Pride Parade

Desfile del orgullo gay

Teresa Di Tore

“Where is the float?” I ask as I look around the skyscrapers surrounding us.

“It says B-4 and that means…right on the left.” Maria looks at the wrinkled piece of paper with a poorly printed map on it. We turn around the block and see our organization’s float. I had joined the Families and Allies group three years ago, when my son came out as gay. I’ve been marching at the Pride Parade every year since then, but this was the first time a family member came with me.

“It looks beautiful!” says my sister Maria, staring at a plywood structure sitting on a pickup truck. The circle shows the outline of Houston’s landscape against a beaming rainbow. I nod thinking of the many hours we spent decorating the float. So many parents who’d just discovered their kids are gay and don’t know how to handle this new situation are here today to show their love and acceptance. Maria laces her slim, but strong dark arm around mine to show me she’s here for me. Her brown eyes are lively moving from face to face, eager to meet the other parents.

“When do we march?” asks Joe’s son. He’s wearing a black leotard and t-shirt and a brightly colored tutu.

“We’re number 100,” Sophie says rolling her blue eyes and waving a huge rainbow feather fan.

“Aw, you guys, don’t you love hanging out with your parents?” asks Sophie’s mom as she hugs her daughter and laughs. She’s been part of the parade for three years now, the same as I have. But my son is not with me. He told me earlier that he’d be in the crowd watching us march.

“He’ll see me now,” I say to Maria crossing my arms in front of me, “and he’ll believe that after three years of trying to understand him, I’m now showing the whole city that I love and accept him.” Maria gives me a sad smile, looking down. She was with me when family members told me it just wasn’t right to be gay. She heard the reproaches and felt the guilt they tried to land on me because they thought I was indulging my son into being immoral.

People are hanging around the float, some leisurely walking; others sitting and visiting. Bottles of water are being passed around. The afternoon is ending, but the heat is still strong and many have been here for several hours.

“We forgot the signs!” says Joe raising his arms in alarm, “Can somebody run to our office and get them?”

“We can’t leave now. The parade starts soon,” says Linda resting her body against the truck. It is hot and sticky, but the sun is beginning to go down and the promise of shade makes everybody sigh with relief. Joe, Linda, and the other organizers have spent the whole day working to make this happen.

“Besides, who wants to walk by the gay haters by the entrance?” says Linda opening her eyes wide. “Even the most seasoned father can’t stand the verbal assault of those guys.”

Maria finds my arm and squeezes it gently. “Can they hurt us?” she’d asked when we passed the entrance earlier this afternoon. I bite my lower lip. I can’t answer that.

“There’s a piece of black cardboard here!” says Linda. “If I can find a knife, I can cut it into pieces to write our own signs. I have white wax pencils that we used on the float. It should work.”

I look at the blank piece of cardboard. “What should I write?” I ask Maria. I touch the surface of the paper with my long fingers, trying to figure out how to express all my feelings in this sign. I see the lines on my hands, my wedding ring. “I fear,” I say to myself, “that my son will be physically attacked.” I swallow hard and I write quickly in bold letters, pressing my fingers hard till they hurt. This is the best antidote I can think of. I want my son to see my sign in the crowd. I want him to see my words, to see me, publicly loving him. I exhale my pain and look around me.

I see Peter, his white hair plastered to his head in the June heat, quietly leaning against the truck, hugging himself and watching the others writing their signs. “Do you want to write a sign?” I ask him offering my wax pencil. My hands are slightly trembling. He shakes his head no and looks away without a word. Peter has been coming to our meetings for less than a year now and he’s not ready. I know it because in my first year I felt overwhelmed by the parade, worried about who will see you marching and judge youHow . I see Peter’s wife talking to him. She is carrying a “Proud Parent” sign, but he says no to her and she gently squeezes his shoulder and lets him go. She joins other parents in the group.

