Steal this: Jac Leirner

Fernando Castro

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

Let the true philosphers grow wild…

– FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

In 1971 Abbie Hoffman published a book that indulged my bibliomania but almost got me in serious trouble. It was titled Steal This Book. One of its premises was the subversive idea that the act of stealing a book (even that very book) was justified because the effect of possessing and circulating it engenders better people and gives the book a broader audience than if it remained out of reach on a shelf. Moreover, this act of petty thievery was part of a recipe for engaging in a sort of “guerrilla” lifestyle against the “system.” Hoffman wrote, “To steal from a brother or sister is evil. To not steal from the institutions that are the pillars of the Pig Empire is equally immoral.”

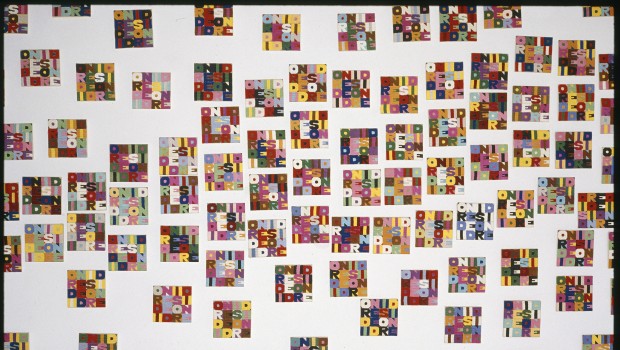

The “Pig Empire” made its presence felt in Latin America in the form of ultra-rightist coups, military interventions, predatory capitalism, corrupt governments, violation of human rights, fraudulent elections, environmental devastation, censorship, etc. As Jac Leirner turned thirty, her native Brazil was enduring one of the worse periods of hyperinflation in its modern history. As the saying goes, “money was not worth the paper in which it was printed.” Independently of Hoffman and the subversive lifestyle he endorsed, Leirner carried on her own cultural guerrilla with weapons that are reminiscent of his book but were really a legacy from Dadaism, Marcel Duchamp, and the Brazilian avant-garde. Leirner used cruzeiros, the devalued Brazilian currency, to produce an installation that addressed runaway inflation. It consisted of a string of cruzeiro bills snaking across the floor and down a flight of stairs. In her current exhibit at Sonja Roesch Gallery, a collage titled Money features devalued 100 and 100,000 cruzeiro bills painted over and mounted together to make an Albers-like square. By artistic fiat Leirner put value back into the devaluedcurrency: Money is priced at US$50,000.

