A Christmas Tale

Cuento de Navidad

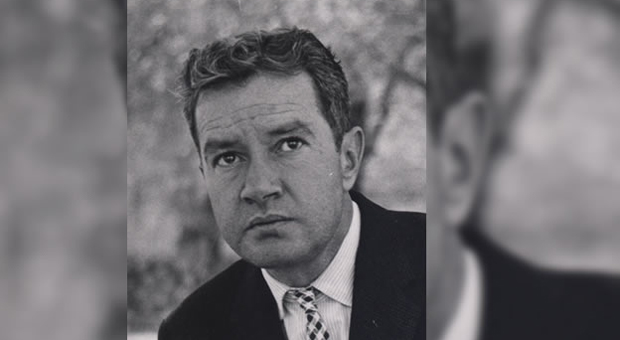

Ernesto Hernández Busto

English translation by Tanya Huntington

It had been snowing heavily for several days, but both my friends were adamant that we reach a village lost somewhere in the Alps. Our favorite pastime was making fun of L., whose obsession with snow kept him glued to the window. A. and I huddled together and teased him in between trying to get some sleep. We had been on the train for more than twelve hours, heading towards Tolmezzo in the middle of Carnia, when we hit a half-meter of snow in Gemona. The rails were blocked, so we had to deboard, get on another train and backtrack to a nearby city. Typical twenty-somethings, we were traveling penniless. And then L. came up with an idea: a friend of a friend of his knew someone in Udine. With any luck, we could make some calls and find a roof to stay under while we waited it out.

That “someone” ended up being two people; they bore a certain likeness, although they did not treat one another like sisters. Any resemblance was owed to their hair, which was unusually long and shiny and perhaps the only clean thing about those two ladies, with their long nails and bitter faces. A. tried to be gallant, praising their blonde manes which fell past their waists, and in between smiles one of them shared their secret: birth control pills, pulverized and dissolved in shampoo. “Actually, a Cuban friend taught us.” There was nothing attractive about their disheveled bodies and hawk-like profiles, and even less about the foul-smelling, colorful rags they were swaddled in.

That first night, L. and I offered to go get something to eat: some pizzas. Outside it kept on snowing and as we walked to the trattoria, I had to endure his sexual fantasies: “A threesome, bro, it’s a done deal, you’ll see.” I retorted my concerns about hygiene and some suspicions regarding his pansexual vision; if they weren’t sisters or cousins, those girls were a couple, and we should already be grateful for not having to spend the night at the station. It just wasn’t worth posing as a couple of Don Juans and taking an unnecessary risk.

We stayed for three days as though it were the most natural thing in the world. Each night, we’d feed those off-kilter blondes, who would immediately devour everything, including what was on our own plates. They explained how they barely had enough money to eat, how they usually sustained themselves on whatever they could steal from the insane asylum where they worked on the weekends.

Of what one might call actual conversation, there was almost none. Our Italian didn’t help, either. We felt at ease sharing lodging and meals, but we didn’t dare risk any further information. The curse of politics was everywhere: the struggle of exiles, the thought that those hippie girls sympathized with “all that” we had just left behind. Then there was the poster: under the gigantic semblance and watchful, wall-eyed stare of the Guerrillero, we learned to get by using our sleeping bags to compensate for the lack of warmth. One small misstep, and we might have to sleep out on the street. Our hosts had already displayed tempestuous personalities. In broken English, they had spoken with A. of love; they’d once shared a boyfriend, but later on had grown tired of men. “It’s like a postcard, you know,” one said. “When you still love but you’re not in love. You simply preserve a piece of the past that you cannot change, like a postcard. With affection, as the Americans say. With men, I can no longer get past that point.” A. made several attempts to explore other angles, but the discussion later turned to Cuban matters and we all began to sour. I don’t remember all the details from that evening, but I do recall it ended with far too much vehemence, long faces, and A. drowning in the bottle of cheap rum we carried in our backpack. It seemed as if any sign of virility would be an affront to those filthy women’s quarters, where memories hardened and logic was reduced to four or five clichés from leftist manuals.