“Let’s go, let’s go!” prompts Joe and we all start walking down Houston’s streets. A banner painted with our logo precedes the float and I walk right behind it to the left. I lift my sign up, right above my eyes so that I can see the crowd. “Love you, mom!” “Way to go!!! Woo, Woo!!” people in the crowd cry as the pitch keeps going up and up until it dies. More waving of the sign and it all starts again. I try to look and smile at them. They are mostly young adults, kids to me, like my son. He is somewhere in the crowd, watching me and all the other parents with me, telling our kids we love them and in spite of our fears, stand by their side.

I look at the hundreds of young faces in the crowd and I wonder what they see. A middle aged, slightly overweight mother with short highlighted hair and dark framed glasses smiling at them. How good am I to hide my fears, the voices in my dreams? I still remember my aunt saying, “There are no homosexuals in our family.” “He’s just too young, he’s experimenting,” my cousin said. “You raised him well; he’ll get over it. You’ll see.”

with short highlighted hair and dark framed glasses smiling at them. How good am I to hide my fears, the voices in my dreams? I still remember my aunt saying, “There are no homosexuals in our family.” “He’s just too young, he’s experimenting,” my cousin said. “You raised him well; he’ll get over it. You’ll see.”

I used to look at the gay people in my Friends and Allies group and think that my son was not like them. We were not like them. This sense of otherness remained with me until I accepted that someone very much like me, as much like me as anybody will ever be, is gay. I know it’s hard to understand, to comprehend that deep differences exist with those we so profoundly love. But the moment my son told me he was gay, I was thrown into this reality. I could not deny, find excuses, and refuse to see for long what life was like for him. I was a part of it because he was a part of me. A parent begins to see. All these kids, all the faces in the crowd are as much my children as their mothers’. We are all the same, equal in our needs, desires and love. Different only in form: all the painted faces, the brightly colored hair, the awkwardly daring poses, the bold costumes, the defying sexual innuendos, are there to tell us, “See Me. I exist and need love”. How can a mother say no? I see the phones aimed at my face and wonder where my picture will show up. I think of my friends. Are they in the crowd? Do they see my sign? These are the fears they can’t see. I blink to clear my eyes, and all I can see now are the kids.

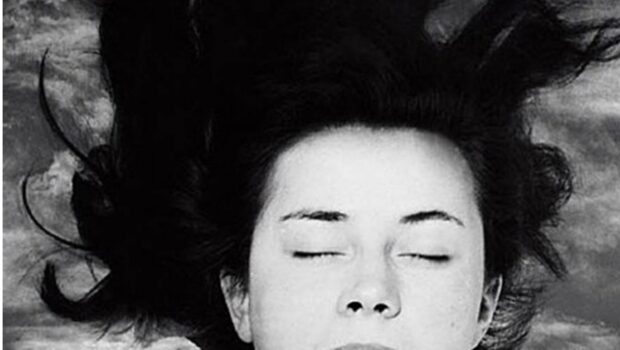

A fence separates the crowd from those marching. A young woman leans against it far out, extending her arms, eyes fixed on my face, offering the nicest bead necklace she has. The one made of big white plastic pearls, with a big silver pendant in the shape of a heart. I break the line and go up to her, lower my sign and let her put her gift over my head. “I love you, mom,” she mouths and I smile as brightly as I can knowing deep inside that there is a mother out there that she is talking to, yearning for, and missing terribly. I let that necklace sit against my chest with its weight of love and go back to my place behind the banner thinking of my son.

I realize I don’t know where he is, what side of the road, if he will see me or not. I did not hear my phone that is safely kept in a bag, hanging from my neck. I missed his text, I think, and start searching in the crowd. And as I do this, I wave my sign and the kids start with renewed vigor to call me mom, their moms, all the moms that we embody in this parade. I smile and the hands go up. They want to slap my hand in a ‘give me five’ salute, to honor me for honoring them with my support. I slap these young hands with all the love I have thinking that in our human experience, we are all one.

