Regarding the Pain of Mexico

John Pluecker

A puff of smoke rising from the desert floor. Two boys kneeling, arms raised to display wooden blocks in their hands. A body lying prostrate before tall trees and verdant green vines. A fire racing through dried corn stalks. A kaleidoscope of white embossing with lacy brown edges forming the hint of a body.

All of these images are from an exhibition at Fotofest in Houston called Crónicas: Seven Contemporary Mexican Artists Confront the Drug War. Perhaps due to the large number of foreign photojournalists and artists who have traveled to Mexico in recent years to document and define the Drug War, this exhibit’s focus on more local interventions is particularly refreshing. As Susan Sontag wrote in her landmark essay “Regarding The Pain of Others,” “The memory of war…is mostly local.” This focus is apparent in all of the artists’ work as they grapple with their own sense of loss, their familial connections to the violence and the incursion of horror into the landscapes of their childhoods.

An important question is raised (if not answered) by the exhibit: What can art photography and video art do at this moment of great violence and repression? With the insistent repetition of brutal images of violence both inside and outside of Mexico, a certain lethargy has set in: a sense that what is happening is inevitable, and beyond that, many viewers now assume they know what is happening, that they are in touch with the “real.”

The most compelling work in Crónicas questions this assumption of knowability. It asks: how close can photo or video really bring us to the experience of violence? The most interesting work in the show examines, in the words of Ulrich Baer, “the striking gap between what we can see and what we can know.”

The work of Marcela Rico, for example: a series portraying her home state entitled Landscapes of Sinaloa depicts mysterious occurrences or situations–the explosion of gunpowder, the lighting of a small fire, rocks thrown into water, a lone tent–in the foreground of a larger, often imposing landscape. There are no dead bodies, no immediate depictions of violence; rather, the photos are mysterious and understated. The viewer is left wondering whether the events depicted are coincidences or whether they are, in fact, staged. As it happens, it is the latter; Rico intervenes in landscapes from her own childhood. The images do not show the horror of the Drug War. They attempt to show their own inability to make that horror known.

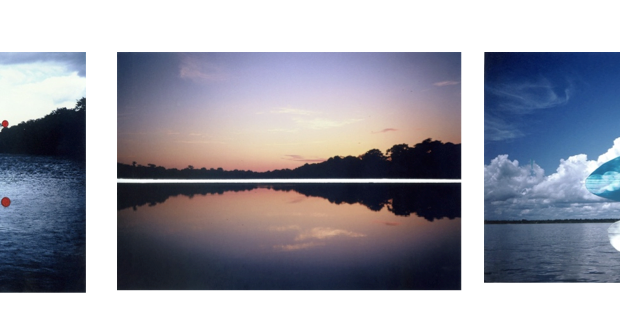

In Fernando Brito’s series, Your Steps Were Lost in The Landscape, we find a very different approach: the work of a Culiacán-based photojournalist with access to crime scenes, who takes photos far different from the typical nota roja fare. In all of the images, we find a body or bodies alone in beautiful and grandiose landscapes: in one, green verdure against a brilliant blue sky with puffy white clouds, a rotting corpse in the foreground. As in Rico’s work, landscapes loom large and yet, the inclusion of cadavers in the scenes changes them completely. While there are some parallels with Rico’s work–mystery, doubt, questions about staging versus reality–these are photographs of protest. The photos are intentionally unsettling, disturbing, raw and gruesome.

Moreover, I wonder about their political efficacy, particularly as they are presented in a series that does not name any of the individuals killed. As Susan Sontag also wrote, “A portrait that declines to name its subject becomes complicit: to grant only the famous their names demotes the rest to representative instances of their occupations, their ethnicities, their plights.” I wonder about these individuals: how we know less about them, even as they are seen. Their bodies have become allegories for the violence. At the same time, the photos do act as a clear denunciation of the quotidian nature of the violence. The bodies will soon be gone, the day will soon end; another will begin in the same landscape.

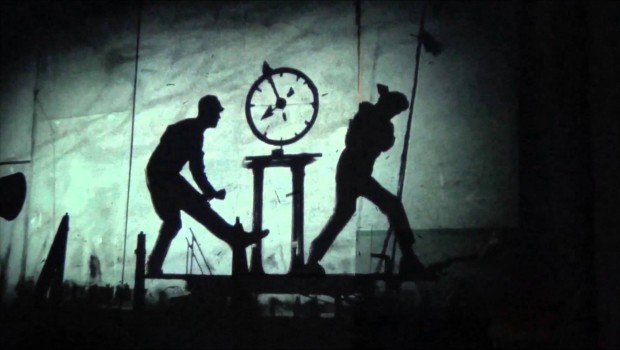

Another artist in the exhibit, oaxaquense Eduardo Aragón, makes videos that reenact familial and national scenes of violence and hierarchy with his younger male cousins and nephews as actors. For a viewer who does not know the context, these videos function as fables and become gestural metonymies in turn. Two young boys kneel, holding up wooden blocks that are shaped like the packages of marijuana typically seized by the military. In another, a man stands in the center of a sandy lot in a quarry as an SUV circles him, stirring up billowing clouds of sand and dust. In the end, the figure walks off, calmly, as if nothing had happened. There is an odd sense of tranquility in much of the work. As with Rico and Brito’s photos, there is a sense of mystery, of unanswered questions, a grasping towards a hidden narrative. What we see only highlights our lack of knowledge.

Finally, printmaker Miguel Aragón (also from Juárez but now residing in the U.S.) integrates photo with printmaking and uses compelling physical approaches to his subject matter that integrate form with content. For example, in Aragón’s White Juárez series, he uses a laser cutter to create cardboard templates that he then uses to make prints without ink. The burned cardboard leaves soot in intricate patterns at the lacy edges of the raised paper surfaces. In In the Vacant Lot, the image of the body practically disappears into the surrounding foliage: the array of intricate detailing created by the embossing process. Images like this one where bodies disappear present a damning reflection on the lack of visibility of the actual victims of the violence.

Especially in the context of an art exhibition in the United States, these photographs about the Drug War in Mexico have the potential to stir various conflicting responses: confusion, sadness, compassion, disgust, anger, an urge to make changes, or simply an apathetic awareness that horrible things happen. However, as Elaine Scarry has written, “When one suddenly finds oneself in the midst of a complicated political situation, it is hard not only to assess the ‘rightness’ and ‘wrongness’ of what is taking place but even to perform the much more elementary task of identifying, descriptively, what it is that is taking place.”

The best work from the exhibit compels viewers to do a double-take, to ask themselves what is really going on. In so doing, the artists have thrown into question photography’s assumed ability to act as an unmediated lens of the real. These artists resist the urge to supply the world with facile explanations or easy answers. They don’t let the viewer off the hook easily. Instead, the images turn back and ask the viewer: what do you really want to see of war? And why do you want to see it?

Image by Marcela Rico

Posted: April 28, 2013 at 3:50 am