Reading the Writing: A conversation between Tony Morrison and Claudia Brodsky (FRAGMENT)

Toni Morrison

Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison,talked to longtime friend and colleague Claudia Brodsky a professor of comparative literature at Princeton University. The conversation about politics and, especially, language took place at Cornell University

***

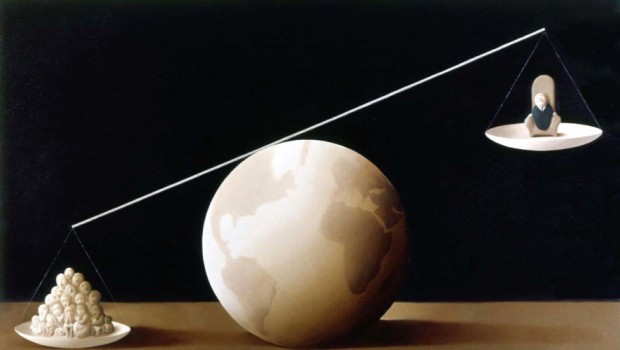

Claudia Brodsky. Recently you gave the Ingersoll Lecture at the Harvard Divinity School and the theme of the lectures series that you also addressed was simply the word “goodness”. The title of your lecture was specifically about goodness, altruism and the literary imagination. You, first suggested to me that that title would entail just the opposite argument from the one that you indeed in fact made. Rather than indicating the many ways and works in which the literary imagination has given voice to altruism, the selfless act undertaken from others, you instead described goodness in literature as personified very often as, this was your word, mute. You argued that what you called the “theatricality of evil” makes more compelling viewing “goodness in contemporary literature seems to be equated with weakness. Evil has a blockbuster audience. Goodness looks backstage.” You offered the following starling, indeed literally accurate observations about some of the most celebrated embodiments of goodness in modern English language fiction: “evil has vivid speech, goodness bites its tongue (…) Contemporary literature is not interested in goodness on a large or even limited scale. When it appears it is with a note of apology in its hand and has trouble speaking its name.” I want to hear if you want to comment on these observations yourself.

Toni Morrison. Let’s say that, before, I hadn’t explored as carefully as I did for the Ingersoll. But I was always a little bored by demonstrations of evil. They rely on the same things. I used to say it always has its top and the cape, and the tuxedo and the cane and has all the stuff glamour, and costume, but the goodness never has anything, because it doesn’t want anything, can’t use anything, it is just there. In the early literature, 18th and 19th Century, the Dickens kind of moved horrible life but there was this yearning stretch toward resolution. The good people survived and the bad people either didn’t or changed. That was true in many of them. Jane Austen, of course, was all about getting married and being married was good–if you got the right person. That was true of most of that literature. I think what happened was World War One, when goodness, and certainly after World War Two, when being a good person was trivial, almost silly. A character could only be understood to be good only if it was stupid, he was never clever, or sophisticated, or even well-educated. It was always vaguely stupid. Hemingway has a lot of those good stupid people. Except for himself, of course. He is always good.

I haven’t done the really important work which is to look at very recent literature to see if there is anything different about that. My sense is that there is not a difference. The good few books that I get and read, sometimes have extraordinary brilliant, beautiful language, but the trust and the effort in the language toward trying to explain something that is corrupt or lackey if not reaching the heights of evil, it looks around evil. That was opposed to interest the reader. It is not interesting to me. It is too easy. Goodness is really a truly art. You can’t seduce it. Hence, writing and trying to find a language for it, has been probably all that I have ever done in a novel.

Claudia Brodsky. Speaking from your most recent novel Home , at certain point of that lecture you did talk about your own work and cited the character Mss. Ethel, who says: “inside you is that free person, locate her and let her do some good in the world.” You also mentioned your first fiction The Bluest Eye and the misguided whish of the character to give quote “the gift of blue eyes to the little girl and psychotic need of them.” You went on to state: “In his letter to God, (the character) imagines himself doing the good that God refuses. Misunderstood as it is, it his wish has language. I myself cannot think of nothing more important one can give to goodness and no greater challenge to the literary imagination, than to make language work as language rather than as a beautiful picture or poor cousin of the ineffable, the transcendent and thus the necessarily mute.” What I’m really interested in asking, which is would you give us a comment on how you try in your novels to use narrative to give goodness language.

