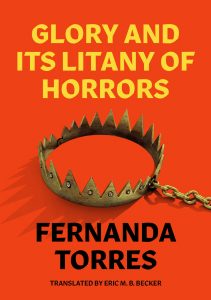

Glory and its Litany of Horrors (Excerpt)

Fernanda Torres

Excerpt from Glory and its Litany of Horrors

Translated from the Portuguese by Eric M. B. Becker

Brazilian actor Mario Cardoso recounts a disastrous performance of King Lear, which would go on to set his downfall into motion.

One moment was all it took—Blow, winds, I howled amid the storm, despite the hoarseness that had dogged me since opening night; the cast shook their metal thunder sheets, the inane idea of the genius director with ambitions of outshining even Shakespeare. The tense rehearsals, the disaster that is Portuguese, employing three times as many words as English to say the exact same thing, my head spinning from one scene to another, and another, and another, BAM. Any illusion that things were somehow improving went down the drain the day the re-inventor of the wheel handed strips of sheet metal to all the actors and ordered the idiots to shake the damn things with the fury of wild beasts. A laughingstock, thanks to the fact that yours truly, in addition to playing the lead role, was the one paying all those people to be there: the one behind the production who’d had the brilliant idea to go after corporate charitable contributions to achieve his dream of being something more than a mediocre actor of the tropics.

Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! rage! blow!

You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout

Till you have drench’d our steeples, drown’d the cocks!

In the two months leading up to the premiere, the voice coach, a cross between a shaman and a doctor honoris causa, had me repeat the storm soliloquy on all fours atop her rug in some decrepit office tower in Copacabana. I did as she instructed, there on all fours, on the rug, trusting her theory that this was the only way I would reach the depths of the King’s humiliation. Brazil lacks any sort of royal sentiment: we’re a bunch of plebes, we jeer our King Joãos and our Prince Pedros, the republic we founded was a half-assed job. Laurence Olivier would never have been made to get down on all fours, but there I was, on all fours, in a cubicle in Copacabana. I knew all about humiliation; what I lacked was the dignity to wear a crown, none of us have it. I was certain of that each time I left the cramped room in the office tower on Rua Figueiredo Magalhães, somewhere between depressed and exhausted, on my way to yet another grueling day of rehearsals. At the time, I still clung to hope. The illusion of glory. Everything began to fall apart the day the asshole director handed the cast their metal thunderbolts and told the beasts to wag the damn things. Stein, I said (the visionary’s name was Stein), no one’s going to hear a word with all that going on. He sneered and told me it wasn’t the words that mattered, only the deconstruction of the text and some nonsense about the theater of images. Go direct a puppet show, I thought, you could send for those giant dolls they march through the streets at Carnaval. I was about to explode, but fear of losing the director a month before the premiere convinced me to hold my horses.

Center stage, I repeated the verses with my paws on the ground, a king without a kingdom, Lear incarnate. In my distress, my mind turned to exorcism, black magic, I considered suicide and even murder. Stein’s, of course. These homicidal thoughts are what kept me going right up through the final dress. The satisfaction of all that rage. In the place of Goneril and Regan, the callous daughters of the monarch without a throne, all I saw was Stein; I unleashed my hate upon him and I felt better, even too much better. That ingrate hadn’t directed a production in more than ten years. I’d rescued him from his farm in Corrêas, the hideaway where the great promise of eighties theater had taken refuge after declaring humanity incapable of understanding his sublime creativity.

And thou, all-shaking thunder,

Smite flat the thick rotundity o’ the world!

Crack nature’s moulds, all germains spill at once,

That make ingrateful man!

This loathing for the director was only one of my problems. The scenographer and the costume designer, two old married queens who only worked together, made the nightmare complete. The first dreamt up a medieval castle wall that took a forest’s  worth of the finest wood. The giant logs were so heavy that I was forced to hire an engineer to reinforce the beams beneath the stage. Stage—it was a theater in the middle of a shopping center, a transvestite England. That’s the set, I repeated, but the boy wonder wanted “truth.” Easy to say when someone else is footing the bill, I bristled, and he stormed off, as though I were some stingy philistine who lacked the sensibility to drink from the font of his inspiration. The castle moat took up three rows in front of the stage, cutting into the profits of those earning a percentage. The children’s show on Saturdays and Sundays meant we had to tear down the circus twice a week, weighing down the payroll with three more jugheads. In addition to these imbeciles, four more amateurs took turns as stagehands. Stein demanded more truth and dreamt up two banquets found nowhere in the original. We consumed ten rotisserie chickens per rehearsal, not to mention the overpriced fruit, bread, and vegetables bought at the corner market, only to rot mercilessly in the dressing room. The smell was awful. In the scenes where Lear is expelled from his house by his daughters, a gate—operated by two chains—would slam shut. We spent a week rigging up the contraption. To hell with poetry, Stein wanted action. When we came to the war scene, though I tried my best to convince him otherwise, nothing could dissuade the moron from setting fire to the parapets along the castle walls, covered entirely in styrofoam painted to look like stone. I hired a fireman to be on standby. Stein demanded that, after dying, Cordelia enter nude in her father’s arms. The actress was a cute little thing, and Stein tried everything he could think of to nail her, without success. She had a head on her, that girl. The Sunday before the premiere, the fireman gave in to his hormones and copped a feel of the girl’s breasts. I canned the perv. His replacement only snuck a peek every now and then, and I asked the girl to grin and bear it. After watching a Russian film production of Lear, Stein decided to set the whole thing in the Stone Age. The costume designer had multiple orgasms at the idea and presented us all with an entire collection of sheepskins—he’d wanted bear but settled for sheep. We sweat like pigs, dragging the furry capes around in the summer heat. The curtain rose soon after Carnaval, the air-conditioning was useless, and because they only turned it on when there was a show—mustn’t be wasteful, Horacio, mustn’t be wasteful—two actors ended up in the hospital, further compromising the lead-up to opening night.

