A Prodigious Dustbin Flower

Prodigiosa flor del basurero

Adriana Díaz Enciso

Origins

He’s a true dickensian hero. The son of Irish immigrants, he grows up in poverty in the north of London. At seven he contracts meningitis, infected by the rats in his home’s courtyard, falls into a coma that lasts months and when he wakes up, he finds he’s lost his memory. On leaving hospital he goes back home with no other choice than believing that the man and woman who claim to be his parents really are so. It takes him four years to recover his memory; that, and the many sequels of the illness, make him shy and solitary. His refuge is the public library. He’s fallen behind at school, where he faces the rejection of other children, who find him odd. His sharp intelligence and love for books, joined to a certain talent for comedy, finally gains his schoolmates’ acceptance, particularly when he uses his talents to challenge teachers, from whom he doesn’t think he’s receiving any education at all. Personal adversity won’t stop him from taking on his responsibility as the eldest son, and he spends his childhood looking after his three brothers. On occasions, also after his sickly mother, prone to miscarriages. He’s a streetwise kid, and though reserved and fragile, he won’t chicken out of fights when it’s required.

To pay for his further education and contribute to the household’s economy he works on building sites. His avidity to learn it all, specially literature and history, is enormous. His shyness becomes a fierce will to be an individual. As a teenager he paints his hair green and his father evicts him because he looks like a Brussels sprout. To be on the dole depresses him: he knows it’s his right, but the humiliation inflicted on those who have no more options offends him. He then works in a shoe factory, as well as in a day care centre for children ‘with problems’. He loves playing with them, teaching them how to make airplanes out of wood, though his employers see him with misgivings because of his outlandish appearance. Later on, he’ll work as a cleaner in the restaurant of a department store, along with one of his best friends, who will later appear, tragically, in this story.

Towards the end of the 1970s he can often be seen among the disaffected youth who frequent King’s Road, in Chelsea, when England, rising slowly and painfully from post-war, is crumbling because of class divisions, the poverty of many, continuous riots and police brutality. An exemplar of urban picaresque, selling amphetamines since money’s short, he’s well aware of living in a system which leaves pretty few options outside criminality for kids like him.

But crime is not his thing. What he wants is equality, and the empire of truth: for a world that wakes up or explodes if not. His attitude, both defying and distant, calls others’ attention. It’s reflected in the way he’s dressed. He’s seen with a Pink Floyd t-shirt full of holes, where he’s written I hate above the band’s name. Malcolm McLaren, a twisted character in London’s counterculture who, along with designer Vivienne Westwood, runs a boutique called Sex, invites him to a singer audition for a rock band he represents. Though he loved music since he was a child (he’s always been the DJ in family parties), our hero has never sung. In the Catholic school he attended he had tried hard not to learn to sing, so as not to attract the priests’ dangerous attention. However, he goes to the audition: he sings the cover of an Alice Cooper song. The fury and daring of his delivery give him the job.

His figure already bent by meningitis, the pain and dizziness which make him stoop even more, the mad stare with which he tries to focus his eyes, weakened as well by the illness, are all elements which he uses in his favour in order to create an onstage presence that negates all of the rock star’s conventions and underlines the incendiary nature of the lyrics he writes. He’s nineteen years old.

The sudden leap to infamy will come laden with tribulations, but he will fight his way, will earn the respect which was his right and will end up adored by millions of people, turned into a kind of national treasure. One day he will declare: ‘I come from the dustbin’, and will thank the public libraries system for having taught him, during his childhood’s lonely hours, to learn to use words as grenades against the political and social system of a country which, by the time he was 21, had already tried to lynch him.

Sex Pistols

rock’s history is strewn with young corpses. That Johnny Rotten wasn’t one of them is astonishing, and not so much for his not having succumbed to the sex and drugs and rock ’n roll triad, but for having survived the public persecution of the Sex Pistols, as well as the ostracism imposed by his bandmates and the humiliations at the hands of their abject manager, not to mention the aggressions he became the butt of when he left the Pistols, coming from the press as much as from a fossilized punk scene which hadn’t understood anything at all (but not even the other Sex Pistols seemed to ever understand anything). Whether John Lydon’s (the name he was born with) hard-won esteem will survive his recent statements about voting for Trump, now that he’s a US citizen, will be touched upon further on.

The Sex Pistols’ story has been told many times, from different perspectives. I believe it the way Lydon tells it because the evidence is everywhere. To prove it, we just have to take a look at later interviews with all the actors in the drama, to the loathsome film The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle (1980), directed by Julien Temple and instigated by McLaren (though, it has to be said, you need stomach to bear it), or The Filth and the Fury (2000), a documentary also directed—schizophrenically—by Temple: McLaren and the other Pistols incriminate themselves. Despicable, sinister by dint of sheer banality and mediocrity, we have yet to concede that McLaren, since we’ve started these pages mentioning Dickens, more than achieved his longed-for stature as a novelesque villain.

The Sex Pistols were guitarist Steve Jones, drummer Paul Cook, bass player Glen Matlock and Rotten as the singer, apart from writing the songs’ lyrics. In 1977 Matlock was replaced by Sid Vicious. We know that the Sex Pistols were an explosion that revolutionized rock music out of its complacency, the violence of which raised a mirror up to a corrupted society.

These notes do not focus on them, but on Lydon (aka Rotten); on his fierce intelligence, his artistic integrity, and his perplexing resilience, but that’s where we have to start. The resentment among the Sex Pistols’ former members will probably never dissolve—it was there from the beginning. Johnny Rotten joined the band when it was already formed, manager included, and as it was, he ended outshining them all. With his seditious lyrics and ferocity onstage, he would turn a group of talented but aimless kids into the most famous (or infamous) rock band in the world at that time.

Rotten had singular weapons in his arsenal: his attentive study of Shakespeare (whom, in his opinion, should be performed with the people’s voice, rather than made decent by Oxford and Cambridge) was one of them. Others were his passion for oratory and history, his delight in the tradition of English comedy, and the thorn in the flesh of the lack of opportunities for the working class. He wasn’t, as the press would imply very soon, a nihilistic delinquent. He wanted, to use a hackneyed expression, to better himself, though he didn’t know how or whether it was possible, and he was, that’s for sure, full of rage. The weapons in his reach were faculties he had cultivated, and all of them would be explosively combined in the birth of Johnny Rotten, Sex Pistol. They burn gloriously in that howl of fury, despair and defiance that is “Anarchy in the UK”: in theatricality as the vehicle of visceral emotion; in the harsh rolling of the R’s, the distorted vowels, the snap at the end of the dislocated phrases; in the body as a whip with which to lash the irate words, showing that a song’s force is more than the mere combination of words and music.

McLaren was malignant and mediocre, but he wasn’t stupid, and he sized up from the outset Rotten’s virtues as the band’s leader. However, he liked talking about his first impressions of him singing “like the hunchback of Notre Dame” and, in The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle, he’d describe him in “an attitude that made him look like crippled, kind of vulnerable. And I liked that”. He was part of the “clay” which, according to his fantasy, he had moulded; one of the human beings he had manipulated in order to shock everybody and take them for a ride while he lined his pockets. In The Filth and the Fury, which gives the former members of the band the chance to tell their version of the story, Lydon finds instead a smart and luminous way to appreciate his vulnerability, as he talks of how the character of Richard III had helped him when he joined the Sex Pistols: “deformed, hilarious, grotesque, and then the hunchback of Notre Dame is there, all these bizarre characters, but somehow, through all of their deformities managed to achieve something.”

Lydon found the people who walked in trendy clothes down King’s Road, oblivious to the fact that England was crumbling, absurd. His sardonic look on the new S&M vein of his boutique’s merchandise and the spectacle of people who had to subject themselves to the discomforts of such outfits to have sex, because they “were incapable to face reality”, cannot have gone unnoticed by McLaren. He wouldn’t have managed to ignore either that this boy was no mouldable clay, and that he obeyed orders from no one. His strategy was then to divide and rule, making sure that Rotten was scrupulously excluded. He wasn’t invited to the parties with the rest of the band; while McLaren found accommodation for them, Rotten kept on going from one place to the next, as he had nowhere to live. Here we should remember that the Sex Pistols, a world rock phenomenon during their brief history, had no money. McLaren paid them peanuts per gig, of which there were few, and pocketed the rest or invested it in his own projects, including his awful films, with which he was eager to exploit the band’s fame.

Manipulating the other Pistols wasn’t hard. For them as well, Rotten was “different”, “difficult”. “He was the intellectual”, Steve Jones would say later. In their defence, we should remember how young they all were, and the harsh circumstances they came from, Jones in particular—the Sex Pistols were all he had. His only other option would have been delinquency.

