Stolen Spring, Funereal Shots

Adriana Díaz Enciso

We’d started to have glimmers of hope: spring, the vaccinations. Some warm days of luminous splendour and, of course, the blossoms: the first shy blooming cherry trees, the daffodils (riotously yellow), the saffron-giving crocus (purple, these, but nothing is as one would expect). One afternoon I spent two hours hunting for magnolia trees in my neighbourhood. There were all kinds, sizes and colours, and I decided that that was joy, more or less. I flaunted with great contentment my new identity as a genetically modified creature, the first dose of the Astra Zeneca vaccine already involved in my biology’s secret chores, and still bewildered by the knowledge that a young lady I had never seen before in my life had put inside my body those cute and lethal psychedelic spikes that adorn Covid-19, at least in photos. The lengthy winter, literally fatal for many, injurious for the mind and soul of those who survived, was coming to an end.

The visible signs of hope, however, don’t always last. After the spring début, winter came back with a vengeance. The temperature dropped, hurling us back into February; we didn’t even have a chance to put away gloves, hats and scarves, and there is no way to express our dejection because, after an endless confinement made of cold, darkness, isolation, fear, and death, many of us have no more energy or language to articulate the heaviness of the endless repetition of identical days that don’t know how to head for the future.

In my neighbourhood, the flowers’ puzzlement has been the worst of all. Last spring was benign, miraculous even; it held us at the beginning of the pandemic with blossoms everywhere and the bluest skies. This year, instead, as we approach mid-April, the splendour is hiding away. As if the first trees that bloomed had been dying away, going back in time, obeying a cruel voice that tells them, ‘not yet, not yet, perhaps never’. Some have already dropped their scant flowers without having managed to burst with joy, and the leaves start to show up. I had never seen anything like it, or sadder: those pale green leaves are telling me that this year I won’t see the treetops’ radiant clouds of white and pink. Other trees haven’t even bloomed. A few scattered buds seem to try to swell in the naked branches only to then lose their strength, and I am terrified to think that the winter’s spiteful return may not let them bloom. There are friends in other parts of London who talk about blossoms and I wonder if a spell has been cast over my neighbourhood north of the city, or whether my friends are satisfied with just a few, out of pure and honest gratitude. I’m not satisfied, and every day I go out to check on the nearest cherry and apple trees, my guardian spirits, but the blossoms aren’t there, and I soon go back home, stunned by the cold, having nowhere to go because everything is closed, my heart lethargic with sorrow. In 2021, spring has been stolen from us.

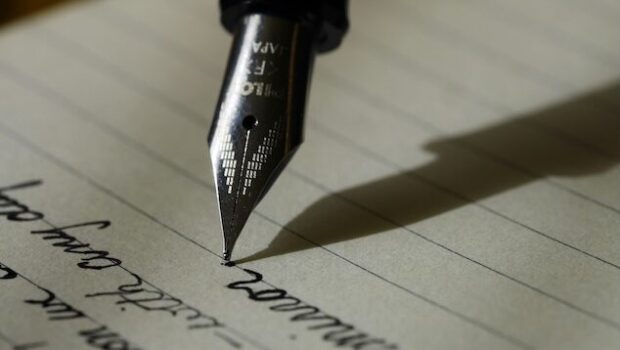

It’s true that soon (tomorrow, in fact) the shops will open again and there will be cafés, even if outdoor only, and little by little, they say, we’ll start going back to something resembling life, but this Sunday, as I write these words, I feel that such a tomorrow is a deception, just like spring; a promised gift that will never come our way.

Yesterday, I only went out to drop something in the post-box. The day was grey, cold, intolerable, and I came back home right away. At midday I started watching the news in my computer, as if guided by an alien will or, rather, by a lack of willpower. If vampires are the undead, I think that us humans, amid a pandemic, have become the unliving. Sitting in front of the screen, without knowing what to do with my day or with myself, I suddenly came across images that came and went from different cities in the UK, in other countries even, to an overcast and grey London, in particular the area around the Tower of London and Tower Bridge. The images were saturated with sadness and a solemn silence, and looked very much like that melancholic London that I dreamt of since I was little, many years before I had set foot on this city. My emotions were vague and confused. I felt an unbearable longing for London, for the city in which I thought I lived until the pandemic came and locked me up in this suburb; I felt a wild urge to be there, by the river. I also felt the sadness of the very real grey and wet London in that concrete moment, and the doubt (‘why on earth did I dream of such gloom?’); I felt the affirmation and the grievance (‘yes, I do love my city’s melancholy, but not from here, so far away’), and then the longing for all those years of my childhood and youth in which I yearned for a place that, though unknown, it was possible to reach; which was hypothetically inhabitable, and not the limbo of some neighbourhood in the north of London that doesn’t look like London and that you’re not allowed to leave.

