Six Portraits of Esperanza Velásquez Bringas (1896-1980) by Edward Weston

Fernando Castro

It has happened to so many important women. They leave their mark in society and afterwards, a biased historiography conceals them, diminishes them, or simply ignores them. But memory and historical documents usually endure long enough for someone to reflect and wonder: who was Esperanza Velásquez Bringas? Why did Edward Weston create six 8×10 portraits of her in 1924? This essay begins with Weston’s photographic study, which surfaced in Houston twenty years ago.

Except for one, five of the portraits frame the head and upper torso in a way that spells out a break with Pictorialism. Up until then, Pictorialist photographers were composing portraits as academic painters would: either full-bodied, or from the waist up. But circa 1920, Weston and Margrethe Mather (who was also his collaborator, model, and lover) started framing only the head. They focused on the mass of a person’s head as if it were an object: a nautilus shell, a book, or a bell pepper. For better or worse, to regard the face and head (the most significant parts of a person’s body) as objects is a thoroughly modern approach; fortunately, it is not the only modern approach. As in a passport photo or a Faiyum funeral portrait, there is little space left between the head and the edge of the picture. In Weston’s portraits the object-like treatment of the head is further underscored by the empty, neutral background that isolates the face from all distractors, circumstances, and accidental features. They offer no clue as to the vocation or profession of the person; in other words, they are extremely decontextualized. What gives this type of portrait its identity is the expression of the subject and his or her physical traits. Its particularity comes from the position of the head, its vantage point, its focus, and its lighting.

It is worth comparing these portraits with the Pictorialist 1902 portrait of Alfred Stieglitz by Gertrude Käsebier and with the traditional 1932 studio portrait of Frida Kahlo by her father, Guillermo Kahlo. The first one resembles a realistic charcoal drawing. Käsebier’s hand has intervened the print in order to achieve that effect. The second portrait summons the conventions of photographic studios that were at least eighty years old by 1930. At the start of the 20th century, some studios offered both kinds of photographic portraits. In Weston’s portraits of Esperanza the only remnant of Pictorialism is the soft focus, a technique he appeared to have given up around 1920. In fact, these portraits of Esperanza are very similar to the one Tina Modotti took of a young Dolores del Río in 1925.

Which of these six portraits did Weston pick? Or perhaps we should ask, which did Esperanza prefer? Weston printed and signed at least three of them. Were the portraits commissioned by Esperanza or offered by Weston? Why did Weston give the negatives to Esperanza?

In order to understand who Esperanza Velásquez Bringas was, it is worth retracing Edward Weston’s path from California to Mexico. It starts with Tina Modotti who, in 1921, became Weston’s favorite model and lover. Modotti had come to Los Angeles hoping to build an acting career in the movies. (2) At the time, she was married to the American artist/poet Robo (alias Roubaix de l’Abrie Richey, alias Ruby Richey). The couple came to know Weston in a circle of bohemian friends that included the Mexican poet Ricardo Gómez Robelo. That same year, Gómez Robelo was named head of the Fine Arts Department at Mexico’s Ministry of Education by none other than the controversial José Vasconcelos. Gómez Robelo invited Robo to move to México, offering him a job and a studio. Unaware that Tina and Weston were having an affair, Robo took some of Weston’s prints to Mexico in order to organize there a group exhibition of California artists.

Three months later, Robo died unexpectedly of smallpox. (3) Modotti was on her way to México when she heard the bad news. Although distraught, she decided to bring to fruition the exhibition at the National Academy of Fine Arts that Robo had planned. However, the very month of the opening, the news of her father’s demise forced Modotti to return to San Francisco. Back in California, she resumed her relationship with Weston and her photography apprenticeship to him began. They started living together and on July 1923, Weston left his wife Flora and three of his children and sailed off for Mexico with Modotti and his son Chandler.

Mexico had been in the throes of political and cultural upheaval since the start of the Revolution in 1910. Weston and Modotti arrived there in a particularly dangerous year. General Alvaro Obregón was in the midst of crushing the rebellion of his finance minister, Adolfo de la Huerta. (4) The United States supported Obregón with arms, ammunition and seventeen airplanes. By 1924, the year the six portraits were taken, Obregón was in full control, and under his aegis Plutarco Elías Calles was elected president of México. But Obregón had already bequeathed an important legacy. In 1920, he had appointed José Vasconcelos Secretary of Education. During Vasconcelos’s tenure, around 1,000 rural schools and 2,000 public libraries were built throughout Mexico. Vasconcelos, considered by many to be the father of Mexican indigenismo, wielded an influence that spread across the Americas. He promoted the muralist movement and through his initiative, artists like Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros were granted important commissions.