When Matlock leaves the band, Rotten makes a mistake, inviting John Simon Ritchie (whom he had renamed Sid Vicious in honour of his hamster) to replace him. Vicious couldn’t play the bass, but he was the number one fan. Rotten thought he’d be an ally who’d make his isolation bearable, but that’s not how things worked. Vicious, the son of an addict who gave him heroin as a birthday present, was perhaps the most fragile of them all. Sudden fame, his relationship with groupie Nancy Spungen and McLaren’s division tactics led him to a spiral of self-destruction which, as is well known, would culminate in Spungen’s murder, of which he was accused (though the case is still inconclusive and was never thoroughly investigated), and in the heroin overdose which ended his life at 21.

Between his joining the Sex Pistols and his death, Vicious honoured his name. He wanted to be the toughest of them all; responded with violence to the audience’s provocations, and on occasion found in the bass he could not play an effective weapon; he competed with Rotten on stage to show who was the “real” punk. There are some unsettling videos that show him playing bathed in blood, the product of self-mutilation or some brawl. McLaren, thrilled with the growing chaos, egged him on. Johnny Rotten was still on his own, now sickened by his friend’s behaviour and by the distortion of the music they made, which had become buffoonery.

From a distance, it’s hard to understand that society had a nervous breakdown because of the mischief of four youths, one whose nickname was Johnny Rotten because of the state of his teeth, the other’s Sid Vicious thanks to a hamster. We cannot doubt that sensationalist media were more responsible than the Pistols themselves, who assaulted the national psyche when interviewed by Bill Grundy for the Today programme in Thames Television on December 1976 (when Matlock was still in the band). Grundy was as drunk as the interviewees, and evidently bent on provoking them. After goading them, with considerable success, to swear in a live programme, the Sex Pistols became the embodiment of the threat to national morals. The tabloids’ headlines the following day would have you think that the press had no more serious problems to bother about; “The Filth and The Fury” is one of the most memorable.

There were public protests (one truly outlandish, with the demonstrators singing carols). Most of the band’s gigs were cancelled and they ended up using pseudonyms in order to be hired, such as S.P.O.T.S. (Sex Pistols On Tour Secretly). EMI, with whom they had just signed a contract, fired them. True, the kids were ill-mannered, but the panic unleashed was sheer collective hysteria. Or a mediatic circus, which is basically the same. When the London councillor Bernard Brook Partridge declared in TV that punk bands would be “vastly improved by sudden death”, that the Sex Pistols were “unbelievably nauseating”, “the antithesis of humankind”, and that he would like to “see somebody dig a very, very large exceedingly deep hole, and drop the whole bloody lot down it”, since “the whole world would be vastly improved by their total and utter non-existence”, I hope there will have been someone who wondered which side the greatest violence came from.

God Save the Queen, a Christmas, and the end

Things escalated with the release of the single “God Save the Queen”: “God save the Queen. She ain’t no human being. There is no future in England’s dreaming.” What would the keepers of morals do now? It would doubtless be ridiculous to unbury some ancient law in order to accuse the Sex Pistols of treason, lock them up in the Tower of London and chop off their heads. For a start, their second record company, A&M, dumped them too —I think they didn’t last more than ten days—, after a particularly unbridled meeting in their offices. Finally, Virgin had the nerve to hire… and not fire them, but releasing the single wasn’t all that easy. There were workers who refused to press the vinyl or print the cover. After much negotiation, it was released in May 1977, shortly before the Queen’s silver jubilee, but many radio stations refused to play it, and stores to sell it. A curious reaction, as Rotten (still indignant) reflects in The Filth and The Fury: “You don’t write God Save the Queen because you hate the English race. You write a song like that because you love them, and you’re fed-up with them being mistreated!” He knew he had written an alternative national anthem.

He meant it: “When there’s no future, how can there be sin. We’re the flowers in the dustbin. We’re the poison in your human machine. We’re the future: your future.” Rotten recalls: “What we offered to England—we were the maypole that they danced around”. To him, the message was obvious, and he would resent the violence he received in return. With his face all over the national press, to be out in the street was suicidal. Blows were one thing, but not even his street life education could protect him from the violence which had unleashed against him. The worst attack was with knives and a machete. When he went to hospital, seriously injured, he was arrested for “suspicion of causing an affray”. Only then did McLaren bother to find him a safe, low-rent place to live. As I’ve already mentioned, these public enemies weren’t earning money from gigs, and they still hadn’t seen their share of the record companies’ advance. It was them who were unprotected, not society.

We must admit that McLaren’s idea of renting a boat to play in front of Parliament on Jubilee Day was brilliant. In the footage, among the euphoric entourage of fans and press and McLaren’s friends, we can see Rotten alert, like an animal in danger, and it wasn’t only amphetamines: “have you got the feeling you’ve been trapped?”. Half-way through the gig the Thames police managed to stop the boat. There were many arrested, McLaren among them. Rotten escaped because he made sure he’d be one of the first ones to reach the pier; when a policeman asked him, “Where is Johnny Rotten?”, he answered “up there”, trusting that back then it was long-haired guys who got arrested. Of that night Lydon remembers particularly the cold: the one outside and his own. He was “definitely undernourished”.

That week God Save the Queen reached number one in the hit parade, but the BBC refused to acknowledge it. Number one was empty, and only number two was promoted: a Rod Stewart song.

By then Rotten already knew that the foundations of the Sex Pistols were being distorted. For him, there never was a real punk movement; it had been corrupted from its birth. He was depressed by the literal interpretation that it was a matter of being “bad”; by the audience who threw at them all sorts of projectiles, expecting to see a freak show; by the uniform that started to define the punk fashion, the rich kids with their leather jackets that the members of the Sex Pistols couldn’t even afford. Ever since, Lydon/Rotten has tirelessly said that punk’s original message was positive, as the spark to ignite a political and social transformation, rather than the instauration of some kind of fashion; that he never believed that violence was the solution to anything; that what he has believed in from the beginning is passive resistance (and he certainly has exercised it). In his autobiography Anger is an Energy he talks about the bands which wanted to “out-Rotten Rotten”. That’s were violence was infiltrated: “Dumb, moronic, smashing-their-heads-off-walls-to-show-how-tough-they-were fools. They weren’t listening to nothing. They were incapable of learning, or growing with a thing, or seeing any hope or prospects for the future. We were saying “No future” in ‘God Save the Queen’, because you had to express that point in order to have a future. No, these lot really didn’t want one.”

Around that time, he was invited to play albums from his own collection in Tommy Vance’s programme for Capital Radio. There he showed that his musical knowledge was vast, eclectic, and that his enthusiasm was not limited by labels. McLaren was very annoyed and accused him of “ruining punk”. According to him, Rotten’s obligation was to always present himself as “dangerous”.

The band’s only album, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, appeared in October 1977. Virgin was taken to court accused of indecency for using the word “Bollocks”. Rotten volunteered to go to court. It was important for him to defend the right to use a term which according to the Oxford dictionary itself was perfectly acceptable, and to challenge the prohibition of any word. Nobody else showed up. Not even McLaren.

The battle that Johnny Rotten was leading in the Sex Pistols wasn’t the same in which his bandmates, his manager, the press and even a great deal of their audience were engaged in. Loneliness must have been profound.

With all the gigs cancelled, December 1977 was a depressing month for the Sex Pistols. They started to travel around the north of England looking for places where to play, but everywhere they were rejected. Yet something exceptional would take place in Huddersfield, when the Pistols found out about the precarious circumstances of the firemen who were on strike, demanding better salaries and work conditions; for weeks their families had been depending on donations from sympathetic people, and their Christmas would be a gloomy one. Suddenly everything made sense: that’s where the Sex Pistols had to be. They offered two benefit gigs—a matinee for the firemen’s children, and a later one for the adults. The 25th of December nothing moves in the United Kingdom. There isn’t even public transport, and it seems that then it was even illegal to have a concert. But they wouldn’t ask for permission.

In 2013 the BBC rescued footage of that unlikely Christmas in the documentary Never Mind The Baubles—Christmas ’77 with The Sex Pistols. There we can see the Pistols before the matinee playing with the kids. Rotten serves them cake. The band arrived with presents, food, the gigantic cake. Even Sid Vicious looks calm and happy. The children dance wearing their Never Mind The Bollocks t-shirts. To their delight, Rotten announces: “We’re that horrible people you’ve been hearing about, and we’re going to play some songs”. Rotten is clearly singing for them (editing the swearing in the lyrics), and with them. Interviewed in the documentary, he says that the kids understood perfectly what it was all about: “that we were children like them”. There, they couldn’t strike their tough guy poses, because the children would realise it was false. “With them you couldn’t be the worst Johnny Rotten. You had to be the best Johnny Rotten.” The adults were delighted too. So these were the monsters who were going to destroy the country? The only ones who cared about the striking firemen and their families having a decent Christmas? Then things did really get punk, when Rotten stuck his face in the cake and the children started to throw more at him. “That’s when Sid realised that he was a kid after all”, he would say later. “How can you be tough with a Christmas cake in your face?” Perhaps this is the only Sex Pistols footage ever in which Johnny Rotten looks happy, and in which all of them, as a band, seem to be in the same frequency. Steve Jones tells of how around that time he was depressed, and how playing for the striking firemen helped him to come out of himself. That was their last concert in the United Kingdom. The surviving ex-members of the band seem to agree that it should have been the final one, the dignified and coherent way to close their story. But the American tour was to come, which would finish them off in two weeks.

