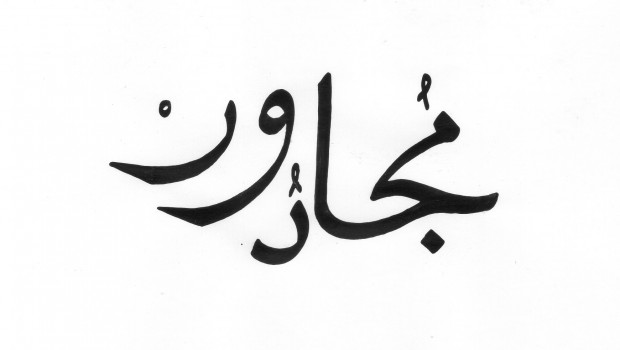

Poetics of Wonder: Passage to Mogador

Alberto Ruy Sánchez

*Chapter VII: On Libraries and Those Who Inhabit Them

Translated by Rhonda Buchanan

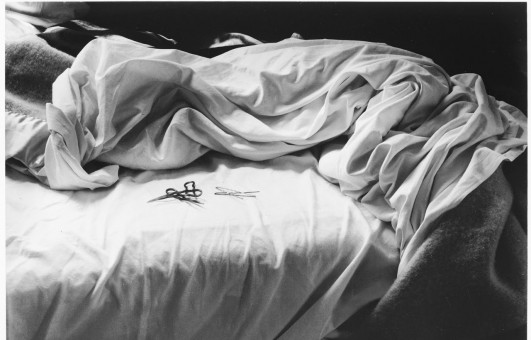

Image by Caterina Camastra

Introduction

In 1975, the Mexican writer Alberto Ruy Sánchez was a graduate student living in Paris, where he and his wife Margarita de Orellana were pursuing doctoral studies. The fall semester ended, and with time on their hands but little money to spare, they decided to take a trip to Morocco, a place that fit their budget and offered a warm escape from the cold winter in France. At that time, Ruy Sánchez had no way of knowing that the journey to Morocco would become a rite of passage, an initiation into a culture that would forever change his life and his future literary career. Upon seeing the Sahara for the first time, his childhood memories of the Sonoran Desert came rushing back to him, and in his imagination he began to erect un puente de arena, a bridge of sand that united Morocco and his native Mexico. In the souk, the colorful ceramic plates and tiles reminded him of the Mexican Talavera pottery, and the Berber rugs and tapestries evoked the intricate textiles of the Chiapas. But of all the intense moments he experienced in Morocco, the one that would have the most profound impact on him was his visit to Essaouira, a walled city on the Atlantic coast whose ancient name was Mogador. From the moment he first laid eyes on Essouira, this city has continued to obsess and seduce him like an inaccessible woman who extends with her gaze the invitation to explore her labyrinthine streets and enter her secret gardens.

Soon after that first journey to Morocco, he began to construct a quintet of novels that take place in Mogador and explore the many facets of desire: Los nombres del aire (1987, The Names of the Air), En los labios del agua (1996), Los jardines secretos de Mogador: Voces de tierra (2001, The Secret Gardens of Mogador: Voices of the Earth, 2009), and La mano del fuego: Un Kama Sutra involuntario (2007, The Hand of Fire: An Involuntary Kama Sutra). Like the last finger of the Jamsa, a fifth book, Nueve veces el asombro: Nueve veces nueve las cosas que dicen de Mogador (2005), serves as a companion to the other four novels and offers the reader a “Poetics of Wonder,” or a primer for approaching the inaccessible “city of desire.”

Hassiba, the protagonist, shares with her lover a series of intimate lessons regarding the paradoxical and wondrous nature of Mogador. The novel’s subtitle, Nueve veces nueve cosas que dicen de Mogador (Nine Times Nine Things They Say about Mogador), reflects the contents of the book: nine chapters composed of nine texts each, 81 flashes of insight that Hassiba will reveal to her lover, and in so doing, to the reader as well. In Chapter 7 of Poetics of Wonder: Passage to Mogador, Hassiba describes the wonders that may be found in the Libraries of Mogador.

***

Fifty-five

It stands to reason that the libraries of Mogador are evolving extensions of what has been inscribed on the skin of its inhabitants since ancient times. And it is no coincidence that tattooed hides protect the fragile parchment of books lining their shelves. Nor is it inconceivable that libraries and music share a common bond: their sheets are masterful metamorphoses of the skin.

Fifty-six

In Mogador, every open book is always ready to dance inside us. A blink of the eye or a brush of fingers over its pages is all it takes for it to penetrate us swiftly with joy. Once inside, each book meanders through the channels flowing within us and settles, in its own way, in unexpected regions of our flesh. In some they become discernible love handles around the waist, while in others they are converted to muscle, ready for action. And there is always someone who feels that books enhance their sex in thickness, finesse, and depth. In his indispensable Anatomy of Melancholy, the 17th century philosopher Robert Burton provides evidence that the consumption of many books may lead to reflective sadness. Their weight in the blood and the color of their ink increases black bile in avid readers, while the bile of those who limit their reading to only one book has a tendency to turn yellow, the bodily humor of anger, perhaps because they absorb more paper than ink. Quick-tempered dispositions nourish themselves exclusively with those unique books revered as sacred by certain vicious circles.

Fifty-seven

Each new book is considered a metaphor of a birth in Mogador. Or the announcement of the welcome arrival of a foreigner. And the quantity of volumes preserved in the city is always a multiple of the number of its inhabitants. This is why each day one of the librarian’s greatest responsibilities is to maintain that precious proportion whose fluctuations are sensitive to increases and decreases in population, emigrations and wars, as well as euphoric reproduction and plagues.