That’s when the shots started. In the screen, I hasten to clarify. They were solemn too, spaced out minute by minute. Those doing the shooting were ‘the gunners’, members of the Royal Artillery, in full-dress uniform, and facemask. They were firing some cannons that, from the aerial views, looked like toys. The gunners that remained motionless by their cannon with one knee on the ground specially caught my attention. Still like tin soldiers, in such an uncomfortable posture. In that cold. I stayed there watching as if hypnotised, with the languor that had seized me, trying to understand from which world did those images come, the commands bellowed in the air—the most eloquent one being ‘Fire!’). 41 cannon shots. I am wholly ignorant regarding the codes of military honour or those of royalty, so the 41 struck me as an enigma, an arbitrary figure I didn’t feel like unravelling. After each shot the dense white smoke hovered for a while in the air and then dissolved over the Thames, which was as grey as the clouds, and restless.

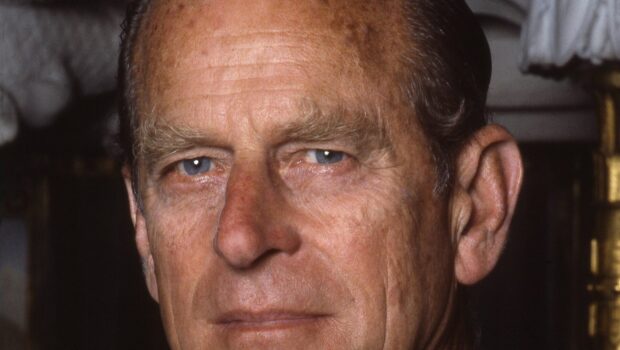

It so happens that a man had died in his sleep, a couple of months before his hundredth birthday. He was, as you surely already know, the queen’s husband. When there are royal deaths, or weddings in this country, people flood the streets in an incomprehensible manner. It was therefore odd now to hear that the Royal Family was asking people please not to leave flowers outside Buckingham Palace or Windsor Castle, or that there wouldn’t be a public funeral, not only because apparently Prince Philip didn’t like so much fuss, but because of the risk of contagion. For, of course, the pandemic touches and alters everything. Many people took no notice anyway; they went to lay flowers and to watch the cannon fire. Even 41 funereal shots are a welcome distraction in a pandemic April bent on whisking spring away.

‘The end of an era’, some say in the news. I think that no doubt this April is that. Since the pandemic started we’ve been living the end of an era, though we still don’t quite know what ended and how will what follows be. I also think that the end of that specific era the commentators are talking about will be sharper when the queen herself dies, but what I am thinking, or rather feeling, has nothing to do with what one may think about royalty, hating it or adoring it, it depends, in this or in any other country. It has to do with the simple passage of time, and with death; with the disbelief that sometimes seizes me when I realise that all eras finish, that everything comes to an end and starts again in some other way, that there is truly nothing that time leaves untouched. I do feel sorry, I can’t help it, for the elderly widow who’s lost her companion of 73 years, just as I feel sorry when I think of the millions of widows and widowers, orphans, parents who have lost their children, people who have lost siblings or friends, for whatever reason and, of course, through Covid, during these fourteen months burdened by unstoppable mourning.

Until fairly recently, when I knew of the death of someone I loved, I lived it as a tragedy. The pandemic has come to give me a lesson that I’m not sure I wish to learn, but I have no choice: death is, indeed, a tragedy for those who love someone who dies, but it is also simply what we humans do. All of us. That’s what I think as I see the repetition of cannon shots saluting someone I didn’t know, all identical but not the same, just like the pandemic days; the cannon fire in central London, which I look at and feel like crying, longing to walk those streets again, to verify that the city is still there, because the strange ceremony the news is showing, even if it says “live”, seems to be something quite remote, even from another time. If it were not for the facemasks.