If someone wants to understand who the Sex Pistols really were, I think what they have to see isn’t the history of tabloids’ scandals, the naughty boys prodded by the press, the film Sid and Nancy or McLaren’s idiotic films, but the record of that Christmas in Huddersfield.

The US tour was hell. McLaren didn’t start it taking them to play to New York or California, where a more open and enthusiast audience was waiting for them, but to redneck venues in the southern states. McLaren himself would later admit that he wanted a hostile audience. He rented low quality PA systems and monitors. He wanted not only circus and scandal, but carnage. While the others stayed at fine hotels, Rotten and Vicious slept in motels. They travelled in a school bus; the others later continued the tour flying, but not Rotten and Vicious. Lydon remembers however the wonder of those fabulous, new infinite landscapes seen through the bus window with his friend. Yet he could also see how the latter was sinking. Sid Vicious was a broken boy. His notoriety with the Sex Pistols was his only power. McLaren poked the flames making him believe he was the true star, and that he was very, very bad. During the tour Vicious became, to the press’ delight, a sad spectacle of addiction and violence. It wasn’t for that that Lydon had written those songs, he says in Anger is an Energy, nor what Jones had created the band for. He talks about the pain of witnessing his friend’s downfall; of his rage too, and the disappointment that there were people in the audience believing that was cool. “His example is one of self-destruction. How is that appealing? And then you’ve got a media ready to package that, because it takes away from the political content of them songs. Suddenly there’s not a real serious social message, there’s just a drug addict.”

They were all exhausted, and there were continuous quarrels. Rotten wanted to convince his bandmates they should get rid of McLaren; else, he feared, “someone’s gonna get killed.” What followed instead was his total segregation. McLaren refused to talk to him and managed to block communication with Jones and Cook. On the last tour date, in San Francisco, Sid vanishes, just to show up before the concert, smacked. Rotten decides he doesn’t want to be part of that farce anymore. During the encore, a cover of No Fun, by The Stooges, Rotten is already out of the Sex Pistols. His isolation is manifest, his delivery a howl of disillusion: of the band, of himself, of the audience. Vicious jumps around with lost gaze like a living dead. Half-way through the song Rotten asks himself: “Bollocks, why should I carry on?”, desolation stark on his face. But he does carry on. Desolation is his swansong, and no one notices. He ends up crouching, the very embodiment of the song’s lyrics: “This is no fun, at all. Alone, no fun, by myself, no fun”. Then, disenchanted, he stares at the audience that shouts and dances, oblivious of the drama unfolding onstage. He laughs joylessly and asks, “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated? Good night.” He drops the microphone and leaves the stage. That was the end of the Sex Pistols.

Jones and Cook fly off to Brazil without saying goodbye. Nobody answers his calls. Rotten is all alone in a hotel, the bill of which no one has paid, without money or credit card. He didn’t even have a bank account.

To McLaren though, it wasn’t the end. He insisted on finishing The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle, with which Rotten had already warned him he wanted nothing to do. For his part, McLaren used archive material. He also hounded him to film him in secret, all the way to Jamaica even, where the record company had sent him scouting for reggae artists. The film is as vile as it is fatuous, with McLaren behind his leather mask saying how he’s fulfilled his goal of making a fortune through the manipulation of the human clay of four boys who, according to him, had no talent whatsoever, creating chaos and anarchy. Sid Vicious is, of course, the star, and he’s utterly vicious. Indeed, someone did get killed, and it was him. McLaren probably knew that it couldn’t end any other way, but he didn’t care. His intention seems to have been to destroy them all, so as to create the myth of his own omnipotence. It’s still incomprehensible to me that the other Pistols agreed to take part in that film. Regardless how young or lost they were, didn’t they really ever realise that the band was about something else? Maybe not—that something else was what Johnny Rotten, the new one, the difficult one, brought to the Sex Pistols, what transformed the musical scene and was a slap on the face of a slumbering society. Hence perhaps the resentment. Perhaps they always wanted to be just another rock band.

In The Filth and The Fury John Lydon reiterates his regret for having invited Sid Vicious to join the Pistols. He was too vulnerable. He says he wishes he hadn’t been so young himself, then breaks down: “I feel nothing but grief and sorrow and sadness for Sid. He died, and it all for the money. I will hate them forever for that. It can’t get more evil than that. Vicious, poor sod.”

McLaren had kept the Pistols’ money, the rights over the band’s name and material, and even the name “Johnny Rotten”.

Perhaps another 21-year-old would have succumbed in such circumstances, but, as Lydon likes reminding us, not Johnny Rotten. He took McLaren to court, having everything to lose, but won the case eight years later. He succeeded in having the surviving members of the band share all the rights and receive equal shares of whatever was left in the bank, after paying an enormous bill of overdue taxes.

Public Image Ltd

From the moment he left the Sex Pistols, Johnny Rotten demonstrated that he was nothing of what the audience, society and a corrupted musical industry wanted to force him to be. He wouldn’t fit a single cliché. He was no stray bullet. He wasn’t even interested in the one-night stands that are deemed obligatory for any self-respecting rock star. He found all that, as much as a great part of the society around him, absurd, and started a relationship with Nora Forster, who’s still his wife to this day. In 1978, while branded by everyone as a scourge, he was the first to denounce in a BBC interview the TV and radio presenter Jimmy Savile. That part of the interview was censored, and Savile lived a long life of honours and awards, which include an OBE. Only after his death was what Rotten had already warned that everybody knew—that he was a paedophile, with a long record of abuse of minors—revealed.

Where the abyss between what he was and what people expected of him became clearest was in the creation of Public Image Ltd (PiL), with Keith Levene (guitar), Jah Wobble (bass) and Jim Walker (drums). He was again John Lydon (since McLaren had snatched away from him the right to use his own nickname). “Horrified by the cliché of what punk was becoming”, he ventures with his bandmates in the exploration of a vast musical universe devoid of rules. The first album, First Issue, starts with “Theme”, a long and hypnotic piece led by dislocated, biting voice and instruments as far from punk as it’s imaginable. Lydon’s voice is still recognisable as Rotten’s, yet, exacerbated, seems to come from another dimension. It is both the liberation cry and the lament for what had happened with the Sex Pistols. “Another leap in the dark. I will survive. And I wish I could die”, I wish I could die a howl ensnared in the claustrophobic instrumental loop.

The album is a superb avant-garde shock. Pure genius—complex, intense, abrasive, it hasn’t aged in all these years. It also includes more accessible themes, though no less impetuous, the triumphal advent of New Wave, such as “Public Image”, a challenge to McLaren as much as an assertion of Lydon’s independence. In First Issue Lydon begins to explore new expressive forms with his voice, developing a style which is both unique and chameleonic. There is also theatricality and irony. It’s a leap into maturity which must have perplexed Rotten’s persecutors. But it didn’t make them listen with more attention, nor stop harassing him. The audience was stuck in the Sex Pistols’ racket and didn’t want to know anything else.

By then Lydon had already accumulated all possible proofs that the pop and entertainment industry was completely corrupt, and since then he’s unflinchingly kept on exposing it every time he has a chance. Or even when he doesn’t. This, of course, didn’t do much to improve his standing. He earned a reputation of being arrogant, rude(r), insufferable. In truth, it’s a delight to watch him demolish journalists with a couple of lapidary phrases, terrifying them, purblind and all, with his gaze and with the piercing weapon of his intelligence, often getting up and leaving them talking on their own. A strange creature—sophisticated despite the swearwords, elegant even, just to suddenly crown it all with a belch. Who was this boy? A lad of the street with terrible manners? The intellectual Steve Jones talked about? A genius? He was all three.

Journalists hated him. They didn’t have enough brains to understand that the stupidity and banality of their questions deserved no other answer than arrogance. Or that it was offensive to ask him only about the Sex Pistols’ scandals in the tabloids and show no interest in the new music that he was creating with PiL, which was utterly interesting. Or that it was downright sadistic to invite him to do an interview just to tell him that the audience didn’t like him , show him a very long video where some very angry individuals say that Johnny Rotten is “finished”, the camera fixed on his face so as not to miss his slightest reaction. He must have needed nerves of steel.

