A Conversation With Sergio Troncoso

Rose Mary Salum

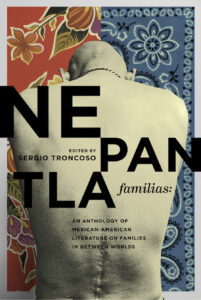

Nepantla Familias: An Anthology of Mexican American Literature on Families in between Worlds is an anthology edited by the award winning author Sergio Troncoso. The book brings together Mexican American narratives that explore the many permutations of living in between different worlds. Here is our conversation with the editor and author.

***

RMS: You’ve always broken Hispanic stereotypes in the English-speaking world. With this book, you return to a much-needed conversation: what does it mean to be Hispanic in the United States. What triggered the idea of a book of this nature?

ST: I was asked to be the editor of an anthology on Mexican Americans by The Wittliff Collections and Texas A&M University Press. They left the rest up to me. I wanted new work, not previously published work, and I also wanted writers to focus on Nepantla, living in between worlds, the middle ground that Mexican Americans inhabit between languages, cultures, geographies, and identities. I wanted to see how writers navigated the hybridity, the variety of resolutions and conflicts of Nepantla within their families. When you read Nepantla Familias, once and for all you will know that there is no such thing as a monoculture, or a static or stereotypical identity of Mexican Americans. What you will experience is the fluidity of identity.

RMS: What is the common ground of all the writers when choosing between the old world and its values and choosing the present with its new ways and values? What stands out to you from these works?

ST: I don’t think there is a common ground for the writers of Nepantla Familias when choosing between traditional values and so-called “new” values. But I think that’s the point: that for those living in the middle ground of Nepantla there is no common ground, no static form of identity, no easy or common choice to go this way or that. What stands out for me in all these works is how these writers are comfortable with uncertainty, how they embrace it, and how they find themselves in the fog of adopting the in-between. I think when you get too certain about who you are, you stop thinking, you stop looking, your curiosity starts to disappear. It’s difficult to live in uncertainty, but it’s also the most lived life.

RMS: In “Elote Man,” David Dominguez talks about how he is always confused as both Mexican and American. Would you say this is a triggering theme in Nepantla?

ST: “Elote Man” is an excellent essay about the push-pull of “being American but also being Mexican.” He’s proud of his ancestry, yet people in his community keep confusing him and judging him by stereotypes. By the way, this stereotyping comes from those who are Mexicans as well as those who are not Mexicans. I think the protagonist in this essay, David, wants to be both identities: he wants to be proudly Mexican, especially because of the relationship with his father, but David is also an American who is a professional, who owns a beautiful house, and has “made it” to the American upper middle class. So the confusion comes from the community, and how it sees him, as much as from within David: he wants to create a unique space in the in-between of Nepantla, where both identities belong together as something whole and unique.

RMS: Sandra Cisneros talks about home in her long poem, “I live al reves, upside down. Always have. Who called me here? The spirits maybe. A century later. To die at home for them” What is home for so many people living in Nepantla? What is home for you Sergio?

ST: I think home for me is wherever I am, wherever I have adapted to more or less find my place. This does not mean I completely fit in, or I don’t fit in. It’s simply the place where I decide to take a stand, where I decide to take care of my family, where I decide to navigate the many permutations of my fluid identity in Nepantla. I have often said that I’m like a turtle: my home is on my back, including the scars I have from my many travels, the adventures I adopted and those thrust upon me. I believe when I get too certain about my place, wherever that is, when I get too comfortable, I have stopped thinking, I have stopped asking tough questions about myself and what surrounds me, my community. I think that’s the truest sense of Nepantla as ‘home’: to be always expressing Empathy for others as well as seeking Empathy from them, to always be asking Questions, to be comfortable with Uncertainty, and amid all of that to have the strength of character to know who you are.

RMS: Many of the writers express the frustration of being either “too Mexican” or “not Mexican enough.” The rejection from both sides foments a desire to belong to something uniquely apart from either. That’s the reason Nepantla becomes such an important place in this book. Will that liminal place ever get integrated to the point of getting erased from our narrative?

ST: I don’t think so. I think Nepantla is already an integration, a new identity that is fluid, dynamic, nonconformist, and that exists against the monocultures of Mexico City as well as Washington, D.C. and anywhere else that demands a static definition of identity. So anyone who wants to determine themselves, instead of being determined by what you are supposed to be (based on stereotypes or national political narratives), will always embrace a version of Nepantla.

RMS: Let’s talk about the rejection that some writers feel. Is this rejection the responsibility of the society in general because of its racist forces and dynamics? Or is it the individual responsibility of each immigrant to overcome what is perceived as a rejection? I’m thinking of Alex Espinoza’s or Reyna Grande’s thoughts: I’m not enough, I’m insufficient.