***

That was yesterday. Today, after lunch, I thought that I didn’t want to spend the Sunday afternoon locked up thinking of how we all die. The idea of going out, though, made me anxious too. Going where? To one of the two same parks, to my neighbourhood’s streets that I’ve been seeing ad nauseam? In the cold, going round and round the same places? I decided to venture a bit further and go and find a new park. To get there I had to walk past the New Southgate cemetery. It’s enormous, one of the huge cemeteries built in the outskirts of London in the 19th Century, and its entrance and chapel are picturesque enough. The long walk alongside its railing kept on talking to me of the omnipresence of death. The cold was intense; I had to put on my gloves, and though I was following the instructions in the map, I couldn’t find the park. Disappointed, I was about to go back home when I saw some greenery at the end of one street. There was a park there, though I don’t think it was the one I was looking for. Far in the distance was the children’s playground, its colours standing out against a backdrop of hawthorn trees in bloom. They were the only thing I’d seen during my journey affirming the presence of spring; in the streets I had only found those ghostly hints of flowers in bare trees that I’ve already described. I decided to reach the hawthorns until the end of my walk, to crown perseverance—though I don’t know if mine or that of springtime, feeble but tenacious.

I turned towards the park’s wilder area. Two small football grounds on a narrow strip of grass adjoined masses of trees and grown grass. There was pretty little green on the treetops, but further round a bend I could glimpse another hawthorn, and that’s where I headed for, almost happy. Just then I saw on the ground a pigeon’s tattered carcass. Must have been a fox, perhaps.

I wanted to believe that behind the copse there was a mystery, another world, though I knew too well that all there was were the rather dull houses in the streets I had come by. The sky still had brushstrokes of grey clouds, but now and then it opened to let some mirage of sunshine through, as if darkness and light were fighting a dogged battle for the dominion of that theatre of suburban life. Raindrops started falling, rather fine, invisible, like pinpricks on my face. A couple of optimists who were air-bathing (since sunbathing wasn’t possible) by one of the football grounds got up and left. I walked across the grass to get closer to the hawthorn trees, and to avoid seeing the dead pigeon again. There was a man running to-and-fro just by my goal, without straying too far, and I thought that perhaps for him as well those flowers were a kind of talisman. When I got closer I realised that he didn’t want to walk far from his son’s pram.

I reached the humble white clouds of blossoming hawthorn when the man was putting on his jacket and was joined by a little girl. He took her hand, pushed the pram and the three of them walked away, rather happily. The hawthorn petals, minute, had started to cover the ground, and along with the echo of the few children still laughing in the playground at my back, they cheered me up. They looked like confetti, the promise of some party. They could have been snow too, hadn’t their contour been so neat.

I started to walk back, not knowing if that park was the one I had been looking for, and not wishing to find out in the map, happy with not knowing where I had been during that recess of time cut into that grey Sunday.

Perhaps, I told myself, heartened by those glimpses of life that the afternoon had granted me, we will still have some spring. Perhaps tomorrow will indeed come, and the outdoor cafés will open, even if not yet inside, and we will indeed be able to sit down and have a coffee like people who live and dream, even if we shake with cold.

Soon the rain stopped. The sun had come out by the time I got home.