Talking about Lydon/Rotten’s arrogance has become a tradition. There is little talk in my view about his dignity. He wanted people to pay attention to the music and not to let themselves be fooled by the media and record companies, and it is a joy to watch him fighting that war. One example is PiL’s appearance in 1980 in the American Bandstand programme. They had been asked to use playback; that is, to deceive people. Their performance starts with Lydon sitting down, without even pretending that he’s ready to start singing. Then he walks among the audience and starts leading them onstage. There is an element of comedy (he pulls people by the hand, shoves them, dances with them), and also subtlety, a beautiful and light way of saying, “what matters is music, people”. They all end up dancing, and Lydon manifestly passes from boredom to joy. It’s a moment that mirrors the Pistols’ Christmas in Huddersfield, and John Lydon’s true image.

A year before he had appeared in Jukebox Jury, resolved to lay bare the sham behind such programmes. The jury which will supposedly assess the wretched list of hits with pretentious musings includes Joan Collins, of all people. The presenter starts to get annoyed with Rotten and asks him what kind of music he likes. “Decent”, is the terse answer, and as the presenter still tries to corner him, he adds: “I won’t ram it [the music] down your throat”. Another member of the jury pokes him too, but Rotten won’t get hooked in the farce. The audience laughs, and he is indeed very funny, but he’s in earnest. At the end, when the presenter wonders whether if the listeners will agree with the jury, Rotten interrupts: “I wouldn’t be talking about the listeners, I’d talk about the people that broadcast them [the songs]. Big difference. Good night”. And walks off.

In Anger is an Energy Lydon says: “That’s what music wanted from me [. . .], and it’s not going to happen. Not ever. I don’t need to find a niche in that kind of society. The more they annoy themselves about my kind of personality the better it is for me, because I honestly don’t think I’m doing anything wrong here.”

He’s right. But there’s been no insolence that “that kind of society” hasn’t tried to make him pay for, and it’s hard to think of anything that Rotten/Lydon has ever said or done publicly in more than forty years that hasn’t been considered an insolence by someone, somewhere. It cannot be easy. PiL’s beginning wasn’t easy either. If people wanted anarchy, PiL is one of the most anarchic bands there’s ever been, with a nearly suicidal eclecticism and lust for risk. Not everything works, but what does (and it’s most of it), is magnificent, and it’s a privilege to accompany them in the journey. Punks didn’t see it that way. The immediate accusation was that Johnny Rotten had sold out. Such an accusation, coming from that place, can have serious consequences: during a concert someone climbed onstage to stab him with a screwdriver—it was blunt, luckily.

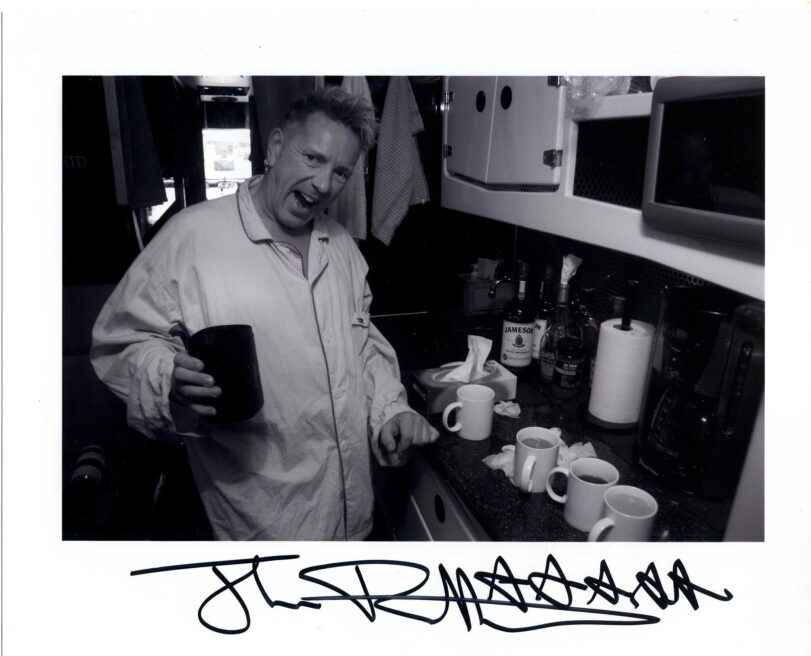

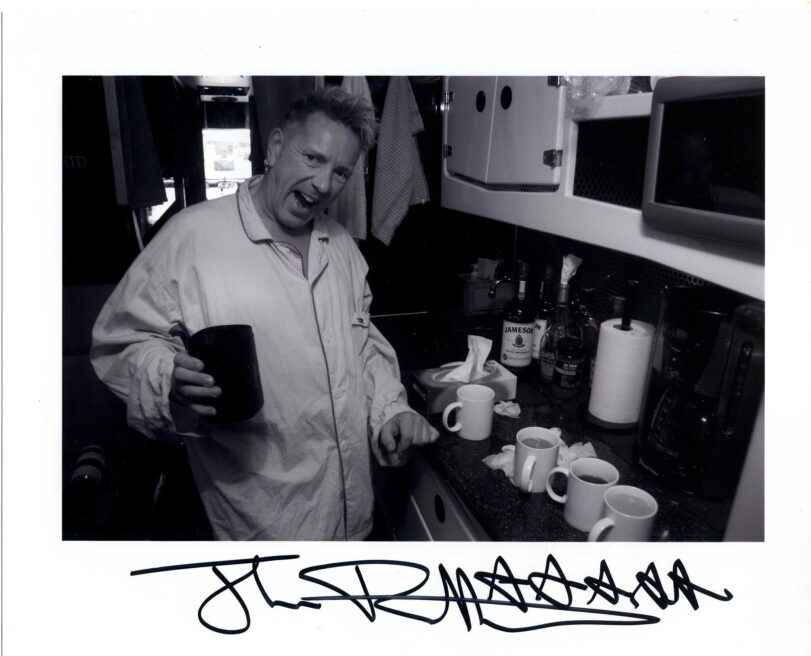

What about the rest of society? If the press wouldn’t leave him alone, nor did the police. Apparently the MI5 still has an open file on Lydon. Raids on his home and the not so hidden spying became so frequent that he got to know by name some of the police who prowled around him. It wasn’t only when there was a party that they smashed his door down. It could be any day, at any time. With no explanation, and no charges. Once it was at dawn. They took him to the police station just to then let him ago; again, no charges. They hadn’t given him time to take money for a cab or bus; he went back home walking in his pyjamas. It is hard to understand the fixation of the authorities on humiliating a singer this way.

During a visit to Dublin he was unlucky enough to receive similar treatment. His appearance wasn’t much approved of among a pub’s patrons. The police intervened. He says, not without humour, “I attacked two policemen’s fists with my face”. He wasn’t immediately arrested. Somebody followed him to the hotel. It is likely that it was finding out who he was what led to his arrest. He was accused of aggression and of having called the barman “Irish pig” (something quite unlikely, as both his parents were Irish), and he was refused bail. He spent a weekend at the notorious Mountjoy prison, where there were also ERI and UDA terrorists. Lydon continues:

“On my arrival, the warders decided to make an example of me. They stripped me, threw me into the yard and hosed me down [. . .]. Over the years I’ve noticed that when these institutions get hold of you, the one thing they’re trying to embarrass you about is your nakedness, and your penis. Let me tell you, Johnny’s got a perfect penis to laugh at, and he don’t care. That’s not ever going to be a problem.”

He was sentenced to three months, but appealed, and he was released in ten minutes; no witness showed up at court. It was all a farce. Lydon went back to London to keep on working right away on the album Flowers of Romance, and didn’t return to Ireland in over twenty years. His rage about that incident is documented in the disjointed and irate “Francis Massacre”.

Eventually, the constant raids on his house for no reason at all contributed to his decision to go to live in the United States but travelling wasn’t easy either. Every time he went back home, he had problems with immigration, since the United Kingdom still kept a criminal record for possession of amphetamines from the 70s. When, wearied, he finally got the American citizenship, the issue was repeated in the British airports, even when he went back to London, dejected after hearing of his father’s death.

John Lydon as the controversial and foulmouthed bloke is one of the tritest commonplaces in showbusiness media. Little is said though about the innumerable ways in which one of the most principled artists in the hardly principled music industry has been constantly humiliated and provoked. Johnny Rotten has been more of a target for the police for being a musician defending his right to creation than if he had lived a life of delinquency. Integrity must be the cause of the problem.

