From History to Geography, Conversation with James Hillman

De la historia a la geografía, Conversación con James Hillman

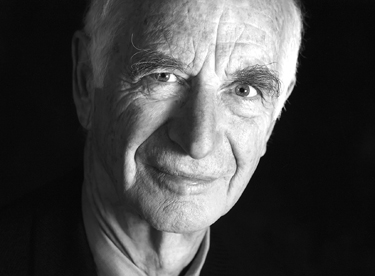

James Hillman

James Hillman is an American Psychologist, leading scholar in Jungian and post-Jungian thought, considered by many to be one of the most radical and original critics of contemporary culture. His innovative approach-archetypal psychology-emphasizes the importance of imagination in bothy psychology and in daily life.

His work and writings comprise several fields, such as psychology, philosophy, mythology, arb, and cultural studies. One of his most important works is the groundbreaking and Pulitzer Prize nominated book Re-visioning Psychology; Re-visioning Psychology; other important books include The Myth of Analysis, The Dream and the Underworld, and The Thought of the Heart.

Throughout his work, Hillman has criticized the literal, materialistic, and reductive perspectives that often dominate the psychological and cultural arenas. His attempt is to give psyche its rightful place in psychology and culture, fundamentally through imagination, metaphor, art, and myth.

* * *

Gustavo Beck: You are known for being one of the toughest critics within the field of psychology. You are particularly incisive when speaking about psychotherapy; so probably a good way to begin is by asking you if you consider psychotherapy to be a relevant discipline in today’s world.

James Hillman: In practice, it is very relevant. The practice of psychotherapy can be extremely important when dealing with people who suffer from serious disorders. There is plenty statistical evidence to demonstrate that in many cases of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression, medication is not sufficient; the importance of long term psychotherapeutic treatment in these cases is undeniable.

GB: This is when we talk about individual cases, but what about the role of psychotherapy as a cultural phenomenon?

JH: When we speak about culture, the importance of psychotherapy is a strange one. The greatest diffi culty that we find when talking about this is the fact that psychotherapy invisibly supports a whole infrastructure. Psychotherapists work with all the mess of society: abuse, deficiencies in education, family violence, addiction, and so on and so forth. No one can deny that it indeed helps the person function within society and the system. But this is precisely the problem for psychotherapy: that it is still within the system. It is immerse in the same system that causes the problems that it treats.

GB: So should psychotherapy move out from this system? Is that even possible?

JH: What we have to keep in mind is that the problem does not lie in psychotherapy itself, but in the theories that support it.

GB: What do you mean by this?

JH: Usually, when a psychotherapist thinks of a problem, he thinks of it as being something internal, as if the conflict resided inside the patient. This is highly problematic, because when whatever is affecting the patient is seen as internal, there is a failure to notice the external factors, by which I mean the political or cultural aspect of a conflict, for example. One of therapy’s worst problems is that it operates within the Cartesian model of subject and object—it is this attachment that is harmful for psychotherapy, and that is why it has to be moved somewhere else.

GB: Moved where?

JH: It has to be moved beyond the individual and into the world—this is what I am referring to when I speak of Anima Mundi in my writings. Other authors, such as Mary Watkins, have done plenty of work on the matter, taking psychotherapy beyond the consulting room and situating it in the world, in community, and in nature.

GB: How is this done?

JH: Well a first step was given by System Psychology. This model situates sickness in a new place; instead of confining I to the individual, it sees the conflict in the light of the system that embeds it. This is very useful because it allows for work with family and social issues. But this is not enough, we have to go even further than family and society.

GB: Where, for example?

JH: Take architecture, for instance; we seldom wonder about how the space we move in affects our psychology: the speedways, the office cubicles, the classrooms… Place is extremely important, it has a very deep impact on the psyche, and it is often neglected.

GB: So, if we have to go beyond individual, family, and society, what do you think is being neglected the most in psychotherapy?

JH: I would say that would be the aesthetic sense of life. Psychotherapy seems to be very anaesthetized.

GB: And what can we expect in the future for a psychotherapy such as this?

JH: I never speak about the future; doing so belongs to the American fantasy, and I do not to subscribe to that.

GB: Fair enough, let us return to the present then. Given this anaesthetized panorama, why would anyone be interested in becoming a psychotherapist?

JH: I do believe that there are certain individuals who have a calling to feel for the pain and misery of other people. Some of them are capable of following their calling—those individuals should become psychotherapists. Again: the problem does not lie in psychotherapy; it is the actual theory that is destructive. This is the dilemma of the psychotherapist.

GB: What is the dilemma?

JH: Well the dilemma of the psychotherapist is quite simple: how to remain helpful within the psychotherapy model while remaining true to his or her feeling for the patient.

