Graciela Hasper: The Animated Forms

John Zotos

Graciela Hasper: Abstract Geometries, Color, and Public Space

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

The ongoing dialog surrounding abstraction in painting has kept up with, if not surpassed, the equally never-ending polemics about the end of painting itself. Graciela Hasper’s prolific and engaging art debunks both of these contentions gracefully. Her paintings of colorful, animated, geometric forms are descended from the abstract painting tradition of the early twentieth century and also avant-garde painting in Argentina following the Second World War.

Hasper studied painting and theory in several universities in Argentina, apprenticed with Guillermo Kuitca, and has been awarded various prizes and grants ranging from the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas to a Fullbright scholarship through Apex Art in New York. From the time of her first exhibition in 1990 she has exhibited internationally in solo and group shows and is currently preparing for an exhibition at Sicardi Gallery in Houston, Texas in the fall of 2011.

As artists maturing in the nineties in Argentina, Hasper and her generation were forced to ask themselves what they could contribute aesthetically to a country grappling with social and historical issues such as economic upheaval and the oppression of a military dictatorship. The political situation resulted in the loss of artists important to Argentine modernism who were forced to emigrate rather than face censorship and even punishment. This meant not only the loss of artistic talent but also the loss of teachers for subsequent generations. Hasper responded with art in different media, but painting decidedly became her medium of choice, and it is through the lens of painting that she has extended her work conceptually into mixed media and installation art.

She has been loosely compared to other abstract painters like her former teacher Kuitca or even Pablo Siquier, her contemporary, but unlike their work, Hasper’s paintings are completely abstract, meaning that no recognizable forms can be found in the images. The paintings are sometimes constructed out of shapes formed into patterns that cover the surface or reveal a definite ground with intertwining shapes reminiscent of Mobius strips or DNA helixes.

For example, in Untitled, 90cm X 190cm, 2010 an abstract painting using multiple colors, Hasper assigns one color to each shape, some of which are sectioned by the perimeter of the canvas, while others remain whole. The shapes both join like puzzle pieces and at times keep a safe distance from surrounding shapes either separated by a white ground or possibly hovering above it. On a formal level, Hasper is interested in the viewer’s experience of her process in arranging the placement of shapes and colors, and the enjoyment the act of looking offers as a reward to contemplation. She devises the paintings such that no single format designates which side is up conferring the feeling that several viable views are possible rather than a single dominant version of the reality of images.

Hasper’s organization of space and the level of tension present on the surface are completely different in Untitled, 90cm X 190cm, 2011. In this painting the circular repetitive shapes, some whole and others cropped (again) by the perimeter of the canvas, reveal no space between, above, or below the surface itself. There are two places where you could suspect this but it could just be a lightly shaded circle. The color in every circle is altered by the color of the other circles that it joins to. In Untitled (2010) the shapes appear to pull away from each other creating a tension generated by a lack of unity, while in the Untitled (2011) they mix and join like cells in a petri dish with a tension mediated by layering and compression.

In this decidedly formalist analysis, her work could be compared to a number of artists in the modernist pantheon such as Malevich, Theo Van Doesburg, or Antonio Asis. Specifically, they created a type of abstract painting informed by geometry, line, plane, and color. Unfortunately, formalist criticism usually refuses, or at least fails, to recognize that painting does not exist without a historical and social context. In the case of Hasper’s paintings, an alternate critical approach reveals several layers of meaning and adds an essential component to understanding her work.

Where the work of the modernists is usually associated with the metaphysics of idealism, or utopian sensibilities, it could be argued that Hasper’s work operates on a counter register as an ironic critique of twentieth century myths of progress. In the case of Untitled (2010), the shapes could represent a topographical map of city blocks or buildings, but instead of the clean modernist designs used for city planning starting in the nineteenth century, we see a chaotic disruption of a failed paradigm. Major cities in Europe and America were designed, ostensibly, for the ease of traffic flow and commerce. This also meant that they were easily defensible against the civil unrest associated with revolution and ultimately susceptible to control. In the dialectical aspect at work in modernism, the drive for order brought about resultant phenomena with opposing tendencies. In this case Hasper’s targets are the devolution of urban space into slums, the rise of poverty, and the consolidation of power by right-wing authoritarian governments.