I can’t ignore the hundreds of kids standing at my side, waiting to see us all march to celebrate Pride. I think of all the phones and wonder who will see my face. Who will continue being my friend and who will hurt me with their words. My arms are beginning to feel really heavy, but I raise my sign high again, and as the crowd cheers, I see a photographer inside the marching perimeter with a tripod and a serious looking camera. He’s snapping pictures of me and my sign. I try to smile, ignore him, and concentrate on the kids. “Is that one of the local papers?” I murmur to nobody in particular. I start to notice all the cameras that are aimed my way. People in the crowd get excited and out come the phones. Who will see me? I wonder. What if some of my friends see my face? The ones I have not told yet, the ones who don’t know. What will they say? Will they be surprised? Will they talk to me again? Will they invite me to their parties? Will they pity me, pray for me? How will I react to hurtful comments? Gently? Snappy, not giving an inch? Will my face be all over social media? Will people I work with know? And the relatives? Oh, God! The ones I haven’t told because I know they’ll be nasty. And the ones that are nice, but will pity me inside. I feel the sweat going down my back and I remind myself to hold my chin up, to be proud, and to show what’s in my heart no matter what. Don’t drive yourself crazy, I warn myself and smile to the crowd. There, cameraman, take the picture of this smiling mom.

I can’t see my son in the crowd and we’re almost in the last block. I strain my eyes, I want to find him, but my arms are achy and my fingers feel chapped. One more turn and we’ll reach the end. We pick up speed. I raise my head again and rush to make a turn. The crowd gets louder, my hair is dripping and my feet are sore. I wave my sign and the loud cheering begins again. In the middle of all that indecipherable noise I hear “MOM, MOM, MOM” over and over again. It’s coming from the other side of the road. “What’s going on?” I think. I turn to look holding my sign way up high. It reads: Proud Mom! And there, among the hundreds of faces I think I see my son. But it’s so dark, I might be wrong. Hands go up waving at me, I see his boyfriend who is taller than him. I look again and then I’m sure. “That’s s my son!” I say to the air. “Yes, that’s him!” says Maria waving her hands and jumping up and down. And out of me comes a feeling of such profound love that makes me raise a hand and throw an exaggerated kiss to them, hoping they’ll see me. And they do, and send the kiss right back to me.

I keep on marching, knowing that the one who has the best part of my heart saw that part of me written on my sign. I’m bouncing now, happy to be tired and sweaty, so entirely pleased to be here. I look back at the rest of my friends marching with me and I see Peter, next to his wife, holding together their Proud Parent sign. I raise my sign, the crowd keeps cheering till the end of the line. I hug my sister and my friends. My beautiful, wonderful friends who honor their kids and all the gay people in this world. Without them, I would have never gotten to the place of love where I live today. I notice my cell phone hanging on my neck. I put my sign down and scrawl through the messages till I find my son’s. He texted: “Love you, mom.”

*Foto de Mercedes Mehling en Unsplash

Teresa Di Tore is a writer/translator who writes short stories and flash fiction in both, English and Spanish. She holds graduate degrees in Literature in both languages. She also volunteers to help parents of LGBTQ+ youth build relationships of love and acceptance with their children.

Teresa Di Tore is a writer/translator who writes short stories and flash fiction in both, English and Spanish. She holds graduate degrees in Literature in both languages. She also volunteers to help parents of LGBTQ+ youth build relationships of love and acceptance with their children.

An active member of Rose Mary Salum’s Writing Workshop, she is currently working on a collection of short stories.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

—¿Dónde está la carroza? —pregunto al mirar los rascacielos que nos rodean.

—Dice B-4, y eso está…ahí, a la izquierda—. Mi hermana María estudia un mapa arrugado. Al doblar la esquina vemos la carroza de nuestra organización. Me uní al grupo de Familias y Aliados hace tres años, cuando mi hijo salió del closet. A partir de entonces, participé cada año en el desfile de Orgullo Gay, pero esta es la primera vez que un miembro de mi familia me acompaña.

—¡Está hermosa! —dice Maria, contemplando la estructura de madera terciada situada sobre la camioneta pick up. El círculo pintado simula un arco iris radiante que resalta contra el paisaje de Houston. Asiento con un gesto, acordándome de las muchas horas que pasamos decorando la carroza. Muchos padres que recién se han enterado que sus hijos son gay están reunidos aquí. No saben todavía cómo manejar la situación, pero se han reunido hoy para mostrarles su amor y aceptación. Maria enlaza su brazo delgado y fuerte en el mío para demostrarme que está aquí presente, para apoyarme. Sus ojos color café se pasean de rostro en rostro, deseando conocer a los otros padres.

