podemos estar socabando nuestro hard power. Esto contrasta con su sucesor, Robert Gates, quien en 2007 pronunció un discurso en Kansas City en el que sugirió que debíamos invertir más en nuestro soft power. De igual modo, afirmó que el Pentágono ya no puede resolver muchas cosas por sí mismo. Necesitabamos un socio. “Estoy aquí, dijo, para buscar más recursos destinados al Departamento de Estado”. Parece extraño que el jefe del Pentágono pida recursos para dicho departamento, pero la naturaleza del mundo de hoy lo exige así.

La decadencia de Estados Unidos y el ascenso de China

La transición del poder implica un cambio de poder entre los Estados. Asimismo, la diseminación del poder es el desplazamiento del poder de los gobiernos y los Estados a los actores no estatales –algo más que un territorio nuevo y desconocido. Pero la transición sigue siendo importante. El problema es que la historia que utilizamos para explicar los acontecimientos es tradicional: a una potencia hegemónica le corresponde un Estado en ascenso. Dicho de otra manera, el declive de un Estado hegemónico y el ascenso de otro crea miedo y propicia la guerra. Se trata de un relato muy conocido en la ciencias políticas y en las relaciones internacionales. Un retorno total a Tucídides. Éste se preguntaba por qué en el siglo V a.C el modelo griego de ciudad-Estado se desplomó. El poder de Atenas enfrentaba al de Esparta. La Primera Guerra Mundial se atribuye al ascenso de Alemania y el miedo correspondiente de Gran Bretaña. Algunos analistas de la actualidad –mis colegas– afirman que en la historia del siglo XXI el poderío de China minará a los EE.UU. dando lugar a un gran conflicto. Me parece que esto es un error. En 1900 Alemania había rebasado económicamente a Gran Bretaña. En este contexto, no creo que China vaya a superar a Estados Unidos en varias décadas. Por lo mismo, contamos con tiempo para ser menos temerosos y organizar una mejor transición comparada con las que hemos visto en otros momentos de la historia.

La palabra “decadencia” es confusa. Puede significar disminución absoluta o relativa. Absoluta sería algo así como la “caída” de Roma, a la que la gente se refieren con frecuencia y que, por cierto, duró tres siglos. Pero Roma fue una economía agrícola que se estancó. No había productividad ni crecimiento económico y fue desgarrada por guerras internas. Esto la llevó al debilitamiento y a la decadencia absoluta posterior. No creo Estados Unidos esté en una situación similar. Enfrentamos grandes problemas (como el déficit presupuestario, la deuda y un sistema educativo que debemos mejorar) pero también somos –según el Foro Económico Mundial– la cuarta economía más competitiva después de Suiza, Suecia y Singapur. China ocupa el puesto 27. De igual modo, somos una economía a la vanguardia de las nuevas tecnologías: nanotecnología, biotecnología, Web 3.0. Poseemos también algunas de las mejores universidades, el mejor sistema de investigación y desarrollo y la mejor cultura empresarial. No hay disminución en términos absolutos. Ahora, países como la India, Brasil y otros (no sólo China) se nos acercan también. ¿Se va a reducir la brecha entre esos otros países y EE.UU.? Se trata del a veces llamado “surgimiento del resto”. Uno puede hablar de disminución relativa porque la brecha es menor, pero una mejor manera de presentarlo es decir que se trata del crecimiento de los demás. Y aun cuando los otros se nos acercan, EE.UU. permanece a la cabeza. En conclusión, es importante no confundir decadencia absoluta y disminución relativa. Mejor incluso es hablar del ascenso de los demás y, por lo mismo, de la necesidad de nuevas estrategias para enfrentar nuestra posición.