One of the clearest proofs of such integrity is PiL’s long trajectory. There was some idealism in its foundation. Lydon wanted it to be more than a band; hence the “Limited”. It would be a kind of creative centre which could encompass other projects, and the musicians would receive a weekly salary so that they never had to go through the hardships endured by the Sex Pistols. They would create audacious albums out of their sheer love for music. They wouldn’t give in to the commercial demands of any record company or producer. When MTV emerged and music videos became the top marketing instrument, relegating the music on behalf of image, Lydon found the amounts of money that are usually spent in producing them obscene, and decided that PiL’s videos should always be made the cheapest possible way, often not without an element of satire of the very concept of the music video. PiL’s refusal to create “hits”, and their insistence on doing whatever they wanted instead, was a cause of exasperation for Virgin. An extreme case was when a famous engineer, who had worked with the Rolling Stones, showed up for the recording of their second album, Metal Box. PiL wanted the bass to be the axis for the whole sound. The voice was set at lower levels than usual in order to create an atmosphere, to lull you “into a false sense of security—or a false sense of insecurity. Either way, it’s getting into your mindset and it’s affecting your perceptions of the world around you. At least that was my ambition: making you think bigger things”, says Lydon.

The producer didn’t understand this sense of experimentation and insisted on pointing out that you cannot have so much bass on a record. “Yes, you can. This is how. This – is – how!”, continues Lydon in his autobiography. As the producer persisted, “I got up on the desk and walked across it in my steel toe-capped shoes and broke every button. ‘I’m not here for you to tell me what to do!’” You wanted punk? There you are.

And it’s so good that Lydon broke those buttons, because Metal Box is indeed a delirious album that doesn’t sound like anything that was being made in music then, and it still intrigues, delights, and disturbs. It is a dark record in which sonic experimentation opens the door to inner atmospheres, which reflect the hermetic images in Lydon’s lyrics taken to the point of maximum tension by his voice. Embodying human pain and being able to convey it was part of the aim, as is the case in “Poptones”, written after reading the news of a young girl who had been brutally raped. There is also a wink to Keats, a distortion of the Swans’ Lake main theme, and its complex amalgam of subtle references and transgression of all musical limits makes of it one of the best albums in rock history. The drawing near of contraries so dear to Lydon is exemplified in “Death disco”, which came into being when his mother, dying of cancer, asked him to write a song for her. The result is a visceral lament of loss, presented as a disco song in a claustrophobic video of teasing darkness, pierced through by the raw pain in Lydon’s delivery. As so much in his work, its ultimate meaning is ungraspable. About its creation, he would say: “To our punk followers, it was saying: ‘Look, why are you lurking in the shadows, boys and girls, get out there under that glitterball. Here’s your opportunity! And get a load of it, you’re dancing to the death of my mother, you bastards!’”

There isn’t enough space in this already lengthy portrait to analyse the whole of PiL’s trajectory, but it must be said that it’s a wellspring of wonders. All of pop and rock styles pass through it, but also concrete and even Renaissance music; form and content are ceaselessly transformed in the kaleidoscope of a creative quest laid bare. PiL has had the honour of producing an album catalogued as the least commercial one of all times in rock’s history: Flowers of Romance, a delirium sustained by percussions from beginning to end. There is also the sophisticated approach to heavy metal in Album: heavy and elegant (the latter being something that heavy metal isn’t usually distinguished for). Every tendency that passes through PiL is turned on its head. Music slips away like a salamander, resisting all classifications, all labels. It is also fascinating to listen to the evolution of experimentation in Lydon’s voice, through a rigorous search of form not devoid of theatricality, despite his lack of formal education. In Lydon/Rotten, being an autodidact has always been a privilege.

Lydon’s singularity has led him to paradoxical situations: some accuse him because he doesn’t do what they expect of him, because every record is different, reaching the conclusion that “he’s sold out”. On the other side there has been his record company, despairing because he doesn’t sell out, because of his refusal—which to them must have seemed almost perverse—to produce a “hit” tailor-made for the market.

When Virgin pleaded with him yet again to write a love song, Lydon responded to both sides with the same punch: “This is Not a Love Song”, a delicious parody of the song they were asking from him and of the greed underlying those gimmicks called love songs. Paradoxically, it was a hit.

The only fixed member in PiL’s history has been Lydon. Many extraordinary musicians have passed through it. Communication hasn’t always been the best, and there have been clashes of egos. (Lydon’s, needless to say, isn’t small.) His ideal of a band whose members had all an equal place is reflected, though not without dents, in the bold and brilliant music created by PiL in that first period that goes from 1978 to 1993. Throughout, Virgin’s lack of support was a cause of wear and financial disasters. However, with characteristic stubbornness, Lydon managed to keep the project going, fiercely defending his vision.

1993-2015

During PiL’s long hiatus, which started in 1993, Lydon wrote Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs, his first memoirs, centred it seems around the history of the Sex Pistols. He also worked with the electronic duet Leftfield in the superb “Open Up”, and recorded the solo album Psycho’s Path—a somewhat flawed approach to electronic music, though saved by an interesting vocal experimentation in subtle melodic themes.

In 1996 the Sex Pistols got together briefly, with Matlock playing bass again, for the Filthy Lucre tour (that was one of the tabloids’ headlines when the band was fired by EMI in 1977). They were immediately accused of selling out, and of daring to play again, at their age. The media’s attitude towards the Pistols hadn’t changed, even if now the charges were others. Lydon saw it as an opportunity, which had formerly been denied to them, of making a decent tour, and was offended by “the idea that it’s audacious of us to expect to be paid for what we do!”. What wouldn’t change either, in this or in future reunions of the band, would be the animosity among its members. In 2006 they refused to attend the The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s induction ceremony through a hand-written letter sent via fax, insuperably punk in its contempt for the music industry.

However, in the same year the Pistols sold to Universal Music Group the rights of that legacy which Lydon had fought so hard to rescue during an eight-year battle, and their name and image ended up being used for selling a perfume. I haven’t found any interview where Lydon explains why, and I’d really want to know. If ever the Sex Pistols have done something unforgivable, this is it.

For the 2012 Olympic Games in London they were invited to play at the closing ceremony. The idea was to have them go round the track in an open vehicle waving to the crowd, which Lydon thought a pantomime. They refused. However, he felt attracted by film-maker Danny Boyle’s plans for the opening ceremony: a celebration of British culture akin to his own vision. They consented to have a Sex Pistols video projected along with those of other great rock artists, which had a preponderant place in the ceremony, highlighting rock’s importance as the true music of the British people in modern times.

Nevertheless, the Pistols set a condition: that they included a fragment of “God Save the Queen”, and not only the guitar riff. The Olympic committee freaked out. What about using only “God Save”? The Queen would be at the ceremony… The Pistols were firm. “God Save the Queen”, or nothing. The fragment was used at the beginning, when the camera is panning over the Thames, a nod to that boat party so many years behind which had fuelled the witch-hunt against them. Later they showed a fragment of “Pretty Vacant”. Lydon talks about his satisfaction as he watched the ceremony in a hotel room in Poland, finding a Dickensian element in it, and then goes to add, “And there is some possible plausibility in my belief that they [the Royal Family] might actually have enjoyed it. Because that’s what we British are—we’re kind of nuts”.

In 1983 Lydon had appeared along with Harvey Keitel in the film Order of Death, and a decade later he went into TV with the programme Rotten Day. His appearance in I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here in 2004 gained him new attacks. There too he upset things. He decided to quit because of the psychological manipulation of the participants, the cruelty in the eviction system and so on, and did it on the best Rotten style, but his very participation betrays a curious naivete. Breaking the music industry’s rules is worthwhile because it’s a defence of music. But breaking the rules of a reality show? There is nothing there worth the effort. That the money went to a charity doesn’t cancel out the ignoble exploitation of fame that Lydon has denounced so many times. True, he brought humanity, humour and intelligence to the programme, but what for? Might it have been his mania to want to educate us all? At least, though, it opened the door for some nature programmes, which revealed a new sensibility in the enfant terrible.

The attacks he received in 2008 for appearing in the butter advertisement for Country Life were more undeserved. It was that ad what allowed him to reform PiL, dispensing with Virgin and gaining at last his independence from the record industry.

PiL’s new line-up brings back Lu Edmonds (guitar and other string instruments), Bruce Smith (drums), and welcomes Scott Firth (bass). With them, Lydon seems to have found at last his ideal band: friends working together, under the principle of equality.

Their first comeback record, This is PiL (2012), disconcerts in its unevenness. We are also intrigued by Lydon’s transformation as a singer. The unmistakable tremolo he explored after the Pistols gave way to the husky and enormously powerful voice of the 56-year-old man he had become. The album is followed by What The World Needs Now (2015), the band now more strengthened. Some lyrics are preachy, around Lydon’s obsessive themes (everything that’s wrong in the world), and are therefore tiresome, but the more cryptic ones, even if touching on the same subjects, express with beauty and intensity the pain and angst which have been a guiding string in his career. There is also, of course, humour and irony, and it’s not devoid of Rottenesque outbursts, as seen in the potency, which belies the puerility of the paroxysm, with which he sings: “What the world needs now is another fuck off”. Lydon/Rotten is still angry. Whether the lyrics are effective or flawed, and the music exciting or anaemic in these rather lopsided albums, Lydon’s voice holds them up with its vehemence. Lydon and his band are, again, looking for something new, and it hasn’t been in vain, as we can witness in their thrilling live performances.

