The Meaning of Acceptance: Freedom of Speech After the Charlie Hebdo Massacre

Saúl Sosnowski / Tanya Huntington

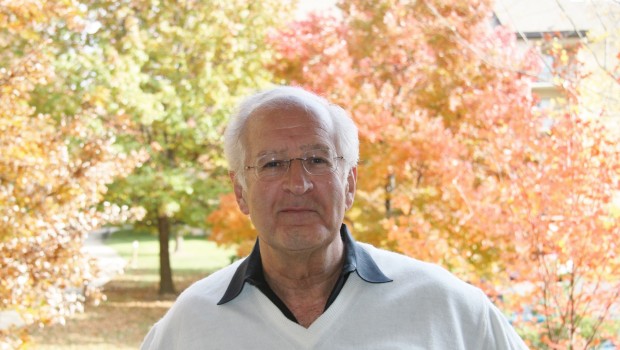

Literal spoke to Hispamérica editor and expert in conflict resolution Dr. Saúl Sosnowski about the importance of safeguarding journalists and civil society from extremist violence. He is Professor of Latin American literature and Senior Faculty Advisor for International Initiatives at the University of Maryland, College Park, where for over a decade he directed the Office of International Programs, after having chaired the Department of Spanish and Portuguese for twenty years. He organized and coordinated multiple conferences on the repression of culture and re-democratization in the Southern Cone and co-directed a civil society conflict resolution initiative after the last war between Ecuador and Peru. In 1995 he launched the project “A Culture for Democracy in Latin America,” and in March 2001, in Buenos Aires, “New Leadership for a Democratic Society.” Founder and editor of Hispamérica, a scholarly journal dedicated for over forty years to publishing Latin American literature and literary criticism, his lectures and publications for over a decade have centered on issues of civil education, democracy and conflict management, and cultural politics with a focus on Latin America.

***

First of all, Saúl, thank you for accepting this interview. Having worked for you myself, I know that free speech is a topic you cherish. It struck me that, given your multifaceted career, your feelings regarding the recent tragedy at the headquarters of Charlie Hebdo in Paris may very well be more complex than the sort of gut reaction many of us feel. Is this the case?

I’m sure we share the same ‘gut reaction’ when faced (again!), with acts that defy comprehension and are devoid of any justification. This was an egregious attack by intolerant fanatics on values we hold dear; an attack on freedom of expression and on the right to live and freely practice, or not, any religion. This tragedy hit a collective nerve that expanded beyond Charlie Hebdo. In addition to its staff, four Jews were murdered at a kosher market and a Moslem policeman was cut down. Nations that have grown and developed a certain way of life are being reminded of the meaning of acceptance, of the price of coexistence. The reaction of those who understand it has been evident over the last few days. And so have the cynicism, bigotry, and shameless silence of those who should have come out in the front line.

As an editor, what has been your experience in working with authors who have been persecuted for texts they have published? Are there any anecdotes you can share with us?

In Hispamérica, and in the volumes that gathered testimonial presentations at conferences we held in Maryland, Argentina, and Chile, I published a number of texts by exiled writers, and also by some who later disappeared during the military regimes that ruled Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay in the 1970s and 80s. Rather than offer anecdotes, and given the context of this interview, I would underscore the noticeable difference between those who wrote while under repressive regimes—seeking allegorical references, addressing, for instance, the foundational period of the nation to speak of their own time, uttering views in muted tones—vis-à-vis those who were able to speak freely in their various sites in exile.

And as an expert in conflict resolution, have you encountered instances where free speech is wielded as a weapon that exacerbates our cultural differences?

Free speech is a right, a privilege, a major defining achievement of a free society. Differences are integral to the cultural tapestry that defines and enriches us. I find nothing wrong in underscoring those differences, whether it is through the seemingly ‘politically correct’ modus operandi of some societies, or through the most acerbic, acid humor that constitutes a satirical discourse.

If the subtext of your question hints at whether free speech can go too far, the answer is: never to the point that would justify the violation of the rule of law, and certainly not the mutilations nor the murderous acts that are defining a growing number of intolerant religious factions and existing or self-proclaimed states.

As you are no doubt aware, here in Mexico we have endured for some time an intolerable degree of violence against journalists. Do you see any parallels between the situation in Europe and here in the Americas?

Attacks on free speech, on investigative journalism, on revelations of corruption and other criminal acts by governments or individuals, do not have geographical boundaries. And, unfortunately, these attacks continue to take place under democratically elected governments that purportedly support freedom of the press.

Moreover, the DNA of authoritarian mindsets does not record a sense of humor. This is particularly the case when humor, whether tame or aggressive, probes and cuts to the core tenets of seemingly divine claims to universal truths. Intolerance precludes doubt and covers both political and religious figures that lord over their flocks.

Would you define what is going on as a clash of cultural and religious identity, or as more of a political issue?

We can certainly intertwine all these factors. History, and our own time, shows examples of coexistence; history also shows the unrelenting destruction of ‘others’ by powers that hold themselves to be the sole possessors of ‘the truth,’ whether religious or political. Need we recall as examples what happened, for instance, in Spain beginning in 1492, or at varying scales of horror, in Hitler’s Germany, or in Stalin’s Soviet Union, or in more recent theocracies?

And finally, how do you see the panorama unfolding in the near future?

The immediate outlook is rather bleak, unless unified, concerted, transnational legal efforts are undertaken to confront criminal intolerance, regardless of its source and unfurled cause. The future of a society grounded on the rule of law and free of coercion is at stake.

Tanya Huntington is a contributing writer at Literal. Follow her on Twitter at @TanyaHuntington

Posted: January 14, 2015 at 10:22 pm

Perhaps it is more difficult to accept freedom of speech when a religious cause intervenes