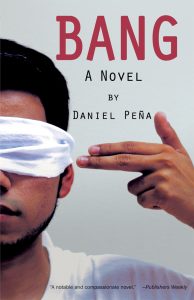

Bang

Greg Walklin

By Daniel Peña

Arte Público Press, 2018

Bang, the new novel by Daniel Peña, starts, fittingly, with a bang. In this case it is a literal bang, a plane crash, where two brothers, Cuauhtémoc and Uli, land on the wrong side—for them—of the border between Texas and Mexico. Cuauhtémoc and Uli, like their mother Araceli, are undocumented, and being stranded in Mexico means getting back to the United States is Herculean.

After the crash, the story divides in three, as Cuauhtémoc—the pilot in their late-night joyride—runs into a cartel hitman who is looking for “one more soul” in Matamoros, while Uli, significantly hurt, is alone and stranded in a hospital recovering from his wounds. Risking her own wellbeing, Araceli crosses back into Mexico in an attempt to track them down.

Cuauhtémoc, the older brother, leaves Uli and the wreckage to find help. Instead, after a violent confrontation, he is trapped in the criminal underworld of a small-time cartel. Because the cartel is in desperate need of someone to fly planes across the border, he is conscripted. A former crop duster, Cuauhtémoc has no choice but to sink—even as he he flies—into the criminal life:

“The contract is remarkably simple…If a brick goes missing, Cuauhtémoc dies. If Cuauhtémoc goes missing, they find Cuauhtémoc (wherever he’s at in the world) and Cuauhtémoc dies. They promise if they can’t find him, they’ll take next of kin…”

Uli escapes from his doctors, and eventually makes his way to his old house in San Miguel in Matamoros, hoping to see his father, who had been previously returned to Mexico. Fond of Coca-Cola, Uli is caught in a sort of limbo of identity, seeing the Mexicans around him as foreigners. The younger Uli is more at home in his Americanness: “And the sound of English—God, what he’d give to speak English to anyone about now, to read something in English, write anything in English to anybody who also speaks English.” When he meets June, whom the locals have dubbed “the sleeping girl,” and who had been squatting in his father’s house, he proves unable to form any kind of meaningful bond; the very sense of reality seems different between the two: “Like all Mexicans that Uli’s ever met—including his father (especially his father)—June acts like Hendrix is still alive, like Clapton never got old, like the Beatles never met Yoko.”

Meanwhile, Araceli’s struggle to find her sons seems doomed from the start. She has engine problems with the truck. She seriously injures her hand. She still has no idea where he husband disappeared to, whether he is even alive. Lucky to cross the border into the United States intact, going back seems suicidal, but she doesn’t care. Peña subverts the typical storytelling choice of showing the struggle of getting into the United States by showing the struggle Araceli has in returning to Mexico. It is a clever, and heart-wrenching, narrative turn.

A couple of plot holes mire the book, however—for instance, it defies belief that Cuauhtémoc and Uli would not try to get in touch with each other via Facebook or some other electronic means, given Araceli makes it a point to look at their profiles for activity. While Peña writes well, and with lush detail, the lengthy aeronautical descriptions ultimately do not seem to add much to the narrative. Both of these end up as distractions in what is an otherwise absorbing debut novel; Peña, a professor at the University of Houston-Downtown, renders the nightmarish Matamoros—with its packs of wild dogs, boulders in the street, burning vehicles, and macabre gambling on death in the *centro*—into a sort of DMZ that sears the imagination.

Overall, the book is slow-burning tale of perdition, where nothing seems like it will go right; it’s the kind that makes you bite your fingernails. And for American readers, it is certainly relevant right now: in times when immigration has risen, at least for a moment, higher into the United States’ national consciousness, Bang highlights the human toll border policy, and drug policy, exacts. (In a way, the story is similar to many headlines—a mother is separated from her children at the border, and does anything she can to get them back.)

The first line—“Misplaced is the word Araceli would use”—is a fitting encapsulation of how Cuauhtémoc, Uli and Araceli struggle against the world they live in, neither entirely welcome in Texas nor Mexico. Many things in Matamoros are reminders of why they left: tanks in the streets, murderous syndicates, cheating businesses, lawlessness—all of which make a decision to cross the Rio Grande, at least for them, a fait accompli. Even the stories at the periphery are haunting: the idle melancholy of the older prostitute Alma; the family tragedy of June, whose sister was mysteriously murdered, like so many other young women working in the maquiladoras; or the solitude of Lalo (the hitman) or Iván (a former photographer). Everyone is fighting against something much bigger than themselves, and their internal conflicts are, in some sense, a byproduct of the larger, inverted world the drug trade has created. “The dope has to go where it has to go,” a car mechanic tells Iván. “You can’t fight supply and demand.”

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

©Literal Publishing

Posted: July 26, 2018 at 9:30 pm

This isn´t my first time to visit this web page, but this is the first time I read such a good excerpt. I´m getting the book!