On the last day, they kindly escorted us to the station. Service had resumed, even though it continued to snow. I mentioned Jason, the American who supposedly knew L., whose friend in turn had also stayed with the Blondes. Even now, the details were vague; after a few phone calls L. had dropped several names and very eloquently convinced them of our desperate situation. Now, post-urgency, he attempted to tie up loose ends with them. “But Jason has never been in Cuba,” one of them said. “What Jason are you talking about?” And then, right there on the platform, we realized our misunderstanding. It was all a mistake, we had been the guests of total strangers. An eerie discomfort began to spread; it was embarrassing to discover that our mutual friend didn’t even exist, that it had all been a game of chance, a coincidence. The sense of bonding that our farewell had kindled was extinguished instantly. They must have felt betrayed. Without any further ado, we hastily said our goodbyes. As I rearranged my dirty clothes in my backpack, I couldn’t help wondering whether the whole thing had just been wishful thinking. Three travelers in pursuit of a dubious mirage.

Ernesto Hernández Busto (La Habana, Cuba, 1968). Cuban poet, essayist, editor and translator resides in Barcelona. He is the author of Perfiles derechos. Fisonomías del escritor reaccionario (Península, Barcelona, 2004) and Inventario de saldos. Apuntes sobre literatura cubana (Colibrí, Madrid, 2005). He is a collaborator of El País.

Ernesto Hernández Busto (La Habana, Cuba, 1968). Cuban poet, essayist, editor and translator resides in Barcelona. He is the author of Perfiles derechos. Fisonomías del escritor reaccionario (Península, Barcelona, 2004) and Inventario de saldos. Apuntes sobre literatura cubana (Colibrí, Madrid, 2005). He is a collaborator of El País.

©Literal Publishing

Nevaba fuerte desde hacía varios días, pero mis dos amigos estaban empeñados en que conseguiríamos llegar a aquel pueblo perdido en medio de los Alpes. Nuestro entretenimiento favorito era burlarnos de L., con aquella obsesión tropical por la nieve que lo mantenía imantado a la ventanilla del tren, mientras A. y yo, arrebujados y maledicentes, intentábamos dormir un poco. Llevábamos más de doce horas en aquel vagón hacia Tolmezzo, en medio de la Carnia. Pero en Gemona nos encontramos medio metro de nieve. El tren se bloqueó, tuvimos que bajar, tomar otro, retroceder hasta una ciudad cercana. Viajábamos casi sin dinero, lo típico de los veinte años. Y entonces a L. se le ocurrió aquella idea: una amiga de un amigo suyo conocía a alguien en Udine. Con suerte podríamos hacer algunas llamadas y quedarnos bajo aquel techo desconocido, a esperar que pasara la nevada.

Al final resultó que eran dos, muy parecidas, aunque no se trataban como hermanas. La semejanza la propiciaban las cabelleras rubias, inusualmente largas y brillosas, casi lo único limpio en aquellas muchachas de largas uñas grises y rostros amargados. A. trató de ser galante, elogió sus melenas, que caían hasta cintura, y una de ellas, entre sonrisas, nos explicó el secreto: pastillas anticonceptivas machacadas y disueltas en el champú. Nos lo enseñó una amiga cubana, por cierto. No había mucho de atractivo en sus cuerpos desgarbados, con perfiles rapaces, y menos en los abrigos mugrientos que las envolvían.

La primera noche, L. y yo nos ofrecimos para buscar algo de cenar, unas pizzas. Afuera seguía la nevada, y tuve que escuchar pacientemente todas las fantasías sexuales de L.: un tres pa’ dos, brother; eso está hecho, tú verás. Introduje mis reparos higiénicos y algunas sospechas en su visión pansexual; si no eran hermanas, o primas, aquellas muchachas eran una pareja, y nosotros ya debíamos estar agradecidos por no tener que pasar la noche en la estación. No valía la pena posar de donjuanes, era correr un riesgo innecesario.

