Cultures

Christopher Conway

In October 1841, Brantz Mayer, a thirty-two-year-old lawyer from Baltimore, Maryland, arrived in Mexico City to take his post as secretary to the US legation in Mexico. His hotel, the Gran Sociedad (Grand Society) was on the corner of Espíritu Santo and Refugio Streets, two blocks from the main plaza. Like other colonial structures on the block, the hotel was a two-story building with a spacious interior patio. Inside was a café that served snacks, ice cream, and liquor, and a fancy dining room that offered French meals twice a day. On the second floor there was a gaming room with billiards and card tables. The hotel was aptly named because it was frequented by the crème de la crème of Mexican society. On theater nights, couples dropped by the café for refreshments, and in the afternoons and evenings men of leisure filled the gaming room with their cigar smoke as they played cards.

After checking in, the eager traveler exited the Grand Society to take a walk and explore. As he wandered down the street, enveloped by the hubbub of city life, Mayer tipped his hat to the upper-class women, who wore expensive gowns and sported small, delicately embroidered pieces of fabric over their heads. He observed women of lesser means—clad in unadorned petticoats and plain dresses, and wearing colored shawls called rebozos—walking alongside barefoot Indians in misshapen, soft hats and torn clothes. Horse-drawn coaches rolled down the cobblestone street as groups of people crossed the thoroughfare.

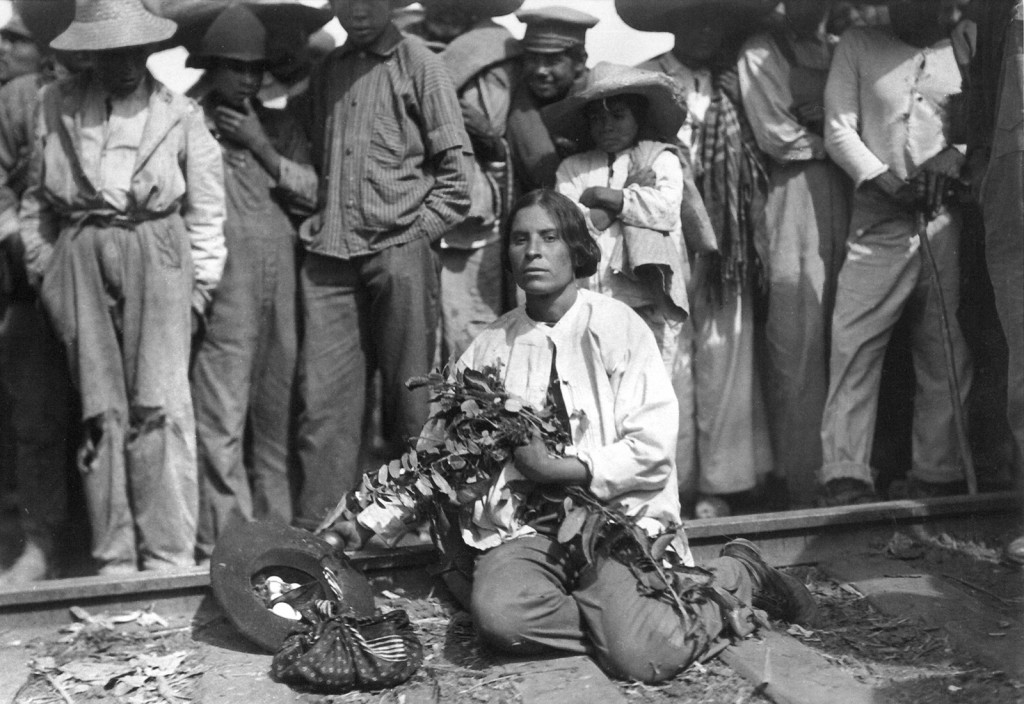

“Paseando por la ciudad” Imagen de Manuel Ramos en la Ciudad de México

Not far from the hotel, on Tacuba Street, Mayer sauntered along a row of street stalls that sold produce, drinks, and religious items. One shop in particular, a butcher’s stall, caught his eye: it was built out of four large boards, and had large cuts of beef hanging from the ceiling, garlands of linked sausage streaming across the boards, and a fierce-looking live rooster tied to the front counter. On the back wall of the structure was a cheaply printed image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, who had miraculously revealed herself to the Mexican peasant Juan Diego in 1531, and who had been the spiritual counsel and comfort of the Mexican people ever since. The dark, curly-haired butcher in his bloody leather apron was laughing as he spoke to the women in rebozos at his counter. He took out a small guitar and began to sing, making his customers laugh, but Mayer was too far away to understand the words. He pulled his pocket watch from his vest and realized he should get back to the Café de la Gran Sociedad for his appointment with other members of the US legation. He turned away from the butcher’s stall and walked back up the street, pausing once again to tip his hat to another lady of distinction, and trying to ignore the pleading children in rags at his heels.2

