Simone

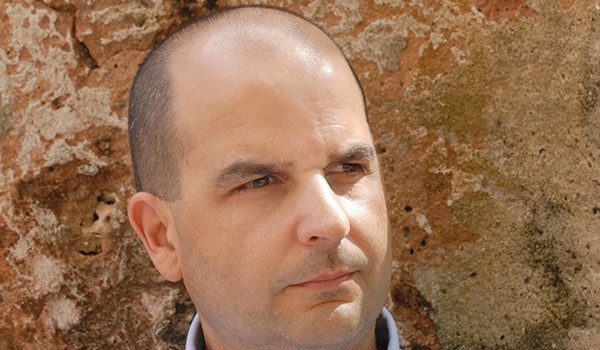

Eduardo Lalo

After a few moves, I’d lost three pieces, and when I hesitated for a long time over whether to move a bishop, I heard her say,

—Every four seconds a child dies of hunger somewhere on the planet.

She must have seen that I didn’t understand because she added impatiently,

—At least two hundred have died by now.

That was Li. She seemed to know all the statistics in the world, the illuminating ones and the trivial ones alike. She knew the per capita income of Togo, the inflation rate in Peru, how many more years the tropical forests of the world had left at the current rate of clear-cutting, the number of automobiles in Puerto Rico, and as a point of comparison, the number in Sudan; she knew how many pints of blood the human body contained and the weight of dolphins’ brains, how many spermatozoa there were in an ejaculation, and how many kilos of salmon a bear ate during an Alaskan spring.

When she referenced a set of numbers at inappropriate times, it was like she was parodying the way we cite facts, questioning through exaggeration the numerical reality of the world. I observed her strong hands; the slight plumpness of her body that she tried to hide with loose clothes; her round face with full, pale cheeks; her black, listless hair parted in the middle and frequently tied back in pigtails. Taken all together, I realized, she would lead me to surprises. Li, a Chinese woman living on a Caribbean island who approached the works of novelists, thinkers, and artists as if they were musical scores to be interpreted, took every aspect of life like a young girl who’d seen it all.

I watched as she drank two café con leches, ate three different kinds of pastry, let me win our very quick, second chess game.

I remembered the passages she had underlined in the Simone Weil biography. Almost all of them established the distance at which the thinker had lived from her contemporaries, even if she had been so committed to those in need that she had attempted to repair that separation. More than one heartache lay behind her dedication. I’d seen enough of Li, though we’d never met in person before this night, that I could imagine her reasons for choosing her pseudonym.

—Why Simone Weil? I asked.

—I like that name. She used to study on her knees.

—On her knees?

—Yes, she studied on her knees, spent hours reading on her knees. She was a philosopher who had been humbled. She was half crazy but totally lucid. What I respect most about her work is that she understood that you don’t stop being humbled after you learn that’s who you are. She never claimed to escape that reality.

—Why me? I asked. Where did you see me, how did you find out about me, why all this effort, this game that you took so seriously?

—I met you through your books, and then I saw you at the university. I’m the only Chinese woman in comparative literature.

—You know you’re not answering the question.

—Of course.

—So?

—It’s impossible, or rather it would be complicated, to give you an answer tonight. The important thing is that we’ve gotten this far, and I really thank you for coming. Aside from that, you can use this opportunity to improve your chess game. Starbucks was closing, and Li went to the bathroom. A short time later the server brought me a note. “They’re coming to pick me up. If you’d like, you can stop by the restaurant. I get off at 10:30. Don’t obsess about the whys. Over the long run, I know that nothing can stay hidden. Ciao. Li”

As the weeks went by, I would realize the extent to which Li lived in a practically closed world, still untouched by the consumer society or basic liberties, where high status meant having a tiny room of your own to sleep in, with space in a corner for storing your clothes and, in Li’s case, for keeping a few piles of books and papers.

