Patricia Sicardi, a road to Cadaqués

Fernando Castro R

“You have to give it your all.”

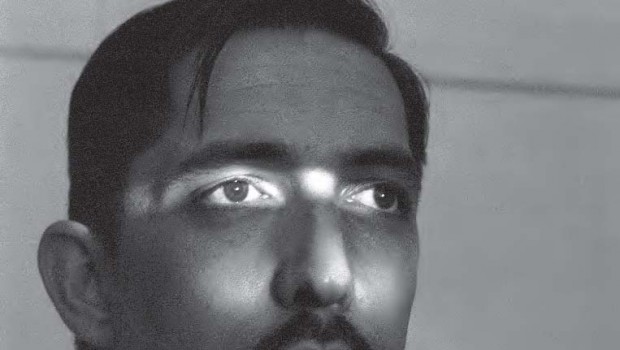

Patricia Sicardi (1948-2024)

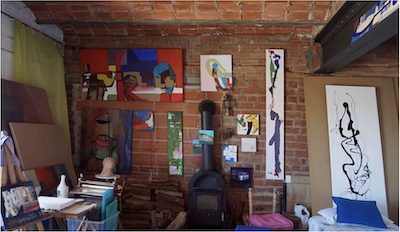

Patricia Sicardi’s studio, 2018 (photo by the author)

By the time Patricia Sicardi moved to Cadaqués in 2005, Salvador Dalí had been dead six years. He was not the only one who had animated the once quiet fishermen cove, but he was certainly one of the artists, architects, musicians, writers, and singers who contributed to the lure and lore of the chic town it became. Marcel Duchamp played chess at Café Melitón. Dalí drove around on his old Cadillac with Carlos Lozano, his androgynous Colombian toy boy. Gabriel García Márquez turned a nasty tramontana wind into a character in a short story. Patricia was forty-nine years old when she arrived, and she too became part of the cadaquesencs scenery.

However, Cadaqués was not Patricia’s first stop in Spain. In the year 2000, she had first arrived in Barcelona. Flashback twenty years: during her formative Buenos Aires years, as most starting artists often do, she had experimented with different styles of painting. For her, that 1980-2000 period was one of enthusiasm and discovery. In her 1990 oils the medium enthused her to paint with the eyes of Cezanne, Van Gogh, Hopper, et al. Noteworthy is Playa Grande (1994), depicting a row of cabins in an uninhabited beach—a sequence of yellow, blue, and orange polygonal roofs against an intense sky that is neither auspicious nor ominous, only the backdrop of the horizon. Playa Grande is an oil that the alert observer will not connect with any artist other than its author. Tendida en las arenas (1993), on the other hand, is an amorphous, turbulent landscape, more like the artist’s state of mind than the sea, the beach, or the sky. From that same year is Rostro (1993), in which a barely discernible profile amidst the colorful impasto suggests a reflection about color, form, and the materiality of paint.

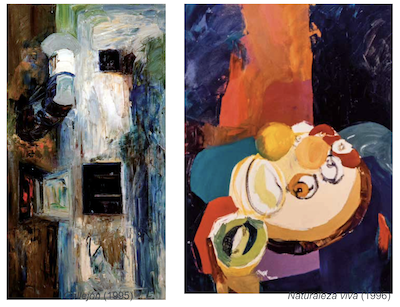

This thick expressionistic style of painting is one to which Patricia would return during several periods of her life. It is present in the grim and very urban Callejon (1995) —a window to a somewhat dark and monochromatic day, maybe in winter, facing the façade of a damp gloomy apartment building. Naturaleza viva (1996) has a different aesthetic. It is a still life, somewhat Cézannesque and/or Matisse-like, less introspective, with tamer forms than Rostro (1993). The tray where the fruits rest irradiates light, inviting the viewer to participate in the feast, to taste the succulence of the melon and the peach. With these and other works in her portfolio, Patricia began her pilgrimage to Europe at the start of the 21st century.

Barcelona is a city whose abundant modernismo (Art Nouveau) hangs on to beauty, while its modernity dismisses it. Patricia’s Barcelonian work attests that the city of Miró, Tápies, Gaudí, and modernista architecture impacted her deeply, and that what she saw was evidently educating how she painted. Her palette from 2000 to 2005 is abundant in blues, reds, oranges, ochres, and greens. Patricia adopted the forms she found in the streets of Barcelona and transformed them into geometric compositions, with varying intensities of light and color. La Rambla, Barcelona 2002 and Plaza Real 2002 are paintings that show that hybrid predisposition. The ebullience of the city seduced the artist into figurative representation of her surroundings.

In 2005, Patricia moved to the small coastal city of Cadaqués, a Mediterranean town with white houses, famous for having had among its denizens Eliseu Meifrèn, Salvador Dalí and his entourage, the Pitxot family, Pablo Picasso, André Derain, Pablo Casals, Duchamp, Man Ray, Maria Martins, Albert Rafols-Casamada, Maurice Boitel, Henri-Francois Rey, Walt Disney, René Magritte, Richard Hamilton, et al. They were all gone in the 21st century, but the city became the epicenter of Patricia’s artistic activity, whose territory included the south of France, Italy, London, as well as Mexico, Buenos Aires, and the United States. She showed her work in art galleries such as Magdalena Baixeras in Barcelona, Pou d’Art in Sant Cugat del Vallès, Shad Gallery in Toulouse, Studio Mitti in Milan, Samara Gallery in Houston, Patrick J. Domken in Cadaqués, and more. She herself opened the gallery SiArt in 2005, and in 2011, the Rivera-Sicardi Gallery, both in Cadaqués.