I describe scenes from Brantz Mayer’s arrival in Mexico City to use them as a metaphor for the subject matter of this work. Only a few blocks from his hotel, Mayer had encountered the rich and contrasting tapestry of mid-nineteenth-century Mexico, where different classes of people crossed paths and rubbed shoulders. He saw the accoutrements and spaces of privilege at the aptly named Grand Society and caught a fleeting glimpse of how the humbler classes lived and moved around the city. In light of these dramatic contrasts, limited to a few blocks of Mexico City in 1841, the idea of summarizing and interpreting nineteenth-century Mexican culture, to say nothing of Spanish American culture in general, seems impossible. After all, culture is everywhere around living people, in the organization of space, in variations of language, in pastimes and belief systems, and much more. Culture’s vast scope, variability, and changeable nature make it resistant to faithful re-creation, even if it had somehow been preserved in its entirety and undistorted in the historical record. And yet the contrast between the Grand Society and the butcher’s stall on Tacuba Street is a useful starting point for telling the story of nineteenth-century Spanish American culture. The coexistence of a culture of refinement and privilege with a culture of the street provides us with a framework for thinking about culture in a dynamic and complex way.

Image by Victor Casasola

This work explores the cultural forms that encapsulated the worldviews, lifestyles, and ideologies of Spanish American elites and commoners in the nineteenth century. By “cultural forms” I mean artifacts of human creation that are associated with both the fine arts and popular culture. The fine arts encompass literature, theater, music, dance, and painting, all of which have been associated with refinement and exclusivity in the modern Western world. Popular counterparts to these kinds of art forms—sensationalist novels and crime stories, neighborhood musicians, fandango dancers, and circus and other street entertainments—are generally accessible to more people because they are not tied to financial privilege or restricted to one class of people alone. The chapters that follow tell the story of both these kinds of culture: they tell the story of the literary tastes and reading habits of elites, the popularity of cockfights and street entertainments among commoners, and the ways that different classes of people viewed each other through cultural expression. This book examines trends and patterns in the production of cultural objects and explores the networks, institutions, and belief systems that framed and gave meaning to cultural creation.

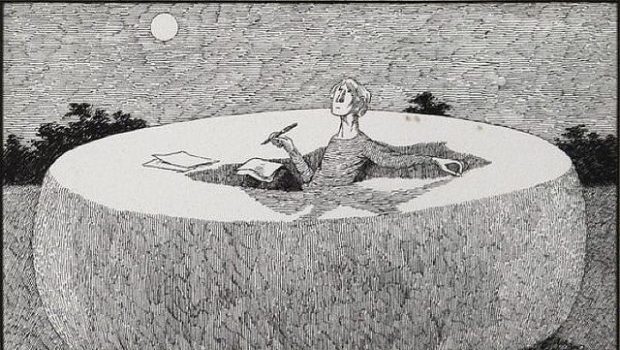

At its simplest, the argument here is that nineteenth-century Spanish American culture was forged through the opposition and intertwining of tradition and modernity. Republican statesmen, journalists, and writers used the idea of culture as an instrument to shape attitudes and promote social stability. Writing novels and plays, going to the theater, and enjoying classical music showed that a society was developing and improving itself. Cultural elites did not tire of promoting these activities, producing a vast body of print that celebrated culture’s regenerative powers, although they did little to include the majority of the people in their cultural communities. Indeed, elite pastimes were not an option for the majority of people because they were expensive and required forms of cultural literacy that were tied to financial privilege and high levels of education. The exclusivity of elite culture fostered prejudice among its practitioners, who frowned on the culture of commoners because they considered it indecorous, primitive, or contrary to their Europeanized ideology of progress. By the same token, the cultural expression and entertainments of commoners challenged the values and protocols of the elite and affirmed local identities and their distinctive voices and sensibility. This was not a uniform or organized resistance but rather an authentic expression of a different way of living and seeing the world. The popular theater, the circus, and puppet shows highlighted heroes who shared the language of the man and woman of the street, and whose spicy wit could and did criticize elites or bear witness to social injustice. If the culture of the educated was defined by restraint, and by a quest for order through new, Europeanized cultural forms, the culture of commoners was both freer and more steeped in the traditions of the past.