Toni Morrison. Yes,I thought I coined breeze, what I didn’t apparently I called it invisible ink. It was writing a novel in such a way that the reader gets taken in. The reader and I created it together and I did that by using this technique that I called invisible ink, where the meaning is in the structure. All the ending is always what I have to know before I start, because that is where it is going. That is where the meaning lies. I don’t always know the middle; I have to know how to get there. But I know that it is in the way that it is put together, what I withhold from the reader and what I dwell on at the same time. In that way I can employ wherever language as my disposal in order to summon in the reader disresponses display in something that really is moral. It is not cheap. It is not easy. It is hard one. It is very hard one. But it is like you are a girl, and you are black and you are young and that may be problematic for you. However, you are a person and deep down is this free person. That is the one you should be paying attention to. That is the one you need to use to do some good in the world. And that kind of simple clarity about what is valuable without painting some colors that are just set. These are hard one lessons spoken by people who have been there and are not crushed. I think one of the lines, which I use to hear a lot when I was little is that they were taking care of a woman in home, a woman who was down of her (…), and very sick and couldn’t help herself, and who was in labor who hated them, and always such she was above them and Oh lord! over them. But they take care of her which is in trouble and the author says the reason is that he at the end of their lives might say, or ask “What have you done?” And they had to answer that. They couldn’t say “I watched TV”. They did not want to be halting in their answer.

Claudia Brodsky. You are doing something for your reader. And that is very different from people simply making speeches. Takes a long time for simply get to the place where Miss Ethel can actually say that. First of all, she is almost dead.

Toni Morrison. Takes a long time for the crushed character who is very busy, looking for love or kindness or support, or “Am I OK?” “Is it true?” she is so desperate. And gets in a lot of trouble, so when she gets close to death and is literarily saved, when that happens. And by the way while she is ill the women say “Shut up, stop crying. Shut your mouth, (…)” They have no sympathy, just art, skill, and confidence. But they don’t want to hear wining, they don’t want to hear idiots, they are very tough, but they are also the people you can rely on completely and who would tell you those things that miss Ethel said.

Claudia Brodsky. Last Spring your work Desdemona was presented in Lincoln Center. The work is hard to categorize because it is not a play in any traditional sense nor spectacle. Would you please describe what “Desdemona” is and how it came about?

