Puig Revival

John Pluecker

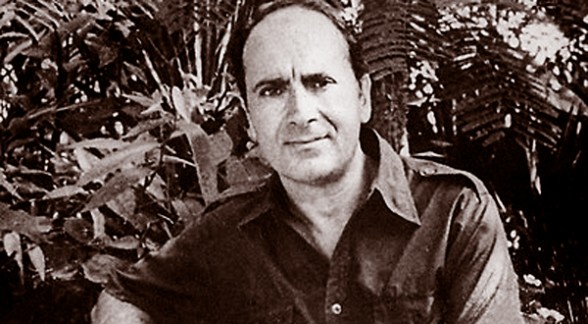

Manuel Puig,

Manuel Puig,

Heartbreak Tango,

Dalkey Archive Press, Illinois/London, 2010.

Juan Carlos is dead. As Heartbreak Tango begins, the male protagonist at the center of the novel is already absent, already beyond the frame of the story and yet still, unequivocally central. In death and in life, Juan is the spark that sets off wild fires of feminine passion. Multiple voices and perspectives explode on the first page–the lyrics from a tango and the small town newspaper obituary–as Puig creatively explores multiple perspectives on this story of one man and the women who loved him (an emphatically hollywoodense concept). Puig’s narration is constantly shifting, seemingly broken, and takes a panoply of forms: letters, tango lyrics, phone conversations, imagined thoughts, detailed play-by-play accounts of single days. He uses parody to recreate the social milieu of provincial Argentine life, vividly expressing the banal lives and petty conflicts and concerns of his characters. The book ends up being a kind of collage; however, dramatic events interspersed in the book–murder, disease, sex, partying, travel–make for an exciting ride.

In any review of Heartbreak Tango (and their have been many since its initial publication in 1969), one has a certain obligation to talk about the originality of the English version. Usually in book reviews, one or two lines are devoted to the fact of translation. The reviewer will throw in a pithy complement or an equally pointed barb about a supposed “error” of the translator that calls the “faithfulness” (i.e. servility) of the translator into question. Reading and reviewing Heartbreak Tango in English demands a different

kind of attention and an awareness of the subtle dance between author and translator, between the multiple versions of the texts in different languages.

The change in title from the Spanish Boquitas pintadas (Little Painted Mouths) gives us some clue about what has happened in the translation process. As Levine writes in her book on translation The Subversive Scribe: Translating Latin American Fiction, she was finishing up the book and translating lyrics from the popular song Maldito Tango when she stumbled upon the phrase “heartbreak tango” while trying to recreate rhythm and rhyme in the original. The phrase immediately struck her as a title, and, in consultation with Puig (who was a close friend before his death in 1990), made the final decision to go with this creative re-titling.

From the very cover of the book then, this is a translation that asks to be seen, commented and discussed. Having translated a number of the key authors of the Latin American Boom (Julio Cortázar, Adolfo Bioy Casares, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, among others), Suzanne Jill Levine is one of the preeminent translators of literature from Spanish alive today. Luckily for readers, Levine has written numerous texts about her process of translation and also about her relationships with the authors she has translated. She has even written a fascinating book, Manuel Puig and the Spider Woman, about the author, in which she combines memoir, criticism and biography to create a portrait of the author and her relation with him.

Levine talks about how she recreates the subversiveness of Puig’s text by making subversive decisions around language play, meaning, sound and rhythm. Rather than seeing herself as a faithful scribe, she delights in refashioning the original, retooling it and subverting it. One of the main examples of this is her complete “unfaithfulness” to the “original” verses of tango that start each episode of the book. For example, in Puig’s version, the book begins with the epigraph, “Era…para mí la vida entera…” by Alfredo Le Pera. Levine uses a completely different tango by H. Manzi, explaining in her own book that the original Spanish was so well-known to readers that it would instantly evoke a plethora of emotions that would have been lost on the English-language reader. Thus her decision to begin with “The shadows on the dance floor,/this tango brings sad memories to mind,/let us dance and think no more/ while my satin dress has a chance/to shine like a tear shines.” Levine diverges from a more “literal” translation in order to recreate the play and the emotional force of the original.

Heartbreak Tango is a gorgeous book, and Levine’s skillful reimaginings of Puig’s book allow the English-speaking reader to enter the complicated and rich world of Puig’s provincial Argentine towns.

Posted: April 22, 2012 at 1:38 am