worth of the finest wood. The giant logs were so heavy that I was forced to hire an engineer to reinforce the beams beneath the stage. Stage—it was a theater in the middle of a shopping center, a transvestite England. That’s the set, I repeated, but the boy wonder wanted “truth.” Easy to say when someone else is footing the bill, I bristled, and he stormed off, as though I were some stingy philistine who lacked the sensibility to drink from the font of his inspiration. The castle moat took up three rows in front of the stage, cutting into the profits of those earning a percentage. The children’s show on Saturdays and Sundays meant we had to tear down the circus twice a week, weighing down the payroll with three more jugheads. In addition to these imbeciles, four more amateurs took turns as stagehands. Stein demanded more truth and dreamt up two banquets found nowhere in the original. We consumed ten rotisserie chickens per rehearsal, not to mention the overpriced fruit, bread, and vegetables bought at the corner market, only to rot mercilessly in the dressing room. The smell was awful. In the scenes where Lear is expelled from his house by his daughters, a gate—operated by two chains—would slam shut. We spent a week rigging up the contraption. To hell with poetry, Stein wanted action. When we came to the war scene, though I tried my best to convince him otherwise, nothing could dissuade the moron from setting fire to the parapets along the castle walls, covered entirely in styrofoam painted to look like stone. I hired a fireman to be on standby. Stein demanded that, after dying, Cordelia enter nude in her father’s arms. The actress was a cute little thing, and Stein tried everything he could think of to nail her, without success. She had a head on her, that girl. The Sunday before the premiere, the fireman gave in to his hormones and copped a feel of the girl’s breasts. I canned the perv. His replacement only snuck a peek every now and then, and I asked the girl to grin and bear it. After watching a Russian film production of Lear, Stein decided to set the whole thing in the Stone Age. The costume designer had multiple orgasms at the idea and presented us all with an entire collection of sheepskins—he’d wanted bear but settled for sheep. We sweat like pigs, dragging the furry capes around in the summer heat. The curtain rose soon after Carnaval, the air-conditioning was useless, and because they only turned it on when there was a show—mustn’t be wasteful, Horacio, mustn’t be wasteful—two actors ended up in the hospital, further compromising the lead-up to opening night.

The old hag who was lead critic at Rio’s major daily consummated the tragedy. A Shakespeare scholar, the iron lady made her living watching the lowest kind of musicals on stages across Brazil. Though she could forgive cheap comedies, a cruel hostility befell those, like me, who made an effort to take on the canon. She opened her review with my epitaph and closed it decrying public arts funding for allowing such an unfortunate production to see the light of day. A pall fell over the cast. We still had six months to go and a sponsorship contract stipulating a run in São Paulo. The catastrophe in Rio closed to an empty house, we crammed the castle into four moving trucks, and set off for the second leg of our tour.

Fernanda Torres was born in 1965 in Rio de Janeiro. The daughter of actors, she was raised backstage. Fernanda has built a solid career as an actress and dedicated herself equally to film, theater, and TV since she was 13 years old, and has received many awards, including Best Actress at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival. Over the last twenty years, she has written and collaborated on film scripts and adaptations for theater. She began to write regularly for newspapers and magazines in 2007 and is now a columnist for the newspaper Folha de São Paulo and the magazine Veja-Rio and contributes to the magazine Piauí. Her debut novel, The End, has sold more than 200,000 copies in Brazil. Glory and its Litany of Horrors is her second novel.

Fernanda Torres was born in 1965 in Rio de Janeiro. The daughter of actors, she was raised backstage. Fernanda has built a solid career as an actress and dedicated herself equally to film, theater, and TV since she was 13 years old, and has received many awards, including Best Actress at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival. Over the last twenty years, she has written and collaborated on film scripts and adaptations for theater. She began to write regularly for newspapers and magazines in 2007 and is now a columnist for the newspaper Folha de São Paulo and the magazine Veja-Rio and contributes to the magazine Piauí. Her debut novel, The End, has sold more than 200,000 copies in Brazil. Glory and its Litany of Horrors is her second novel.

©Literal Publishing

Posted: May 30, 2019 at 9:28 pm