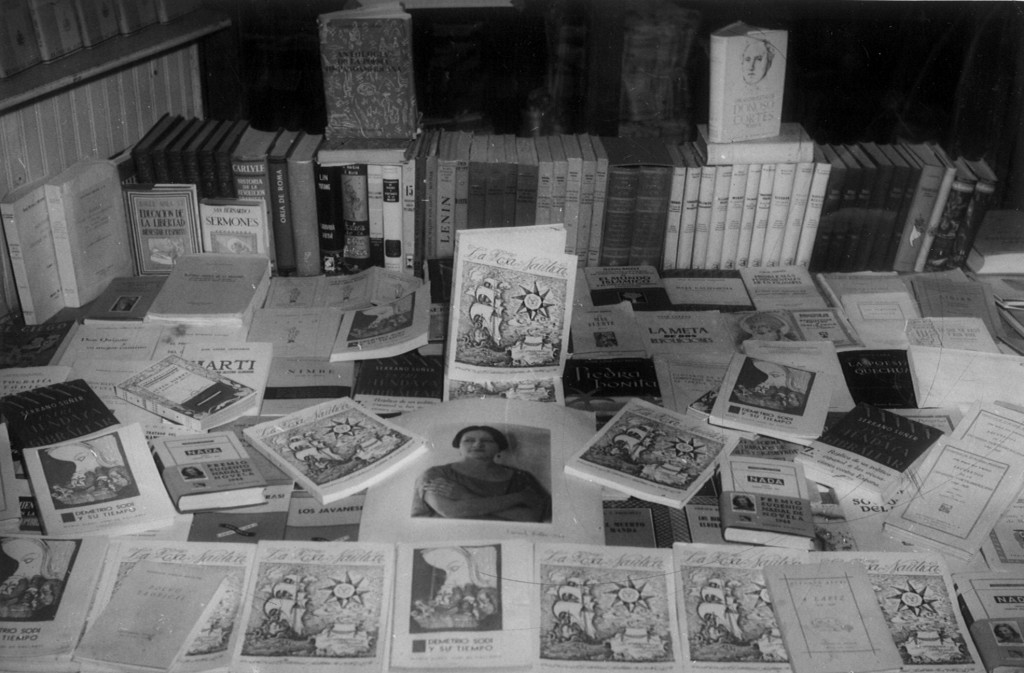

In 1924, however, Vasconcelos resigned in disagreement with Plutarco Elías Calles’s policies. That same year, Esperanza Velásquez Bringas became Director of Libraries. By then she had already forged a prestigious reputation as a journalist, educator, and advocate of women’s causes. By the age of eighteen, she had started writing for El Universal, a newspaper founded in 1916 to voice the principles of the Mexican Revolution. She was put in charge of the women and children’s section of the newspaper. Under anybody else’s command, that section could have been trivial and inconsequential, but Velásquez Bringas had strong and revolutionary beliefs about women’s rights, childrearing, motherhood, pre-natal care, birth-control, education, nutrition, eugenics, and civism. She can rightly be called “a first-wave feminist”; a Flora Tristan of the 20th century. Esperanza fought against the idea promoted by the porfiriato of the woman as “angel of the home” and promoted that of “the modern woman”. She herself was an unmarried working woman with no children, fashionably dressed, and very outspoken in political and intellectual circles. Her gift as an orator is evidenced by the fact that on the occasion of Charles Lindbergh’s visit to Mexico in 1927, President Elías Calles asked her to give a welcoming speech. Her ideas filled a void in the ideology of the Revolution and her charismatic personality endeared her to its leaders. She often wrote and voiced the profile of the Mexican regime for internal and external consumption.

But how did Weston’s path cross hers? Was it simply from being part of the same bohemian and revolutionary milieu? Weston had two very successful exhibitions at Aztec Land thanks to which his prestige as an artist and his portraiture clientele grew rapidly. Did Esperanza commission the portraits after one of these exhibitions? Other notable artists like Roberto Montenegro and Jean Charlot also took portraits of her. Finally, both Weston and Esperanza published their work in the El Universal, where she had been writing for years. Was a friendship established through this newspaper? Or was that friendship achieved through their mutual friend, Diego Rivera? There is a photograph in which she is standing next to Diego Rivera and a man holding a large format camera on his shoulders who looks like Weston. Did Esperanza bestow favors on Weston through her governmental or journalistic connections? Edward Weston destroyed his early journals, so there is no evidence regarding the exact nature of the relationship between Esperanza and him. Weston returned to California in 1927.

As for Esperanza, modern woman that she was, she continued living freely, productively, and dangerously. Her popularity increased when she became the host of a radio show called The National Hour. She belonged to several political and journalistic organizations: the Socialist Party, the Mexican Labor Party, the Confederation of Labor and Popular Organizations, the Association of Revolutionary Journalists and Artists, and the Press Editors’ Union. Together with presidents Plutarco Elías Calles and Emilio Portes Gil, she helped organize the Revolutionary National Party (which later became the Institutional Revolutionary Party or PRI). As a journalist, she pioneered the interview, a genre that years later would be made famous by the likes of Oriana Fallaci and Barbara Walters (both born in 1929).