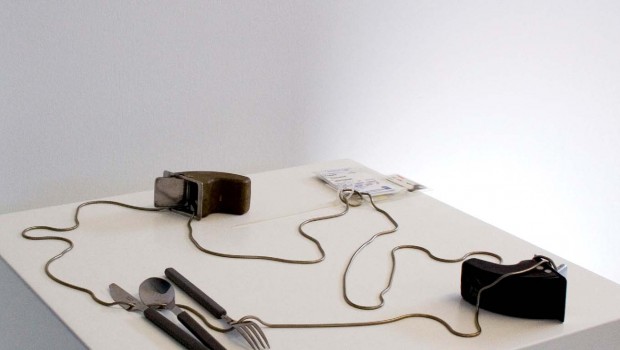

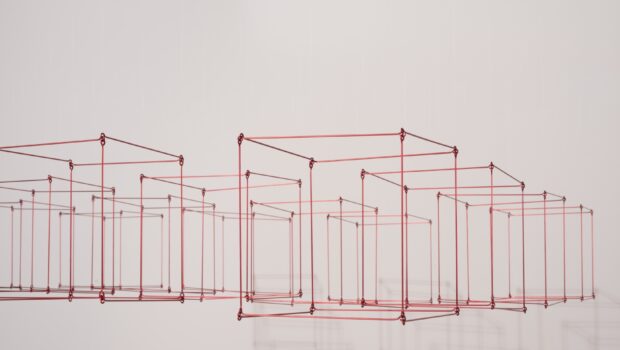

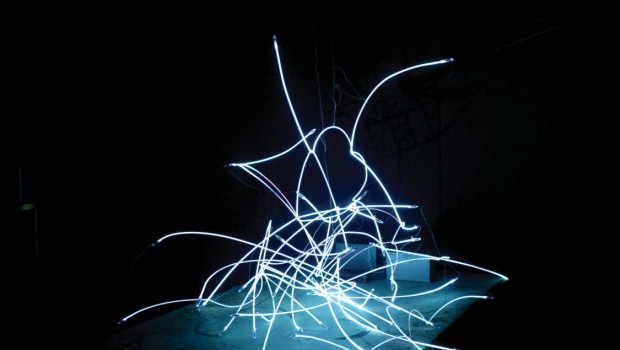

A more direct connection of Jac Leirner’s oeuvre to Hoffmann’s book comes from a series of works titled Corpus Delicti—Latin for “body of an offense” and Legalese for “collection of evidence for a crime.” There are two such works in the current exhibit and both are incongruous in different ways. The fi st one consists of airline ashtrays and silverware chained together with boarding passes as if they could be used as a necklace. “Art-to-be-worn” is an artistic genre that was explored in the sixties by Leirner’s Brazilian compatriot Helio Oiticica in works called Parangoles. One may read this unlikely piece of jewelry as a sociological comment on the widespread theft of cutlery (and blankets) as an integral part of the air travel experience. In fact, as a result of cancer prevention measures the ashtrays have almost become rare collectible items. The second Corpus Delicti is at once more aerial while also potentially weightier. It is a collection of eighteen “stolen” airsickness bags fluffed up, strung together, and hung from the ceiling as if to suggest the wake of an airplane in flight. This work is at once more poetic, international, and physiological than the first. The bags come from airlines of different nationalities. Using them implies nausea due to sickness and/or revulsion (Where have you gone, Jean-Paul?). Taking these bags is not necessarily an act of illicit appropriation but rather of partial fulfillment of their purpose: they are placed in the seat pockets to be used—as are the crossword puzzles in the travel magazines—better for art than for puking.

In her exhibit at Sonja Roesch’s Gallery, Leirner placed two such signs in opposite ends of the room, a duplicity that makes them even more invisible. —FERNADO CASTRO

It is not the first time that Leirner has collected bags that she has later used as material for a work. In 2006 she produced 144 Museum Bags. It is unlikely that Leirner stole these museum shopping bags; more than likely she got them after buying a museum souvenir. Once she spoke about her “appreciation of the commonplace” thus, “come out of the museum as garbage and go back as art.”

A work in Leirner’s exhibit germane to the title of this essay is one that explicitly addresses the possibility that someone may entertain stealing her own works. The work is often missed because it camoufl ages as part of the syntax of an art space. It is a small sign that reads, “please do not touch.”* In her exhibit at Sonja Roesch’s Gallery, Leirner placed two such signs in opposite ends of the room, a duplicity that makes them even more invisible. Of course the phrase could also be urging the guests not to fondle, but that would be an extremely un-Brazilian request.

One of the most visceral and compelling works in this exhibit is titled Lung. As many of the other works by Leirner it is Minimalist in the sense of Duchamp’s Ready- Mades: objects found by the artist and minimally altered (if at all) by her. Lung is made up of about a dozen transparent cellophane wrappers from cigarette packs (Leirner is or was a smoker). They are all stacked together on an equally transparent plastic box: lungs inside an X-rayed body. One guesses that the association of the work is with a healthy lung but somehow a smoker’s unhealthy, polluted lung becomes implicated.

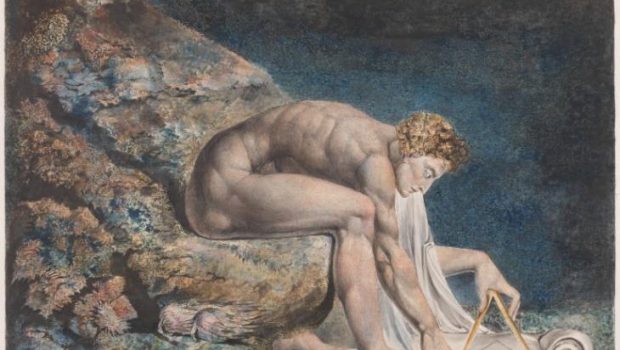

My own license for living dangerously came from Friedrich Nietzsche’s vision that society ought to foster philosophers and artists. Given its failure to do so, I reasoned, philosophers and artists ought to take matters onto their own hands and seize whatever they needed in order to pursue their lofty artistic ends. In other words, except for matters of life and death artists were not to be held accountable to the prevailing morality. Although such course of action can hardly be a prescription for a better world, many of us thought that if accused, our retort would be that our petty thefts only helped to expose— by contrast—the huge robberies of big tycoons, corporations, politicians, and governments. It would be hypocritical to accept a world where such entities stole our health, the world’s resources, our humanity and our freedom on a massive scale and condemn an artist who steals a paint brush, a book, or an ashtray. Notwithstanding this Dionysian excess, one ought to mind Immanuel Kant’s cold Apollonian dictum, “Always act according to that maxim whose universality as a law you can at the same time will.” Producing art fulfills this imperative—one can safely will a world where more and more people produce art. One cannot will a world where more and more people steal. We have more than enough thieves and artists are not notable among them.

About the Artist

Jacqueline Leirner was born in São Paulo in 1961. She studied at the Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado in São Paulo from 1979 to 1984 and taught there from 1987 to 1989. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including solo exhibitions at Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro (2002); Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (2001, 1998); Sala Mendoza, Caracas (1998); The Bohen Foundation, New York (1998); Centre d’Art Contemporain, Geneva (1993); Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC (1992), etc. Leirner’s work has been included in the Venice Biennale (1997, 1990), Documenta IX in Kassel , Germany (1992), and the São Paulo Bienal (1994, 1989, 1983). In 1991 she was a visiting fellow at University College in Oxford, England , and an artist in residence at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, England , and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota , where she had solo exhibitions. In 2001 she received a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation in New York.

Posted: April 13, 2012 at 9:45 pm