Fifty-eight

The opposite calculation may also result: when a plague of moths or other insects enters the library and devours books, people consider this a bad omen, a sign of imminent wars or catastrophic epidemics. They say, with a bit of pride, and some chagrin, that Mogador is the only city in which many of the most tragic scenes of its History may be traced back to something that happened in the library.

Fifty-nine

They say that in certain enchanting sections of the library of Mogador, if two kindred books are left at night, side by side, three of them appear at dawn, and that librarians cultivate those “nights of blissful paper” like gardeners tend their flowers. And they take measures to prevent conflicts between opposing books. In the placement of books in the library, they aim to clarify that substantial differences may occupy the same shelf without necessarily sharing the same ideas.

Sixty

They say that healthy cultural promiscuity, and the natural hybridization among books, is quite apparent in the library of Mogador, whose strength stems from that incessant fertile diversity. At one extreme of the building, even the sacred books of Jewish, Christian, and Moslem faiths coexist by observing the art of distances, thus forming a perfect arrangement whose harmony can never be compromised by the fundamentalist prohibitions imposed by one hallowed book.

Sixty-one

They say the books in this library have very strange powers, and that whenever a book from Mogador is opened, somewhere in the universe a star explodes, or in northern Canada two hundred million butterflies begin their epic migration of three thousand miles to spend winter among the extinct volcanoes of Mexico, or the tides go out, or goats climb the argans, those Mogadorian trees that patiently guard the entrance to the Sahara, or in an attic of a forgotten corner of Bosnia-Herzegovina, a genius composes a symphony dedicated to the beautiful library of Sarajevo, destroyed in the war, or perhaps in a New York studio, a prolific Anglo-Mexican-Catalan sculptor engenders extraordinary bronze creatures: an amazing new species of limulus, those intriguing horseshoe crabs described by scientists as “living fossils,” which openly defy Darwin’s theories, having survived without changing or adapting for two hundred million years, and reproducing every spring on the beaches of New England and the peninsula of the Yucatán.

Sixty-two

Relegated to the shadowy corners of the library are certain books that no one in Mogador has dared to open for two centuries. An eerie glow emanates from them, seasoning the air with a luminous aura and filling the surroundings with the smell of sulfur. This has been going on since the last plague of locusts assaulted the city, consuming every living thing. After crossing the Sahara for several weeks with nothing to eat but themselves, Mogador was the first inhabited place they encountered, thirsty and ravenous. According to The Concise and Abridged History of Saharan Migrations, for the locusts as well, Mogador was and is the city of desire.

Sixty-three

They say that in Mogador books about animals, from the most ancient to the very modern and highly illustrated bestiaries, are kept in cabinets behind bars because at night beasts can be heard trotting through the books, from one side of the shelves to the other. Books on birds come unbound more quickly than others, making it necessary for their leaves to be sewn two or three times, while those concerning oceans and rivers are more often plagued by mold. Treatises on mining, such as the famous Re Metalica, are inclined to transform themselves into treasures, thus their study requires speculative readers who are somewhat miserly and unrelenting. The pages of adventure books turn faster than those of others. Invisible hands sprout from volumes of poetry, touching the reader deep inside the body. The pages of books on ethics, canonical law, and theology screech and their seams expand, at times concealing letters. Books by mystic authors open without anyone touching them. And those books regarding Mogador have the good fortune to be loved always with a passion that engages all the senses, with a growing adventurous desire, because, among other reasons, the books about Mogador extend far beyond their pages and continue writing themselves like dreams on the skin and flesh of those who read them, and even those who merely touch them. Perhaps without knowing it, those readers from long ago and those yet to come, are the ones who inhabit these books.

***

About the Author

Born in Mexico City in 1951, Alberto Ruy Sánchez is the author of books of fiction, essays, and poetry, which have been translated into many languages. He is best known for a series of novels, which take place in the Moroccan city of Mogador, and explore the nature of desire: Los nombres del aire (1987), En los labios del agua (1996 ), Los jardines secretos de Mogador: Voces de tierra (2001), and La mano del fuego: Un Kama Sutra involuntario (2007). In 2005, Ruy-Sánchez published a companion book to the Mogadorian tetralogy entitled Nueve veces el asombro: Nueve veces nueve cosas que dicen de Mogador (Poetics of Wonder: Passage to Mogador; forthcoming White Pine Press, 2014). Since 1988, Alberto Ruy-Sánchez has been the Editor-in-Chief of Latin America’s premier editorial house, Artes de México, which has received more than 100 international awards. In 2000, he was decorated by the French Government as Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, in addition to many other prestigious honors. For more information, visit the author’s website: www.albertoruysanchez.com.

About the Translator

Rhonda Dahl Buchanan is a Professor of Spanish and Director of Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of Louisville. She has published critical studies on Latin American fiction, as well as translations, including: Limulus: Visions of a Living Fossil by Brian Nissen and Alberto Ruy-Sánchez (Artes de México, 2004), The Entre Ríos Trilogy: Three Novels by Perla Suez (University of New Mexico Press, 2006), Quick Fix: Sudden Fiction by Ana María Shua (White Pine Press, 2008), and The Secret Gardens of Mogador: Voices of the Earth by Alberto Ruy-Sánchez (White Pine Press, 2009), which was supported by a 2006 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship. Poetics of Wonder: Passage to Mogador will be published by White Pine Press in 2014.

Posted: February 18, 2014 at 12:04 am