Literature is More Than a Profession: A Conversation with Eduardo González Viaña

John Pluecker

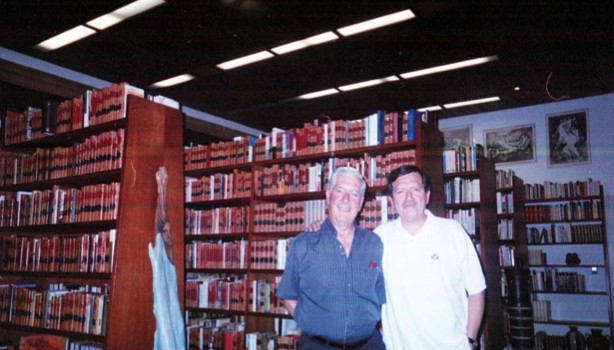

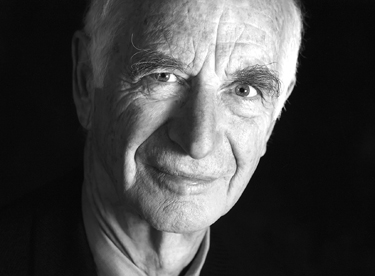

Eduardo González Viaña was born in a small coastal town in northern Peru, and in all his writing the deserts, rivers, animals and shamans of this land find a way to reemerge. This is despite having moved from Peru to the United States in 1990. He came to the U.S. to teach a course on Latin American culture at the University of California at Berkeley, but decided to stay, eventually becoming a tenured professor at Western Oregon University and a naturalized US citizen.

González Viaña is the author of twelve books—among them novels, poetry, short stories and essays. His most recent book, a collection of short stories called American Dreams (translated from the original Spanish Los Sueños de América by Heather Moore Cantarero) revolves around the theme of Latin American immigration to the United States. This mass movement of people is, according to González Viaña, “the largest, most significant since the time when the Jews walked towards the Promised Land.” The characters of the stories include a weary Lady Death who finds a place to rest on an immigrant’s porch, a mystical donkey that crossed the border “illegally” and an elderly Guatemalan woman taking her cancer-stricken son to the U.S. with all their life savings on a search for a doctor. One of the stories from the collection, “Seven Nights in California,” received the prestigious Juan Rulfo Prize in 1999.

For González Viaña, “Literature is more than a profession, it is a mission that converts you into someone committed to your pueblo and to your roots.” Currently, from his home in Oregon, he spreads the word of his mission through his Correo de Salem, a series of journalistic commentaries available on his website of the same name.

I had the opportunity to speak with González Viaña first by phone and then in an extended email dialogue. He was more than gracious, excited to discuss his work and full of insight. What follows is a translation of our e-conversation.

* * *

JOHN PLUECKER: What inspires you to write? And when you are inspired, how do the stories come?

EDUARDO GONZÁLEZ VIAÑA: This morning I realized why I write. I’m pushed to write by an obsession. I’ve spent the better part of the night dreaming about a chapter of the novel I’m writing. Finally, I had to jump out of bed and come to the computer. I’ve been writing without stopping for an hour and I have transcribed some of what I was dreaming.

It always happens to me this way. In today’s case, it was a novel that I’ve spent several months on without being able to deal with any- thing else but the novel itself. I was afraid to write in this more journalistic style, because I thought that it would prevent me from reaching the state of concentration that I need. At times, I’m not even able to respond to emails. Recently, just in this moment, I’m able to answer the question that you asked me. . . and I think that I cannot go back to bed despite the fact that it has only just turned five o’clock on this Sunday morning.

J. P.: You write essays, short stories, poetry and novels . . . perhaps other forms as well of which I am not aware. What draws you to each one of these disparate forms? Do you prefer one over the others?

E. G. V.: I would like to be writing short stories all the time. . . if I was the complete master of my time. I am a university professor, and because of this, I have to dedicate part of my life to that work. But yesterday, I was asking myself what I would do if I won the lottery and I said to myself: write short stories.

To write novels is practically the same, only the obsession lasts longer and it consumes you more.

I write essays, poems and journalistic articles because of the necessity to express myself. Writing is the one thing that I do with less clumsiness.

J. P.: You were born, raised, and have lived the majority of your life in Peru. How does the writing you did in Peru differ from the writing you have done since coming to the U.S.? Are you pleased with the changes?

E. G. V.: Writing is communicating with someone. In the United States, I write for an international public. I cannot take for granted the references to space, time or history that I allude to when I write in Peru. Not even the language is the same. Everything is transformed by the magical perception that you are getting to know your new reader. It’s as if you were reading over the shoulder of someone that is reading your work.

J. P.: You have said that you have decided to stay in the United States to write and to work. What influenced your decision to do this? What do you think you have gained and what has been lost?

E. G. V.: In 1990 I was invited by the University of California at Berkeley to be a Visiting Professor for one semester. At the end of this term, they invited me back for another year. And it was the same from then on. . . The moral here is that I should not be invited for coffee, because I could stay for dinner.

My decision to stay in this country was influenced greatly by the political situation of my country. During this decade, Peru was governed by an infamous dictatorship. Perhaps it was the most hateful of the century because they made use of all the technological means available to them to enter into the lives of all its citizens.

What have I gained by staying? The complete conviction that I am a writer and that I must live as such. What have I lost? Perhaps some local slang or regional slang in my Spanish. I must write and speak a more Standard Spanish. . . but I also have a feeling of freedom that I have never experienced previously.