In 2012 Johnny Rotten was filmed as the guide of a London tourist bus. It’s a delight. Bursting with humour, lucidity and madness all at once, he remembers the London of his youth. It is also a serious criticism of the architectonic destruction of which this city has been the victim during the past few decades, born not only from an absolute indifference towards its history, but from corruption and corporate interests. As he goes into the City, he starts to get really angry. “You fucking wankers! What have you done to London? Cunts!”, he shouts through the microphone. “What’s happened to London? Is there a London anymore? Yuppie bastards! Destroying my country, blokes in suits! Hey, people!, where is London? Does anybody care anymore?” I understand the feeling. Many a time have I felt the same rage myself, on witnessing the destruction of new areas of London. There are times when my eyes well up. I have never reacted like Rotten, but by God, I’d want to.

An energy

Anger is an Energy, the title of Lydon’s autobiography, comes from a line in Rise, a song that makes reference to the torture methods in South Africa during the apartheid, and one of PiL’s greatest hits. The book is fascinating, hilarious, and irritating all at once. It would have benefitted from a good editing job, but we’re already warned in an introductory note that editing Mr. Lydon is no easy thing. Reading it is like being in the kitchen of a friend who won’t stop talking and rambling, whom we put up with because he’s endearing, wise (very, in his own unique way), and very funny. In between bursts of laughter and exasperation, we peer into Lydon’s mind, and he manages something that every author should do, but no one expects from a celebrity’s autobiography: to make us think. It is that head that “Anarchy in the UK” came from, and it was no whim.

The transformation that took place in Lydon/Rotten’s public persona during the years in which his musical career was on hold intrigues me. From being the defiant, arrogant boy who terrified journalists, he came to be a kind of good-natured uncle (though, mind you, still garrulous and loutish), friendly, even affectionate, and he may even get tearful on occasion. He’s hardly recognizable. What happened? He mentions the change in the new generations of journalists: better prepared, more intelligent, with a genuine love for music (those who don’t fulfil these requirements, we must say, are still on the receiving end of lethal outbursts). On finding himself respected at last, Lydon opens up. He shares his enthusiasm about other musicians (many of them as farthest as possible from what we understand as punk, such as Led Zeppelin or the early Bee Gees), which would have been hard to imagine when he annihilated the hit parade’s stars with deathly epithets. Lydon has often made clear that the battle in his public life has been that of asserting his self-respect, demanding the respect of others towards his work and his life, as a human being and not a performing monkey.

Lydon is no longer that sophisticated young man, ostracised in the defence of his integrity. Perhaps it’s the result of now being able to lower his guard, and he seems to be a happier man with PiL’s new incarnation. For years he told us, brazen, that he was simply what he was. We might like it or not, he didn’t care, and he said over and over that he didn’t have to justify himself to anybody. Now we see a man in his sixties who, perhaps to our surprise, does seem to care whether if we like him or not. He doesn’t justify himself, but he does explain: how incredibly painful it was to be so alone and be persecuted (“like a werewolf”, he says in The Filth and The Fury) for so many years just for existing, for having been born poor, for telling the truth, while dragging the physical and emotional consequences of the meningitis. At times he seems paranoid. How to blame him? Throughout his career he has received messages from one nutter or other telling him they want to kill him. And yes, it would be great if his resentment against McLaren and the wound from his story with the Pistols had healed by now, but it is also true that the best he’s done in his career has been born as an expression of his rage.

It does move me to see him show himself vulnerable and explain himself like this, and it frightens me a bit. There is some pathos in seeing this ageing man who was once so defiant, now often overweight and with failing eyesight, showing so publicly that he needs the same that we all humans do: love and respect. But he’s still Johnny Rotten, showing integrity and nobility, and stubborn as a mule. At present he’s the full-time carer of his wife Nora, fourteen years older than him, who suffers from Alzheimer’s. He says he understands her well because he remembers what it was like to lose his memory as a child. He has vehemently expressed his devotion for Nora throughout the forty-one years they’ve been together. He has often said he can’t imagine life without her. Time and again, in his public appearances and interviews in later years, Lydon shows not only his fierceness, which is still there, but his vulnerability. Perhaps lowering his guard like this is his most courageous act of all.

Working Class Hero

John Lydon has contradicted himself and been wrong many times, like everybody—and more if you’re such a bigmouth. To his credit, it must be said that he’s always capable of admitting it. He disarms us when he states that his megalomania comes from the very same place as his omnipresent self-doubt—which is of course always the case, but there are few who recognise it.

To my mind, the greatest rubbish he’s ever said is that he’s going to vote for Trump. At the beginning of the latter’s first campaign Lydon expressed, unequivocally, his alarm at the possibility that such an animal could get into the White House. But, as is the case with Brexit, his opinion has changed. About Brexit, I understand. It’s not as black and white as some believe. His statements regarding Trump have instead provoked in me a real short-circuit. Remembering that, back in Mexico, some people I love dearly are still supporting López Obrador helps me understand, I guess… You don’t know whether to throw your hands up to heaven or collapse in a heap in a corner and burst into tears, but it is helpful to bear in mind that political opinions do not make someone atrocious per se.

Lydon has some obsessions: his despise for politicians, for religion, for Britain’s social and political system, for the middle class, and his pride of coming from the working class. The documentary The Filth and the Fury starts with his voice in off over scenes of a collapsed England, talking about his disappointment of the Labour party, which time and again has betrayed the working class (he’s right). There is, though, in his admirable pride about his origins a blind spot that his support for Trump makes manifest. Though he admits that there is much in Trump that he doesn’t like, he sustains that he’s the only one who has a viable economic plan to put money in the pockets of the poorest. It’s the blind spot that has made millions of people in recent years take to power populist governments of every persuasion led by megalomaniac sociopaths.

Until quite recently, I had watched the phenomenon in horror, but from a kind of purist balcony, so to speak, convinced that I’d never hear of any friend or person I admire capable of supporting Trump. Lydon’s statements—and, as you’ll have seen, he’s one of my great heroes—knocked me down the balcony, and the bruise really hurts. Once floored, it was my turn to do some soul-searching. I’ll explain:

I’ve already said that sometimes I find Lydon irritating. If I ask myself why, I must confess that it is, partly, because of his English working-class mannerisms. And that’s something I really don’t want to see. I’ve tried to get away by saying that this isn’t my culture, that I come from somewhere else and that I understand indeed all the different classes in the country I come from, which is Mexico. But it’s a poor excuse. I find some things irritating in Lydon because of my class prejudices, and there’s no way to conceal it. Going back to Dickens (an author, by the way, dear to Lydon), I’ve suddenly found myself like Pip in Great Expectations, embarrassed to discover that his benefactor is Magwitch, and fully aware of deserving the pain of the mutual disappointment.

I come from what I guess we could call the Mexican upper middle-class. True, when I left my parents’ home at 19, I came down many rungs in the social ladder, and that’s where I’ve remained all my life, hardly ever reaching the minimum wage. Like many authors and artists, I’ve become déclasée. But some worldviews, prejudices included, of our upbringing are difficult to shake off. Some years ago, I lived in Finsbury Park, where Lydon grew up in poverty. I was poor too, renting a room in a horrid house, but the neighbourhood was now as gentrified as most of London. I often complain about gentrification, but I’m a hypocrite, because I do prefer the new cafés. When I lived there and there was an Arsenal match in the stadium nearby, I hated the shouting and beer-drinking hordes that swamped the streets. In his youth, John Lydon was one of those football supporters.

In turn, Lydon’s prejudices aren’t smaller. Since he was very young, he ranted against the middle class and the hippies, who to his mind weren’t true rebels. I think I wasn’t a hippie only because I was born a bit late, but I picked up something when I was younger, and I’d like to remind Lydon that we all have a right to want to change the world, mistakes and all; not only the working class, and that, as he has said many times, even when talking about Queen Elizabeth II, where we are born is not our fault.

In his recent statements about Trump, Lydon has said a lot of nonsense mixed with some truths. He talks, for example, about his mistrust (which I share) of some tendencies in the left espousing an increasingly totalitarian and smug ideology, which includes the excesses of political correctness, but then he gets all mixed up. What is tragic and utterly sad is that, because of his own ideology, he will vote for a man who represents the absolute opposite of the human person that Lydon has proved to be for decades. But, as some have already said in his defence, it is his democratic right to vote for whoever he wants, even if those of us who admire him are broken-hearted.

