Regarding Sighting of the Devil in the Café Nuevo Brasil

Sobre Avistamiento del diablo en el Café Nuevo Brasil

Tanya Huntington

I have been an aficionado of photography since childhood. I learned the basic rules of exposition and analog development from my father, who mounted a darkroom in the home where I was born. Even in my paintings or drawings, I almost invariably work with photographic images as preliminary sketches.

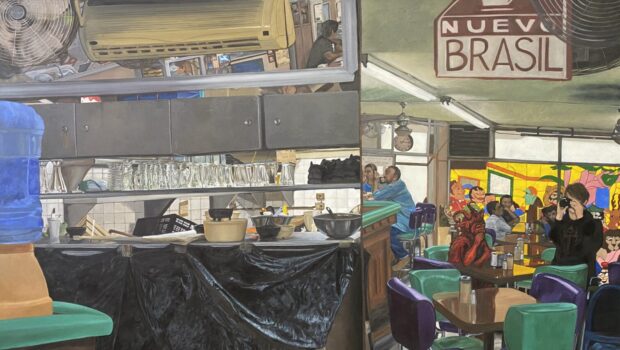

In this case, it seemed to me that painting was the only possible way to make use of an image that had failed as a photograph. The snapshot I took one afternoon in 2005 at the Café Nuevo Brasil was poor – poorly illuminated from the back, underexposed, slightly out of focus. And yet, it had something that seduced me, something that kept me from discarding it at the time.

Partly, it was the circumstances. The Café Nuevo Brasil was a classic hole-in-the-wall in Monterrey, a city I found myself visiting for the first time. To me, it was a very important occasion: one of my works had been selected for the FEMSA Biennial, a vote of confidence that meant a great deal professionally as a self-taught painter finding acceptance in the trade.

In part, I was attracted to the composition because it can be read as a profanation of Las Meninas, the renowned masterpiece in which Velázquez peers out from inside a portrait he is creating of the infanta Margarita. It was as if unwittingly, I had made an irreverent gesture of sorts to the great Spanish maestro that was at the same time a heartfelt tribute to all the greasy spoons of the world, that is to say, the popular restaurants that bear that name in reference to the abundance of grease found not only on the spoons, but on all the other surfaces as well. (Here, by the way, I experimented with oils until finding a combination between dark ochre, sienna, and moss green that is a fairly accurate approach to grease when tenuously applied as a upper layer).

I like compositions with mirrors. I find that when they are transformed into paintings inside other paintings, into successive trompe l’oeils, it makes us want to step through them, like Alice. They no longer perform the function of reflection, yet their possibility as wondrous thresholds is enhanced. In this case, I am fascinated by how they fragment and at the same time, unfold the interior space of the café. The stained glass window in the back moves to the foreground, and what’s off to the left is somehow relegated up above, where almost magically, a downward bird’s eye view is perceived. All of the horizontal planes are crooked. The gazes of the occupants of the painting look away or unexpectedly meet, generating nuances.

I also like chaotic, disorderly compositions with randomly scattered objects. The mustard container balanced in an unlikely fashion on top of a dirty frying pan, the marker inside a styrofoam glass, the black plastic curtain that precariously hangs from the counter, its weight barely sustained by a few bits of packing tape.

And of course, I like compositions that play with light sources. Here we see juxtaposed on both sides of the vertical dividing line created by the frame of the larger mirror a cold, fluorescent light from the kitchen and that white, blinding sunlight of northern Mexico that burns through everything found outside, on the other side of the door.

Finally, I like psychologically complex compositions. Hence, on this occasion, I chose not to grid the photographic image in order to facilitate its translation into the language of painting. There were many times I lamented my decision, given that it elevated the difficulty of execution significantly. But I have no regrets. I wished to avoid the coldness of pure photorrealism by uncorking the surreal impact of a fake snapshot: a candid scene intervened by the hyperbole of the imagination.