ST: Well, I always think it starts with the overt and not so overt racism and xenophobia Mexican Americans often face in this country, from the fear of ‘foreigners,’ even though many of our ancestors have been here before Texas was Texas and before the United States was the United States; to the more subtle aspect of erasure that happens when Mexican Americans in the arts are practically invisible, often ignored in the New York publishing world as well as Hollywood movies, for example.

But the individual–as in the essays of both Alex Espinoza and Reyna Grande–struggles and sometimes succeeds to work against these obstacles. And sometimes we don’t succeed. Alex writes about how the toxic masculinity he faced within his family eventually morphed into a resilience to be better and to accept and be joyful about who he was. He told me recently, he now has a “Fuck it!” attitude about trying to be accepted as gay man who is also disabled: this is who he is, take it or leave it. Reyna writes about the trauma she faced in elementary school where she was punished for speaking and writing only in Spanish, how she learned English (which forced her to abandon her mother tongue), and how she reclaimed it by making sure her daughter was enrolled in a bilingual school. That’s another individual triumph, a triumph of affirming what was taken from you and making it better, but through a difficult gauntlet provided by society.

RMS: Octavio Quintanilla’s short poem conveys the fear of law enforcement that often haunts immigrants long after they arrive in America as well as the constant threat of deportation. The fear of law enforcement is well understood for African Americans but rarely for Hispanics. It is as if they (or their troubles) do not even exist in this society. Could you elaborate on this issue?

ST: Well, I think this is about the invisibility issue I’ve spoken about before. Latinos and Latinas are nineteen percent of the U.S. population, with Mexican Americans being about two thirds of this group. They certainly don’t have the political and news voice to be understood appropriately. They certainly do not get the political and news attention in comparison to other minority groups. And yet Latinos are a larger minority in the United States than African Americans or Asian Americans, for example.

I think this problem stems from many reasons. One reason is that because many Latinos speak Spanish, or are more comfortable in Spanish, so they are not accepted as “real Americans,” certainly by many white Americans, but even by other non-Hispanic minority groups. That’s simply true. Another reason is that the media seem to approach most minority issues as a Black vs. White problem, because that dichotomy is easier to understand, because of the Civil Rights Movement, because of the awful history of slavery. But that history of struggling for freedom often also ignores that Mexicans were slaughtered in Texas, before it was Texas, so that white Anglo settlers could claim Tejano lands for themselves. This American history mostly ignores that Texas broke away from Mexico, in part, to preserve slavery, because Mexico had made slavery illegal. Stephen F. Austin defended slavery for Texas. This long history of Mexicans on the border has been known, but too often ignored or not made part of the larger narrative of struggling for freedom in this country. Recent scholarship has helped to bring attention to what happened during Texas Independence and the role of the Texas Rangers in murdering and harassing Mexicans and Mexican Americans for years. This has helped this narrative join the larger narrative of struggling for freedom in the United States. But so much more needs to be done. Until the media picks up and expands upon these larger Latino narratives that include and appreciate the discrimination against Mexicans and other Latinos and the violence they suffered for generations, we will be stuck with a very limited and incomplete sense of the struggle for freedom in this country.

“real Americans,” certainly by many white Americans, but even by other non-Hispanic minority groups. That’s simply true. Another reason is that the media seem to approach most minority issues as a Black vs. White problem, because that dichotomy is easier to understand, because of the Civil Rights Movement, because of the awful history of slavery. But that history of struggling for freedom often also ignores that Mexicans were slaughtered in Texas, before it was Texas, so that white Anglo settlers could claim Tejano lands for themselves. This American history mostly ignores that Texas broke away from Mexico, in part, to preserve slavery, because Mexico had made slavery illegal. Stephen F. Austin defended slavery for Texas. This long history of Mexicans on the border has been known, but too often ignored or not made part of the larger narrative of struggling for freedom in this country. Recent scholarship has helped to bring attention to what happened during Texas Independence and the role of the Texas Rangers in murdering and harassing Mexicans and Mexican Americans for years. This has helped this narrative join the larger narrative of struggling for freedom in the United States. But so much more needs to be done. Until the media picks up and expands upon these larger Latino narratives that include and appreciate the discrimination against Mexicans and other Latinos and the violence they suffered for generations, we will be stuck with a very limited and incomplete sense of the struggle for freedom in this country.

Other reasons for Americans not appreciating the fears of Latinos for law enforcement: Latinos might feel powerless and don’t feel the police or the courts will respond to them. So Latinos might not file as many official complaints or pursue legal remedies. Some might fear they might be deported, and undocumented workers are always the most vulnerable to crime, because criminals know they will keep quiet and rarely report the bad things that happen to them.

RMS: The subject of language is also present in the book. Sheryl Luna’s poetry bring us news of how the masculine figure symbolized by her stepfather imposes the English language on her. Was the Spanish language ever rejected as a means of survival from economic struggles?