All the above may seem to cast the Grand Society and the butcher’s stall in opposition. While the divergences between the two are pronounced, cultural life was also very much about the convergence of the two; elite and popular culture were not located on unmovable, separate tracks, but rather on intertwined pathways. In 1852, for example, in a magazine article titled “Operas and Bulls,” the Mexican journalist Francisco Zarco complained of the popularity of bullfights among women of refinement, and expressed nostalgia for the days when elites frowned on this lowbrow entertainment. However, in a clever inversion of the usual opposition between the civilized culture of the elites and the “barbarian” entertainments of the masses, Zarco ended his article by attacking the indecorous and rude behavior of people who attended the opera. He complained of how they crammed dozens of family members into narrow theater stalls, chattering and laughing loudly. He griped that this suffocating mass of compressed and unruly humanity was an assault on other theatergoers, like an invasion of US soldiers or a pirate attack.3 For him, attending the opera was not in itself proof of refinement if patrons didn’t know how to behave properly during the performance or appreciate its moral superiority over bullfights. If a society’s entertainments crystallized its soul and essence, Zarco wrote, the fact that Mexican elites patronized both operas and bullfights underscored that they were lacking in character and refinement. Zarco’s humorous essay reminds us that we should not draw a simplistic and rigid opposition between so-called high and low culture. Elite and popular cultural forms exist in a shared continuum rather than in separate locations; cultural objects and expressions from opposite ends of the spectrum come together and move apart. They are rarely locked in place.

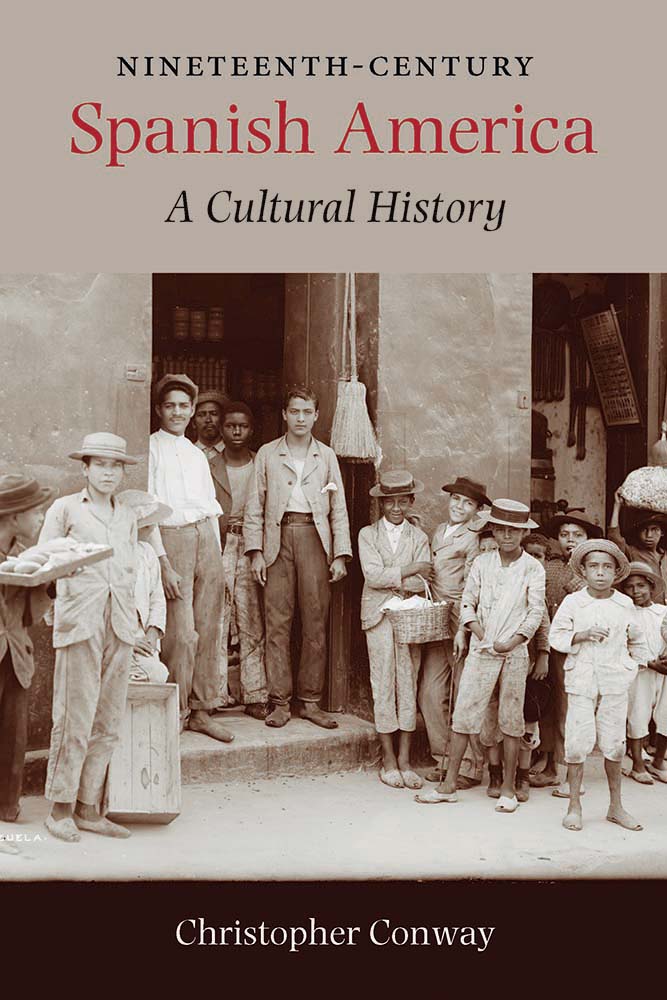

This text is an excerpt from the forthcoming book Spanish America, A Cultural History. Copyright: Vanderbilt University Press

Christopher Conway is Associate Professor of Spanish at the University of Texas at Arlington. He is author of The Cult of Bolivar in Latin American Literature (University Press of Florida, 2003) and editor of Peruvian Traditions (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Christopher Conway is Associate Professor of Spanish at the University of Texas at Arlington. He is author of The Cult of Bolivar in Latin American Literature (University Press of Florida, 2003) and editor of Peruvian Traditions (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Posted: August 4, 2015 at 11:43 pm