She worked six days a week in the restaurant and had done so from the age of eleven. She was a distant relative of the family that owned a half dozen Chinese food places in San Juan and in a few towns on the island. She had been born in 1969 in a small village on the outskirts of Beijing that was, according to Li, an unhealthy flatland, cold and damp, full during that era of officials forced by the Cultural Revolution to be “reeducated” through agricultural labor. She held onto few memories: the muddy pools that filled the streets, the endless rice fields, the taste of boiled potatoes, her grandmother’s lap, a couple of songs. Her family had to split up because her father, a math teacher, was accused of coming from a family of “intellectuals.” Given the abject human relationships imposed by the Cultural Revolution, this meant that Li’s mother could not maintain any ties to her husband, and she was forced to denounce him and repudiate him formally and publicly. Her father was sent to villages farther and farther away from the capital until he must have succumbed to the cold, the hunger, the sentence he had been given for knowing how to read and write, for owning Soviet geometry textbooks and an old prerevolutionary translation of Madame Bovary, for having a bourgeois taste for jazz. After countless close calls, her mother managed to reach Hong Kong with Li, and from there, of all the places in the world, they traveled to Puerto Rico thanks to the efforts of some distant family members. She was six when she arrived.

Early on she didn’t even live in San Juan; she shared an apart- ment with other family members on the second story built with unfinished concrete blocks above the Gran Muralla restaurant in Arecibo. From there, she’d moved to one on Avenida Fernández Juncos in Santurce. At school and on the street, she was always la china. For years, hardly anyone outside the restaurant called her by her name. Nobody was interested or could understand her history. The distance, size, and complexity of China made it unfathomably abstract.

She lived with cousins, aunts, uncles, and “relatives” of un- known kinship, in grotesque overcrowding. She was the only one who learned how to speak and read Spanish well, and this was probably why they let her graduate from a public school in Santurce. There she was one of the few students who got to the last pages of books and the only one who spent all her free time in the modest library.

After a long struggle, she managed to persuade her family and, at the age of twenty, she enrolled in the Universidad de Puerto Rico. She somehow found a way to put herself through college, and in particular to pay her full tuition, by working at the restaurant. She submitted to unwritten rules: the restaurant owner’s family had gotten her out of China, and it was her obligation to work for him in exchange for a roof over her head and laughable wages over an indefinite period that might last her whole life. Now, Li said, she was working to purchase her freedom in the family’s best restaurant, the one where you earned the most. Apart from her fellow students, who always kept their distance from her, I was the first non-Chinese man she had taken the initiative to get to know.

After giving me this sparse outline of her life, she said I could now understand why she preferred books to men and why, of all possible men, she had felt curious about a man who was a writer.

—Hardly anybody reads me, I said.

—Hardly anybody sees me, Li replied, or if they see me, they see a Chinese woman. Not many can see anything more.

—We’re alike. Why don’t you write?

—Do you read Chinese?

—You could write in Spanish, you speak it so well.

—I couldn’t do it in Chinese either. I never learned to write in Chinese, and I speak it like an immigrant. I can say, “You rike big prate flied lice.” My problem isn’t the language but the impossibility everyone else has of imagining me. Is it possible to write when no one shares your identity, when the vast majority of people can’t even imagine you?

—Do you think it’s so different for me? Besides, I added, that can be a good literary space. Isn’t a writer already a species apart?

—But being a Chinese woman in Puerto Rico is much more extreme.

—That’s natural. It’s hard anywhere to be a writer, even harder to get yourself read with a minimum of attention. Your position here is extreme, but that’s not enough to convince me. There’s something else.

—You can’t write if you have no words, said Li. If the words have always belonged to others. That’s why I prefer to read, to take the words that others write and transform them. That’s what I’m familiar with. That’s what I’ve always done.

—Then it’s what you should do, I said.

—It’s what I did with you.

