Flying High

Jorge Iglesias

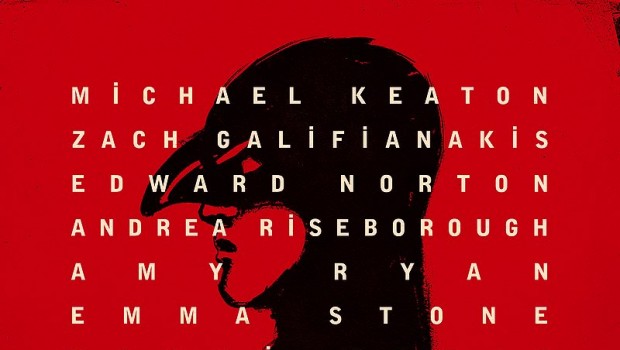

Birdman

Dir. Alejandro González Iñárritu

USA, 2014

The stuff of superhero movies—a fireball flies through the sky, apparently falling. Cut to a room where a man in briefs gives his back to the viewer, his body in the lotus position… suspended in midair. The film bears the signature of Alejandro González Iñárritu, but we know from the beginning this will be neither another Amores Perros (2000), nor another Babel (2006). The realism of the Mexican cineaste’s first films was complemented by a touch of narrative impressionism in Biutiful (2010). In his latest feature, Birdman: or The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance, Iñárritu leads us deep into the mind of a troubled professional, reaching in the process new heights in the art of poetic filmmaking.

Michael Keaton delivers one of the most memorable performances of his career as Riggan Thomson, an actor who has seen better days. Having once enjoyed success as the man inside the Birdman suit, he now attempts to achieve “serious” acclaim with a stage adaptation of Raymond Carver’s “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” In order to reach this goal, he must please not only his potential audience and critics, but also his manager, Jake (Zack Galifianakis), his antagonist, Mike (Edward Norton), his partner, Laura (Andrea Riseborough), his ex-wife, Sylvia (Amy Ryan), and his daughter, Sam (Emma Stone). Riggan’s plight is that of the typecast celebrity seeking to transcend his persona. Throughout the film, he hears the voice of Birdman, who tries to tempt him into going back to the commercial series that made him famous, to abandon his theatre project. Although Keaton has stated that he is quite unlike Riggan, the fact that he is most commonly associated with Batman lends effectiveness to his role in Birdman. There is a side to Riggan that everyone has seen, but he wishes to show another side of himself, which may be the reason why the film begins by showing us his back. When following Riggan’s back through the corridors of the theatre towards the stage, viewers might be reminded of The Wrestler (Darren Aronofsky, 2008), a film with which Birdman bears comparison. Like Mickey Rourke’s character in Aronofsky’s film—who is also a faded professional striving to reclaim the spotlight—Riggan juggles his professional and personal obligations, often failing, but always persisting in the face of adversity. If Biutiful represents the struggle of an ordinary man, Birdman portrays the struggle of the artist. Riggan joins the company of Aronofsky’s wrestler and of his black swan as professionals who become aware that their art demands the greatest of sacrifices.

The performances of Edward Norton and Emma Stone are also worthy of praise. Norton plays an actor who might save or sink Riggan’s theatre production. Whether his character, Mike, is with Riggan or against him is not clear. Norton embodies an energy and defiance that clash with Riggan’s ambition. Their exchange typifies the ambiguous relationship that can develop between those who share a stage, the equilibrium of which is crucial for the performance’s success. Stone, on her part, is excellently cast as the youngster just out of rehab. Cynical, fragile, and potentially dangerous, Sam is another human being in need of attention and affection. She is pure emotion and frankness when she tries to bring her father down to Earth, telling him that he is not important, in one of the most effective scenes in the film. Having recently worked with Woody Allen (Magic in the Moonlight, 2014), Emma Stone continues to establish herself as a serious, versatile actress not to be typecast.

From the technical perspective, Birdman can only be described as a work of genius. The cinematography is flawless, elegant, so it is no surprise that the artist in charge is Emmanuel Lubezki, who received an Academy Award for his masterful work in Gravity (2013), and who has joined forces with such renowned directors as Alfonso Cuarón, Terrence Malick, and the Coen brothers. Birdman follows the footsteps of Hitchcock’s Rope (1948): except for one crucial cut that the spectator should look out for, we get the feeling that we are watching one long continuous take. The challenge that this represents for the cast and crew is as considerable given the danger that the film might seem pretentious. It is a choice, however, that points to the impressionistic or psychological nature of the film. Time is not chronological, and even though rehearsals, previews, and the opening night of Riggan’s play occur within the same take, the action obviously spans several days. The long take effect gives continuity to Riggan’s life and draws the viewer in it. After all, most of the action takes place, appropriately, in a theatre, where there are no cuts and actors have only one chance to get each performance right.

Perhaps the greatest advantage of focusing on the character of an actor is the opportunity to comment on the art form that is most closely connected to the cinema. If in previous Iñárritu films the critique was social, in Birdman, it is both social and artistic. One of the most daring moments of the film takes place when we are suddenly shown, in pastiche fashion, an explosive, special-effects-ridden scene worthy of any commercial superhero movie. People scream and cars are blown up as Birdman fights an enormous metallic bird. “This is where the money is,” says Birdman’s voice in Riggan’s mind, “this is what people want.” While Riggan’s play threatens to be a failure, an accidental video of him running in his underwear through the streets of New York goes viral as soon as it is posted on the Internet. Postmodernism blurred the line between “art” and “popular culture,” but has the line disappeared altogether? Christopher Nolan and Alfonso Cuarón have proved that it is possible to produce “films” and “movies” with equal success. Guillermo Del Toro, for his part, provides a great example with Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) that a film can appeal to both general audiences and sophisticated cinephiles. For celebrities torn between devoting themselves to Art, or selling out, the dilemma remains.

Finally, a word about the film’s use of poetic imagery. When Charlie Rose interviewed Del Toro, Iñárritu, and Cuarón, Del Toro expressed his desire to see a fantasy film by Iñárritu, who until then had directed three realistic feature films. Though still realistic, his following effort, Biutiful, incorporated psychological imagery, such as the scene in which Uxbal gets a glimpse of himself attached to the ceiling. Birdman constitutes a further advance into that poetic territory. Riggan appears to have telekinetic powers, and in one Felliniesque moment he levitates and begins to fly. These are not instances of magic realism, but part of the film’s narrative impressionism: the audience is allowed to see Riggan as he sees himself. Like Guido of 8½ (Federico Fellini, 1963) and the protagonist of Brazil (Terry Gilliam, 1985), Riggan wishes to rise above the complications of everyday life. In order to get recognition in the era of the hyperreal—when everything has been seen, when audiences have become desensitized—it might be necessary to transcend the law of gravity.

Birdman may well be Iñárritu’s most ambitious work to date. His filmography reveals a brilliant mind that seeks to amaze through narrative complexity, technical virtuosity, and visual exuberance. The crossed paths and multiple perspectives of Amores Perros and Babel have given way to character studies in Biutiful and Birdman. Iñárritu succeeds in both the panoramic and the focused approach, and his determination to reach a higher mark with every effort has earned him the worldwide recognition he deserves. Birdman is a work of art that soars and stuns. Balancing realism and impressionism, prose and poetry, this film flies high without burning its wings.

Posted: January 12, 2015 at 6:28 pm