Nos quedamos tres días, como si fuera la cosa más normal del mundo. Cada noche alimentábamos a aquellas rubias desaliñadas, que devoraban todo de inmediato, incluso lo de nuestros platos. Apenas tenían dinero para comer, nos contaron. Se alimentaban normalmente con lo que robaban del asilo donde trabajaban los fines de semana.

Hablar, lo que se dice hablar, no mucho. Nuestro chapurreado itañol tampoco ayudaba. Sentíamos confianza por compartir techo y comida, pero no nos atrevíamos a arriesgar más información. La maldición de la política entre exiliados, el presentimiento de que aquellas hippies trasnochadas simpatizaban con “aquello” que habíamos dejado atrás. Ahí estaba aquel póster gigantesco, bajo la mirada vigilante y algo estrábica del Guerrillero nos tocaba convivir y tratar de suplir la falta de calefacción con nuestros sacos de dormir. Una simple discusión, y quizá hubiéramos tenido que dormir en la calle. Las anfitrionas ya habían demostrado un carácter tempestuoso. Hablaban de amor, en inglés, con A.; le explicaban que alguna vez habían compartido un novio, pero luego se habían hartado de los hombres. Es como una postal, sabes —decía una. Cuando aún sigues amando pero ya no estás enamorada. Conservas un trozo del pasado que ya no podrás cambiar, una postal. Con cariño, “affection”. Con los hombres ya no puedo pasar de ahí. A. intentó explorar algún otro lazo. Pero la discusión se trasladó luego a la política y todos empezamos a agriarnos. No recuerdo los detalles de aquella noche, pero sí que terminó con un exceso de énfasis, caras largas y A. pegado a la botella de orujo que llevábamos en la mochila. Parecía como si cualquier asomo de virilidad fuese una afrenta en aquel gineceo mugroso, donde los recuerdos se enquistaban y el razonamiento quedaba reducido a la repetición de cuatro o cinco claves de manual izquierdista.

El último día nos acompañaron a la estación, aún nevada pero ya en servicio. Comentamos sobre Jason, el americano al que supuestamente conocía L., y cuya amiga habría pasado una temporada en casa de las rubias. Hasta ese momento los detalles eran vagos; tras varias llamadas, L. había dejado caer por teléfono varios nombres y se había ocupado de convencerlas de nuestra situación desesperada con particular elocuencia. Ahora, pasada la urgencia, trataban de empatar referencias. Pero Jason no ha estado en Cuba, le dijo de pronto una de ellas. ¿De qué Jason me hablas? Y entonces, en el andén, nos dimos cuenta del equívoco. Todo era un error, habíamos sido los huéspedes de unas desconocidas. Se creó un extraño malestar; era embarazoso descubrir que el amigo común en realidad no existía, que había sido una suerte de espejismo, una coincidencia. La corriente de simpatía que habíamos empezado a crear con aquella despedida se anuló de manera instantánea. Se sintieron traicionadas, creo. Nos despedimos aprisa, sin entrar en detalles, viajantes en busca de un dudoso espejismo.

Ernesto Hernández Busto (La Habana, Cuba, 1968). Poeta, ensayista, editor y traductor cubano residente en Barcelona. Entre sus títulos más recientes se encuentran La ruta natural (Vaso Roto, 2015) y Diario de Kioto (Cuadrivio, 2015). Colabora en El País.

Ernesto Hernández Busto (La Habana, Cuba, 1968). Poeta, ensayista, editor y traductor cubano residente en Barcelona. Entre sus títulos más recientes se encuentran La ruta natural (Vaso Roto, 2015) y Diario de Kioto (Cuadrivio, 2015). Colabora en El País.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.