Sex in Cinema

So Mayer

Becoming Visible

“What do you think of sex in cinema?” Well, it’s one way to close out the 2018 London Korean Film Festival. I’ve introduced, chaired Q&As for and been on panels at dozens of film screenings this year, and know that facing abrupt, tangential and even downright intrusive questions is an occupational hazard, both during the event and after. In the era of social media, there appears to be a new unspoken social contract that being in a public forum, however minor and however briefly, means that no holds are barred, as if any peeking above the parapet or taking to any platform immediately announces your consent to a non-stop, all-in #AMA.

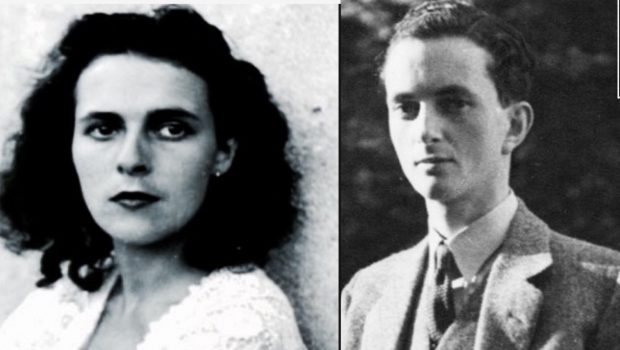

Perhaps if the question had come at me after the first LKFF event I participated in, a London premiere for Hit the Night, I’d have been less surprised. No doubt filmmaker Jeong Ga-young, in discussion with me after the screening of her second feature film, would have had an answer as smart, funny, and self-assured as her film. She certainly did for all the other questions from the audience, including a room-silencing question that doubled down on its sexism with some racism. But the question above came up after the closing night screening, The Return, which is a moving, metaphysical docu-drama about transnational Korean adoptees by Malene Choi. Lead actor Karoline Sofie Lee, herself a Danish-Korean adoptee like the director and her co-star Thomas Hwan, sailed gracefully through a challenging Q&A as she amplified the film’s delicacy and nuance, and was surrounded after the film by viewers wanting to share their experiences of adoption. Meanwhile, I got hit with: “What do you think of sex in cinema?”

It was a strange question to ask given the film that The Return features nothing more explicit than a long and complicated hug between Karoline and Thomas, who are both in Seoul looking for information about their birth parents, and staying at a church-run guesthouse for adoptees called Koroot. But of course in a narrative about adoption, there’s an implied story about sex and sexuality – not between Karoline and Thomas, but between their respective biological parents. At the turning point of the film, Thomas meets his biological mother (played by Seong In-Ja) and hears her story, which is one of unprotected teenage sex and social shame in a country where abortion is still illegal and contraception hard to access, feminist protests against which lack are ongoing. It’s implicit rather than stated, but it’s clear from Thomas’ mother’s spine-chilling monologue that transnational adoption arose out of the social stigma of the double sexual standard, which tends to disproportionately affect poorer women.

That’s both the story of sex in mainstream cinema – subject to the double standard – and a story whose detailed implications are perhaps not as familiar from mainstream cinema as they should be. That was a result of the Hollywood Hays Code which, from 1930 to 1968, precluded references to sex before or outside marriage, contraception, and abortion and thus put an end to proto-feminist filmmaking. Take Dorothy Arzner’s Working Girls (1931), from a screenplay by Zoë Akins, in which Mae (Dorothy Hall) has sex before marriage and doesn’t die, get abandoned or get institutionalised. Arzner’s radical vision was shaped by the 1920s, when contraception was starting to be accessible, if only by mail-order; when actors – if not their characters – boasted lovers, sometimes bisexually; and jazz-age fiction and theatre (like jazz songs) were addressing sexuality in witty, knowing ways.