J. P.: I notice that Porfirio, the donkey from American Dreams, reappears in your new novel, Dante’s Corrido. What has Porfirio come to mean to you in your writing? Who is this donkey?

E. G. V.: Perhaps Porfirio is an expression of my nostalgia. . . I am from the north of Peru, a desert in which we only have rivers in the summertime. Donkeys are very common there. In some villages, the image survives of a man meditating while seated beside a donkey. I have always thought that the donkey was also deep in thought. . . This is what I have brought from my land.

J. P.: Many of your stories have a magical element to them. I am thinking in particular of “Shadows and Women” from American Dreams. What is the role of the fantastic or the magical in your writing?

E. G. V.: I know where all of [the fantastic in my work] comes from, but I cannot explain what its role is because it is nothing I have planned. It is an unconscious process. It also comes from the coastal North of Peru where there are whole villages full of brujos and where pre-Hispanic cosmogonies still persist. Although I am an “educated Peruvian,” all of this has entered me through my pores.

At one time, I was an assistant to a brujo. Because of this experience, I wrote a book. The brujo asked me why I had returned to Peru. (At this time, I was studying in Paris.) I responded to him that I returned simply because I returned. No, he told me. Your hill has called you back.

And that is true. There is a hill near my village that is the oldest one in that area. My parents are now deceased. This hill will last. I must have something from this hill. Don’t you think?

J. P.: How do you find your own personal story emerges in your writing? Do you see any of your work as autobiographical?

E. G. V.: All of my work is autobiographical. I cannot write except starting from the experiences and the dreams that make up my daily life.

J. P.: Many of your stories are written from a first person perspective. Do you prefer a particular voice in your writing?

E. G. V.: That first person is autobiographical. Sometimes I long to make an exasperated confession, and so I do it in first person. I am thinking of the story “Death Confesses” from American Dreams. Death speaks with me. She’s very tired from all the work that my country has given her. She doesn’t enjoy taking people away, except in effect she takes them away without taking them away completely. When the army or the police enter a man’s house, they take him by force, dragging him to their barracks, they torture him and on the following day, they say that that same man has disappeared. I had to tell what has happened, make it known and condemn it. My denouncing it has broken the structural circle of the story, but I felt good.

J. P.: Do you consider yourself a Latin American writer living in the United States, a Hispanic author, a Peruvian or Peruvian-American writer, or perhaps something else? How have your experiences coming to this country and deciding to stay here influenced your writing?

E. G. V.: There are many people that spend their time debating that problem. Many very interesting books have been written about that. I do not have much time to dedicate to that discussion; it seems to me to be a little metaphysical. I only write. I accept with gratitude all the names that are given to me.

J. P.: What are your thoughts and feelings on the process of translation? Do you find that anything is lost in the process? Do you take an active role or do you view the translation as somehow separate from the original work?

E. G. V.: Translation is a fascinating process in which I feel tremendously happy to be included. Translation is about much more than the transfer of one language to another. In addition, it is communication between two different cultural worlds. I am always interested to know how willing the other side of the world is to accept the flight of my metaphors. What’s more, the translation can suggest a change to me in the original version. When my publisher, Arte Público Press, asked me to suggest a translator, I tried out a few. What they presented me with was correct from a formal point of view, but not excellent. Finally, I found Heather Moore, a poet in English, and I discovered that she could go far beyond the mere meaning of the word and recognize the rhythm of my prose. Hers is really a very beautiful translation.

J. P.: What contemporary writers of the Americas do you find inspiring or influential personally?

E. G. V.: At one time, I left my land never to return again. I packed into my suitcase all the clothes I needed and two books. There were the complete works of Pablo Neruda and Jorge Luis Borges. I don’t know if these authors are reflected in my work, but I’ve learned with them the happiness of reading and the alchemy of writing. I can also indicate names of prose authors like Juan Rulfo, William Faulkner, Gabriel García Márquez and Alejo Carpentier.

J. P.: What was your family like growing up in Peru? Academic? Literary? Did they help you to find your voice as an author?

E. G. V.: My father was a great lawyer and in addition the owner of a country estate where rice was grown. . . At fifteen years old, I wrote my first short story. It dealt with the abject exploitation of the peasants in the sugar haciendas.

When my father read it, he said, “It seems that you have chosen to be a writer and also a redeemer. I say one can’t live from these things, rather one dies from them in this country.”

“Thank you, Dad, for saying this to me. . . One always has to pay a high price in order to be happy.”

“I am proud of you, son, and you will always be able to count on me,” he told me. After this, he picked up a little bit of mud off the ground and put it on my face.

“Kiss the earth,” he told me, “and love it because you are going to live from it.”

My maternal grandmother read Dante to me in Italian when I was only ten years old. According to her particular theory, children can understand all languages. I always wanted to write a novel using the structure of the Divine Comedy. I’m very happy for my family that I’ve been lucky enough to write this novel [to be published as El corrido de Dante in Fall 2006].

J. P.: Do you ever write in English? Would you ever attempt to write in English or do you prefer to write in Spanish?

E. G. V.: I have written poems in English a few times. I have still not considered the possibility of writing a short story in English. First, I am going to finish saying what I have to say in Spanish. And then, I’ll see. . .

J. P.: What are you working on now?

E. G. V.: Today, I am living one of the happiest days of my life, because today is my birthday and last night I finished writing a novel that has been my obsession. Its main character is César Vallejo. I want to spend at the very least three days without obsessions. . .even though I am already tempted to go get the recorder and dictate a story about immigrants.

* Images by Ivonne Saed

Posted: April 4, 2012 at 3:24 am