GB: Very well. We have established that there are many problems in the theoretical foundation of psychotherapy, which has to go beyond the consulting room and the Cartesian notion of subject an object in order to come into community and nature; and that this could probably help restore the aesthetic sense that it lacks nowadays. Is this accurate?

JH: It is.

GB: Good. Let us go from psychotherapy in general to its situation in a particular context. Let us turn South. What do you think is the state of Latin American psychotherapy?

JH: I do not know much, really. I know that there is a very strong psychoanalytical community in Argentina, and I am also aware of a very active and diverse Jungian movement in Brazil, particularly in Rio de Janeiro and São Paolo.

What I think is very important is for psychotherapy to find its roots in its culture and its geography—it has to be true to the spirit of the land on which it exists. This can be applied to any psychotherapy in any place of the world, but it is particularly important for Latin America. It is crucial that you do not import other styles or ideas; and you should especially avoid buying into the Dream of the North—El Sueño del Norte. Latin America has a very rich imagery, embedded in its culture, its art, and its history—it is from there that Latin American Psychology should emerge.

GB: So you think there is a danger in adopting the same psychology that is applied in the United States, for example?

JH: The thing is that any psychology should be connected with the basic images that are woven in the fabric of its culture. Different cultures have different myths, different literature, different stories, and different visions of the world. The task of Latin American psychotherapists is to develop a kind of therapy that is connected and fundamented in their own culture. This has been done already by some people—the work of Paul Freire in Brazil is an example of it.

GB: Do you think there should be a dialogue between Latin American psychology and American or European Psychology?

JH: Probably, but before any possibility of dialogue, there has to be a Latin American version of psychotherapy.

GB: When you say “Latin American version of psychotherapy,” do you mean that Latin America has to generate its own style of psychotherapy?

JH: Exactly, you have to build a Latin American way of doing therapy—one that has its own methods. It is true that there is a lot of diversity within Latin America, and that the mythologies and stories vary from country to country. However, there are several common factors shared by most. The colonizing period, for example, was experienced by almost the whole region—be it under the Spaniards or under the Portuguese. One common trait of Latin America is that it has been constantly under economic, political, and social oppression; first by the conquistadores, then by the Catholic Church, now by American Corporations. This is precisely why it is important for Latin American psychotherapists to develop their own methods, and not adopt other styles, that would bring you back to the colonizing myth.

One of the greatest problems in Latin America is this obsession with its historical oppression. This history is important, but the obsessive attachment to it can become an obstacle. This is like the problem of keeping psychotherapy within the consulting room, and trapped in the Cartesian vision—this kind of obsessions are very dangerous. If a new version of psychology is to be born, there has to be a shift that leads away from this obsession. Instead of history, you have to turn your focus into geography.

GB: What do you mean turning our eyes into geography?

JH: I mean turning the attention into land and landscape: into mountains, rivers, forests, deserts, jungles. Again: place and aesthetic sense. Geography is much deeper than History—it is there where you can find the richest archetypal images. You should look for the animal soul that is rooted in nature. This is a good way of finding a style of psychology that fits the culture.

GB: But how is it possible to simply look away from hundreds of years of history?

JH: Of course you should not look away from history. I am not suggesting to look away from it, but to look below it. Look into geography and into the land, it is there where you can find the images that will lead you to an original version of psychotherapy that will be congruent with Latin American Culture.

James Hillman —psicólogo y académico estadounidense— es uno de los principales representantes del pensamiento post-junguiano. Considerado por muchos como uno de los más radicales y originales críticos de la cultura contemporánea, es uno de los fundadores del movimiento conocido como Psicología Arquetipal, el cual enfatiza la importancia de la imaginación en la psicología y la vida cotidiana.

Su obra trasciende el campo de la psicología y se extiende a través de otras disciplinas, como la filosofía, la mitología, el arte y las ciencias sociales. Entre sus obras más importantes se encuentra Re-imaginar la psicología, libro revolucionario que fue nominado al Premio Pulitzer. Ha escrito también El mito del análisis, El sueño y el inframundo y El pensamiento del corazón, entre otros.

A lo largo de su obra, Hillman critica las perspectivas materialistas, reduccionistas y literales que frecuentemente dominan el panorama psicológico y cultural. Sus escritos, a través de la imaginación, la metáfora, el arte y la mitología, buscan situar a la psique en el lugar que por derecho le pertenece en la psicología y la cultura contemporáneas.

* * *

Gustavo Beck: Usted es conocido como uno de los críticos más duros en el campo de la psicología, y sus ataques son particularmente incisivos cuando habla sobre psicoterapia. Probablemente sería conveniente comenzar esta entrevista preguntando cuán relevante considera a la psicoterapia en el mundo actual.