Toni Morrison. That was something I was extremely ultimately proud of and extremely excited about doing with Peter Sellers, who wanted to do something. It goes back a little bit. He was doing a course in Princeton, he was there for a month doing some drama with the students, and I was sitting outside in a bench eating lunch or something, and he said to me that he would never do “Othello.” And I said “why?” and he said “it is juts to thin, there is nothing there” And I said: “You are talking about the productions, which are kind of thin and predictable. Big black guy, little white girl. He kills her, whatever.” And I said: “but that is not it. First of all he is a moor, which means he is probably an Arab, second of all, she is not this little kiddy girl that he steals. A) She runs away from home. During that time either you went to the convent or get married. And she could have been in jail for eloping with him. That is a very daring thing to do. Secondly, she went to war with him, she sits in the edges of the battle and then she gets all involved in his business. So she was not this little, creepy, innocent little girl.” And I thought that when he was trying to kill her she probably thought he is strangling me. So anyway he didn’t Othello, a very interesting one in public theater. By the end of the time I had to agree to do what he asked me to do which was a play about Desdemona. This woman that I thought was much more interesting that what I have ever seen her performed on stage. And I said “why did she like this guy, anyway” (…) Othello comes, the captain of the army, and she likes him why?, well she says, and other people said, he began to tell her stories about his life, what he has experienced as a soldier, as a man, as a child, and they only mentioned one, but Shakespeare never describes those stories, that he told her, but he does said that she responded with tears. She was interested in the outside world. He wasn’t one of the local guys and she wanted out. And he provided this other world. But of course in the actual play Othello was never alone on stage. Ever, he was always with somebody. So I have this one requirement. I got very interested in Desdemona, but I said “Peter I cannot write this unless you let me take Iago out.” As long as he isn’t there, you know talks every minute, takes a whole conversation, nobody knows what to do with him, they lie to him or they try to please him. You know it’s like hopeless. That, for me, is part of what we were talking about earlier, which is connected not only to that gesture of removing Iago, but also what has been happening, more and more and more in my books, actually all of them, but to take away what I call the ‘white gaze’, whose I, whose language is controlling this. Well, in Othello it’s Iago. And when I began to write, the moment that I began to write, the publishing world of African Americans, was leaning heavily toward (I called it ‘witty books’ but there is a better word for that) and I published a million of them. And they would like the traditional African American novel where the oppressor is the white man or the white idea, you know the captain (…) you understood they were responding to defending themselves or aggressively attacking that idea of the white oppressor and I thought I can’t do that. What is the world like if he is not there? And the freedom, the open world that appears is stunning. And I noticed most African American women writers did the same thing (…) Those writers and the poets, because the poets were born more productive I think at that time than the novelists. But there were the free space open up by refusing to respond every minute to the (…), somebody else’s needs). So that flavor to great deal of what I was writing still does. But you’ll understand about Iago now.

Claudia Brodsky. You told me that Peter Sellers, the director, said that it was hard to talk about Desdemona for him and he had to call it “an event” rather than a play or a spectacle and that would have to do with the very openness that you are describing but still it is a really hard thing to pull off if you don’t have a drama, you don’t have a beginning, middle and end because you set out to write a spectacle in which everything that we witness is actually identical to what we hear, there are no actions per se. What we hear and also importantly what we read. So we witness the speaker’s minds and memories and work both alone and in dialog is that they give voice in what is after life. This play takes place in the afterlife.

Toni Morrison. Everybody is dead so they can say what is really on their mind, is timeless. And more importantly, they can learn, which they do. I mean, most.

Claudia Brodsky. Things happen but their verbal occurrences and it is quite remarkable and I have to say that special effects were not needed, people were captivated, I went to a couple of shows and people were captivated. I’m just going to let you…

Toni Morrison. (…) is a young woman from Mali and she sings and plays instruments. She is the first African Musician who said “most African music don’t have drums”. And I said “What?”. So she plays this other drum-less music. It is gorgeous and she is very famous, particularly in London, and so on. So she responded to what I wrote and she had songs for many of the characters. So what Peter did, which I think that was extraordinary, he has Desdemona, and she takes many of the other parts that are there, and he has Rokia, who is singing in the group of two women and two men. And then her lyrics and my text are huge on the stage. Not little things in the back of the opera house you know. You could actually read what she was saying. And particularly for me Rokia’s lyrics were the same way. Now understand this. Rokia is from Mali, her native tongue is Bambara. Bambara is not written, it is only spoken, so she takes an unwritten language, translates it into French, and then subsequently German, Italian and English. She didn’t do all those translations but somebody would take the French, because the play (…). (…) saw the whole sing the first time in France and then finally in English in New York. But I was thinking of, it’s not just that I couldn’t do it. I think she would have to write an unspoken language, I mean an unwritten language, a language that has no alphabet. So she has to write that down. And then she translates it into another language. And it is exquisite. I mean, it is truly exquisite, and we did a book called “Desdemona,” in which the text and the lyrics are there, in one book, and the plan was to do a film in Mali, but as you have read recently that is unlikely. But that was an extraordinary drama and exercise for me, under the guides of Peter, particularly, who was very stimulating intellectually.

Claudia Brodsky. I understand that you were going to counteract the notion of fitness now, the fitness of the play. And that you paid a lot of attention to Desdemona.