Many times John Lydon has said that there should be no division of classes or race. It’s a pity that this musician who’s particularly interested in the social and political aspects of culture can’t see that prejudices come from all sides of the social spectrum. His contempt for the middle class (which, by the way, makes for a great deal of his audience) touches the limits of rationality, and I suspect it bears on his vote’s decision. That’s what I think, even if I say so with my tail between my legs, once acknowledged my own prejudices against the working class of the country I’ve been living in for the past 21 years. We’re all such idiots.

And thank you

When I started writing these notes, I didn’t know that Lydon was about to publish a new book, I May be Wrong, I May be Right, let alone that he was going to vote for Trump. I haven’t read the book. I may not get to do so. To start with, it is an expensive limited edition. Then again, I suspect that there will be there several things I’ve already read in his second book. In his verbal and written expression, as opposed to what happens with his music, Lydon tends to repeat himself. But most of all, I don’t know if in the said book he talks about the Trump issue, and the advent of winter in the midst of the pandemic’s second wave looks grim enough as to make myself even sadder.

I started writing about Rotten/Lydon after several weeks of feeling very low, on the way to depression, not only because of the pandemic, but because of a pervading sense of defeat, exhausted by the innumerable wars you have to fight in this world to survive as a writer. Dejected, I couldn’t do any progress in the writing of my new novel, and writer’s block was killing me. In a moment of lucidity, I realised that my depression was nothing but rage, with no apparent means of release. And then I remembered “Rise”, the single PiL launched a few days after Lydon won the legal case against McLaren, and its famous line, “anger is an energy”. Lydon has always known it to be so; it is the energy behind his music, and what shook him out of the crippling effects of meningitis: back then the doctors advised his parents to be tough with him, so that anger forced him to fight, and recover. I looked for Rise’s video; I listened again to PiL and, on the spur of it, to the Sex Pistols. Depression vanished, and so did writer’s block. I’ve gone back to my novel with an energy that I hadn’t had for a very long time.

We want our heroes forever young, beautiful, and pure. Johnny Rotten was all that, indelibly captured in that young man on his knees onstage in Winterland, San Francisco, in January 1978, all the depth of his insight and his disenchantment in his eyes, before putting down the microphone and taking his leave of the circus the Sex Pistols had become. We don’t like them getting old; let alone them being human and making mistakes, and in the case of rock stars, our atavistic proclivity to crucifying seems to be particularly gory.

I’d wish with all my heart that Lydon didn’t support Trump. I would have also liked that Rimbaud hadn’t ended up selling weapons and turning his back on poetry. But human life isn’t like that, tailored to our illusions, and the life of others even less so. John Lydon may be wrong in his recent political opinions and in many other things; that’s his problem, but what we as an audience should care about is the fact that, for nearly half a century, he has generously invited us, with exemplary courage, steadfastness and obstinacy, to a land in which all divisions of class and race are effectively abolished: the music.

Surely there will be some now who will send him new death threats. I, sad and all, leave you instead with the “Rise” video, and keep on saying: thank you, Johnny Rotten.

Origen

Es un genuino héroe dickensiano. Hijo de inmigrantes irlandeses, crece en la pobreza en el norte de Londres. A los siete años contrae meningitis contagiado por las ratas en el patio de su casa, cae en un coma de meses y cuando despierta ha perdido la memoria. Al salir del hospital vuelve a casa sin otra alternativa que creer que el señor y la señora que dicen ser sus padres lo son de verdad. Recuperar la memoria le lleva cuatro años; eso, y las muchas secuelas de la enfermedad, lo vuelven tímido y solitario. Su refugio es la biblioteca pública. Se ha retrasado en la escuela, donde enfrenta el rechazo de otros niños que lo encuentran raro. Su aguda inteligencia y su amor por los libros, unidos a cierto talento para la comedia, le ganan finalmente la aceptación de sus compañeros, sobre todo cuando usa sus talentos para desafiar a los maestros, de quienes no cree estar recibiendo educación alguna. El infortunio no le impide asumir su responsabilidad de hijo mayor, y pasa la infancia cuidando a sus tres hermanos. A veces, también, a su madre enfermiza, propensa a los abortos espontáneos. Es niño de barrio y, aunque retraído y frágil, no le saca a los madrazos cuando hace falta.

Para pagarse sus estudios superiores y contribuir a la economía de su casa trabaja como albañil. Es grande su avidez por aprenderlo todo, en especial literatura e historia. Su retraimiento se convierte en la férrea voluntad de ser un individuo. Ya adolescente se pinta el pelo de verde, y su padre lo corre de la casa porque parece una col de Bruselas. Estar en el paro lo deprime: sabe que es su derecho, pero lo violenta la humillación que se le inflige a la gente que no tiene más opciones. Trabaja entonces en una fábrica de zapatos, y también en un centro asistencial para niños “con problemas”: le encanta jugar con ellos, enseñarles a hacer aviones de madera, aunque sus empleadores lo vean con recelo por su aspecto estrafalario. Después será empleado de limpieza en el restaurante de una tienda de departamentos junto a uno de sus mejores amigos, quien aparecerá después, trágicamente, en esta historia.

A finales de la década de 1970 se le ve a menudo entre los jóvenes desafectos que frecuentan King’s Road, en el barrio de Chelsea, cuando Inglaterra, levantándose lenta y penosamente de la posguerra, se desmorona por la división de clases, la pobreza de muchos, los continuos disturbios y la brutalidad policiaca. Ejemplar de la picaresca urbana, vendiendo anfetaminas porque no alcanza el dinero, es bien consciente de vivir en un sistema que deja muy pocas opciones fuera de la criminalidad para chicos como él.

Pero el crimen no es lo suyo. Lo que él quiere es igualdad, y el imperio de la verdad: un mundo que despierte, o que estalle si no. Llama la atención por su actitud retadora y distante a la vez, reflejada en su manera de vestir: a los 19 años se le ve con una camiseta agujereada de Pink Floyd, en la que ha escrito I hate arriba del nombre de la banda. Malcolm McLaren, retorcido personaje de la contracultura londinense y dueño, junto a la diseñadora Vivienne Westwood, de una boutique llamada Sex, le invita a una audición como cantante para un grupo de rock al que representa. Aunque amante de la música desde niño (siempre ha sido el DJ en las fiestas familiares), nuestro héroe nunca ha cantado. En la escuela católica a que asistía se había esforzado por no aprender a cantar, para no atraer la peligrosa atención de los sacerdotes. Sin embargo, hace la audición: un cover de una canción de Alice Cooper. El arrojo y la furia de su interpretación le aseguran el trabajo.

La figura ya encorvada por la meningitis, el dolor y mareos que lo obligan a encorvarse aún más, la mirada desorbitada con que trata de enfocar la vista debilitada también por la enfermedad, son todos elementos que utiliza a su favor para crear una presencia en el escenario que niega todas las convenciones del rock star y subraya el carácter incendiario de las letras de las canciones que escribe. Tiene diecinueve años.

El salto súbito a la infamia vendrá cargado de tribulaciones, pero dará la pelea, se ganará el respeto que es su derecho y terminará adorado por millones de personas, convertido en una especie de tesoro nacional. Algún día declarará: “yo vengo del basurero”, y le agradecerá al sistema de bibliotecas públicas haberle enseñado, durante las horas solitarias de su infancia, a aprender a utilizar las palabras como granadas contra el sistema político y social de un país que, para cuando llegó a los veintiún años, ya lo había querido linchar.

Sex Pistols

La historia del rock está sembrada de jóvenes cadáveres. Que Johnny Rotten no haya sido uno de ellos es asombroso, y no tanto porque no haya sucumbido a la tríada de sex and drugs and rock ’n roll, sino por haber sobrevivido a la persecución pública contra los Sex Pistols, a la vez que al ostracismo impuesto por sus compañeros en la banda y las humillaciones a manos de su abyecto mánager, por no hablar de las agresiones de que fue objeto al dejar a los Pistols, provenientes tanto de la prensa como de un movimiento punk esclerotizado que no había entendido nada de nada (pero es que ni el resto de los Sex Pistols pareció entender nada nunca). Si la estimación ganada a pulso de John Lydon (el nombre con que nació) sobrevivirá a sus recientes declaraciones de que votará por Trump, ahora que es ciudadano de Estados Unidos, es tema que tocaré más adelante.