James Hillman: Como práctica, es muy relevante. La práctica de la psicoterapia es particularmente importante cuando estamos tratando con personas que sufren trastornos severos. Hay una gran cantidad de evidencia estadística que demuestra la insuficiencia del tratamiento farmacológico en casos de esquizofrenia, trastorno bipolar y depresión. En estos casos, la importancia de la psicoterapia a largo plazo es innegable.

GB: Esto hace referencia a la aplicación en casos individuales. ¿Pero cuál es el papel de la psicoterapia como fenómeno cultural?

JH: La importancia de la psicoterapia a nivel cultural es extraña. La mayor dificultad que encontramos al hablar de este tema es el hecho de que la psicoterapia sostiene secretamente a toda una infraestructura. Los psicoterapeutas trabajan con la suciedad de la sociedad, como el abuso, las deficiencias educativas, la violencia intrafamiliar, las adicciones, etc. Nadie puede negar que la psicoterapia contribuya a que la persona funcione mejor dentro de la sociedad y el sistema. Pero ese es precisamente el problema de la psicoterapia: que se encuentra dentro del sistema. Está inmersa en el mismo aparato que causa los problemas para los que provee tratamiento.

GB: ¿Habría entonces que mover la psicoterapia y colocarla fuera del sistema? ¿Es eso siquiera posible?

JH: Lo que hay que tener en mente es que el problema no reside en la psicoterapia como tal, sino en las teorías que la sostienen.

GB: ¿A qué se refiere con esto?

JH: Usualmente, cuando un psicoterapeuta contempla un problema, lo piensa como algo interno —como si el conflicto residiera dentro del paciente. Esto es sumamente problemático; si la afección del paciente se mira como algo interno, se tiende entonces a ignorar ciertos factores externos, como por ejemplo las facetas políticas y culturales de un conflicto. Uno de los mayores males de la psicoterapia es que opera dentro de la visión cartesiana de sujeto y objeto. Este modelo es dañino para la psicoterapia, es por ello que hay que moverla a algún otro lugar.

GB: ¿Moverla a dónde?

JH: Hay que llevarla más allá del individuo y llevarla al mundo —a esto me refiero cuando hablo de Anima Mundi en mis escritos. Otros autores, como Mary Watkins, han hecho mucho trabajo en esta materia, todos ellos buscan sacar la psicología del consultorio y colocarla en el mundo, la comunidad y la naturaleza.

GB: ¿Cómo puede lograrse esto?

JH: El primer paso ya fue dado por la psicología sistémica; su modelo coloca a la enfermedad en un lugar distinto; en lugar de confinarla al individuo, la ven a la luz del sistema que la sostiene. Este movimiento es muy útil, puesto que permite trabajar con la familia y las problemáticas sociales. Sin embargo, esto no es suficiente, tenemos que ir más allá de la familia y la sociedad.

GB: ¿Hacia dónde?

JH: Pensemos, por ejemplo, en la arquitectura. Pocas veces reflexionamos sobre la manera en la que el espacio en que nos movemos afecta nuestra psicología: las carreteras, los cubículos de oficina, los salones de clase… La noción de lugar es extremadamente importante, su impacto sobre la psique es sumamente profundo, y usualmente ignorado.

GB: Entonces, si hay que ir más allá del individuo, de la familia y la sociedad, ¿qué cree usted que es lo que la psicoterapia está pasando por alto?

JH: Yo diría que la psicoterapia ha olvidado, fundamentalmente, el sentido estético de la vida. La psicoterapia parece estar muy anestesiada.

GB: ¿Y qué se puede esperar para el futuro con una psicoterapia como ésta?

JH: Jamás hablo sobre el futuro; eso pertenece a la fantasía norteamericana, a la cual yo prefiero no adherirme.

GB: De acuerdo. Regresemos al presente entonces. Dado este panorama anestesiado, ¿por qué querría alguien convertirse en psicoterapeuta?

JH: Siempre hay ciertos individuos que son más sensibles al dolor y el sufrimiento humano, y algunos de ellos son capaces de seguir su llamado a trabajar con ello. Esos individuos deben convertirse en psicoterapeutas. Recordemos de nuevo que el problema no se encuentra en la psicoterapia; es la teoría la que es destructiva. Ese es el dilema de cualquier psicoterapeuta.

GB: ¿En qué consiste el dilema?

JH: El dilema del terapeuta es muy simple: cómo seguir siendo de ayuda dentro de las limitaciones del sistema psicoterapéutico sin dejar de ser fiel a su sensibilidad sobre el paciente.