Transición

Las teorías tradicionales sobre hegemonía ponen demasiado énfasis en quién es el número uno. Y eso no es del todo correcto históricamente. Durante el periodo posterior a 1945 los norteamericanos tenían el monopolio nuclear y alrededor de la mitad del producto mundial. Aún así, no pudimos parar los “extravíos de China”, ganar la guerra de Corea ni –un poco más tarde– la de Vietnam. Es claro que la hegemonía no lo explica todo. El problema radica en la imagen de ésta como el “rey de la montaña” hecho para dar órdenes. Lo que estamos viendo en el siglo XXI, en la era de la información, es que la imagen que expresa mejor dicha hegemonía no es la del “rey de la montaña”, sino la de quien está en el centro de un círculo y busca atraer a los otros para trabajar y hacer frente a los problemas. Por eso creo que el relato histórico de la hegemonía y la decadencia ya obstaculizan nuestro camino. En lugar de preguntar: “¿estamos cayendo o alguien está ascendiendo y acercándose a nosotros”, uno debe preguntarse: “¿estamos atrayendo a otros en este círculo gracias a nuestro soft power, es decir, a nuestra capacidad para establecer redes e instituciones?” Esta es la forma correcta de pensar sobre el poder en una nueva configuración.

La importancia de la diseminación del poder

Si uno se pregunta qué está pasando en el mundo de hoy, veremos que la reducción en los costos por servicios de computación y comunicación han multiplicado la información de forma tan patente que ha cambiado la estructura de quién puede hacer qué. Estos precios se redujeron mil veces en el último cuarto del siglo XX de manera que si el costo de un coche hubiera descendido así de rápido, hoy podríamos comprar uno por cinco dólares. Cuando algo baja las barreras se reducen y todo el mundo puede entrar al juego. Si en 1975 uno hubiera querido comunicarse desde San Francisco a Johannesburgo, a Moscú y a Pekín al mismo tiempo, podía hacerlo pero a un precio muy alto. Se necesitaba ser un gobierno o una corporación grande. Hoy cualquiera puede y de forma gratuita con Skype. Este es sólo uno de los grandes cambios. Ahora bien, ello no implica que los gobiernos ya no aparezcan en la foto: es sólo que el nuevo escenario se encuentra mucho más lleno de gente. Significa que ahora vamos a tener que repensar –en tanto gobiernos– cómo ejercer el poder en una era muy concurrida y con agentes facultados para aquella información que antes estaba fuera del mercado.

Dominio cibernético

Hay dos errores al pensar sobre el poder en el plano cibernético. Uno es suponer que los gobiernos no son importantes, otro es asumir que pueden hacerlo todo. Si uno suscribe este último punto de vista podría querer luchar por la superioridad cibernética. Tiene sentido militar, por ejemplo, pensar en la superioridad naval. Claro, hay piratas y todo eso, pero la Marina de los EE.UU. tiene superioridad en asuntos navales. En el ámbito cibernético es absurdo hablar de superioridad al grado de querer dominar el ciberespacio ya que no contamos con suficiente control. El error opuesto lleva a la gente a afirmar que en el dominio cibernético todo mundo es igual. Y no es así. Un maravilloso cartón del New Yorker de los años 90 –donde un perro chatea con otro– decía: “No te preocupes. En internet nadie sabe que eres un perro”. Se trata de una caricatura profética porque si hoy te atacan desde el ciberespacio nunca sabrás si fue un hacker, un delincuente, un grupo terrorista u otro Estado. Y es posible, si son inteligentes, desviar la ruta de tal manera que uno piense que han sido otros. Para algunas personas esto significa igualdad. Pero no, no lo es… No todos los perros son iguales; algunos son más grandes, su mordida es más fuerte y tienen más recursos.

Las redes sociales en Egipto

Este es un caso realmente fascinante. La sabiduría convencional sobre Egipto solía suponer que no existía otra opción: apoyar a Mubarak el autócrata o a los fanáticos de la Hermandad Musulmana. No había término medio. Pero el enorme florecimiento de la información durante los pasados veinte o treinta años ha creado un nuevo entorno: son las personas que vimos en la plaza Tahrir. Y no sólo creó a estos individuos sino que resolvió sus problemas de coordinación y acción colectiva dándoles dispositivos como Twitter y Facebook. Estamos ante un tipo muy diferente de política –aunque no toda la política ya que el ejército sigue desempeñando un papel crucial. Si éste decidía disparar, como en Libia o Yemen, el resultado habría sido otro. Tiananmen e Irán son dos casos en que el ejército empleó la fuerza, pero en Egipto se detuvo. El hard power frente a los manifestantes de la plaza Tahrir, el soft power de esta historia. Lo que estamos viendo ahora es una negociación. No sabemos cómo va a terminar pero es interesante ver que se trata de algo muy diferente a las posibilidades de hace diez años, cuando sólo existía el autócrata y, por otro lado, la Hermandad Musulmana.