I’d go see her at ten, when few diners remained in the restaurant and the employees wrapping up their shifts were straightening the tables and leaving the place ready for the next day. We rarely talked in her room. I’d invite her to a pizza place or a restaurant with Puerto Rican cuisine; either way, she loved the food. I came to see from the way she ate that Li had never taken food for granted. She chewed conscientiously, with perfect concentration, and didn’t leave a bite on her plate.

—Do you remember China, from when you were a child?

—Of course. But my memory has more gaps than anything. I don’t remember the past so much as feel it. Maybe that’s hard to see, but for me, it’s been normal. The past is something I find in silence. I’ve spent my life surrounded by noise, first in China with my family and the neighbors who practically lived with us, then in Hong Kong among the refugees, later on in Arecibo, in San Juan, in the noisy racket of the kitchens and the traffic of the avenues reaching the rooms where I’ve lived day and night, but my life has been coming and going, if I can put it like this, to silence.

—Does it bother you?

—I’ve had no other option. This is the only world I’ve been in. The world of Li Chao; the planet whose total population is made up only of me: one Chinese woman among more than a billion Chinese, one Chinese woman on an island where there are no Chinese except in restaurants, one Chinese woman who doodles and reads.

After midnight, I’d drop her off in front of the restaurant. She lived in the rooftop apartment. Then I’d go home, which wasn’t far. It was the coolest part of the day and I felt fine. Things

were better since Li was there.

I wouldn’t go straight to sleep. I’d put on music. Drink a glass of juice. Look for a notebook and write. For the first time in a long while I was content.

I’d get into bed and contemplate the shadows the trees made on the ceiling. I didn’t even know whether I wanted to sleep with Li, whether there was any need.

A couple of times I tried to get her out of her regular environment. She had been living in this country for more than twenty years and had hardly been outside of San Juan and Arecibo, the city on the north coast where she’d spent part of her childhood. It was difficult to believe, but she’d hardly ever gone swimming in the sea.

I took advantage of some of her Thursdays off to take her to Salinas or Cabo Rojo and eat fresh fish or to introduce her to a beach or a forest. I met with little success, as there were few people more urban than Li. For her, nature was to be found in a can of bamboo shoots or a large sack of rice. All the rest was a bad memory or something she had no intention of experiencing. She therefore preferred to go on short excursions where, instead of doing anything I might suggest, we’d wander around the city on foot or by car till very late, on more than one occasion getting to watch the sunrise from the sea shore in a park in El Condado.

We’d talk for hours, drinking a thermos of tea from the same cup, spinning the stories of our lives and of the books we’d read. For someone like her, culture wasn’t about privileges or entertainment. Instead, as she stole time from her sleep and work and put up with the incomprehension of those around her, she was using culture as a weapon for survival.

As the sun was rising, I’d rush her back to the restaurant, before the city’s avenues and express lanes became clogged with traffic. Li would sleep a few hours, work her shift, read in the afternoon if there were no diners in the restaurant, and wait for me to arrive every night.

During the day, I’d recall how she would speak with her face turned aside, eyes fixed on the horizon. I’d remember the stories she told in the nearly flawless Spanish that had earned her a pro- motion to waitress in the clan’s best restaurant and permitted her the rebellious act of going to college. Though an enormous gulf separated our origins, in the intonations of her voice and the stories behind them, I heard the deep rumbling of the city that had befallen us like a sickness.

On one occasion, Li had to sub for a fellow worker on a Thursday, so she got a rare Friday off.

—I’d like to show you something I’ve been working on, she told me over the phone. Take me out somewhere. Indoors, please.

—You want to have pizza, I suggested, knowing how much she liked it.

Friday night had just begun and a river of cars was slowly flowing out to the suburbs and shopping centers along Avenida Muñoz Rivera. When I got to the sushi bar, Li had been waiting on the corner for a while. She had her hair in a ponytail and wore a black skirt and a pale, vaguely Asian blouse. She carried her usual cloth bag on her shoulder.