GB: Bien. Hemos establecido entonces que hay problemas en los cimientos teóricos de la psicoterapia, que ésta debe trascender el consultorio y la noción cartesiana de sujeto y objeto, para así poder salir a la comunidad y la naturaleza; y que esto probablemente ayudaría a restaurar el sentido estético que actualmente carece. ¿Cierto?

JH: Cierto.

GB: De acuerdo, pasemos entonces de las generalidades de la psicoterapia a su situación en un contexto particular. Miremos hacia el sur. ¿Cuál cree usted que es la situación de la psicoterapia en Latinoamérica?

JH: La verdad es que no sé demasiado. Sé que hay grupos psicoanalíticos muy importantes en Argentina, y estoy enterado también sobre la existencia de un movimiento junguiano muy activo en Brasil, particularmente en Río de Janeiro y São Paolo.

En mi opinión, lo más importante es que la psicoterapia encuentre sus raíces en su cultura y su geografía —debe ser fiel al espíritu de la tierra que la hospeda. Esto puede aplicarse para cualquier psicoterapia en cualquier parte del mundo, pero es particularmente importante para América Latina. Es crucial que eviten importar estilos e ideas ajenas, y deben especialmente evadir comprar el “sueño del norte”. Latinoamérica posee una imaginería inmensa y rica que se desprende de su cultura, su arte y su historia —la psicología latinoamericana debe emerger de las imágenes provistas por esa riqueza.

GB: ¿Considera entonces que hay un peligro de adoptar la misma psicología que se practica, por ejemplo, en Estados Unidos?

JH: Lo que sucede es que cualquier psicología tiene que estar conectada con las imágenes fundamentales que conforman su tejido cultural. Diferentes culturas poseen diferentes mitologías, diferentes literaturas, diferentes historias y diferentes visiones del mundo. La tarea de los psicoterapeutas latinoamericanos es desarrollar un tipo de terapia que sea congruente y esté fundamentada en su propia cultura. Algunas personas ya han hecho labor en este respecto —el trabajo de Paul Freire en Brasil es un buen ejemplo.

GB: ¿Cree que debería existir un diálogo entre la psicología latinoamericana y la psicología estadounidense o europea?

JH: Probablemente, pero antes de cualquier diálogo, debe haber una versión latinoamericana de psicoterapia.

GB: Cuando habla de una “versión latinoamericana de psicoterapia”, ¿quiere decir que Latinoamérica debe generar un estilo determinado de hacer terapia?

JH: Exactamente, hay que construir un modo latinoamericano de hacer terapia —uno que posea sus propios métodos. Aunque es verdad que dentro de América Latina hay gran diversidad, y que cada país tiene su propia mitología y sus propias historias, también lo es que hay factores comunes casi a toda la región. Los tiempos de la colonización, por ejemplo, fueron experimentados por la mayoría; ya sea en manos de los españoles o de los portugueses. Una de las características principales de América Latina es que ha estado bajo una constante opresión económica, política y social; primero por los conquistadores europeos, luego por la iglesia católica, y ahora por las corporaciones norteamericanas. Por esto es tan importante que los latinoamericanos desarrollen sus propios métodos y eviten adoptar estilos ajenos que sólo los regresarían al mito de la Colonia.

Uno de los grandes problemas de América Latina es la obsesión con esta opresión histórica. Esta historia es importante, pero el apego obsesivo puede convertirse en un obstáculo. Es igual que lo que mencionaba sobre la problemática de mantener la psicoterapia dentro del consultorio y encerrada en la visión cartesiana —ese tipo de obsesiones son muy peligrosas. Si una nueva versión de psicología ha de nacer, debe haber un viraje que apunte lejos de esta obsesión —hay que dejar de concentrarse en la historia y mirar hacia la geografía.

GB: ¿A qué se refiere con mirar hacia la geografía?

JH: Quiero decir que hay que poner la atención en la tierra y el paisaje: en los ríos, las montañas, los bosques, los desiertos, las selvas. De nuevo: la noción de lugar y el sentido estético. La geografía es mucho más profunda que la historia, es ahí en donde encontrarán las imágenes arquetípicas de mayor riqueza. Deben buscar el alma animal que está enraizada en la naturaleza. Este es un buen método para encontrar un estilo de psicoterapia que vaya de acuerdo con la cultura del lugar.

GB: ¿Pero cómo es posible apartar la vista de cientos de años de historia?

JH: Por supuesto que no hay que apartar la vista de la historia, lo que yo sugiero es que se debe mirar debajo de ella. Hay que dirigir la vista hacia su geografía, hacia su tierra, es ahí donde encontrarán las imágenes que los llevarán a una versión original de psicoterapia, una que sea congruente con la cultura latinoamericana.

Thanks 🙏