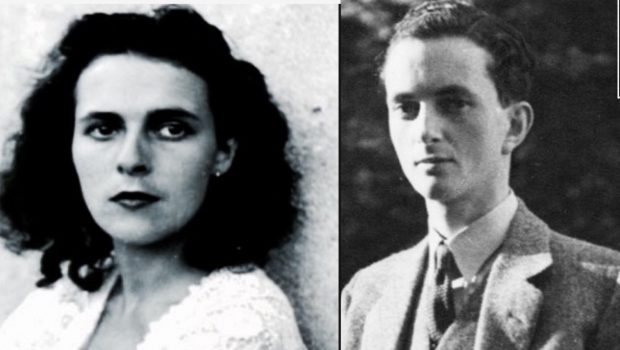

*Image by Allan Warren

Se empezaban a entrever resquicios de esperanza: la primavera, las vacunas. Algunos días cálidos, de luminoso esplendor y, desde luego, las flores: los primeros, tímidos cerezos en flor, los narcisos (de un amarillo impúdico), los bulbos de azafrán (estos morados, pero es que nada es como uno espera). Una tarde pasé dos horas a la caza de magnolias por mi barrio. Había de todo tipo, tamaños y colores, y decidí que eso era más o menos la alegría. Paseaba con gran contento mi nueva identidad de criatura genéticamente modificada, con la primera dosis de la vacuna Astra Zeneca ya involucrada en los quehaceres secretos de mi biología, aún azorada de saber que una señorita a la que no había visto nunca en mi vida me puso en el cuerpo esos monísimos y letales piquitos psicodélicos que adornan al Covid 19, al menos en las fotos. Se acababa el invierno, larguísimo, literalmente mortal para muchos, injurioso para el alma y la mente de los que sobrevivimos.

Pero los signos visibles de la esperanza no siempre son duraderos. Tras el estreno primaveral, el invierno volvió con saña. Bajó la temperatura, lanzándonos de golpe otra vez a febrero; no alcanzamos siquiera a guardar guantes, gorros y bufandas, y no hay forma de expresar el desaliento porque, tras un encierro interminable de frío, oscuridad, aislamiento, temor y muerte, a muchos ya no nos quedan energía ni lenguaje para articular la pesadez de la repetición sin fin de días iguales que no saben dirigirse al futuro.

En mi barrio, lo peor ha sido el desconcierto de las flores. La primavera pasada fue benévola, milagrosa incluso; nos sostuvo al inicio de la pandemia con flores por todas partes y cielos azulísimos. Este año, en cambio, ya acercándonos a mediados de abril, el esplendor se oculta. Como si los primeros árboles que florecieron se hubieran ido apagando, regresando en el tiempo, obedeciendo a una voz cruel que les dice “aún no, aún no, quizá jamás”. Algunos ya dejaron caer sus pocas flores sin haber llegado al estallido de su gozo, y empiezan a salir las hojas. Nunca había visto cosa igual, ni más triste: esas hojas de un verde pálido me dicen que este año no veré las nubes radiantes rosas y blancas de sus frondas. Otros árboles no han floreado siquiera. Unos cuantos botones parecen querer hincharse en las ramas desnudas y perder luego su fuerza, y tengo terror de que el avieso regreso del invierno no les permita florecer. Hay amigos en otras partes de Londres que hablan de flores y me pregunto si ha caído un hechizo sobre mi barrio al norte de la ciudad, o si mis amigos se conforman con unas cuantas por pura, honesta gratitud. Yo no me conformo, y todos los días salgo a inspeccionar los cerezos y manzanos más cercanos, mis seres tutelares, pero las flores no están ahí, y regreso pronto a casa, aturdida por el frío, sin tener a donde ir porque todo está cerrado, con el corazón aletargado de pesar. En 2021, nos han robado la primavera.

Es cierto que ya pronto (mañana, de hecho) abrirán las tiendas y habrá cafés, aunque sea solo al aire libre, y poco a poco, dicen, iremos regresando a algo parecido a la vida, pero el domingo en que escribo estas palabras siento que ese mañana, como la primavera, es un engaño, un regalo prometido que no llegará nunca.

Ayer solo salí a echar una carta en el buzón. El día era gris, frío, intolerable, y volví a casa de inmediato. Al mediodía me puse a ver las noticias en la computadora, como gobernada por una voluntad ajena, o más bien, por una no-voluntad. Si los vampiros son los no-muertos, los humanos a media pandemia, pienso, nos hemos convertido en los no-vivos. Sentada frente a la pantalla, sin saber qué hacer con mi día, conmigo misma, de pronto me encontré con imágenes que iban y venían de diversas ciudades del Reino Unido, de otros países incluso, a un Londres nublado y gris, en particular el área alrededor de la Torre de Londres y Tower Bridge. Eran imágenes saturadas de tristeza, de un solemne silencio, muy parecidas a ese Londres melancólico con el que yo soñaba desde niña, desde muchos años antes de haber puesto un pie en esta ciudad. Mis emociones eran desvaídas y confusas. Sentía una nostalgia insoportable de Londres, de la ciudad en la que creía vivir hasta que llegó la pandemia y me encerró en este suburbio; unas ganas locas de andar ahí, junto al río. Sentí también la tristeza del muy real Londres gris y húmedo en ese concreto instante, la duda (“¿pero por qué soñaba yo con semejante pesadumbre?”); la afirmación y la queja (“sí, amo esa melancolía de mi ciudad, pero no desde acá, tan lejos”), y luego la nostalgia de todos esos años de infancia y juventud en que añoraba un lugar desconocido al que era posible sin embargo llegar, que se podía, hipotéticamente, habitar, que no era el limbo de un barrio al norte de Londres que no parece Londres y del que no puedes salir.