Fortalecimiento institucional en Egipto

Hay algo que va a ser determinante en el segundo acto de esta obra. ¿Las personas que han sido eficaces en el uso de las redes sociales podrán usar éstas y otras técnicas para crear partidos políticos? Las elecciones están programadas para después del referéndum constitucional, pero si se celebran tan pronto el grupo no habrá construido aún ninguna capacidad institucional. Así, una de las preguntas fundamentales para los próximos días en Egipto es si tendrán el tiempo necesario y la habilidad para desarrollar esas instituciones con las que la democracia funciona realmente. Porque la democracia es más que elecciones: no una electocracia sino una sociedad civil con instituciones que expresen puntos de vista diferentes y de manera pacífica.

Navegando hacia la transición

La política exterior se torna mucho más difícil en la era de la información. En política exterior hay que conciliar intereses diferentes para poder sacar adelante a la mayoría de ellos. Evidentemente, Obama estaba interesado en un trato con el gobierno egipcio, los poseedores del hard power. Deseábamos mantener el tratado con Israel y el proceso de paz intactos. Necesitábamos también a los egipcios para equilibrar el poder de Irán. Al mismo tiempo, nuestra política exterior deseaba un acercamiento a las generaciones jóvenes de la Plaza Tahrir. Es allí donde el soft power parece determinante. Apoyándonos sólo en Mubarak habríamos obtenido cierta estabilidad, pero no a largo plazo; para esto, se necesitaba la participación de aquella generación nueva. Si se quiere, fue como andar sobre una cuerda floja al tratar de atravesar el abismo. Creo, sí, que la administración titubeó sobre esa cuerda –con el riesgo de caer–, pero al final la cruzó. Y yo diría que con éxito: fue un ejercicio de poder inteligente.

El fenómeno WikiLeaks

La habilidad para robar secretos de Estado es tan antigua como la historia misma. En el pasado usted enviaba un espía a alguna parte y él o ella salía con un maletín lleno de documentos o cables del Departamento de Estado. Ahora usted tiene 250 mil cables de Departamentos de Estado de todo el mundo extraídos –creo que en un disco de Lady Gaga– y difundidos al instante por todo el mundo. Esto es muy diferente a lo que sucedía en el pasado. Ahora bien, ya hemos asumido durante mucho tiempo que Wikileaks (la organización) o Julián Assange (el individuo) son el problema. Pero básicamente, Assange y WikiLeaks son un síntoma, no una causa. Si Assange no nacía, de cualquier manera algo así habría ocurrido. Lo que debemos hacer es no malgastar nuestra atención buscando motivos para enjuiciar a Assange bajo la acusación de que estaba en posesión de propiedad robada; más bien, deberíamos estar planeando un mejor control de nuestras bases de datos.

La evolución de la situación en Libia

Las intervenciones humanitarias son peligrosas porque uno puede comenzar con buenas intenciones y acabar en consecuencias no deseadas. Por ello deben ser muy específicas sobre lo que realizan. Parecía una posibilidad real que Gadafimasacraría a civiles en Bengasi; por lo mismo, creo que Estados Unidos –como signatarios de la resolución de la ONU en el sentido de proteger la vida de civiles inocentes– tenía una obligación. Aunque la gente puede pensar que no era un interés vital… Quizá estas acciones humanitarias no son “vitales”, pero son muy importantes. Y Obama tuvo razón al reconocerlo, también al esperar hasta obtener legitimidad (soft power) mediante la resolución de la Liga Árabe y el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU y al expresar, asimismo, que no habría bases americanas en ese suelo ni iríamos necesariamente a la cabeza. Estarían allí por un tiempo limitado. Todas éstas me parecen formas inteligentes de tratar un problema evitando un desastre. Somalia fue un buen ejemplo de cómo, en el pasado, se acudió a prestar socorro humanitario y todo terminó como en la película Black Hawk Down. Y las cosas podría ir mal otra vez. Libia podría dividir a Oriente y Occidente. Aunque creo que Obama, al acotar el problema desde el principio, ha efectuado también un ejercicio de poder inteligente.