As a lawyer, Esperanza was a public defender in criminal trials. After thirty years of service, she received a Gold Medal of Excellence from the Supreme Court of Justice. Her bibliography describes the gamut of interests over the course of her lifetime: politics, law, literature, women’s issues, education, and the world at large.

During one of her many trips around the country a cristero recognized her and pointed a gun at her. (5) Realizing the man meant to kill her, she tried to dissuade him by giving him her jewels. The man took them but tossed her out of the train and shot at her point blank. She managed to avoid being killed by rolling over. Only one bullet hit her right shoe, which she kept as a memento. (6) In Lecturas populares, one of the most widely read books compiled by her, she wrote to her grandmother: “I find it difficult to believe today, and so I thank you for having filled my childhood imagination with the thaumaturgy of fantastical tales.” (7)

*Images courtesy of Maria Luisa de Gortari

NOTES:

(1) In the late nineties, the Center for Creative Photography in Arizona, which holds one of the most important Edward Weston archives, acquired from María Luisa de Gortari, a Houston resident, six 8×10-inch Weston negatives. Mrs. De Gortari had inherited these portraits of her godmother Esperanza Velásquez Bringas when the latter died in 1980. Given the vast estate of EVB, Mrs. Gortari did not realize until years later that she had also inherited vintage prints signed by Edward Weston of those very same portraits.

(2) Tina Modotti starred in the movie The Tiger’s Coat (1920).

(3) Some sources state that Robo died of tuberculosis which is unlikely, given that his death was so sudden.

(4) “December brought not only the inauguration of Plutarco Elías Calles as the country’s new president, but the roar of cannons and the threat of revolution. Dissident congressmen and military officers backed Adolfo de la Huerta, a former general and once interim president, in a rebellion that lasted from early December to March. Progressives rallied to support the government troops against the rebels, amid reports from the countryside that de la Huerta’s supporters were executing Communists and peasant leaders.” (Hooks, page 78).

(5) The Cristero War was a violent rebellion against the anti-clerical and anti-Catholic policies of the Plutarco Elías Calles regime. It started in 1926, and its effects were felt until 1940. Among other things, the cristeros were against the secular education of children in public schools. It is believed that some 300 public school teachers were murdered by cristeros.

(6) Personal interview with Maria Luisa de Gortari, Esperanza’s god-daughter.

(7) We fail to understand how the Center for Creative Photography acquired the copyrights for these images when it acquired the negatives from Ms. de Gortari. Given the exorbitant price the CCP now asks for publishing these images, the portraits could not accompany with this essay.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Constantine, Mildred. Tina Modotti: A Fragile Life. New York: Rizzoli, 1983.

Hooks, Margaret. Tina Modotti: Photographer and Revolutionary. London: Pandora, 1993.

Poniatowska, Elena. Tinísima. Mexico: Biblioteca Era, 1992.

Velásquez Bringas, Esperanza. La influencia psíquica materna sobre el niño durante la gestación. Mexico: 1921.

Velásquez Bringas, Esperanza. Pensadores y artistas. Mexico: Editorial Cultura, 1922.

Velásquez Bringas, Esperanza. En Soledad de la Mota. Mexico: Partido Laborista Mexicano, 1921.

Velásquez Bringas, Esperanza. El arte en la Rusia actual. Mexico, 1923.

Velásquez Bringas, Esperanza. El contrato de trabajo en el derecho mexicano. Mérida: 1924.

Velásquez Bringas, Esperanza. México ante el mundo. Barcelona: Editorial Cervantes, 1927.

Velásquez Bringas, Esperanza. Lecturas populares. Mexico: (3rd Edition) Editorial Turanzas del Valle, 1935.

Velásquez Bringas, Esperanza. Indice de escritores. Mexico: Talleres Gráficos de Herrero Hermanos Sucs., 1928.

Velásquez Bringas, Esperanza. La Rosa Náutica. Mexico: Editorial Cultura, 1947.

Velásquez Bringas, Esperanza. Japón. Mexico: Editorial Orión, 1968.

Weston, Cole and Morgan, Susan. Edward Weston: Portraits. New York: Aperture, 1995.

Fernando Castro is an artist, critic and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University as a Fulbright scholar. He is a member of the art board of FotoFest and of the advisory board of the Houston Center for Photoography. He is a contributing editor of Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal, and Spot. Last year he delivered the lecture “Elian” at the University of Cambridge, England.

Fernando Castro is an artist, critic and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University as a Fulbright scholar. He is a member of the art board of FotoFest and of the advisory board of the Houston Center for Photoography. He is a contributing editor of Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal, and Spot. Last year he delivered the lecture “Elian” at the University of Cambridge, England.

Posted: February 28, 2016 at 10:10 pm

loved this article!