I mention this fiction in order to make a confession: it has taken me fifteen years to finish this painting. Which does not mean, however, that I have been constantly at work. I abandoned it for a very long time. In fact, I was on the verge of sanding down the entire canvas and using it for something else. This was because the central figure of the original painting was my husband, but he wouldn’t be for very much longer. After our marriage ended, the last thing I wanted was to complete a portrait of him. When my current partner interfered in a truly moving scene in order to prevent its destruction, standing between my upraised hand and my unfinished creation, I decided to turn to dreams as a creative instrument to resolve the dilemma of the main figure. The dream world suggested a way to solve the problem by transforming him into an allegoric figure, thus altering the original narrative of a family portrait. It seemed to me that if that figure were the devil, it would improve that narrative considerably. Moreover, it seemed to me a fitting gesture to a certain Mexicanness that I have grown to love after so many years of living here: one that swears, hand to God, that it has witnessed a variety of supernatural manifestations, from UFOs to the goat-sucker.

Not long ago, another fundamental interlocutor, my friend Arturo Delgado, pointed out to me that the result of that change was the transformation of my own figure within the painting, originally incidental, into the main figure, not unlike Velázquez in Las Meninas. Arturo showed me the ways in which the entire painting acts as a kind of unfolding self-portrait. Unlike Velázquez, my expression or countenance cannot be appreciated, because I am hidden behind the mask of my trusty Nikon. That mask amplifies one of my personae, my facet as an artist. But it is also the self-portrait of the devil’s lover or witch: my amorous or sexual self. And to one side, my son Dylan is found, a baby sleeping in his carriage – that is to say, a figure that highlights my joyful maternity. And of course, the entire result is ultimately the anti-mimetic representation of my subconscious, that is to say, of a dream I had about how to finish the painting you see before you today.

Tanya Huntington is the author of Martín Luis Guzmán: Entre el águila y la serpiente, A Dozen Sonnets for Different Lovers, and Return. She is Managing Editor of Literal. Her Twitter is @Tanya Huntington

Tanya Huntington is the author of Martín Luis Guzmán: Entre el águila y la serpiente, A Dozen Sonnets for Different Lovers, and Return. She is Managing Editor of Literal. Her Twitter is @Tanya Huntington

©LiteralPublishing

He sido muy aficionada a la fotografía desde la infancia. Aprendí las reglas básicas de la exposición y el revelado análogo de mi padre, que tenía un cuarto oscuro montado en la casa donde crecí. Incluso cuando ejerzo como pintora o dibujante, casi invariablemente trabajo con imágenes fotográficas como bocetos.

En este caso, me parecía que la pintura era la única manera de aprovechar una imagen que no funcionaba como fotografía. La imagen que tomé una tarde de 2005 en el Café Nuevo Brasil era demasiado mala – mal iluminada desde atrás, mal expuesta, un poco fuera de foco. Y sin embargo, tenía algo que me seducía, algo que me impidió descartarla en el instante.

En parte fue la coyuntura de ese momento. El Café Nuevo Brasil es un garito clásico en Monterrey, ciudad donde me encontraba de visita por primera vez. La ocasión era muy importante para mí –un cuadro mío había sido seleccionado para la Bienal FEMSA, un aval que significó bastante en términos profesionales y gremiales para una pintora autodidacta como yo.

En parte, me atraía la composición porque puede leerse como una profanación de Las meninas, el célebre cuadro en el cual Velázquez se asoma dentro de un retrato que realiza de la infanta Margarita. Era como si hubiera hecho sin querer una especie de guiño irreverente al gran maestro español que fuera a la vez un homenaje a todos los greasy spoons, es decir, los restaurantes populares que se llaman así en inglés como referencia a la abundancia de grasa que puede encontrarse no solo en las cucharas, sino en las demás superficies también. (Aquí, por cierto, experimenté con los óleos hasta encontrar una combinación entre ocre oscuro, siena y verde musgo que se asemeja bastante a la grasa cuando se aplica de manera tenue como capa superior.)

Me gustan las composiciones con espejos. Me parece que, al verlos convertidos en cuadros dentro de otros cuadros, en trompe l’oeil sucesivos, nos quedamos con las ganas de pasar a través de ellos, como Alicia. Ya no fungen como objetos reflejantes, pero la posibilidad de otro propósito, el de funcionar como umbrales hacia lo maravilloso, se realza. En este caso, me fascina cómo fragmentan y, a la vez, desdoblan el espacio al interior del café. La vitrina de atrás queda por delante, lo de la izquierda anda por allí arriba, donde se ve de manera casi mágica un plano picado hacia abajo. Los planos horizontales están todos chuecos. Las miradas de los ocupantes del cuadro se desvían, se cruzan, y así generan nuevos matices.