ST: Well, I would guess that sometimes the Spanish language was rejected because communities or schools around you did not appreciate that bilingualism would benefit immigrants or the children of immigrants. So in the short-term, someone might leave their Spanish behind to survive in a given situation, but over time you would see that losing your Spanish lessened you, that you could have and should have kept your Spanish if you could, if you had received more support in your school or community. I believe the more languages you speak, the more powerful you are. But speaking multiple languages in the United States is often not encouraged in this country. And using Spanglish, as is common on the border, is seen as something less, something bastardized (by both capitols, by the way), instead of seeing Spanglish as language creativity, important in itself for the Nepantla of the border, a linguistic form that deserves our respect and attention.

RMS: In the essay “Día de Muertos,” Stephanie Elizondo Griest speaks about the schizophrenic feeling of being biracial. Can you talk about the different races that are integrated in the term Hispanic and how this affects their survival skills in the U.S.?

ST: First, I’m not thrilled with the term Hispanic, nor even the terms Latinos or Latinx, because they make invisible Mexican Americans, by far the largest group within the broader terms. We also usually refer to ourselves as Mexican Americans or Chicanos, or we say we’re Dominican, Cuban, Puerto Ricans, Guatemalans, or even Central Americans. The broader terms come from political entities trying to see us as group without important distinctions, or even in stereotypes. Yet those distinctions always exist.

Latinos, as you know, come from all different races and all different religions. They are the “middle ground,” that mestizo upbringing and culture that has connected many different groups. I think if you are a Mexican American, and you are used to crossing borders (linguistic, geographic, religious, ethnic, racial) then my hope is that you would also have more Empathy toward others. That empathy would help you to survive in a place that is at once hostile and also welcoming. As the United States has more groups like Mexican Americans who have crossed many borders, my hope is that one day we will stop reacting against what we have lost in some minds, a White Protestant Nation, and embrace what we have become, a Mestizo Nation, with many groups interacting and meeting each other in the Nepantla middle. I hope over time our national identity will become more Nepantla fluid and dynamic, but we may have to endure many terrible conflicts to get there. And we should be ready to fight politically, whatever it takes, to make that happen. That’s the road to a true democracy, where everyone is encouraged to have a voice and to exercise it, and where los de abajo, wherever they are from, are active citizens.

RMS: One of the things that called my attention is that you include most genres of literature in this anthology. You have essays, poetry and short stories. What made you decide to include all these genres in this anthology? Did you encounter obstacles when trying to sell it to a publishing house?

ST: I saw that the literary creativity around the theme of Nepantla was in all of these genres. I wanted Nepantla Familias to reflect that creativity and to spur the reader to appreciate how expressing the many permutations and varieties of Nepantla could be explored in writing.

No, I did not encounter any obstacles trying to publish Nepantla Familias. The Wittliff Collections funded the project and encouraged me to edit a volume of Mexican American literature. Texas A&M University Press was their partner, and they’ve been wonderful to work with. At every point in the process, both The Wittliff Collections (Nepantla Familias is part of the Wittliff Literary Series) and Texas A&M University Press have supported me when I selected the theme and solicited the writers I wanted to solicit. They allowed me to have complete control over whom I accepted into the anthology and how I carefully arranged the pieces in the anthology. I also told them about Antonio Castro, a talented UTEP professor of graphic design, and that’s how he came to do the fabulous cover. So it’s been an exceptional publishing partnership that has resulted in a great anthology for all readers.

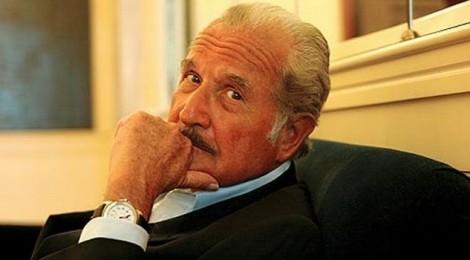

Sergio Troncoso (born 1961) is an American author of short stories, essays and novels. He often writes about the United States-Mexico border, immigration, philosophy in literature, families and fatherhood, and crossing cultural, religious, and psychological borders. He is the author of A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son, The Last Tortilla and Other Stories, Crossing Borders: Personal Essays, and the novels The Nature of Truth, From This Wicked Patch of Dust, and Nobody’s Pilgrims. He is the editor of Nepantla Familias and co-edited Our Lost Border. His Twitter is @SergioTroncoso

Sergio Troncoso (born 1961) is an American author of short stories, essays and novels. He often writes about the United States-Mexico border, immigration, philosophy in literature, families and fatherhood, and crossing cultural, religious, and psychological borders. He is the author of A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son, The Last Tortilla and Other Stories, Crossing Borders: Personal Essays, and the novels The Nature of Truth, From This Wicked Patch of Dust, and Nobody’s Pilgrims. He is the editor of Nepantla Familias and co-edited Our Lost Border. His Twitter is @SergioTroncoso

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: July 7, 2021 at 9:34 pm