Toni Morrison. His Othello was thick. You know what’s the name? Hoffman? I told him I saw a lot of stuff that you did. And he says so I’m. He was Iago. Then we did Desdemona.

Claudia Brodsky. It must have been daring to write an event which is a postscript to a story of one of the most famous dramas in English and it wasn’t only a postscript because as you mentioned you were struck by the fact that what she fell in love with was his stories and stories are critical and you in fact created them.

Toni Morrison. I did all the stories that Shakespeare didn’t do.

Claudia Brodsky. Home, your most recent work is one of the most beautiful written of all your works and it has a particular powerful indication of natural centuries in the beauty, the beauty of the natural world, also the cultivated natural world. All those gardens in which nothing goes to waste I would like to ask you about how you got those centuries into view. It’s a very particular way in that novel. But first I wan’t to ask you about that period in American history in which you chose to situate it. The story of Home is a very Homeric story. A returning soldier warrior, it seems that he is from Ithaca. All your historical situated novels take place either in a time you memorialized in American literature, such as graciously, religiously and nationally ethnically, seventeenth century in America. I remember when Toni Morrison was first researching that book and very few people are aware of how absolutely rigorously Toni research is this. She said: “Claudia aren’t any decent books about seventeenth century in America? It is the most interesting time. Nothing got encoded yet and everything has different moneys and all of these different people and there are no books. Or you deal with a more publicized age, like the Jazz age, but from a point of view and about people in that age never written about before and as you pointed out to me: “And did you noticed that I never mentioned Jazz?”

Toni Morrison. The jazz age among us in literature is always Fitzgerald, people dancing and getting hip, you know. So it is a little exotic. And in literature they claimed it, like it was theirs. It is not yours, Fitzgerald.

Claudia Brodsky. I love Scott, I’m sorry.

Toni Morrison. Oh! I loved Scott too. I’m just taking a contra cultural thing over here. We never talked about the big time jazz musician. It is just all over a town. It is in the city.

Claudia Brodsky. Most beautiful descriptions of the city that I have actually ever read. But we have to leave that aside for now. Because I want to go back to Home. Why did you chose to write about the 1950s and the post-corean war in the U.S

Toni Morrison. It seemed to me that it was unwritten about. It was after the war that everybody was making money. When I heard these people before the first election of Barack Obama saying “we want to take our country back.” I think going to the 50s was “what” the back meant. I mean, some other things but that time in their minds is not what was going on. First of all there was a war that nobody even called a war, they called it a police action. You may noticed it is still going on. They have a militarized zone now. The soldiers at one side and the other. So there is this war thing. It was the high anti-comunism. People went to jail, lost their jobs, and it was also a time when doctors, scientists, were experimenting on helpless people, children, black people, etc.. We only got ahead of it in Vietnam because they experimented with LSD, on soldiers and then it was so horrible for a while. You might remember the experiment with the syphilis. They let have of the men get cured and then the other half they didn’t cure at all. Those things were things I wanted to create. He has been in a battle. A real one, where you kill people, and he comes back and it is another fight as a black man trying to get from area A to area B. And I never said he is black. My energy said something about that. And I said how do you know it is black? He said I just know. And I said “Oh!”. Now I have been with this editor forever and we read a lot and I think about what he says and what I might do and what I might not, but I know he is thinking commerce, you know. I had a little thing I stock in, when he goes to this preacher house and the preacher said you have been in an integrated army and you may think that North is different from the South, legal and costume are the same thing if the reader is interested. It is one moment where it comes very clear, not just that he can’t go in a restaurant or that he can’t go to a toilet. But all those says you just faked into the travel. He just is accommodating to it. All along, until he gets close to home.

Claudia Brodsky. You will admit that you are writing another novel right now.

Toni Morrison. I’m writing

Claudia Brodsky. You want to say any words about that?

Toni Morrison. No

Posted: September 23, 2013 at 1:12 am