The cadaquesencs landscapes that enticed Dali for decades, did the same for Patricia, but at a time when the spell of Surrealism had long dwindled. Nevertheless, there is a curious similarity of style and content between the early 20th century Cadaqués townscapes Dali painted in his pre-Surrealistic period and the ones Sicardi painted in the 21st century.

Noche de ronda (2006) is a most horizontal painting of blue waters sprinkled with white boats rendered with a mere stroke of impasto; whereas Solo (2006) is an extremely vertical painting dominated by the white geometry of a boat’s triangular sail. The series of vertical doors that Sicardi painted around 2002 show her ever-changing commitment to mimetic painting, from Puerta #22, mostly disfigured by the impasto, to Puerta #297, with its blue and yellow discernible up to the steps.

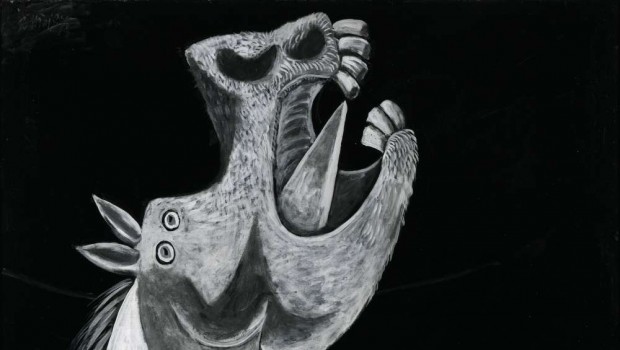

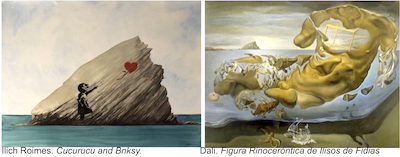

Cucurucu (2010), deserves special mention because Patricia undertook the challenge of painting the iconic islet that protects Cadaqués Bay, and which many other artists, including Dali himself have addressed. Patricia‘s is certainly not a placid seascape in which to imagine a regatta over Mediterranean blue waters, but a disquieting sea perhaps at a moment of a tramontana. It is perhaps the most disturbing work ever painted by her: Cucurucu as a gargantuan shark fin.

In the second decade of the 21st century the pendulum swung again taking Patricia to an abstraction that is occasionally geometric and at times unabashedly gestural. Abstracción (2011) is a pivotal work because it combines both tendencies: the red rectangular insinuation and the blue and brown explosive stains, respectively. Her more gestural works, like Huída (2015), echo Miró’s colors and white pictorial space, and her drips may be a nod to Twombly whose works she may have absorbed in Houston’s Cy Twombly Pavilion. Patricia’s 2016 Houston exhibit at Samara Gallery clearly showed her gestural staying power.

Hans Hoffman could have become an Informalist artist had he not left Europe for the United States where he ended up —according to Clement Greenberg— as an “unclassifiable” abstract expressionist. “If I only have one style, I am dead as an artist,” Hoffman said once. That could have very well been Patricia’s motto—with the understanding that she came from another conjunction of influences and contexts. Moreover, she did not have to get involved in that gratuitous quarrel against easel painting and figuration. Nonetheless, Hay lugar para todos (2010) shows incredible formal and chromatic coincidences with Hofmann’s 1962 Autumn Chill and Sun. Unlike the latter, however, Lugar para todos is not merely a calculated exercise but a transference onto the canvas of a mental state from Cadaqués. It is another one of those works of synthesis that Sicardi arrived at after long pictorial wanderings.

While in her later years Patricia was still moving freely between the calculated forms of geometric abstraction and the spontaneity of gestural abstraction, it is nevertheless, also true that she occasionally gave into the figurative temptation. Her work was in constant oscillation. For some critics, her lack of commitment to a single style is unsavory; for others, it is salutary. Gerhard Richter, one of Germany’s greatest living artists is well-known for working in two distinct and different styles, one very abstract, and another one, photorealistic. Richter has famously stated: “I like everything that has no style: dictionaries, photographs, nature, myself and my paintings. (Because style is violent, and I am not violent.).”

Like Richter, Patricia had several styles of painting —which for many (including Richter) is tantamount to having no style. Two years before her demise, Patricia Sicardi published a retrospective book of her life and oeuvre. It painted for the reader a path lined up with shapes, walls, colors, skies, forms, boats, ideas, doors, and moods whose final destination is Cadaqués.

Fernando Castro es artista, crítico y curador. Estudió filosofía en la Universidad de Rice con una beca Fulbright. Es miembro de la comisión técnica del FotoFest y del consejo consultivo del Center for Photography de Houston. Editor y colaborador de las revistas Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magaziney Spot.

Fernando Castro es artista, crítico y curador. Estudió filosofía en la Universidad de Rice con una beca Fulbright. Es miembro de la comisión técnica del FotoFest y del consejo consultivo del Center for Photography de Houston. Editor y colaborador de las revistas Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magaziney Spot.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad.

Posted: September 3, 2024 at 8:07 pm