Mañana Forever? Mexico and the Mexicans

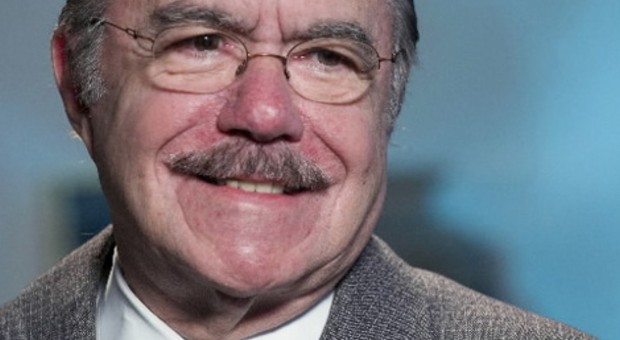

David D. Medina

Título: Mañana Forever? Mexico and the Mexicans, El Colegio de México, México, 2011.

Título: Mañana Forever? Mexico and the Mexicans, El Colegio de México, México, 2011.

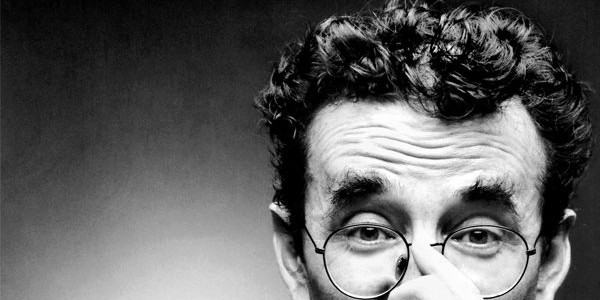

Autor: Jorge G. Castañeda,

Mexico. So far from God and so close to Jorge Castañeda. The unflattering portrait of Mexicans that Castañeda paints in Mañana Forever? Mexico and the Mexicans will certainly upset many.

But the purpose of this compelling book is not to tear down Mexicans. It is an attempt to explain why Mexicans are the way they are and what they need to do to move their country forward, to a modern nation that respects the law and diversity, and enjoys a civil society.

According to this leading Mexican scholar, Mexicans are so individualistic that they stink at soccer, prefer houses to high-rises, do not engage in civic or charitable activities, see themselves as victims, distrust foreigners, and attend Mass much less frequently.

The theme of the individualistic, untrusting Mexican has been examined by many, including Mexican poet Octavio Paz and American journalist Alan Riding. Castañeda, however, offers to go deeper into the past to explain how Mexicans adopted these traits that once may have been useful and now are an obstacle to the country’s progress.

Castañeda reasons that there is a historical explanation for this national character. For the past 500 years, Mexicans have suffered a series of overbearing government control: first the Aztecs, then the Conquistadores, followed by colonial rule and 75 years of authoritarian rule by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). “This Hobbesian behemoth . . . has simply never allowed civil society to flourish, and absent an organized civil society, people fend for themselves,” observes Castañeda.

This iron-fist control has lead to some very serious consequences for Mexicans. Fearful of leaving themselves vulnerable and being “screwed” once again, Mexicans avoid conflict, direct confrontation, open debate, and taking sides—all of which are necessary for a democracy to function, Castañeda explains. Disrespect for the law is also a direct descendant of colonial rule, when the Conquistadores ran their own show and never complied with the king’s edicts.

“…By maintaining the colonial era’s tradition of ignoring the law, Mexico was perpetuating a birth defect that would plague it for nearly two centuries,” says the author. Ignoring the law has led to corruption, organized crime, cynicism, and an informal economy that operates under the government’s radar to avoid paying taxes.

There is hope, though. Castañeda believes that if Mexicans can alter their attitude and begin to believe in the rule of law, things may change for the better. “They can metamorphose into something new, different, and marvelous.”

As proof that change is possible, he points to the Mexicans who have crossed the northern border and transformed themselves into law-abiding residents. Mexican immigrants living in the United States rarely break the law and, in fact, are responsible for a “remarkable drop in crime,” Castañeda asserts.

Written in an authoritarian voice that is, at times, self-serving, the book often lapses into convoluted, academic prose, littered with a dizzying array of facts and statistics. If you can withstand these mind-numbing passages, the book offers insightful information and analysis about a country that must overcome serious challenges in its endeavor to become a truly democratic, modern nation—a tall order to fill, to ask a nation of people to change a trait that has been embedded in their character for centuries. Buena suerte, Mexico lindo.

Posted: June 10, 2012 at 4:15 am