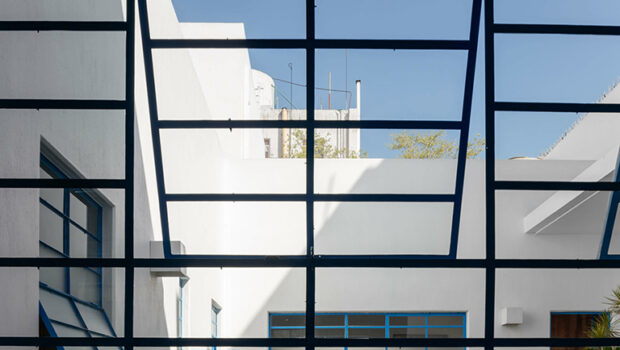

This notion that the work engages a social critique leveled at urban architectural planning becomes visible upon a consideration of a series of mixed media pieces, from 2001 such as Corrientes y 9 de Julio. In this piece what appears to be a satellite photograph of the center of Buenos Aires forms the basis for an image driven by line and geometry. The city blocks and major streets are clearly visible with the intersection of Corrientes and July 9th streets highlighted by Hasper in a vibrant aqua shade that forms an x shape that dominates the otherwise monochrome image of the city plan. These two thoroughfares come together at the Plaza de la Republica and the grand Obelisk national monument commemorating the fourth centenary of the first foundation of the city. An imposing sculpture, the obelisk bisects the July 9th Street (the date of Argentine Independence) and has become the national symbol of Argentina. Hasper thematizes the modernist grid structure of the city in order to underscore the foundational notions of the state as a republic that gained its independence from a colonial power. But, the disconnect between these enlightenment ideas and the administered, calculated, conformist design of the city becomes clear in her aesthetic treatment of the image with the color and line of modernist grids. Argentina’s recent history has shown how threadbare and fragile cultural and social freedom can be, and Hasper’s work argues that for all the design acumen and architectural abilities that went into creating the modern metropolis they did not immunize the population from tyranny. The piece suggests that perhaps new social relations and liberating experiences could possibly be retrieved by concentrating on the notion of an independent republic (the plaza, the obelisk, urban intersections) by way of the social interaction and dialog that are the things that are supposed to happen in a public space. Hasper privileges these ideas by her addition of color to the symbolic avenues and the plaza while the banal predictable geometries of the city blocks remain monochromatic, referring to their failure to mobilize the ideas represented by the areas she highlights.

This is also at work in Untitled (2010) in that the clearly disrupted geometries of the odd shapes refuse to give way to the clear pathways and vistas of modern urban city planning. Instead, comparable to Situationist art by Constant or the ideas of Guy Debord from his book The Society of the Spectacle (1967), Hasper’s shapes, if representative of city blocks and streets, argue for an experience based derive (a non-linear stroll meant to alter ingrained thought patterns) through winding indirect paths that encourage interaction and the occupation of space.

Just as Hasper’s paintings and mixed media pieces offer a critique of dominant systems of power that construct fictitious social relations and national identities, her installation project at the Chinati Foundation mounted a negation of minimalist dogma. In the 1970’s Donald Judd began to purchase land and the remains of Fort D. A. Russell in Marfa, Texas with the aim of exhibiting and preserving his art and that of fellow artists John Chamberlain and Dan Flavin. The foundation ultimately opened to the public and offers residency programs and exhibitions. In 2001 Hasper was awarded a residency at Chinati and occupied the specified buildings designated for recipients in which she created her project.

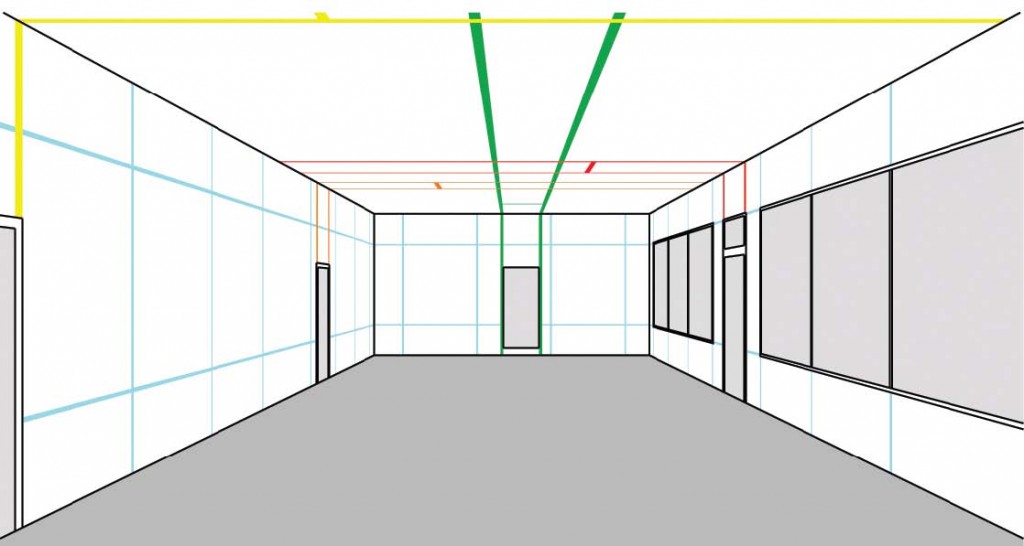

For her Chinati installation, 2002 Hasper applied pastel colors in lines and strips along a grid pattern to the interior spaces of the buildings, sometimes carving into the floor and staining the color into the scored areas. The lines sometimes traced the original architectural elements in the rooms, but not always. Minimalism disdained references to objective reality and the gesture of the artist and this decorative overlay negates its purity of design and monochromatic tendencies. The lines are at odds with the natural order and geometry of the interior and they provide the antithesis of minimalism’s serial aesthetic, often called ABC art or literal art in the criticism of the time. In his book The Return of the Real, Hal Foster argues that minimalism paved the way toward the postmodern turn in art. If so, Hasper reveals her position as an act that seeks to deflate postmodernism’s relative and indeterminate version of reality rooted in ambiguity.

In 2004 Graciela Hasper’s art was included in the publication of Manifesto of Affirmationism by Alain Badiou. A devout critic of the genealogical tradition, the hermeneutic tradition, and most importantly of postmodernism, Badiou’s philosophical system theorizes that truth can be found through the fidelity to a groundbreaking event that can ultimately lead to real social change. Hasper’s art identifies with this view because she understands that universality, not hierarchy and ambiguity, paves a path toward a just society.

Posted: May 21, 2012 at 11:02 pm