I brought some bad news. I’d learned that afternoon that the editors of an anthology had decided to cut me from the project. I should have been brave enough to admit that there had always been a chance of my being cut, so I had nothing to gain from acting moody or listless. Still, I was irritated when they used the clumsy excuse of my books’ publication dates to justify excluding me. More likely they hadn’t even read my stuff. Once more, they’d rely on personal whims and the old boy’s network to bestow recognition. It wasn’t much of a consolation for me that Máximo Noreña was also spurned. In his case, the editors’ reasons had been even more awkward and baseless.

Creeping toward El Condado, trapped in traffic among hun- dreds of other cars, I found it hard to react to the enthusiasm with which Li was weaving her sentences. The bad news kept spinning in my mind and I couldn’t turn it off.

Streets and avenues were gridlocked, and there was no way to reach the highway entrance ramps. It took us more than half an hour to reach Santurce, and it was uncertain whether we could continue to El Condado on Avenida de Diego because of a concert being held in Bellas Artes. I remembered a pizzeria nearby where I’d eaten with Diego. A lucha libre star I’d seen on TV as a child used to hang out there. His forehead, much darker than the rest of his face, was covered by a scar that looked like tree bark.

I parked in front of an exquisite house, probably built in the 1930s, that had been abandoned for years and was up for sale. We walked one block to the pizzeria, full of families and couples, and sat down in the only free booth.

I tried using the noise level inside the place as a cover for my silence. I hardly ate, letting Li devour the anchovy pizza. To talk about something, trying to disguise my reticence, I told her about the wrestler who used to be a regular at the restaurant. I was sur- prised to learn she knew perfectly well who I was talking about. For the Chinese who barely understood Spanish (also true of her at the time), The Stars of Lucha Libre was one of the few programs they could follow. The twenty inhabitants of the rooftop apart- ment would sit down in front of the TV set every Saturday, with a passion comparable only to what they felt watching martial arts films from Hong Kong.

Li knew what was going on with me since I had told her about it on the slow drive to the restaurant. I supposed my bad mood would dry up like a puddle, leaving a dry, brittle scab like the wrestler’s forehead. That’s how I was treating Li’s first Friday off, overwhelmed by negativity, no desire to do anything.

—Here, she said. It’s for you.

She had pulled from her bag a roll of paper no more than eight inches wide. I took it and started unrolling it. I soon realized it would be almost impossible to finish the job there since it was more than six feet long.

—I used up three ballpoint pens making it, she said when she saw in my face that my mood had lifted.

From top to bottom, except for the narrow natural margins, Li had covered the long sheet in one labyrinthine line, creating a black mass that looked alive, as if it might be vibrating a millimeter above the surface. It was an epic feat of determination and patience, both the tireless cycling of a machine and the unique mark of a hand.

—Do you like it? she asked.

—It’s the best thing I’ve seen in a long time. I wasn’t lying. Her drawing stood out against the works of many artists that were nothing but parodies of international fashions.

—But it’s ridiculous, she said. Three ballpoint pens’ worth of ink, on two meters of the paper that comes on rolls for the restrooms in the restaurant, drawn by a Chinese woman with no title who works like a dog in a country where chinitos aren’t supposed to be good for anything but selling egg drop soup and egg rolls. In other words, the work of a nobody. I suppose I ought to do like you, spoil the night and cry in a corner.

—But it’s so good, I said. You should use better paper. And not ballpoints.

—That wouldn’t change anything. It would even reduce its impact. You don’t realize, you’re looking at an anonymous work. Li Chao doesn’t exist. She’s just one Chinese woman from among 1,300,000,000 Chinese, not counting those who’ve emigrated and are living overseas, and from among 4,000,000 Puerto Ricans who don’t even look at themselves. A lesbian who took to using the words of others to pursue a writer whose failure is eating away at him today.