—¿Cuándo marchamos? —pregunta el hijo de José. Lleva puesta una camiseta negra y una calza sobre la cual se puso un tutú de colores brillantes.

—Somos el número cien —dice Sofia, revoloteando sus ojos azules y agitando un enorme abanico de plumas color arco iris.

—Ay, chicos, ¿no les encanta pasar la tarde con sus padres? —pregunta su madre, riendo y abrazándola. Hace ya tres años que forma parte del desfile, igual que yo. Solo que mi hijo no me acompaña. Al hablar con él más temprano, me dijo que estaría entre el público, viendo el desfile.

—Ahora me va a ver y va a comprender que lo entiendo —le dije a Maria, cruzando los brazos. —Digo, le estoy mostrando a toda la ciudad que lo amo y lo acepto—. Maria me regala una sonrisa triste. Estuvo presente cuando unos miembros de mi familia me dijeron que ser gay no estaba bien. Escuchó los reproches. Vio como trataban de hacerme sentir culpable por apoyar a mi hijo en algo inmoral.

La gente se arrima a la carroza. Algunos paseando sin prisa, otros sentados, visitando y pasando botellas de agua. La tardecita se va apagando, pero el calor sigue azotando y muchos hemos estado aquí ya varias horas.

—¡Nos olvidamos de los carteles! —dice José alarmado, agitando los brazos. —¿Será que alguien puede ir a buscarlos?

—No podemos irnos ahora. El desfile está por comenzar —dice Linda, apoyándose contra la camioneta. La ropa se me pega al cuerpo, pero el sol está empezando a acostarse y el pensar en la penumbra hace que todos suspiremos con alivio. José, Linda y los otros organizadores han trabajado el día entero para poder participar en este evento.

—Además, ¿quién quiere pasar frente a los grupos de odio que están en la entrada? —pregunta Linda, abriendo sus ojos exageradamente. —Hasta los padres más experimentados no soportan el asalto verbal de esos tipos.

Maria me da unas palmaditas en la espalda. ¿No será que nos pueden lastimar? Me había preguntado cuando pasamos por la entrada al llegar al parque. Yo me mordí los labios sin saber qué decirle.

—¡Aquí hay un pedazo de cartulina negra gruesa! —dice Linda. —Si consigo un cuchillo, puedo cortarlo en pedazos para que cada uno tenga un cartel. Tengo unos lápices de cera blanca y podemos escribir mensajes. Va a funcionar.

Miro al pedazo de cartulina que me dieron. —¿Qué voy a escribir? —le pregunto a Maria. Toco la superficie del papel con mis dedos largos, tratando de decidir cómo puedo expresar mis sentimientos. Me aterra pensar que alguien pueda lastimar a mi hijo. Trago fuerte y escribo rápidamente con letras grandes, apretando mis dedos hasta sentir dolor. Este es el mejor antídoto que me puedo imaginar. Quiero que mi hijo vea este cartel entre la muchedumbre. Quiero que vea mis palabras y que me vea a mí, su madre, declarando mi amor por él en forma pública. Exhalo mi dolor y miro a la gente que me rodea.

Peter se recuesta calladamente contra la camioneta, su cabello blanco aplastado por el calor de junio, cruzando los brazos, como protegiéndose. Observa a los demás escribir en sus carteles.

—¿Quieres escribir algo en tu cartel? —le pregunto, ofreciéndole mi lápiz de cera. Me tiemblan levemente los dedos. El niega con un gesto y desvía la mirada sin decir palabra. Peter ha estado asistiendo a las reuniones por menos de un año y no está listo. Lo entiendo porque mi primer año me sentí sobrepasada por el desfile, preocupada por la posibilidad de que algún conocido me viera y me juzgara. La esposa de Peter habla con él en voz baja. Lleva un cartel que dice “Papá Orgulloso” pero él le dice que no. Ella le da un beso tierno en la mejilla y se aleja, uniéndose a los otros padres del grupo.