Entonces empezaron los disparos. En la pantalla, me apresuro a aclarar. Solemnes también, espaciados minuto a minuto. Los que disparaban eran miembros del Cuerpo de Artillería Real, vestidos de gala y con cubrebocas. Disparaban unos cañones que, desde las vistas aéreas, parecían de juguete. Me llamaron especialmente la atención unos que se mantenían inmóviles cerca de su cañón con una rodilla al suelo. Quietos como soldaditos de plomo, en esa postura tan incómoda. En ese frío. Me quedé mirando como hipnotizada, en esa languidez que se había apoderado de mí, tratando de entender de qué mundo me llegaban esas imágenes, los gritos al aire dando órdenes (la más elocuente era “Fire!”). 41 cañonazos. Desconozco los códigos del honor militar o de la realeza, así que el 41 me pareció un enigma, una cifra arbitraria que no tuve ganas de desentrañar. Tras cada disparo el denso humo blanco quedaba suspendido un rato en el aire y luego se dispersaba sobre un Támesis tan gris como las nubes, agitado.

Sucede que había muerto un hombre, dormido, a unos meses de cumplir los cien años. Era, como ya sabrán, el esposo de la reina. En este país, cuando hay muertes o bodas reales, la gente se desborda incomprensiblemente en las calles. Era extraño ahora escuchar que la realeza pedía que por favor no dejaran flores afuera del Palacio de Buckingham o el Castillo de Windsor; o que el funeral no sería público, no nada más porque al príncipe Felipe al parecer no le gustaba tanta alharaca, sino por el riesgo de contagio. La pandemia, claro, todo lo toca, todo lo altera. Mucha gente no hizo caso de todas formas; fueron a dejar flores y a ver los cañonazos. Hasta 41 disparos fúnebres son una bienvenida distracción en un abril de pandemia que nos escamotea la primavera.

“El fin de una era”, dicen algunos en las noticias. Yo pienso que sin duda este abril lo es. Desde que empezó la pandemia estamos viviendo el fin de una era, aunque no sepamos muy bien todavía qué se acabó y cómo será lo que sigue. Pienso también que más nítido será el fin de esa era específica de la que hablan los comentaristas cuando la reina muera también, pero lo que estoy pensando, o más bien sintiendo, no tiene nada que ver con lo que uno pueda pensar sobre la realeza, odiándola o adorándola, según, en este ni en ningún otro país. Tiene que ver con el simple paso del tiempo, y con la muerte; con esa incredulidad que me atenaza de pronto cuando me doy cuenta de que todas las eras terminan, de que todo llega a su fin y recomienza de otra forma, de que el tiempo de verdad no deja nada intacto. Sí me da pena, ni modo, pensar en la viuda anciana que perdió a su compañero de 73 años, como me da pena pensar en los millones de viudas y viudos, huérfanos, padres que han perdido a sus hijos, gente que ha perdido hermanos, amigos, por la causa que sea y, claro, por el Covid, durante estos catorce meses cargados de luto imparable.

Hasta hace muy poco, al enterarme de la muerte de alguien querido, lo vivía como una tragedia. La pandemia ha venido a darme una lección que no sé si quiero aprender, pero no tengo alternativa: la muerte es, sí, una tragedia para los que queremos a quien se va, pero es también, simplemente, lo que los humanos hacemos. Todos. Eso pienso mientras veo la repetición de cañonazos en honor alguien a quien no conocí, idénticos pero no los mismos, como los días de la pandemia; los cañonazos en el centro de Londres que miro con ganas de llorar por la nostalgia, por las ganas de volver a andar en esas calles, de corroborar que la ciudad sigue ahí, porque esta extraña ceremonia que están pasando en las noticias, aunque diga “en vivo”, parece algo muy lejano y hasta de otro tiempo. Si no fuera por los cubrebocas.