The development of the visual, gestural, and choreographic language of sexuality in mainstream narrative cinema, however, was arrested by censorship nearly a century ago, and to this date, mainstream sex scenes (albeit watched over by the new intimacy consultants) remain framed by the prudish concerns of the Hays Code, as well as embedded in heteronormativity and racism. As Viola Davis recently told the BBC about the opening scene of Widows (Steve McQueen, 2018):

The film begins with me in bed with Liam Neeson, and we’re kissing, and it’s a sexualised kiss. Here I am, I’m dark, I’m 53, I’m in my natural hair… and I’m with Liam Neeson. I’m with what America would consider to be a “hunk.” He’s not my slave owner. I’m not a prostitute. It’s not trying to make any social or political statements. We’re simply a couple in love. And what struck me in the narrative is that I’d never seen it before. And you’re not gonna see it this year, you’re not going to see it next year, you’re not going to see it the year after that.

It’s a rare instance of sexuality in mainstream cinema being something other than the gratification of a very narrow range of white male heteronormative fantasies, fantasies that often uphold the double standard, waive consent, and may endorse violence. Rachel Bloom, creator of sex-positive network TV show Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, recently tweeted about the unrealistic conventions – well, clichés – of mainstream narrative depictions of heterosex, particularly that women orgasm from penetration. Or rather, given that MPAA and other national ratings mean that penetration cannot be shown, that women appear to orgasm merely from the excitement of being in the presence of a cisgendered man.

For the most part, therefore, sex on screen is awful: a cringemaking, sheetily-choreographed adherence to norms of embodiment and indicators of social status, encoded as a ‘fantasy’ of romantic heroism. So why, given that, did I say I want to see more sex on screen – a response that prompted my questioner to hightail it, horrified? By which I didn’t mean (just) pornography, although I am a Shine Louise Houston fan and think it’s crucial and exciting that she’s included in the Sisters in the Life project. Her presence there is indicative of the fact that queer filmmakers and filmmakers of colour have often worked in modes outside the mainstream: while that may mean documentary or community filmmaking or experimental, it might also mean porn, as Houston makes it, as an expression of all three. Rather than presenting the mainstream codes of sex on screen, Houston’s films document queer women’s sexual expressions and fantasies as community-building, and in doing so, she has developed an experimental film language to navigate making consensual queer porn.

As Barbara Hammer subtitles her autobiography Hammer!, queer mediamakers in particular are often “making movies out of sex and life.” Sex and sexuality are that which heteronormative patriarchy uses to oppress those who don’t adhere to its norms, and that is especially true for those from non-European cultures where colonisation and missionisation enforced the kinds of social shame seen in The Return. Films such as Moonlight (Barry Jenkins, 2016) have just begun to address the colonising of non-white sexualities and gender expression within the mainstream, just as The Return uses the lingering, achingly intense embrace between its protagonists to suggest the complexity of pushing back against an inheritance of sexual shame amid the emotions of first encounters with your birth parents and birth culture.

We need more films like these, and like Campbell X’s VISIBLE (2018). X, the director of Independent Spirit Award-winning East London queer romcom Stud Life (2012), has form in realising sexuality on screen as community-building, consensual, decolonial, and also – and because of that – really hot. VISIBLE is a documentary that looks to redress the absence of queer, trans and intersex people of colour (QTIPoC) from British cultural and social histories, and of that British history from understandings that tend to focus on North American QTIPoC figures and movements. And at the heart of VISIBLE is a glimmering sequence of archival images and imaginings that insist, deliciously, that this history will not be sanitised and desexualised. It’s an eruptive cinematic moment in the spirit of Isaac Julien’s legendary (and hard to see) short film The Attendant (1983), which brought queer BDSM into the museum, and specifically Wilberforce House in Hull, one of the few museums of slavery in the UK.

VISIBLE is part of a social and cultural movement in the UK and transnationally to decolonise, not least by undoing the damaging myths of binary and essentialised gender and heteronormative and churched sexual relations, and their colonial use to attempt to deny and destroy cultures and societies. But it’s also a rare example of this resurgence finding its way into the expensive industrial medium of cinema, whose gatekeepers (like the person who asked me the question) still seem to hold the Hays Code close to their cold, dead hearts. We need more films that offer up a glorious challenge to the idea that sex in cinema is a way of blatantly signalling a character’s feelings at best, and often just another choreography of white male dominance (including behind the camera) at worst. Making sex, sexuality and their social and historical context visible: my hope for 2019.

So Mayer is the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema, The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism and Documentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

So Mayer is the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema, The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism and Documentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

Posted: January 30, 2019 at 11:34 pm