—¡Vamos, vamos! —nos apura José y todos empezamos a caminar por las calles de Houston. Delante de la carroza, llevamos una pancarta con el logo de la organización. Yo camino detrás de ella, hacia el lado izquierdo. Elevo mi cartel por arriba de mis ojos para poder ver la muchedumbre que nos recibe.

—Te quiero mamá!

—Dale, dale, ¡dale!

La gente que nos rodea vitorea, y el tono sube, sube y después muere. Agito mi cartel un poco más, y todo comienza de nuevo. Trato de devolver las miradas de los jóvenes y de sonreírles. La gran mayoría son adultos—chicos jóvenes para mí, como lo es mi hijo. Sé que él está en algún lugar del gentío, viéndome a mí y a los otros padres que marchan para que nuestros hijos sepan que los amamos, y que a pesar de todos los miedos que nos acechan, los apoyamos.

Cientos de rostros jóvenes del público nos miran y me pregunto qué es lo que ven: una madre de edad madura, con un poco de sobrepeso, cabello corto y teñido, lentes de marco obscuro y una sonrisa enorme solo para ellos. ¿Puedo esconder mis miedos? Aun puedo escuchar las voces de mis parientes.

Mi tía diciendo, —No hay homosexuales en nuestra familia. No hay de esos.

—Es demasiado joven todavía. Está experimentando —mi primo explicaba. —Lo criaste bien, ya le va a pasar, vas a ver.

Yo solía fijarme en las personas gays de mi grupo de Amigos y Aliados y pensaba que mi hijo no era como ellos. Que nosotros no éramos como ellos. Ese sentido de otredad permaneció conmigo hasta que llegué a aceptar que mi hijo, que es tan parecido a mí—más que nadie lo será en mi vida—es gay. Sé que es difícil entender, comprender que hay diferencias grandes entre nosotros y los seres que amamos profundamente. Pero esta realidad me invadió el momento en que confesó que era gay. No pude negar, encontrar excusas, o dejar de ver por mucho tiempo cómo era la vida realmente para él. Yo era parte de esa vida, porque él es parte de la mía. Un padre empieza a ver, a comprender. Todos estos chicos, estas caras entre la gente, son tan hijos míos como lo son de sus madres. Somos todos lo mismo—iguales en nuestras necesidades, deseos y amor. Somos diferentes solo en la forma. Las caras pintadas, los cabellos teñidos brillantemente, las poses torpemente atrevidas, los disfraces risqué, y las insinuaciones sexuales desafiantes parecen decirnos, —¡Veme! Existo y necesito amor—. ¿Cómo puede una madre decir que no? La gente saca sus teléfonos celulares y me retratan. Me pregunto donde postearán esas fotos. ¿Será que mis amigos están entre el gentío? ¿Estarán viendo mi cartel? No voy a permitir que los jóvenes perciban en mi rostro el miedo que me invade. Parpadeo para aclarar la vista, y veo solamente a los chicos. Solo escucho sus voces.

Una cerca separa a los que marchamos de la muchedumbre que viene a vernos. Una jovencita se dobla sobre la valla y extiende los brazos lo más que puede, sus ojos fijos en los míos, ofreciéndome el collar más elaborado que tiene. Está hecho de perlas grandes de plástico blanco, con un colgante plateado en forma de corazón. Rompo fila con mis compañeros y me acerco a ella, bajando el cartel para que pueda colocar su ofrenda en mi cuello. —Te quiero, mami— murmura y yo le brindo la sonrisa más brillante que tengo, sabiendo muy dentro de mí que en algún lugar hay una madre a la que le está dando esta dedicatoria, deseándola, extrañándola terriblemente. Dejo que el collar descanse su peso de amor sobre mi pecho y vuelvo a mi lugar en el grupo, pensando en mi hijo.

Me doy cuenta que no sé dónde está, de qué lado de la calle se ha ubicado, o si siquiera puede verme. No escuché mi teléfono, que está bien resguardado en una bolsa que cuelga de mi cuello. Me perdí su mensaje, pienso, y empiezo a buscar entre el gentío. Agito mi cartel y los chicos empiezan con renovado vigor a llamarme mamá—a sus mamás, a todas las mamás que representamos en este desfile. Sonrío, y las manos se levantan pidiendo chocar los cinco. Quieren saludarme para honrarme por estar honrándolos a ellos con mi apoyo. Choco las manos jóvenes con todo el amor que tengo, pensando que en nuestra experiencia humana, todos somos un solo cuerpo.