También me gustan las composiciones caóticas, desordenadas, con objetos revueltos. El bote de mostaza balanceada improbablemente encima de un sartén sucio, el plumón dentro de un vaso de unicel, la cortina de plástico negro que cuelga precariamente del mostrador, sostenido apenas por unas tiras de cinta canela.

Y desde luego, me gustan las composiciones que juegan con la fuente de luz. Aquí vemos empalmados en ambos lados de la línea vertical divisoria, creada por el marco del espejo más grande, la yuxtaposición de una luz fría, fluorescente de la cocina y aquel sol blanco, enceguecedor del norte de México que arrasa con todo lo que se encuentre al exterior, al otro lado de la puerta.

Por último, me gustan las composiciones psicológicamente complejas. Por eso, en esta ocasión, elegí no cuadricular la imagen fotográfica para facilitar su traducción al lenguaje de la pintura. Sin duda, hubo momentos en que lamenté esa decisión, dado que eleva la dificultad de la realización de manera significativa. Pero no me arrepiento. Quise evitar la frialdad del fotorrealismo puro a la hora de destapar el impacto surreal de una ficción: un encuentro fugaz con el diablo, registrado en una falsa instantánea; una escena de verité intervenida por la hipérbole de la imaginación.

Aprovecho mencionar esta ficción para hacer una confesión: he tardado quince años en terminar este cuadro. Lo cual no significa, sin embargo, que llevo tres lustros de trabajo constante. Lo abandoné durante mucho tiempo. De hecho, estuve a punto de lijar todo el lienzo y aprovecharlo para otra cosa. Sucede que originalmente, la figura central del cuadro era mi marido de aquel entonces, pero no lo iba a seguir siendo por mucho tiempo. Después del divorcio, lo que menos quería era terminar un retrato suyo. Cuando mi pareja actual me impidió destruir físicamente el cuadro en una escena verdaderamente conmovedora, interponiéndose entre mi mano destructora y mi creación incompleta, decidí recurrir al sueño como instrumento creativo para resolver el obstáculo de la figura central. El mundo onírico me sugirió la posibilidad de resolver el problema convirtiéndolo en una figura alegórica, alterando así la narrativa original de un retrato familiar. Me pareció que, si esa figura fuera el diablo, incluso la mejoraría mucho. Además, me pareció un bonito gesto a cierta mexicanidad que he llegado a amar después de tantos años de vivir aquí; me refiero a aquella que jura y perjura que ha atestiguado diversas manifestaciones sobrenaturales, desde un OVNI hasta el chupacabras.

Hace poco otro interlocutor fundamental, el galerista Arturo Delgado, me hizo ver que el resultado de ese cambio fue la transformación de mi propia figura dentro del cuadro, que originalmente era incidental, en la figura central, de modo parecido al de Velázquez en Las meninas. Arturo me señaló las maneras en que el cuadro entero actúa como una especie de autorretrato desdoblado. A diferencia de Velázquez, no puede apreciarse mi expresión o semblanza, porque estoy escondida detrás de la máscara de una cámara Nikon. Esa máscara amplifica una de mis personae, mi faceta como artista. Pero es también el autorretrato de la amante del diablo, o la bruja: mi “yo” amoroso o sexual. Y al lado se encuentra mi hijo Dylan, un bebé dormido en su carriola – es decir, una figura que realza mi maternidad gozosa. Y por supuesto, la obra entera es el retrato de mi subconsciente, es decir, de un sueño que tuve sobre cómo terminar la obra que ahora ven aquí.

Tanya Huntington is the author of Martín Luis Guzmán: Entre el águila y la serpiente, A Dozen Sonnets for Different Lovers, and Return. Her most recent book is Solastalgia (Almadía / UAA, 2018). She is Managing Editor of Literal. Her Twitter is @Tanya Huntington

Tanya Huntington is the author of Martín Luis Guzmán: Entre el águila y la serpiente, A Dozen Sonnets for Different Lovers, and Return. Her most recent book is Solastalgia (Almadía / UAA, 2018). She is Managing Editor of Literal. Her Twitter is @Tanya Huntington

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.