La historia de los Sex Pistols ha sido contada muchas veces, desde distintas perspectivas. Yo la creo como la cuenta Lydon, porque la evidencia está por todas partes. Basta con echar un ojo a entrevistas posteriores con cualquiera de los actores del drama, a la infame película The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle (1980), dirigida por Julien Temple e instigada por McLaren (aunque, hay que decirlo, hace falta estómago para soportarla), o a The Filth and the Fury (2000), documental dirigido también, esquizofrénicamente, por Temple, para comprobarlo: McLaren y los otros Pistols se incriminan solos. Deleznable, siniestro a punta de pura banalidad y mediocridad, hay sin embargo que reconocerle a McLaren, ya que empezamos estas páginas mencionando a Dickens, que alcanzó con creces su anhelada estatura de villano novelesco.

Los Sex Pistols eran Steve Jones en la guitarra, Paul Cook en la batería, Glen Matlock en el bajo y Rotten en la voz, además de escribir las letras de las canciones. En 1977 Matlock fue reemplazado por Sid Vicious. Sabemos que los Sex Pistols fueron un estallido que revolucionó al rock, sacándolo de su complacencia, y cuya violencia le puso enfrente un espejo a una sociedad corrompida.

Estas notas se concentran no en ellos, sino en la figura de Lydon, alias Rotten; en su inteligencia feroz, en su integridad artística y su pasmosa capacidad de resistencia, pero ahí es por donde hay que empezar. El resentimiento entre los exintegrantes de los Sex Pistols probablemente no se resuelva nunca: estuvo ahí desde el principio. Johnny Rotten llegó a la banda cuando ya estaba formada, con mánager incluido, y resultó que los opacaría a todos. Con sus letras sediciosas y fiereza en el escenario convertiría a un grupo de muchachos talentosos, pero sin dirección, en la banda de rock más famosa (o infame) del mundo en su momento.

Rotten cargaba en su arsenal armas singulares: su estudio atento de Shakespeare (quien en su opinión tendría que representarse con la voz del pueblo, y no adecentado por Oxford y Cambridge) era una de ellas. Otras eran su pasión por la oratoria y por la historia, el deleite que encontraba en la tradición de la comedia inglesa, y la espina clavada de la falta de oportunidades para la clase trabajadora. No era, como la prensa pretendería muy pronto, un delincuente nihilista. Quería, para usar la expresión manida, superarse, aunque no sabía cómo ni si era posible, y estaba, eso sí, lleno de rabia. Las armas a su alcance eran facultades que había cultivado, y todas se conjugan de manera explosiva en el nacimiento de Johnny Rotten, Sex Pistol. Arden, gloriosamente, en ese grito de furia, desesperación y desafío que es “Anarchy in the UK”: en la teatralidad como vehículo de emoción visceral; en el rodar de las erres, la distorsión de las vocales, el chasquido al final de las frases dislocadas; en el cuerpo como un látigo fustigando las palabras iracundas, demostrando que la fuerza de una canción es más que la mera combinación de letra y música.

McLaren era mediocre y maligno, pero no era tonto, y aquilató las virtudes de Rotten como líder del grupo desde el principio. Sin embargo, gustaba hablar de sus primeras impresiones de él como “el jorobado de Notre Dame”, y en The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle lo describiría en “una actitud que lo hacía parecer tullido, algo vulnerable. Y eso me gustó”. Era parte del “barro” que, según su fantasía, él había moldeado; uno de los seres humanos que había manipulado para escandalizar y tomarle el pelo a todo el mundo mientras se forraba los bolsillos. En The Filth and the Fury, que les da a los exintegrantes de la banda la oportunidad de contar su versión de la historia, Lydon encuentra en cambio una manera inteligente y luminosa de apreciar su vulnerabilidad, al hablar de cómo el personaje de Ricardo Tercero le había ayudado al ingresar a los Sex Pistols: “deforme, chistoso, grotesco, y luego el jorobado de Notre Dame está ahí, todos estos personajes estrafalarios, pero que de alguna forma, pese a todas sus deformidades, se las ingeniaban para lograr algo.”

Lydon encontraba absurda a la gente que paseaba al último grito de la moda por King’s Road, sin enterarse de que Inglaterra se estaba cayendo a pedazos. A McLaren no le habría pasado inadvertida su mirada burlona sobre la nueva veta sadomasoquista en la mercancía de su boutique, y el espectáculo de la gente que tenía que someterse a las incomodidades de ese atuendo para poder tener sexo porque era “incapaz de enfrentar la realidad”. Tampoco habría podido ignorar que ese muchacho no era barro moldeable, y que no obedecía órdenes de nadie. Su estrategia fue entonces la de divide y vencerás, asegurándose de que la exclusión de Rotten fuera completa. No era invitado a las fiestas con el resto del grupo; mientras que a los otros integrantes de los Pistols McLaren les conseguía casa, Rotten seguía yendo de un lado a otro porque no tenía dónde vivir. Aquí habría que recordar que los Sex Pistols, fenómeno mundial en el mundo del rock durante su breve historia, no tenían dinero. McLaren les pagaba una miseria por tocada, de las que había pocas, y el resto se lo embolsaba él o lo invertía en sus propios proyectos, incluyendo sus pésimas películas, con las que ansiaba explotar la fama de la banda.

Manipular a los otros Pistols no fue difícil. Para ellos también Rotten era “distinto”, “difícil”. “Era el intelectual”, diría después Steve Jones. En su defensa habrá que recordar lo jóvenes que eran todos, y las duras circunstancias de las que provenían, Jones en particular: los Sex Pistols eran lo único que tenía. Su única otra opción habría sido la delincuencia.

Cuando Matlock se sale de la banda, Rotten comete el error de invitar a su amigo John Simon Ritchie (a quien había rebautizado como Sid Vicious en honor a su hámster) a reemplazarlo. Vicious no sabía tocar el bajo, pero era el fan número uno. Rotten pensó que sería un aliado que volvería soportable su aislamiento, pero las cosas no funcionaron así. Vicious, hijo de una adicta que le daba heroína como regalo de cumpleaños, era quizá el más frágil de todos. La fama súbita, su relación con la groupie Nancy Spungen y las tácticas de división de McLaren lo llevaron a una espiral de autodestrucción que, como es bien sabido, culminaría en el asesinato de Spungen, del cual se le acusó (aunque el caso sigue inconcluso y nunca fue suficientemente investigado), y en la sobredosis de heroína que terminó con su vida a los 21 años.

Entre su ingreso a los Sex Pistols y su muerte, Vicious hizo honor a su nombre. Quería ser el más rudo de todos; respondía con violencia a las provocaciones del público, y el bajo que no sabía tocar le pareció alguna vez un arma efectiva; competía con Rotten en el escenario para demostrar quién era el “verdadero” punk. Hay videos perturbadores que lo muestran tocando lleno de sangre, producto de la automutilación o de algún pleito. McLaren, engolosinado con el creciente caos, lo azuzaba. Johnny Rotten seguía solo, ahora asqueado por el comportamiento de su amigo y por la distorsión de la música que hacían, convertida en una bufonada.

Desde esta distancia, es difícil entender que la sociedad haya tenido un colapso nervioso por las correrías de cuatro jovencitos, uno apodado Johnny Rotten por el estado de sus dientes, el otro Sid Vicious gracias a un hámster. Sin duda, los medios amarillistas fueron más responsables que los Pistols mismos, quienes asaltaron la conciencia nacional en la entrevista que les hiciera Bill Grundy para el programa Today de Thames Television en diciembre del 76 (cuando Matlock aún era el bajista). Grundy estaba tan borracho como los entrevistados, y evidentemente decidido a provocarlos. Tras aguijonearlos, con éxito considerable, para que dijeran palabrotas en un programa en vivo, los Sex Pistols se convierten en la encarnación de la amenaza a la moral nacional. Los titulares de los tabloides al día siguiente harían pensar que la prensa no tenía problemas más serios de qué ocuparse; The Filth and The Fury es uno de los más memorables.

Hubo protestas callejeras (una francamente estrambótica, con los manifestantes cantando villancicos). Se cancelaron la mayoría de los conciertos de la banda, que terminó recurriendo a seudónimos para ser contratada, como S.P.O.T.S. (Sex Pistols On Tour Secretly). EMI, con quien acababan de firmar contrato, los despidió. Cierto, los chicos eran unos malcriados, pero el pánico desatado era pura histeria colectiva. O un circo mediático, que viene a ser lo mismo. Cuando el concejal de Londres Bernard Brook Partridge declaró en la televisión que las bandas punk mejorarían muchísimo mediante la muerte súbita, que los Sex Pistols eran “increíblemente nauseabundos”, “la antítesis de la humanidad”, y que le gustaría “ver a alguien cavar un agujero muy, muy grande y extremadamente profundo, y arrojar dentro a toda la maldita caterva”, pues “el mundo entero mejoraría muchísimo con su total y absoluta falta de existencia”, espero que habrá habido quién se preguntara de qué bando provenía el mayor grado de violencia.

God Save the Queen, una navidad y el final