No puedo ignorar los cientos de chicos parados a los lados de la calle, esperando que marchemos para celebrar el orgullo gay. Pienso en los teléfonos y me pregunto quiénes estarán viendo mi cara. Quién continuará siendo mi amiga, y quién va a hacerme daño con sus palabras. Mis brazos comienzan a sentir el peso del cartel, pero vuelo a elevarlo una vez más. Veo a un fotógrafo entrar al perímetro de los que marchamos con un trípode y una cámara de buen calibre. Me toma fotos, una y otra vez. Fotografía mi cara de madre sosteniendo el cartel. Trato de sonreír, ignorándolo y concentrándome en los chicos. ¿Es uno de los periódicos locales? murmuro sin dirigirme a nadie en particular. Empiezo a notar todas las cámaras que me tienen en la mira. La gente se entusiasma y saca los teléfonos. ¿Quién va a verme? ¿Y si algún amigo me reconoce? ¿Los que ya saben y los que no? ¿Qué dirán? ¿Será una sorpresa? ¿Me van a volver a hablar? ¿Volverán a invitarme a sus fiestas? ¿Me tendrán lástima y rezarán por mí? ¿Cómo voy a reaccionar a los comentarios agresivos? ¿Con suavidad o de mal humor, sin darles tregua? ¿Saldrá mi cara en los medios? ¿Se enterará la gente en el trabajo? ¿Y mis parientes? ¡Dios mío! ¿A los que no les conté todavía porque sospecho que van a ser despiadados? ¿Y los que son amables, pero me van a tener lástima en silencio? Siento que el sudor me corre en la espalda, y me repito que tengo que mantener la frente erguida, para mostrar lo que albergo en mi corazón sin importar razones. No te enloquezcas, me digo a mí misma y sonrío a la gente. Tómate ésta, camarógrafo, toma la foto de esta madre sonriente.

No puedo ver a mi hijo entre la gente y ya entramos a la recta final. Me esfuerzo en ver, quiero encontrar a mi hijo, pero me duelen los brazos y siento que me están saliendo ampollas en los dedos. Una vuelta más y llegamos al fin. Apuramos el paso. Levanto mi cabeza una vez más y camino más rápidamente. La gente se vuelve más ensordecedora. Mi cabello llora sudor, me duelen los pies. Agito mi cartel y el clamor se renueva. En medio de todo ese indescifrable ruido, escucho “¡mami, mami, mami!” una y otra vez. Y ahí, entre los cientos de rostros, creo ver a mi hijo. Pero está ya muy oscuro, puede que me equivoque. Veo brazos levantados, saludándome, y distingo a su novio, que es más alto que él. Vuelvo a mirar y la vista se me aclara.

—¡Ese es mi hijo! —le digo al aire.

—¡Si, es él! —dice Maria, agitando las manos y dando saltos.

Desde mi pecho surge un sentimiento de amor tan profundo que levanto mi mano y les envío un beso exagerado, esperando que me que hayan visto. Y me ven, y me mandan ese beso de vuelta.

Sigo marchando, sabiendo que el que tiene la mejor parte de mi corazón vio lo que escribí en mi cartel. Estoy saltando de emoción ahora, feliz de estar cansada y sudada, y completamente encantada de estar aquí. Miro hacia atrás, a mis compañeros de marcha, y veo que Peter está al lado de su esposa, sosteniendo el cartel de Familias Y Aliados. Abrazo a mi hermana y a mis amigos—mis maravillosos y bellos amigos que honran a sus hijos y a todas las personas gay de este mundo. Sin ellos, nunca hubiera podido llegar a este lugar de amor en el que vivo hoy. Por fin recuerdo el celular que cuelga de mi cuello. Bajo el cartel y reviso los mensajes hasta encontrar el de mi hijo.

—Mami, te quiero.