She rarely talked about herself. Her efforts to contact me had been a very effective way to avoid confessions. She armored herself in other people’s words and, at the same time, used them to express herself elliptically. Her lesbianism didn’t come as a sur- prise, but her decision to tell me about it did. She was trying to draw me out of my shell and force me to see her. She didn’t want our relationship to be a failure. Neither did I. I wanted something from her, and despite her confession, I felt I wasn’t far away.

I took her hand, and we gazed eye to eye until we both looked down at the same moment. A man and a woman are transformed when they look straight at each other and for the first time the silence doesn’t weigh on them. After that they’d be fooling themselves if they pretended nothing was going to happen. A new story begins then, and there’s no backing away.

I asked for the check.

—I want to show you something now, I said.

The avenues had freed up. I went down Ponce de León to the bridge that connected with the islet of San Juan, turned around, and drove to San Patricio. We felt a peace and calm in the confines of the car that we hadn’t shared till then.

In front of the shopping center where we had first met, I made a U-turn and took Avenida Kennedy toward San Juan. On a Friday at that hour, in this area lined by dealerships where they sold every model of car on the country’s roads, there wasn’t a soul to be seen. As I held the gear shift, Li rested her hand on mine and brought her head close until it rested on my shoulder. I turned toward her and, for a second, held the warmth of her lips on mine.

—Now look at the lights on the bridge, I said.

We looked ahead at the streetlight poles. Constitution Bridge was a kilometer and a half away. Crossing it, we would have Hato Rey on our right and on our left San Juan Bay. I was going exactly fifty miles an hour. I had it all calculated: I had done it countless times. The streetlight poles created the illusion of rising up until, for a few seconds, with the magical precision of optical illusions they formed two gigantic question marks on either side of the ave- nue. Realizing what she saw, Li squeezed my hand, and I heard her speak so close that her voice seemed to be coming from inside me.

—I’m sorry. I must have filled your head with questions. If it’s any consolation to you, you don’t know how many questions you’ve raised for me.

—Tonight is full of the hardest questions.

—I know, and perhaps they have no answers. A little later, we were back in Santurce and once again were driving along sections of Avenida Ponce de León. The city seemed to constrict us with its limited circuits. It wasn’t worth repeating the same trip. Undecided and fearful, I asked:

—What do you want to do?

I felt her search for the answer, hold it in her mind for a second, and dare to say it.

—Take me to your place. All I ask you is not to penetrate me.

I had never made love under such a severe restriction, but as in so many other things, Li led me through unexplored territory. Her full breasts, the graceful curve of her belly, the skin of her shoulders, which seemed covered by a film of wax, the matchless warmth and skill of her tongue, her ability to be present even in the slightest movements, made it so that the impossibility of consummating the act forced me to discover the delights of hold ing back.

The prohibition heightened our yearning. Our sessions were oblivious of time, lacking an obvious ending. Our movements stretched out endlessly and effortlessly. The act was unfulfillable, at least it was for me, and the energy traveled through my body without ever running out. In joining our bodies, we were creating an uncharted territory where past experience was no guide, and the wide field before us defied all assumptions. It was impossible to know what we’d find in it and what was expected of us.

***

*Reprinted with permission from Simone: A Novel by Eduardo Lalo, translated by David Frye, published by the University of Chicago Press. © Ediciones Corregidor, 2011. English translation © 2015 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

Eduardo Lalo has authored Los países invisibles (Editorial Tal Cual, San Juan, 2008), El deseo del lápiz: castigo, urbanismo, escritura (Editorial Tal Cual, San Juan, 2010) and Simone (Ediciones Corregidor, Buenos Aires, 2012) among other titles. He won the 2013 Rómulo Gallegos International Novel Prize.

Eduardo Lalo has authored Los países invisibles (Editorial Tal Cual, San Juan, 2008), El deseo del lápiz: castigo, urbanismo, escritura (Editorial Tal Cual, San Juan, 2010) and Simone (Ediciones Corregidor, Buenos Aires, 2012) among other titles. He won the 2013 Rómulo Gallegos International Novel Prize.

Posted: November 8, 2015 at 2:38 pm