***

Eso fue ayer. Hoy, después de comer, pensé que no quería pasar la tarde del domingo encerrada pensando en cómo todos nos morimos. La idea de salir me daba angustia también. ¿A dónde? ¿A los dos parques de todos los días, a las calles de mi barrio ya vistas hasta el cansancio? ¿En el frío, dando vueltas y vueltas por los mismos lugares? Decidí aventurarme un poco más lejos e ir a encontrar un parque nuevo. Para llegar tenía que pasar frente al cementerio de New Southgate. Es enorme, uno de los grandes panteones construidos en los alrededores de Londres en el siglo XIX, y su entrada y capilla son suficientemente pintorescos. La larga caminata tras sus rejas seguía hablando de la omnipresencia de la muerte. El frío era intenso; me tuve que poner los guantes, y aunque seguía las instrucciones del mapa, no lograba encontrar el parque. Decepcionada, estaba a punto de volver a casa cuando vi al fondo de una calle algo de verdor. Había un parque ahí, aunque no creo que fuera el que andaba buscando. A lo lejos estaban los juegos de los niños, los colores resaltando contra el blanco de una serie de árboles de espino en flor. Eran lo único que había visto en todo el camino que afirmara la presencia de la primavera; en las calles solo había esos barruntos fantasmales de flores en árboles desnudos que ya he descrito. Decidí acercarme a ellos hasta el final, para cerrar mi paseo coronando la perseverancia, no sé si mía o de la primavera en sí, endeble pero tenaz.

Me desvié hacia la parte más agreste del parque. Dos canchas pequeñas de futbol en una franja estrecha de hierba colindaban con un montón de árboles y hierba crecida. Había muy poco verde en las frondas, pero a lo lejos, tras una curva, asomaba otro espino y hacia allá me dirigí, casi alegre. Justo entonces vi en la tierra el cadáver destrozado de una paloma. Habrá sido una zorra.

Quise creer que tras el bosquecillo había un misterio, otro mundo, aunque bien supiera que solo había las casas más bien anodinas de las calles por las que había llegado. El cielo seguía atravesado de nubes grises, pero de repente se abría para dejar pasar espejismos de sol, como si la oscuridad y la luz estuvieran librando una porfiada batalla por el dominio de ese teatro de vida suburbana. Empezaron a caer unas gotas de lluvia, finísimas, invisibles, como alfileres en la cara. Unos optimistas que estaban tomando el aire (ya que no el sol) junto a la portería de una de las canchas se levantaron y se fueron. Yo crucé la hierba para acercarme a los espinos, y para no volver a ver a la paloma muerta. Había un hombre que corría de un lado a otro junto a mi meta, sin alejarse demasiado, y pensé que quizá para él también esas flores eran una especie de amuleto. Cuando estuve más cerca me di cuenta de que no quería alejarse de la carriola de su hijo.

Llegué junto a las humildes nubes blancas de espinos en flor cuando el hombre se ponía la chamarra y era alcanzado por una niña pequeña, a la que tomaba de la mano. Luego, guiando la carriola, se fueron los tres muy contentos. Los pétalos de los espinos, diminutos, habían empezado a cubrir la hierba y, con el eco de los gritos de los pocos niños que seguían en el área de juegos a mi espalda, me alegraron. Eran como confeti, una promesa de fiesta. Podrían haber sido nieve, también, si sus contornos no hubieran sido tan perfectos.

Emprendí el regreso sin saber si ese parque era el que buscaba y sin querer averiguarlo en el mapa, contenta con no saber dónde había estado durante ese hueco de tiempo abierto en el domingo gris.

Quizá, me dije, alentada por esos vislumbres de vida que me había dado la tarde, tendremos todavía algo de primavera. Quizá sí llegará mañana, y abrirán los cafés al aire libre, aunque adentro todavía no, y sí podremos sentarnos a tomar un café como gente que vive y sueña, aunque temblemos de frío.

Pronto paró la lluvia. Para cuando llegué a casa, había salido el sol.

Adriana Díaz-Enciso es poeta, narradora y traductora. Ha publicado las novelas La sed, Puente del cielo, Odio y Ciudad doliente de Dios, inspirada en los Poemas proféticos de William Blake; los libros de relatos Cuentos de fantasmas y otras mentiras y Con tu corazón y otros cuentos, y seis libros de poesía. Su más reciente publicación, Flint (una elegía y diario de sueños, escrita en inglés) puede encontrarse aquí.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.